Blog post researched and written by Kari Wilson-Allan, Collections Assistant – Archives

Content warning: this blog post includes quotes of homophobic statements. Reader discretion is advised. It is also acknowledged that there are a multitude of gay communities, and other communities situated around sexuality and gender. However, during the era discussed in this post, the narrower term ‘gay community’ was used.

As we traverse the current pandemic, many of us have both a heightened sense of vulnerability and a growing awareness of how the media can influence chains of events. Looking to the HIV/AIDS (Human Immunodeficiency Virus/ Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) epidemic, still ongoing, we can see these same factors at play.

This post explores how the contents of one selected publication – Pink Triangle – contrasted with the messaging in mainstream media, represented here by the Otago Daily Times (henceforth ODT). Pink Triangle was a lesbian and gay community newspaper, published in Aotearoa by the New Zealand National Gay Rights Coalition (NGRC) from 1979 through to 1990; the NGRC itself having come together in 1977 as calls for gay liberation and homosexual law reform grew (decriminalisation of homosexuality was attained in 1986). Who did the NGRC want to reach? Content and advertising found within Pink Triangle indicates that their likely audience was predominantly financially comfortable, cisgender[i], gay, lesbian and bisexual Pākehā adults.

In reading Pink Triangle, we can hear the voices obscured from the dominant narrative. Understandably, with the legal situation and strong societal prejudice, very few felt safe to ‘out’ themselves to the established press, or even trust the information supplied, but Pink Triangle met some of these needs. What follows is predominantly an exploration of material published in Pink Triangle (contrasted with material published in the ODT), between mid-1981 through to early 1985, looking at the emerging discourse around AIDS in the gay community.

Several themes quickly become apparent: along with a conviction that AIDS should not be portrayed as an illness only affecting homosexual people, issues around blood donation, community support, the need to counter misinformation, the continued presence of medical homophobia, how the situation might affect calls for law reform, and, finally, how the gay community was portrayed in the media were all significant points for discussion.

As we now know, HIV can result in AIDS. However, as the first cases of AIDS were identified among gay men in the United States, little was known about its causes and consequences. Some mainstream media adopted the pejorative term GRID: Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, which could only compound homophobic sentiment. Due to the variation of early terms used, finding relevant article references in databases proved challenging.

The first mention of anything relating to HIV or AIDS I uncovered in Pink Triangle was a snippet entitled ‘Gay pneumonia? Not really, says researcher’ in September 1981.[ii] (One of the first American reports was published in the New York Times in July of that year, describing a ‘rare cancer’). The USA Centres for Disease Control and Prevention coined the term AIDS the following year.

