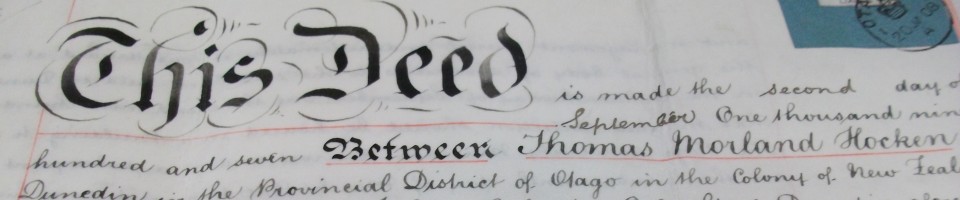

Blog post researched and written by Kate Guthrie, Collections Assistant – Archives

Remember autograph books?

For those of us old enough to have had one back in the day, they were the Facebook of the pre-internet age; a little album to collect the thoughts and witticisms of your friends, family and occasionally even the famous. Sometimes kept and treasured for many years after the last entries were written in them, autograph books could become memory-holders too, for friends the album-keeper had lost touch with and older family members who’d passed away.

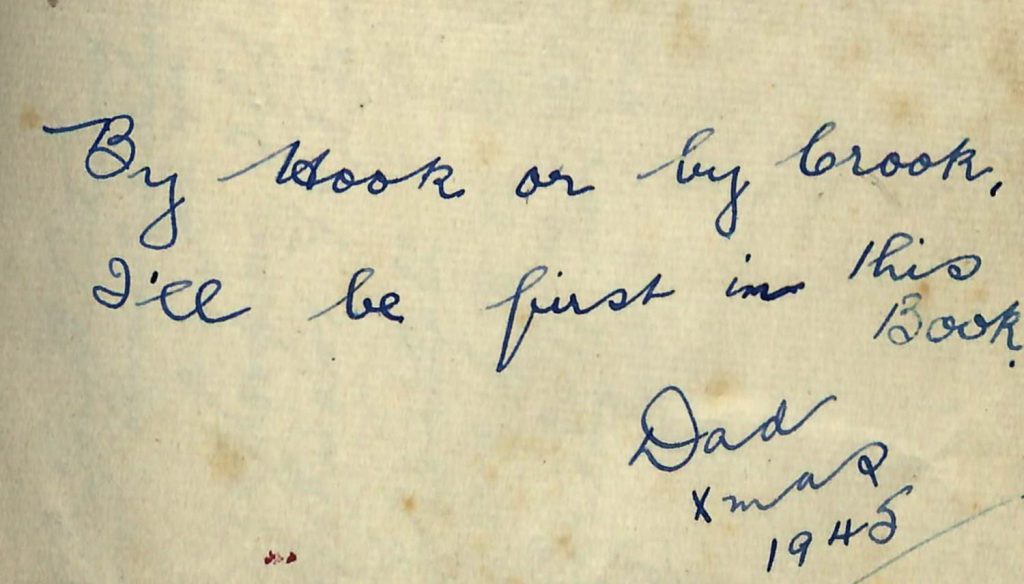

An autograph book tended to arrive sometime around the pre-teen/early teenage years – perhaps in a Christmas stocking – and the first autographs to grace the new album might well be the ‘rellies’ gathered for Christmas lunch. Everyone had a favourite verse or two they carefully wrote in – and the tricky part was coming up with something no-one else had written before you. It was a good idea to get in early, as Nelson Stockbridge’s father did back in 1945…

