Post researched and written by Kari Wilson-Allan, Collections Assistant – Archives

As we sit in the midst of a global pandemic, doing our best to meet public health requirements while awaiting that crucial vaccine, it seems timely to take a retrospective look. Anyone who has spent time on social media in the last few years will be aware that vaccination is a contentious subject – but has this always been the case? Hocken holdings illuminate the story particularly strongly in the first decade of the twentieth century, and bring human elements to the mix.

Edward Jenner’s successful 1796 inoculation of a patient with cowpox (thereby granting them immunity to smallpox) laid the Western foundation for vaccination, although a number of Eastern societies had already made progress with immunology.[i]

New Zealand law required vaccination against smallpox of Pākehā infants from 1863, though adherence to the rule was limited for many years.[ii] In the era I’m investigating, vaccines were administered by scraping back a patch of skin, and applying glycerinated calf lymph to the wound.

An illustration from C.W. Dixon’s ‘Smallpox’ (J. & A. Churchill, London, 1962, p.291) showing the progression of the vaccine on the body. Dixon had previously been Professor of Preventive and Social Medicine at the University of Otago.

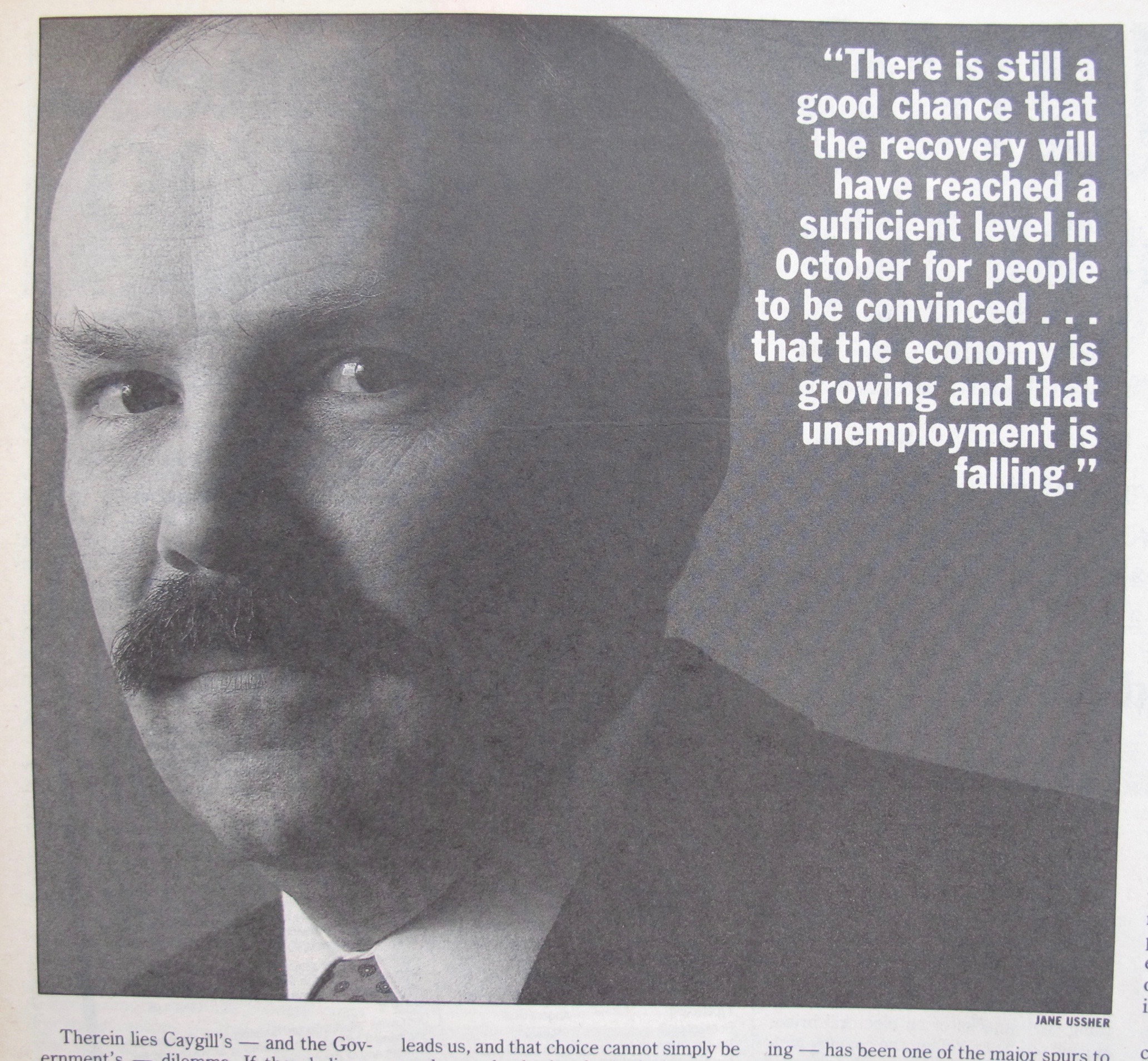

While, according to the statistics, many children escaped the attention of the Vaccination Inspector, thirteen-month-old Rera Mary Taylor did not. Her father, Dunedin butcher William D. Taylor, received a notice from the Inspector’s Office in March 1904. Whether her elder sister Nina had earlier received her prophylaxis is unknown.

Taylor complied with the order, giving permission for Rera’s vaccination. Had he not, he would have been at risk of a fine not exceeding forty shillings, the equivalent of $366 today, and his ‘failure to take advantage of the means provided by the Government for gratuitous vaccination [would be] a menace to the general safety’. [iii]

Notice to William D. Taylor from the Vaccination Inspector’s Office requiring the vaccination against smallpox of his daughter Rera Mary Taylor (1904), MS-1633/036. Curious eyes might wonder at the mention of the ‘s.s. “Gracchus”’ included in the demand. We will return to this.