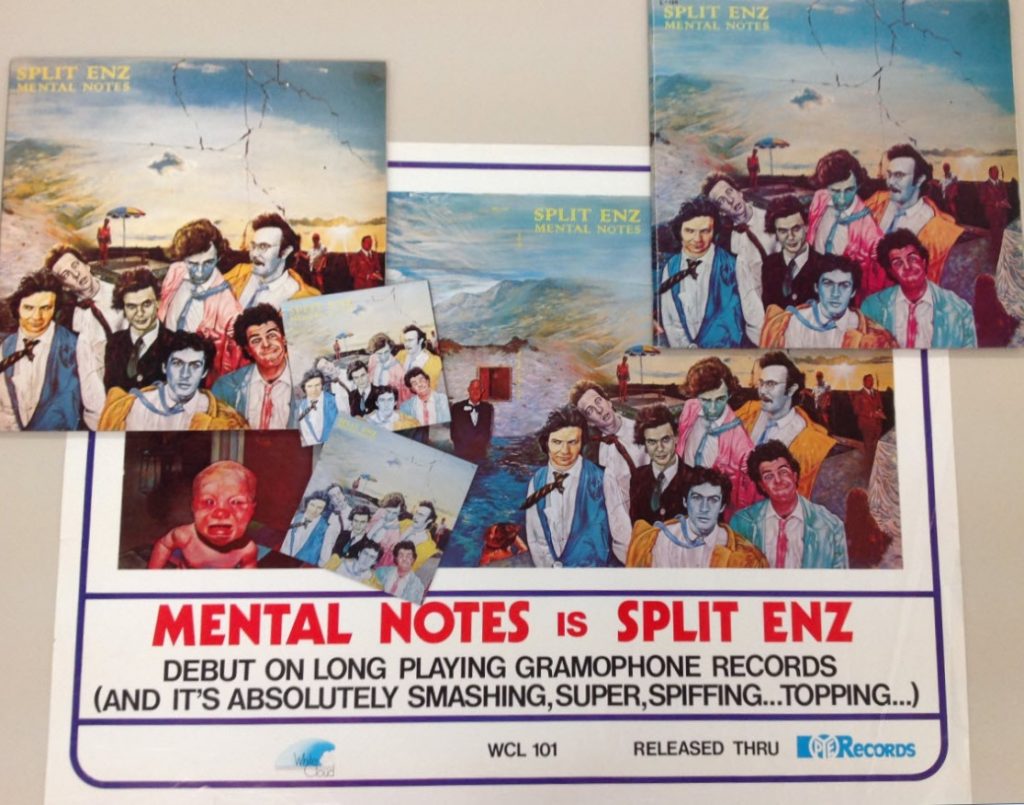

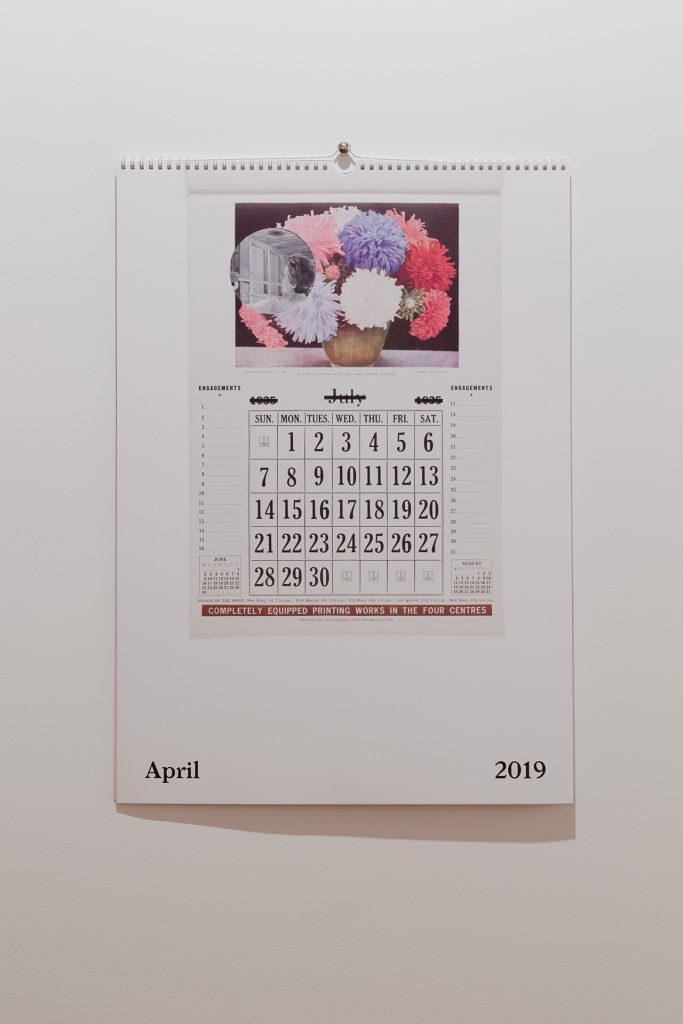

‘Hets miss out on gay blood’, Pink Triangle, May June 1983, p.1

One of the first areas of discussion in Pink Triangle revolved around blood donations. While the ODT printed an article in May 1983 titled ‘Some homosexuals’ blood unacceptable’[iii] Pink Triangle were simultaneously proclaiming ‘Hets [heterosexuals] miss out on gay blood’.[iv] As testing was not yet available, and the potential for transmission via blood transfusion was unknown, ‘promiscuous homosexuals and intravenous drug addicts’ (groups considered at high risk of carrying the later-named HIV), were requested not to donate their blood to the Wellington blood transfusion service. The wider discourse around blood donation from the medical establishment was lambasted as homophobic by the gay community, and a number of protest actions occurred, including regular donors from the community returning their donor cards, and, controversially, calls from one gay activist to continue donations regardless.[v] Later that year, the doctor who front-footed the policy, when asked about its success, made the arguably peculiar comment that ‘people in Wellington are co-operating and not engaging in blackmail’.[vi]

‘Gays co-operate’, Pink Triangle, Issue 44, July-September 1983, p.3

When, in 1984, a test became available to indicate exposure to HIV, Bruce Burnett, head of the New Zealand AIDS Support Network – following an American precedent – encouraged the community to avoid it. He was concerned that a possible lack of privacy around test results could be ‘used to discriminate against and label gay men’.[vii] He preferred the test only be used for screening purposes prior to blood donation, and not an opportunity the gay community should take up out of curiosity, with the hope that:

AIDS is no longer seen as a ‘gay’ disease, at least not by most medical people. Our sexuality is no longer seen as a cause, merely as one mode of transmission among others such as heterosexual intercourse, transfusions and IV [intravenous] drug use.[viii]

As Pink Triangle articles traced the movement of the virus closer and closer to Aotearoa New Zealand, by the summer of 1982-83,[ix] they began directing attention to the myriad damaging implications of AIDS being referred to as a ‘gay plague’, imploring the gay community to work together to ensure its collective health. Concerns were expressed that while homosexual communities were having success in establishing their identity separate from the pathologising tendencies of the medical world, now was a time where that profession could once again very easily slip into a position of power and control:

We have to make illness gay and dying gay, just as we have made sex and baseball and drinking and eating and dressing gay. This is the challenge to us in 1982 – just when the doctors are trying to do it for us…[x]

The NGRC struck out at straight media for spreading misinformation about AIDS: implications that the gay community was the only group at risk were rife. This focus on the ‘gay disease’ further stigmatised the community and emboldened homophobic options and actions.[xi] By 1984, the aforementioned AIDS Support Network was established, and advertisements began to appear in Pink Triangle.[xii] Their stated aims were to:

prevent a major outbreak of AIDS and ARC [AIDS-Related Complex] in NZ through education, the promotion of risk-reduction measures and the training of cousellors [sic] and support personnel.