By Hook or by Crook,

I’ll be first in this Book

Dad, Xmas 1945

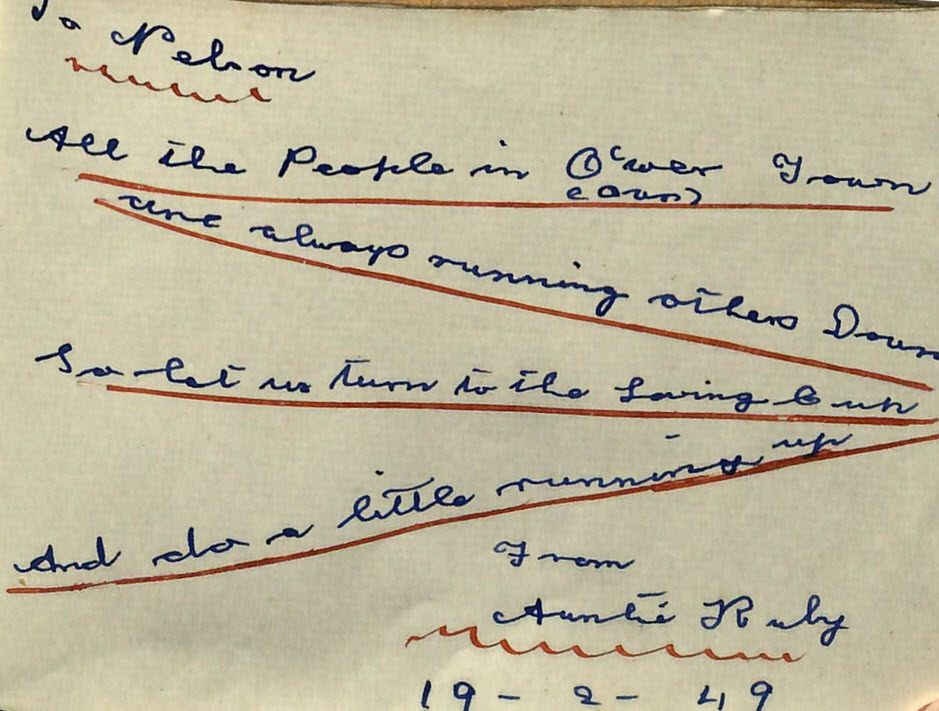

Nelson’s Auntie Ruby had some sage advice a few years later…

All the people o’er our town

Are always running people down

So let us turn to the Loving Cup

And do a little running up

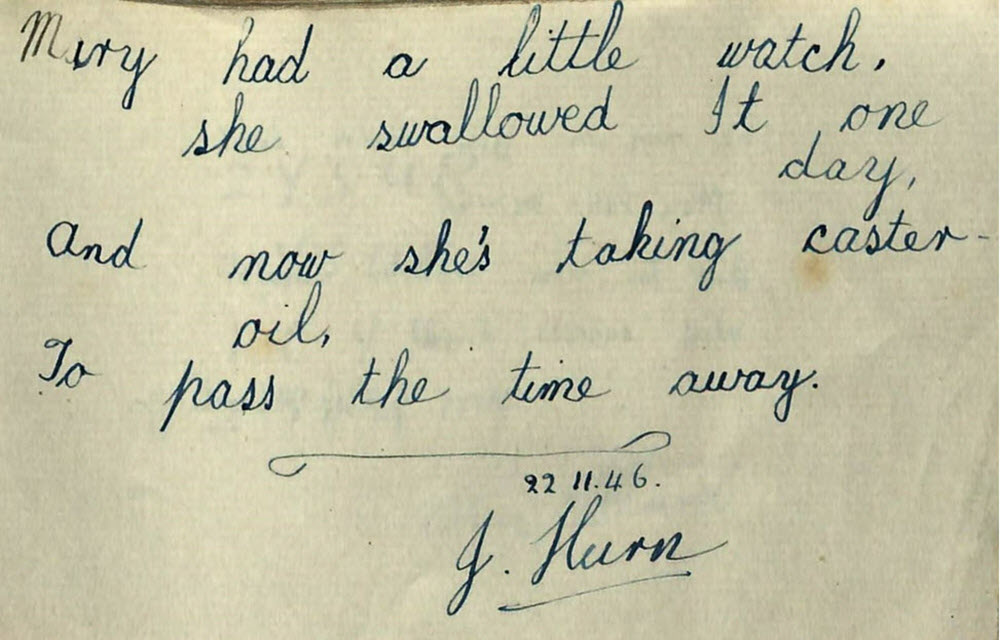

Another personal favourite from Nelson’s album is this one from J. Hurn, dated 1946:

Mary had a little watch

She swallowed it one day

And now she’s taking castor oil

To pass the time away.