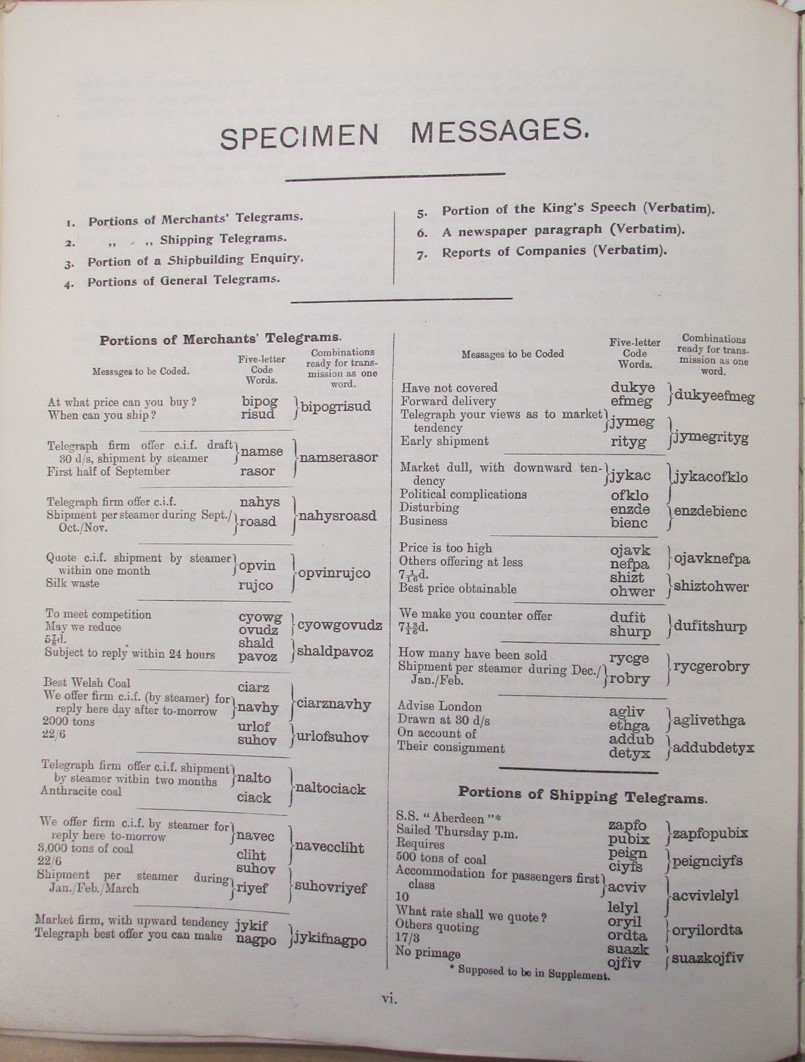

While Taylor complied with his obligations, Alexander Miller, an orchardist of East Taieri, proactively bypassed them. In 1906, he applied for – and received – a certificate for exemption from vaccination under the terms of the Public Health Act, 1900, part IV for his daughter, Margaret Winnifred, at the time a baby of one month and nineteen days. Miller had convinced the authorities that he was ‘conscientiously of the opinion that vaccination would be prejudicial’ to the infant. Why he took this stance is unknown to us, but the document exempted him from all liability for any consequences of non-vaccination.

Kidd, Margaret Winnifred : Certificate for exemption from vaccination (1900, 28 November 1906), Misc-MS-0727

In 1900, just over sixteen percent of Pākehā[iv] children born that year were successfully vaccinated.[v] However, a notable jump in the rates occurred in the year 1903, before falling again to under eight percent in 1906, the year Margaret Miller was born. [vi] What happened in 1903 to cause one in four infants to receive the vaccine?[vii]

In May of that year, the Steamer Gracchus came from Calcutta via other ports to Dunedin and finally Lyttelton, with smallpox cases on board. This resulted in several deaths, one of which counts in New Zealand’s statistics as the death occurred at Lyttelton. Bell, the third engineer, had a critical case; the Evening Star recorded that there was no room to place a threepenny piece between the pustules [and] the eyes are nearly closed’.[viii]