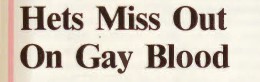

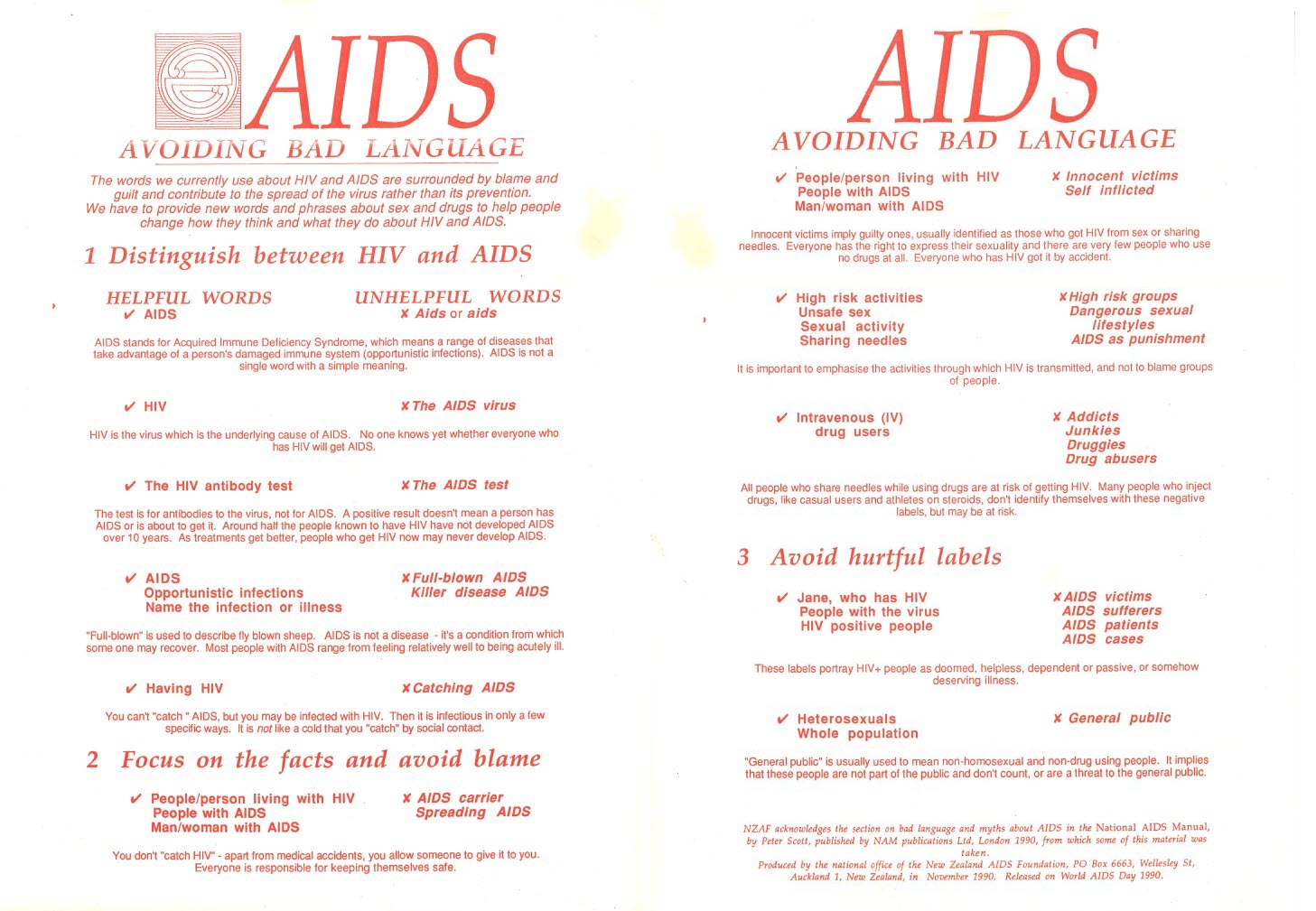

The AIDS Support Network would later become known as the New Zealand AIDS Foundation, and its work changed the AIDS and HIV landscape immeasurably. Some examples of their work to minimise stigma in particular are pictured below.

Flyer from the New Zealand AIDS Foundation on ways to reduce stigmatising language.

Avoiding bad language. New Zealand AIDS Foundation, Auckland, 1990. Ephemera Collection, Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago.