We don’t know much about Nelson Stockbridge, but there are one or two clues in the autograph book itself and in its provenance. The album was found in the loft of the hall of All Saints’ Anglican Church, Dunedin and donated to the Hocken by the All Saints’ vicar in 2009. It includes references to Terrace End School and Brooklyn School, suggesting Nelson lived in Palmerston North and Wellington as a boy.

Time to hit the search engines…

Births must have occurred more than one hundred years ago to be searchable on the Births, Deaths and Marriages historical database. Deaths, however, can be searched right up until the present day and often reveal a birth date or age as well. If you’re interested in family history research, it’s something worth remembering.

Nelson Stockbridge is a less-common name, which also makes a quick search worthwhile. And there’s a promising hit: Nelson William Stockbridge died in 2009 (coincidentally the year his autograph book came to light), and his date of birth is given as 23 January 1935, meaning he was soon to turn eleven when he was given that Christmas autograph book.

And how did that book make its way to All Saints Anglican in Dunedin? That faithful workhorse Google uncovers a document that lists Rev. Nelson William Stockbridge as a Methodist minister, revealing a likely clergical link in Nelson’s adult years.

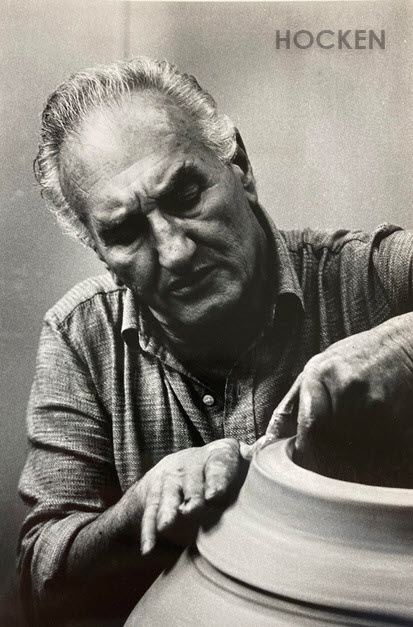

Nelson’s autograph book is one of many in the Hocken archival collection – and some of them are stunning. A stroll through the collections (or a search on Hākena) shows there was much more to autograph books than witty rhyming ditties, particularly if we step back a little earlier in their history.

So how long have autograph books been around? At a guess, I’d have said a century or so.

I’d have been wrong.