Contact tracing was established, and a number of the wharf labourers chose not to have the vaccine, despite the offer of three days paid leave to allow for incapacitation for sore arms. They were instead placed in quarantine. In Dunedin, a woman who had been a passenger aboard the ship also contracted smallpox and passed it to her housemate. Both survived.

The documents pictured above prove that vaccination was clearly part of the public health infrastructure. Yet, as we’re seeing today, public health measures are not universally agreed with. Edwin Cox was one vehement opponent at the century’s turn.

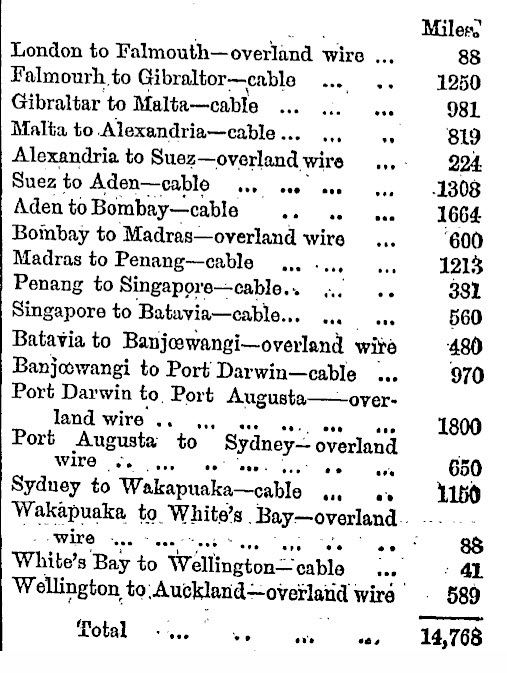

An English migrant, Cox was a dentist and president of the Anti-compulsory Vaccination League of New Zealand. Hocken holds two of his publications, as well as a number of his diaries and extensive autobiographical papers.

In the first pamphlet, dated 1904, The vaccination coup d’etat in New Zealand whereby a mercenary imposture usurped the throne of right, he expounds his theory that vaccinations are essentially a self-justifying make-work scheme. Because, he argues, the Public Health Act requires compulsion, and pushes out ‘pro-vaccinist literature, diagrams and statistics, with disgusting photographs’, and led to the appointment of Health Officers and the construction of lymph factories, all these entities have a ‘vested interest’ to keep the threat of smallpox in the public eye and justify their existence. He suggests they are ‘a Fire Brigade roused by cry of fire’. He asks ‘What if vaccination is not, and never was, a protective against smallpox? What if it is, and never has been anything else, than a “delusion and a snare?”’