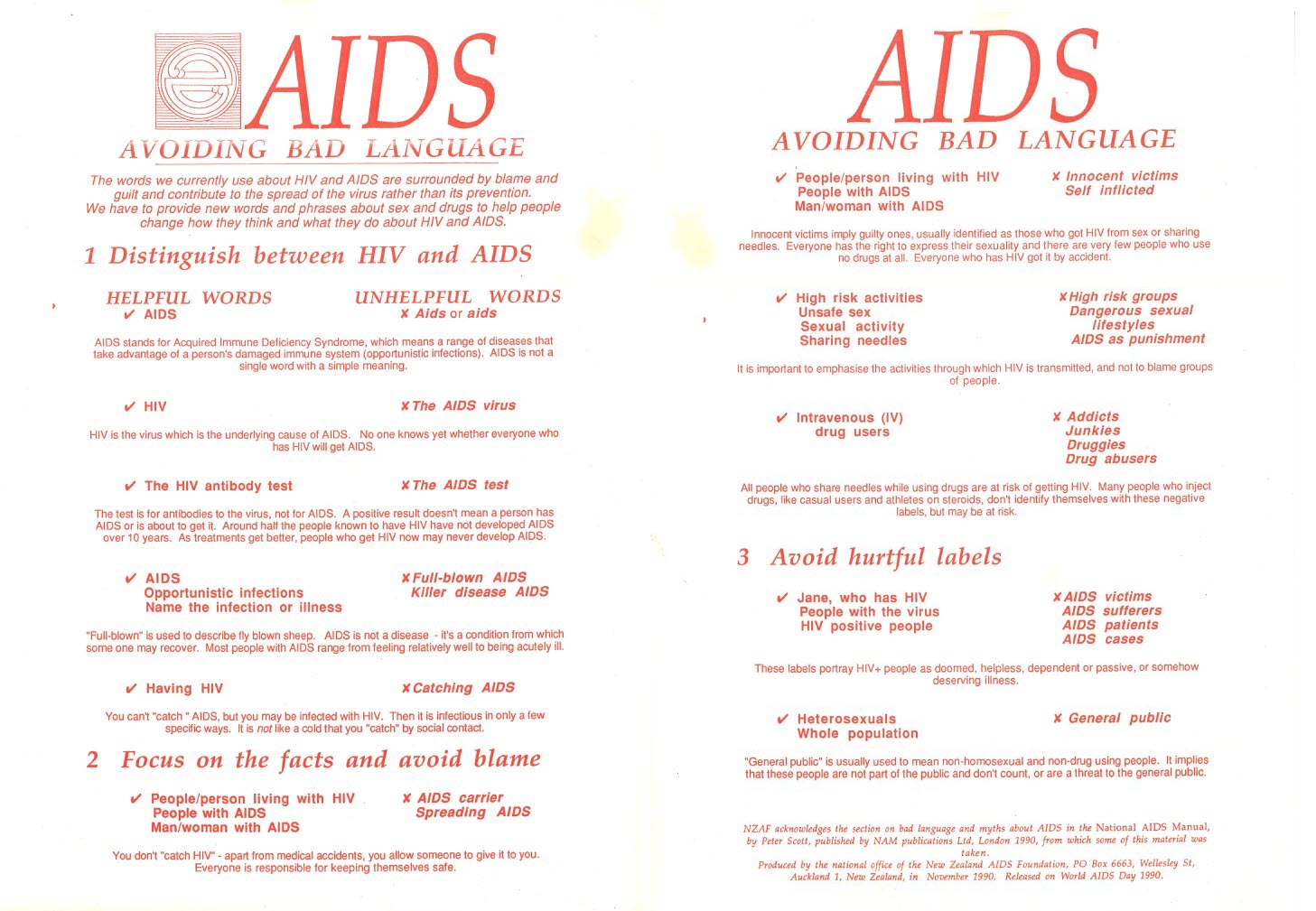

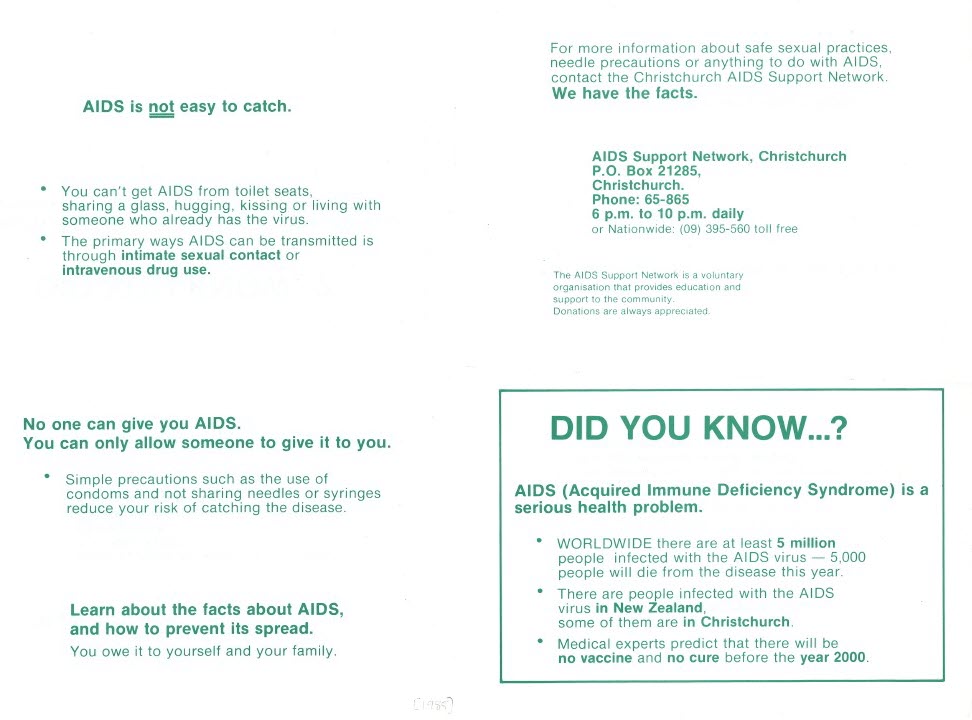

AIDS myth busting from the AIDS Support Network.

AIDS is not easy to catch. AIDS Support Network, Christchurch, 1988? Ephemera Collection, Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago.

Where AIDS-related information was created by the gay community, it tended to be straightforward, with more explicit discussion around ways in which the virus was understood to be transmitted, one example being Bruce Burnett’s article ‘Reducing the risks: AIDS in the gay ghetto.’[xiii] A pamphlet ‘AIDS choices and chances’, created by the NGRC, and inserted in the July-August 1984 issue of Pink Triangle, emphasised the importance of a ‘calm response to the impact of the AIDS crisis upon intimate areas of people’s lives,’ saying ‘the stresses and strains generated by fear, uncertainty, even panic, are potentially as damaging as AIDS itself’.[xiv]

Mainstream media however could be seen to perpetuate misinformation; a reporter in conversation with the Christchurch chair of the Haemophilia Society, who was waiting to hear if he had been exposed to the virus, described the man’s attempts to protect his family: ‘he always has to be careful. He uses his own glass, towel, or face cloth – just in case’.[xv] Professionals and the media appeared to willingly take the opportunity to further stigmatise other groups too: one article reported on an Auckland virologist’s suggestion that sex workers be licenced and subject to frequent mandatory health screenings to control the ‘killer virus’ and limit its spread among ‘the families and girlfriends of men who slept with infected street girls’.[xvi]

Pink Triangle highlighted the challenges the community faced when seeking support from the medical system. Where an ODT article in 1984 declared ‘Nurses ready to care for AIDS patients’[xvii] this obscured other stories. That same year, the first AIDS patient in New Zealand was transferred to New Plymouth, his place of origin, from Sydney. The Taranaki Herald, according to Pink Triangle, reported ‘a nurse […] would resign rather than treat the AIDS patient’.[xviii] Similarly, the AIDS Support Network reported difficulties procuring a location for a clinic. An Auckland public health unit had been suggested as a base, but the existing staff objected, one saying ‘[…] the AIDS clinic fits very uneasily into family health work’ and ‘there are a number of places in town far more suitable. For instance, in the rooms of general practitioners who are sympathetic to AIDS people’.[xix] While it is unpleasant to read these quotes, Pink Triangle clearly saw a reason to report them.

Phil Parkinson (administrator of the Lesbian and Gay Rights Resource Centre at the time), in a rare example of a gay voice being welcomed into a mainstream media space, argued for the importance of Homosexual Law Reform, stating that the AIDS crisis would only grow if it remained illegal to share information about risks. While prosecution remained a possibility, the stakes were too high to potentially out oneself when seeking information around prevention. He emphasised, too, that ‘AIDS is a blood disease not a homosexual one. It is caused by a virus and, like all viruses, can infect anybody.’[xx]