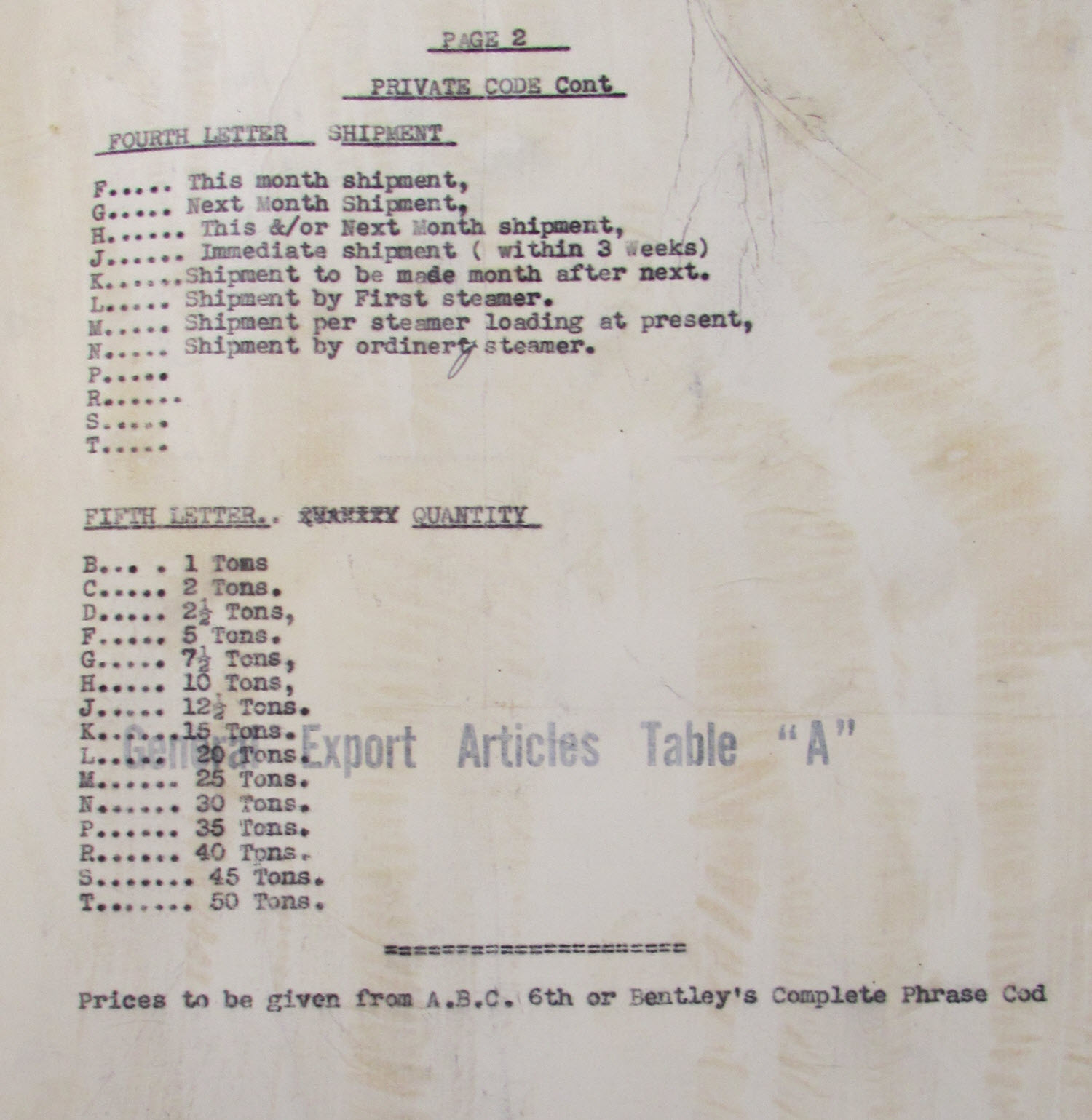

Autograph books originated in the mid-sixteenth century in Europe when travelling university students carried these small, leather-bound albums and collected the sentiments and comments of their patrons, mentors and companions – a bit like a pre-internet LinkedIn. In those times when only male offspring were deemed worth educating at universities, collecting autographs would have been a male-only occupation.

The first true autograph books appeared in German and Dutch linguistic regions, possibly originating in Wittenberg. (Thank you, Wikipedia).

Known as an album amicorum (‘book of friends’) or stammbuch (‘friendship book’), the oldest autograph book on record is that of Claude de Senarclens, an associate of John Calvin, and dates back to 1545. By the end of the century, they were common among students and scholars throughout Germany.

The Germans and Dutch may have invented the autograph book. But, from the evidence I’ve seen in the Hocken’s own autograph book collection, it was the women of Victorian and Edwardian times who took autograph collecting to a whole new artistic level.