Cox’s ‘Vaccination coup d’etat’, 1904

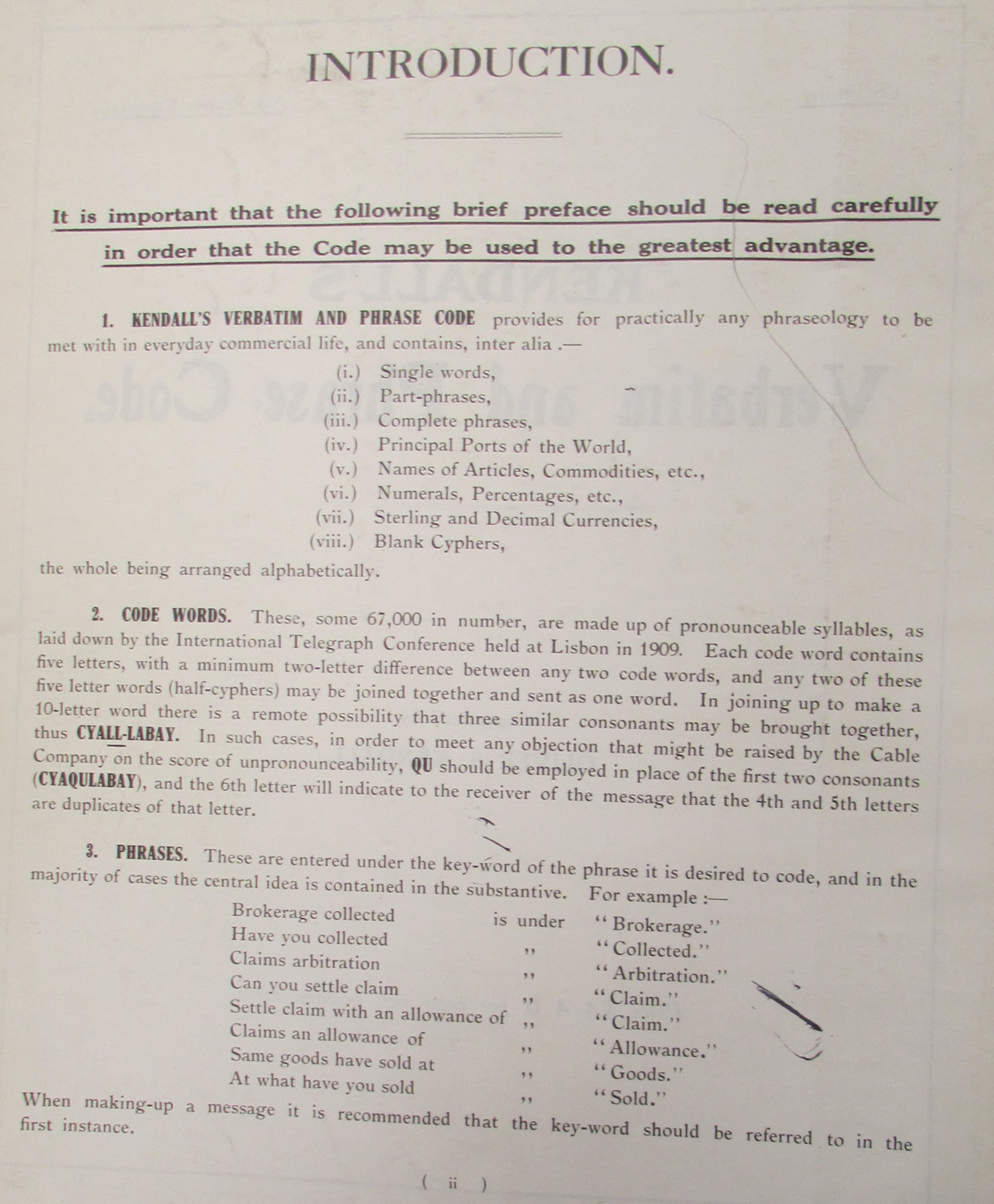

In his more substantial Protest of an anti-vaccinist (1905), we get a better sense of his objection to vaccines. This small volume is a collection of articles and letters he has written and lectures given in New Zealand and England.