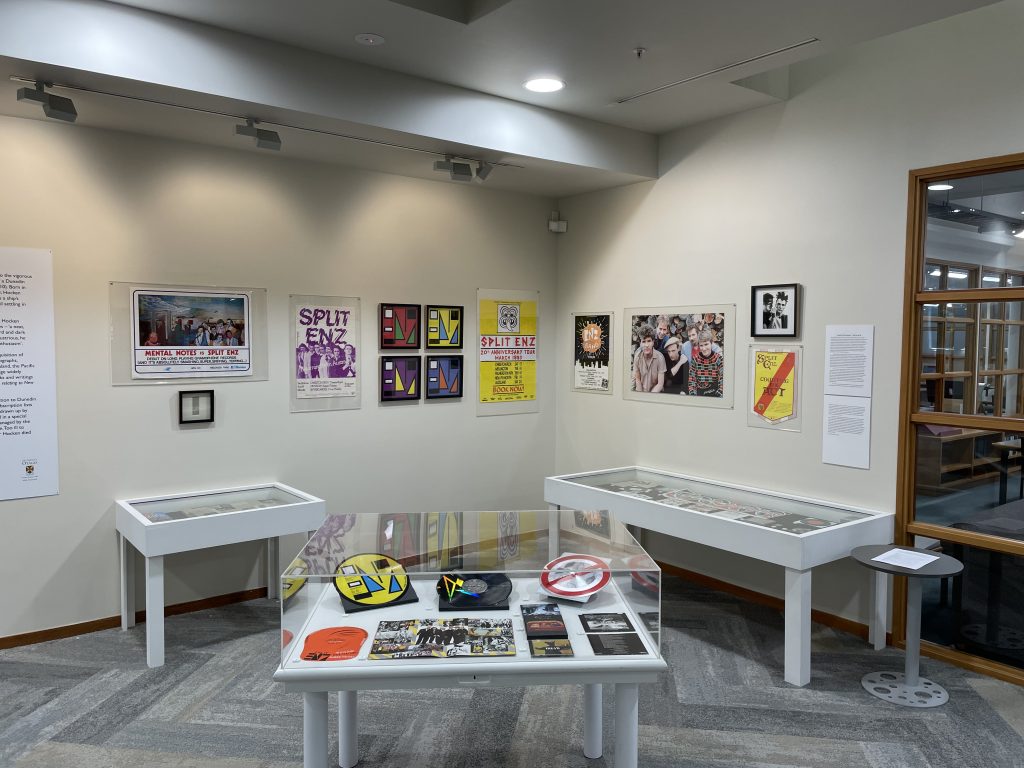

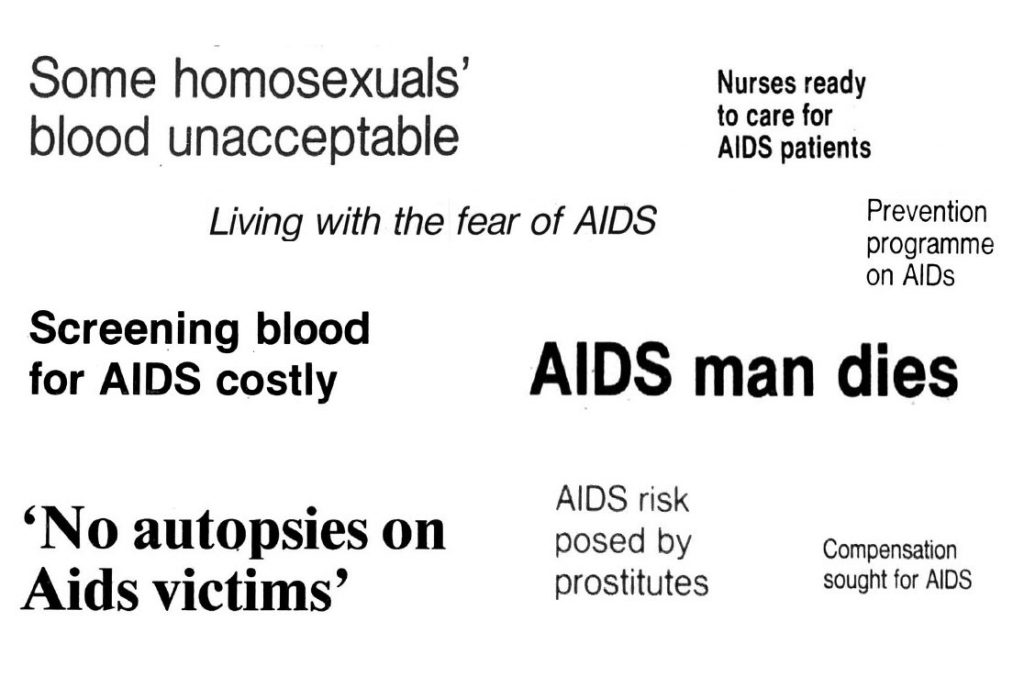

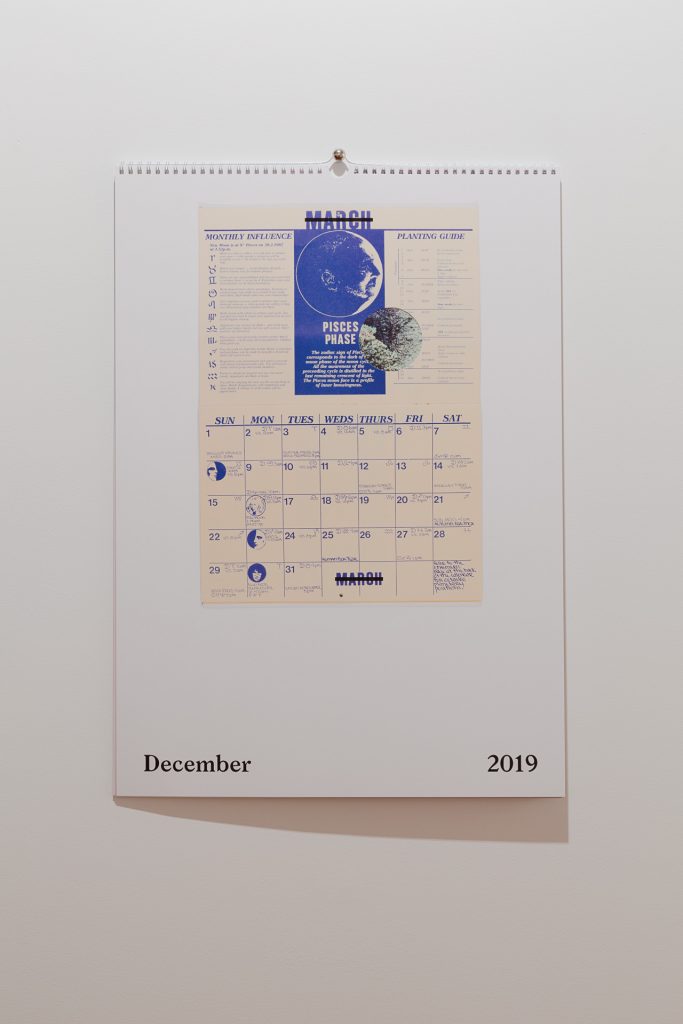

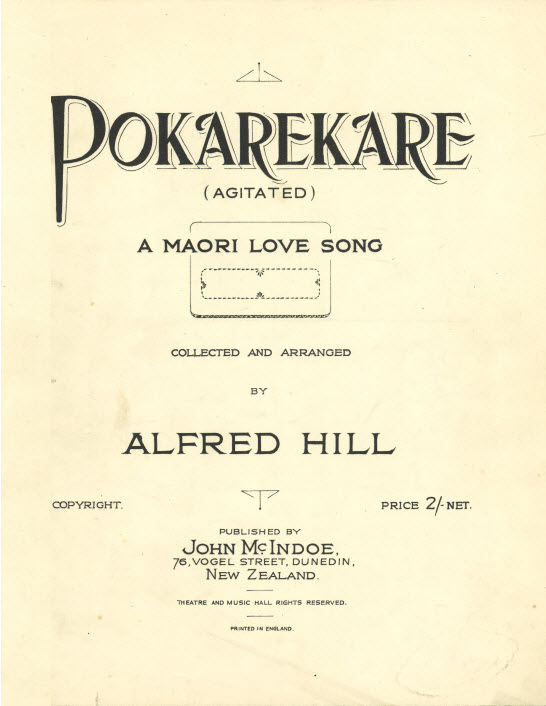

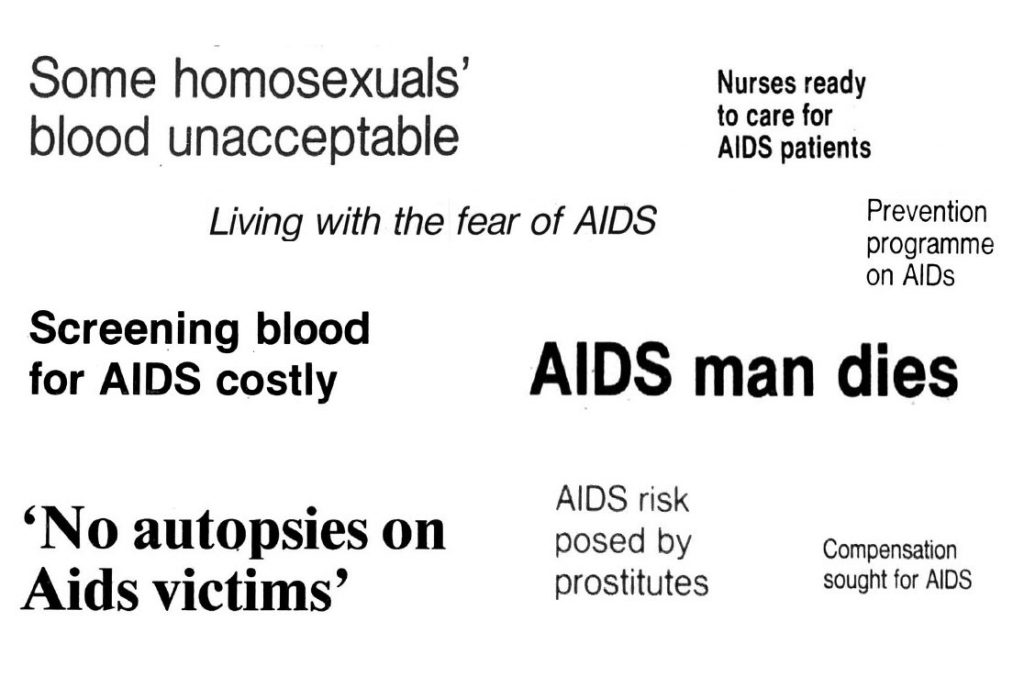

A selection of potentially stigmatising headlines from the Otago Daily Times.

Left to right, top to bottom: Some homosexuals’ blood unacceptable,10 May 1983, p.24; Nurses ready to care for AIDS patients, 11 February 1984, p.3; Living with the fear of AIDS, 10 April 1985, p.12; Prevention programme on AIDs, 4 August 1984, p.32; Screening blood for AIDS costly, 18 May 1985, p.12; AIDS man dies, 3 June 1985, p.5; ‘No autopsies on AIDS victims’, 27 March 1990, p.5; AIDS risk posed by prostitutes, 20 August 1985, p.15; Compensation sought for AIDS, 19 April 1985, p.2.

Meanwhile, in an ODT article headed ‘Living with the fear of AIDS’, a representative of the Haemophilia Society indicted the ‘homosexual community of using the AIDS situation for gaining political end such as gaining support for the Homosexual Law Reform Bill.’[xxi] While it is important to recognise haemophiliacs as another group vulnerable to AIDS, this seemed an unnecessarily opportunistic dig at an already deeply stigmatised group fighting for human rights. The same Society queried if Accident Compensation Corporation support was available for those who received contaminated blood products through a transfusion.[xxii] From my observations of the ODT, stories such as these were more common than those that sought the voices of those from the gay community; let alone intravenous drug users who were also at great risk.