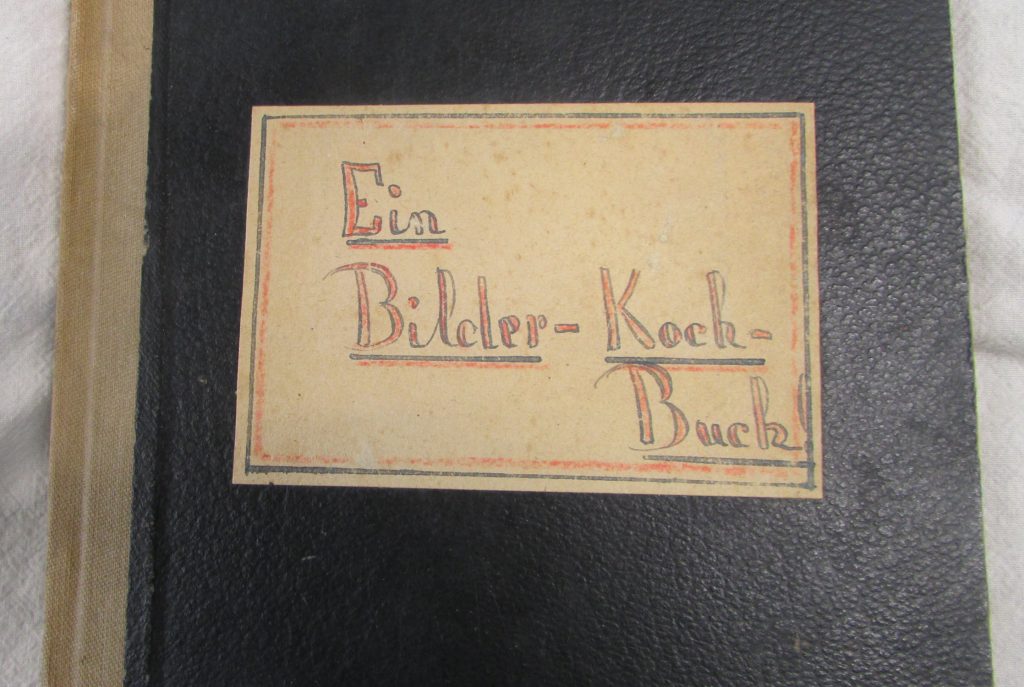

Margaret Simon, or Peggy as she was known, was one of eight children of James and Ellen Simon. The family owned a business, Simon Brothers, which imported and manufactured footwear, and their home was in Mornington, Dunedin.