Within the pages, he describes how, as a young man, he ‘offered up his arm’ for a new method of vaccination. He then records his ‘months of pain and trouble’ that ensued. He describes how, after twenty-four hours, his arms and trunk were so swollen that his clothing needed to be cut off, as ‘foul diseases, as by conspiracy, like a gang of midnight burglars, went ravaging every organ, poisoning all they touched!’ He continues his report, hopefully hyperbolically, stating that ‘fever, jaundice, stomatitis, racking headache, and insomnia’ were ‘the leaders in this desperate assault’ [and that] ‘for some days as [he was] ill as a man could be’. All this took him to bed for ten days, but he felt he should have rested longer, the ‘filthy Jennerian rite’ also having caused ‘noisome abscesses’. While he ultimately recovered, he declared ‘I believe nothing could have brought me through this horrible complication of maladies but my good constitution, temperate habits, and the devoted nursing of my wife’. Ultimately, his experience was ‘object-lesson’ in vaccination.[ix]

Cox’s ‘Protest’, 1905

While condemning vaccination as a ‘grotesque superstition’ of the medical profession, he rails against compulsion. [x] His three arguments follow. The first was that ‘vaccination is no protection whatever against small-pox’[xi], the second, that it ‘does not mitigate small-pox’[xii] (not so, according to the Chief Health Officer as reported in the Evening Star[xiii]), and finally, no doubt based on his personal experience, ‘that it is a prolific cause or vehicle of other disease’.[xiv]

His general belief is that sanitation is the solution to everything, and calls smallpox the ‘beggar’s disease’. [xv] He wants smallpox hospitals built, tenements torn down, disinfection and notification, and appeals to public responsibility in order to avoid ‘the odious and cruel ordeal of inoculation’ and to counter the vested state interests mentioned in his earlier pamphlet.[xvi]

While smallpox didn’t take off in 1903, an epidemic did spread through Northland in 1913. The 2000 infected were predominantly Māori, and all 55 who died were.[xvii] Many measures familiar to us today were put in place, and poor living conditions and sanitation in Māori communities were widely blamed in Pākehā newspapers. This, despite Māori being more willing to receive vaccination than Pākehā when it was made widely available in the area.[xviii]

These items highlight the diversity of opinion that is familiar to us today, even if expressed in a different manner.

You may wonder, finally, what became of Rera and Margaret.

Rera, born in 1902, was one of four apparent siblings. Despite her and her sister having reo Māori names, I have not yet identified anything further to suggest they may have been Māori. She and her siblings do not appear in our database of local schools, nor do the family appear in Stones or other directories. Rera and her family appear to have moved to Hamilton eventually, and she later married Harold Edwin Marten. She died in 1988, aged 85 years.

Margaret attended East Taieri School, going on to take a free evening place at the Technical College, studying dressmaking and millinery. She later married George Wilfred Kidd, and died in 1987.

So each woman lived into her eighties, one vaccinated, the other presumably not. We can only guess at their personal opinions of vaccines and how they addressed the issue with their own children.

[i] https://www.immune.org.nz/vaccines/vaccine-development/brief-history-vaccination accessed 21 July 2020

[ii] This was the only vaccine available at the time

[iii] https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/monetary-policy/inflation-calculator accessed 20 August 2020

[iv] Children born to Māori parents were not included in the statistics, nor were their births registered at this time

[v] New Zealand Official Year-Book, 1901, p.302

[vi] Ibid., 1907, p.468

[vii] Ibid., 1904, p.285

[viii] Evening Star, 3 September 1902, p.4

[ix] Protest of an anti-vaccinist, p.9

[x] Ibid., p.14

[xi] Ibid., p.12

[xii] Ibid., p.15

[xiii] Evening Star, 3 September 1902, p.4

[xiv] Protest of an anti-vaccinist, p.16

[xv] Ibid., p.45

[xvi] Ibid., p.67

[xvii] https://teara.govt.nz/en/epidemics/page-4 accessed 24 July 2020