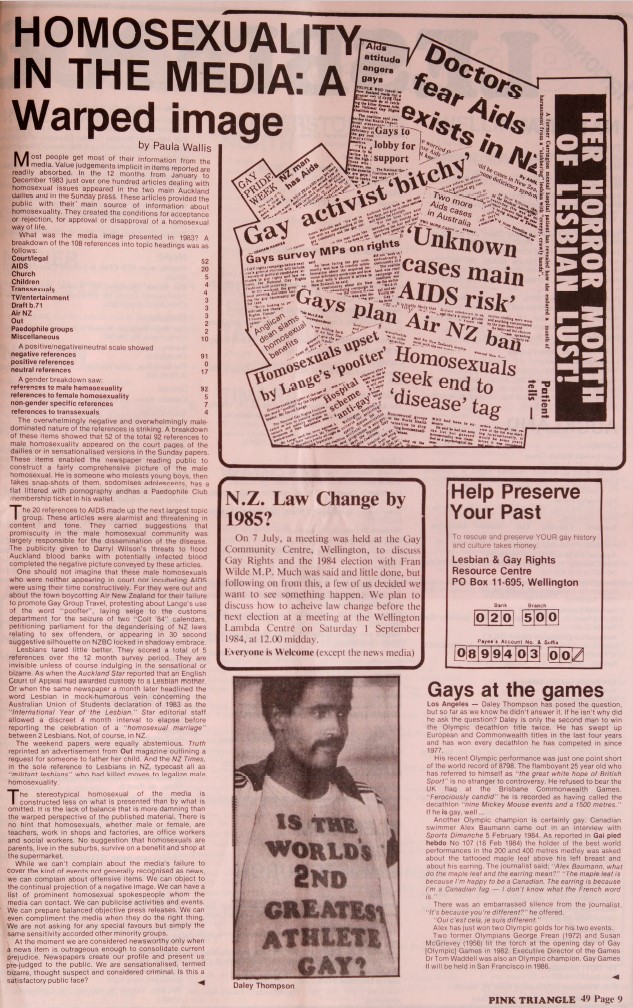

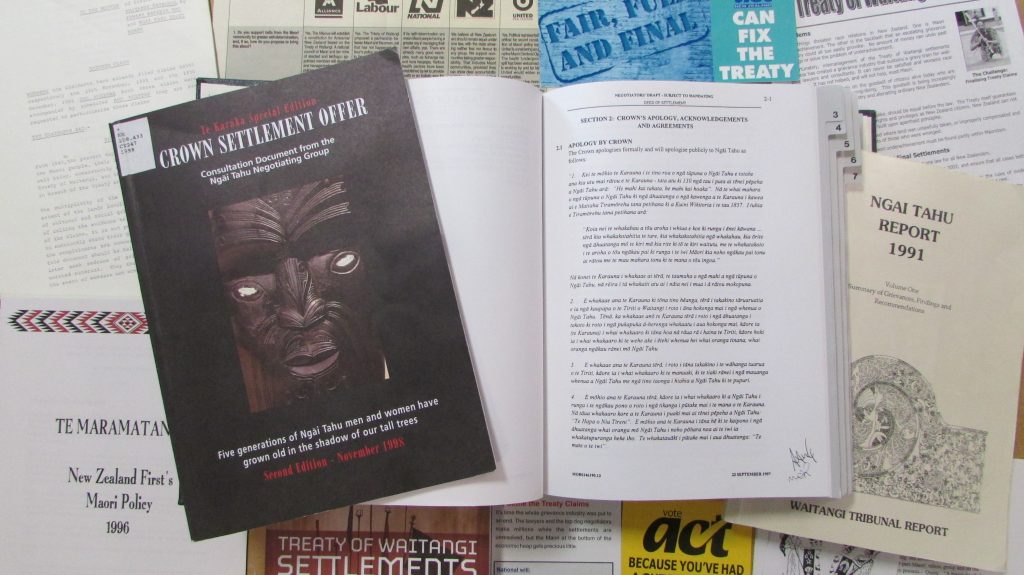

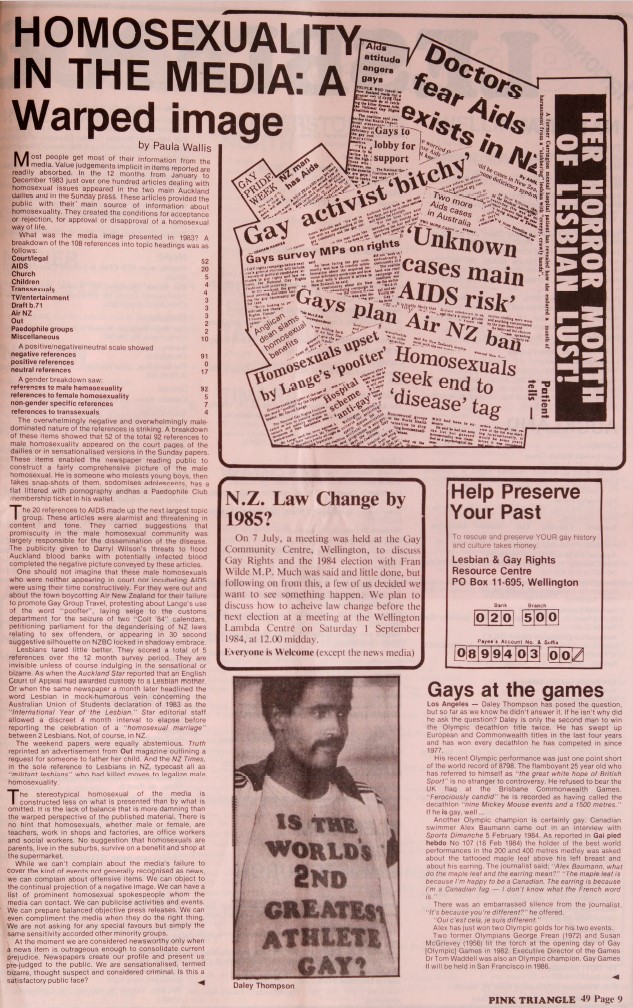

Pink Triangle was alert to how the community was perceived by the dominant media voice and the damage caused by negative stereotyping and rhetoric. The 1984 feature ‘Homosexuality in the media: a warped image’, by Paula Wallis, examined the content and tone of Auckland newspapers in the previous year. Wallis’ findings were ‘overwhelmingly negative’ in the way they referred to the homosexual population. References to AIDS were ‘alarmist and threatening’, predominantly blaming ‘promiscuity’ for the ‘dissemination of the disease.’ Wallis stated: ‘we are considered newsworthy only when a news item is outrageous enough to consolidate current prejudice.’[xxiii] In short, the community was othered and not permitted to share their stories with the wider society they lived in. This was not a fresh concern: in 1981, the NGRC published the guide How to work with the media: a manual for lesbian and gay rights groups.