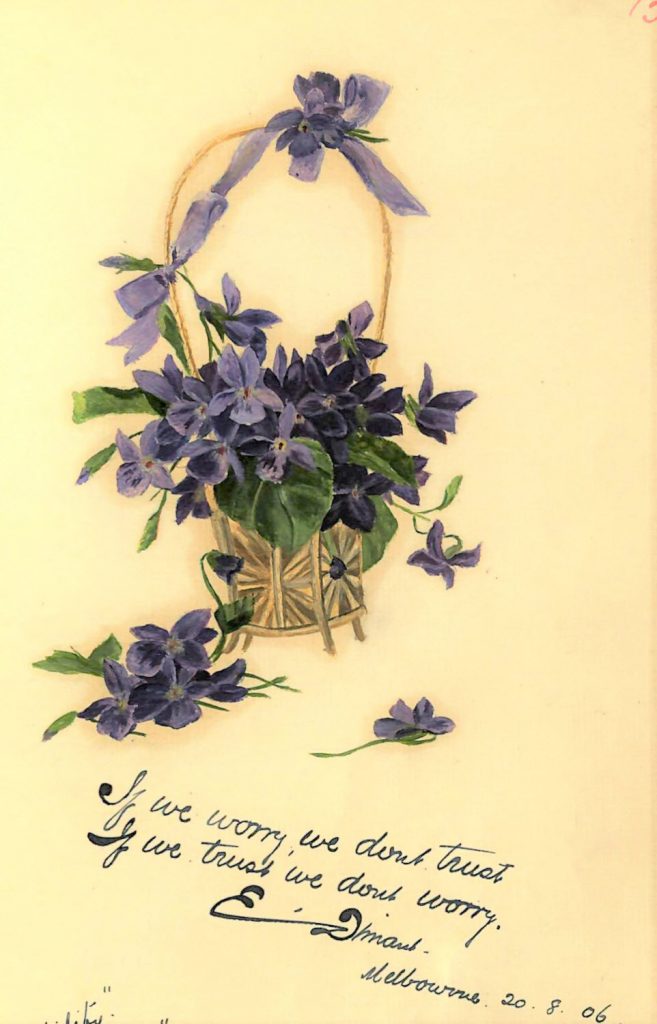

A beautiful autograph and sketchbook was kept by Peggy Simon from 1905 until around the time of her marriage to Rudolph Wark in 1910. Peggy and Rudolph settled in Christchurch after their marriage and the autograph book, along with a family photograph, was donated to the Hocken in 2010 by Peggy’s nephew, Herbert William Tennet.

The Simon family. Peggy is pictured standing back left. Simon, Margaret : Autograph and sketch book (1905-c.1910), MS-3564