‘Homosexuality in the media: a warped image’. Pink Triangle, Issue 49, September-October 1984, p.9

As a child of the 1980s, my first clear awareness of AIDS in media representation was the case of young Eve Van Grafthorst. Van Grafthorst received HIV contaminated blood as an infant in Australia, and was ostracised. Her family moved to Aotearoa where she became a prominent figure in the AIDS media discourse until her 1993 death. Considering the contrasts explored above in how the gay community and AIDS was portrayed by Pink Triangle versus more conventional media, it is not surprising that Eve’s death was where my attention was directed. Yet by the end of the year in which Van Grafthorst died, there had been 340 known AIDS deaths since the first notified cases of 1984, and the majority of these lives lost probably received no media attention, let alone a compassionate framing.[xxiv]

Medical progress now means we, at least in the developed world, can look to the number of people living with HIV, rather than dying of AIDS, yet HIV vaccines are still in the experimental stage.[xxv] It is hard to not contrast this with the rapid development of vaccines for COVID-19. There are myriad reasons why the latter were able to be developed so quickly, but a cynical person might question the reasons behind the slower pace on the former when 36.3 million people globally have died of HIV.[xxvi]

Ultimately, this examination supplies us with useful reminders for every time we engage with news media. Whose voices are prioritised? Whose knowledge and opinions are dismissed or never sought? Who benefits – and who loses out – when the story is presented as it is? Where else should we look to get a fuller picture?

[i] Cisgender describes ‘someone whose gender aligns with that which they were assigned at birth. The opposite of transgender.’ ‘Rainbow terminology: Sex, gender, sexuality & other key terms’, InsideOUT Kōaro, https://www.insideout.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/InsideOUT-rainbow-terminology-August-2021.pdf (accessed 30 March 2022)

[ii] ‘Gay pneumonia? Not really, says researcher’, Pink Triangle, Issue 27, September 1981, p.1

[iii] ‘Some homosexuals’ blood unacceptable’, Otago Daily Times, 10 May 1983, p.24

[iv] ‘Hets miss out on gay blood’, Pink Triangle, May/June 1983, p.1

[v] ‘To give or not to give’, Pink Triangle, Issue 44, July-September 1983, p.2

[vi] ‘Gays co-operate’, Pink Triangle, Issue 44, July-September 1983, p.3

[vii] ‘Blood test; network cautious’ Pink Triangle, Issue 50, November-December 1984, p.3

[viii] Ibid., p.19

[ix] ‘Crisis – what crisis?’ Pink Triangle, Issue 41, Summer 1982/83, p.1

[x] Ibid.

[xi] ‘NGRC hits back on AIDS’, Pink Triangle, Issue 44, July-September 1983, p.3

[xii] ‘AIDS Support Network’ [advertisement], Pink Triangle, Issue 50, November-December 1984, p.19

[xiii] ‘Reducing the risks: AIDS in the gay ghetto’, Pink Triangle, Issue 48, July-August 1984, p.13

[xiv] ‘AIDS choices and chances’, National Gay Rights Coalition of New Zealand [pamphlet] Pink Triangle, Issue 48, July-August, 1984

[xv] Living with the fear of AIDS, Otago Daily Times, 10 April 1985, p.12

[xvi] ‘AIDS risk posed by prostitutes’, Otago Daily Times, 20 August 1985, p.15

[xvii] ‘Nurses ready to care for AIDS patients’, Otago Daily Times, 11 February 1984, p.3

[xviii] ‘AIDS man transferred’, Pink Triangle, Issue 46, March/April 1984, p.1

[xix] ‘Nurses object’, Pink Triangle, Issue 51, Summer, 1984-85, p.1

[xx] ‘AIDS and homosexual law’, Otago Daily Times, 20 June 1985, p.4

[xxi] ‘Living with the fear of AIDS’, Otago Daily Times, 10 April 1985, p.12

[xxii] ‘Compensation sought for AIDS’, Otago Daily Times, 19 April 1985, p.2

[xxiii] ‘Homosexuality in the media: a warped image’, Pink Triangle, Issue 49, September-October 1984, p.9

[xxiv] AIDS – New Zealand, AIDS Epidemiology Group, Issue 20, February 1994, https://www.otago.ac.nz/aidsepigroup/otago714396.pdf (accessed 29 March 2022)

[xxv] ‘Experimental mRNA HIV vaccine shows promise in animals’, National Institutes of Health, 11 January 2022, https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/experimental-mrna-hiv-vaccine-shows-promise-animals (accessed 29 March 2022)

[xxvi] ‘Global Health Observatory HIV/AIDS’, World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/hiv-aids (accessed 30 March 2022)

References

Web resources

KFF, Global HIV/AIDS Timeline, 20 July 2018, https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/timeline/global-hivaids-timeline/ (accessed 23 March 2022).

Lesbian & Gay Archives of New Zealand Te Pūranga Takatāpui o Aotearoa, Out of the ashes, December 1986, https://www.laganz.org.nz/trust/ashes.html, (accessed 22 March 2022).

New Zealand AIDS memorial quilt, Eve Van Grafhorst 17 July 1982 – 20 November 1993, https://aidsquilt.org.nz/eve-van-grafhorst-7/, (accessed 28 March 2022).

Publications

National Gay Rights Coalition of New Zealand, How to work with the media: a manual for lesbian and gay rights groups. National Gay Rights Coalition, Wellington, 1981.

National Gay Rights Coalition of New Zealand, National Gay Rights Coalition of New Zealand, National Gay Rights Coalition of New Zealand, Auckland, 1978.

New Zealand AIDS Foundation, Living well with HIV: Piki te ora. NZAF, Te Tūāpapa Mate Āraikore o Aotearoa, Wellington, 2017.