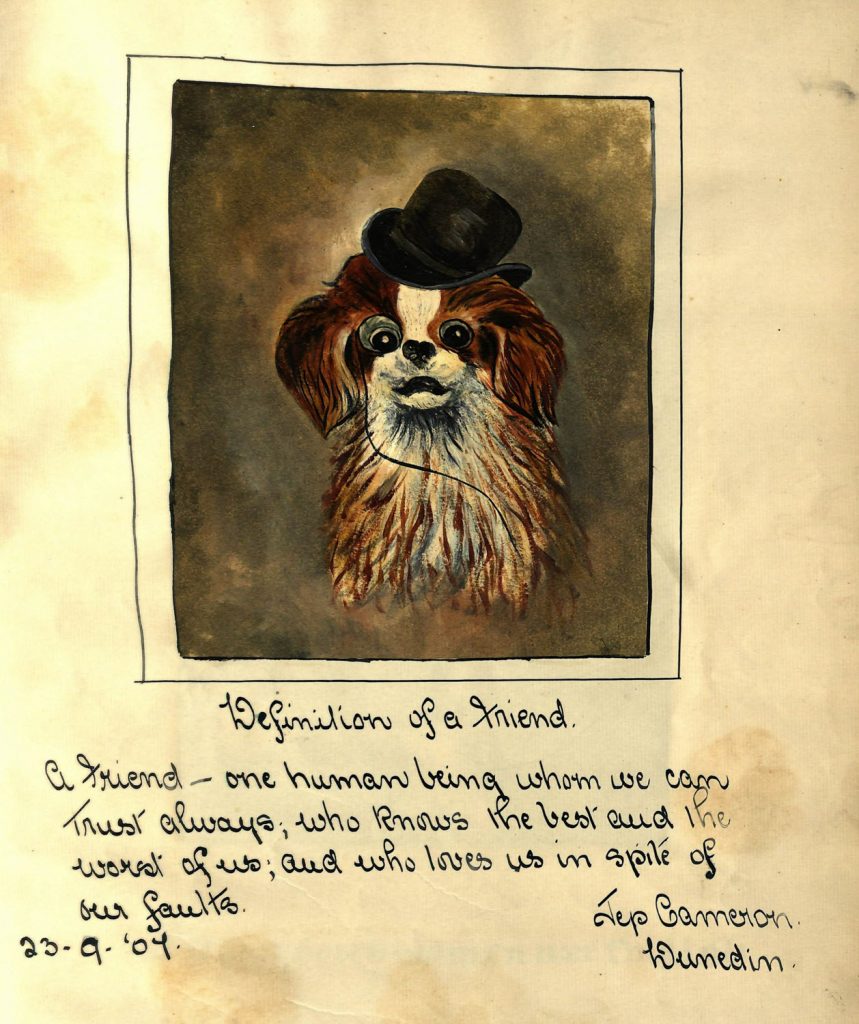

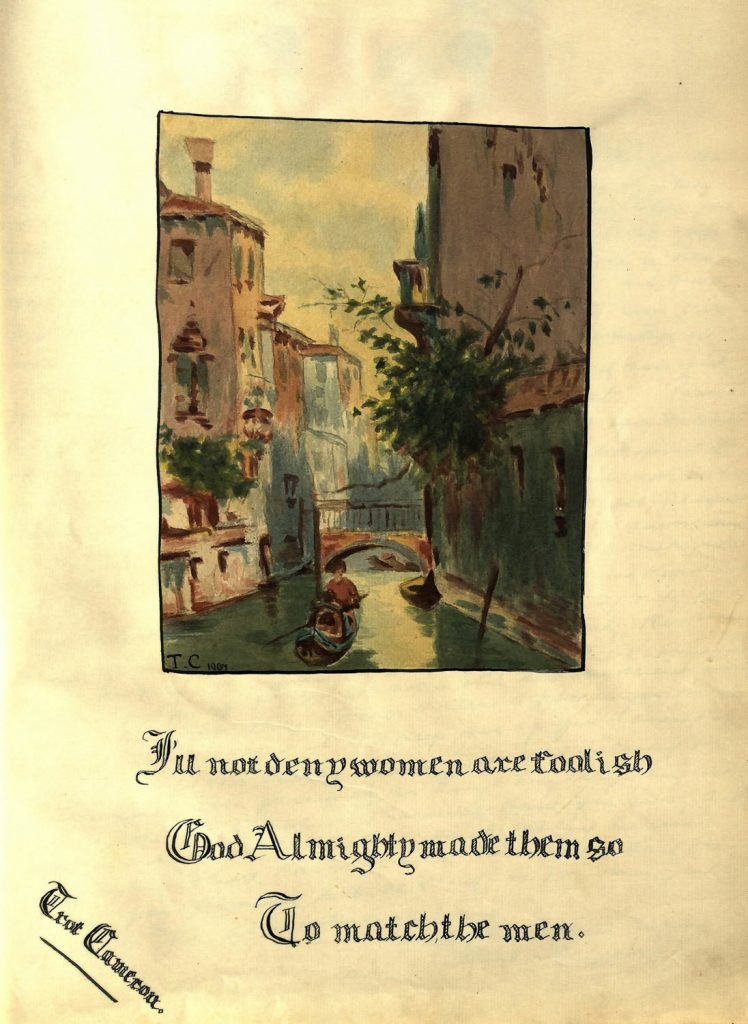

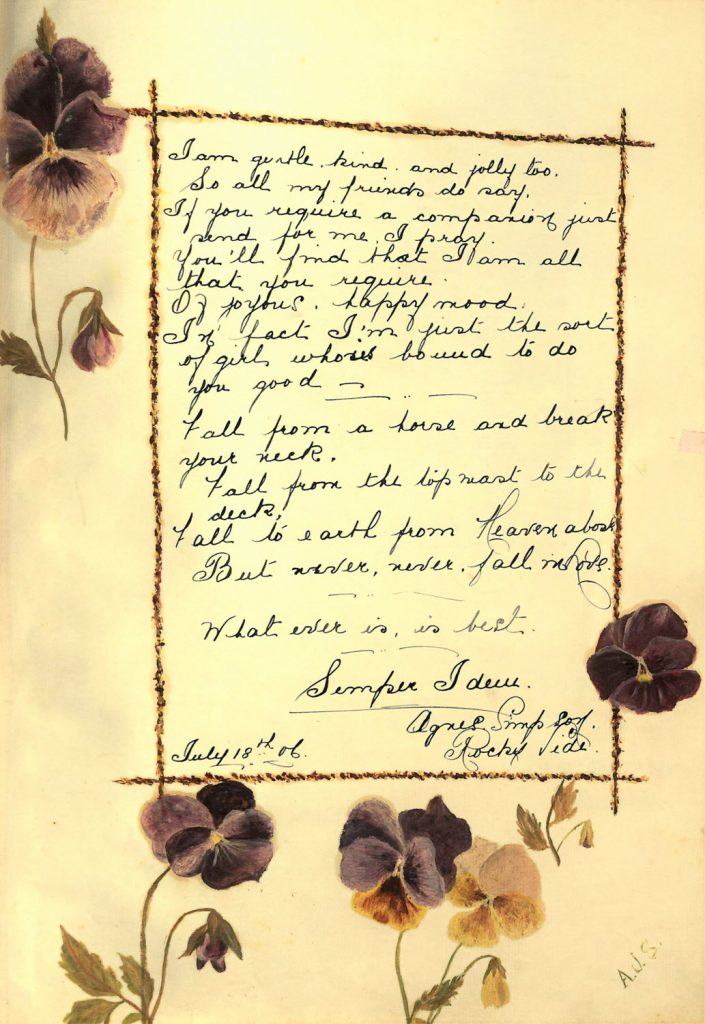

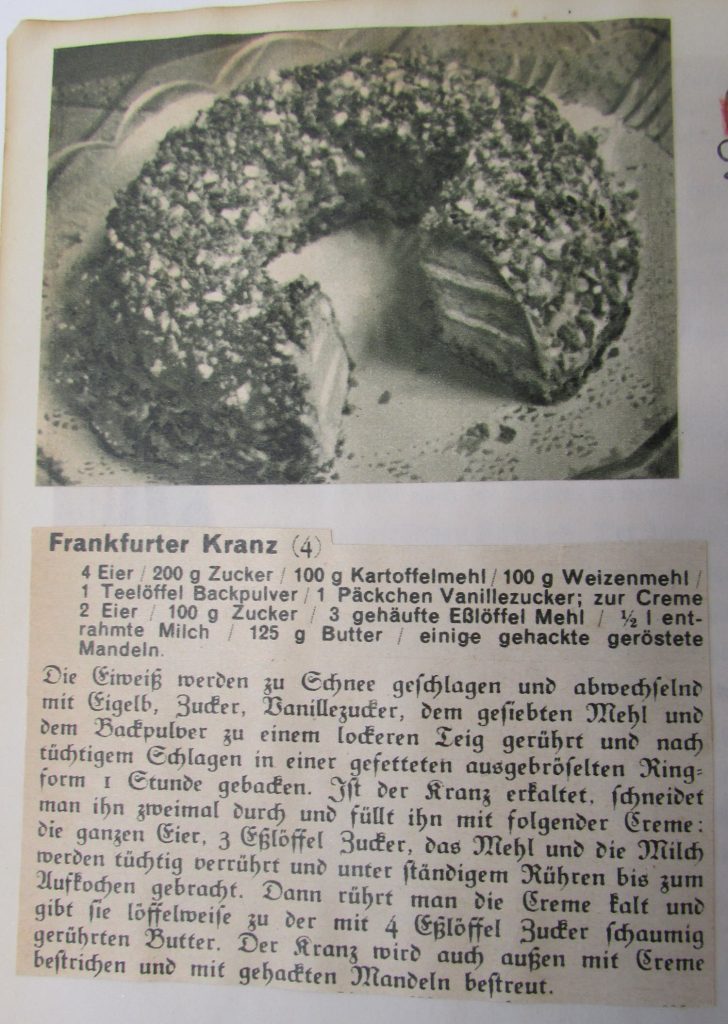

Autographers (is that even a word?) put a lot of time, skill and thought into creating their small piece of posterity in a friend’s autograph book. Just look at the illlustrations in these examples from Peggy Simon’s album.

Definition of a friend

A friend – one human being whom we can

Trust always, who knows the best and the

worst of us, and who loves us in spite of

our faults

23-9-07 Jep Cameron, Dunedin

I’ll not deny women are foolish

God Almighty made them so

To match the men.

T.C. 1907

Trot Cameron

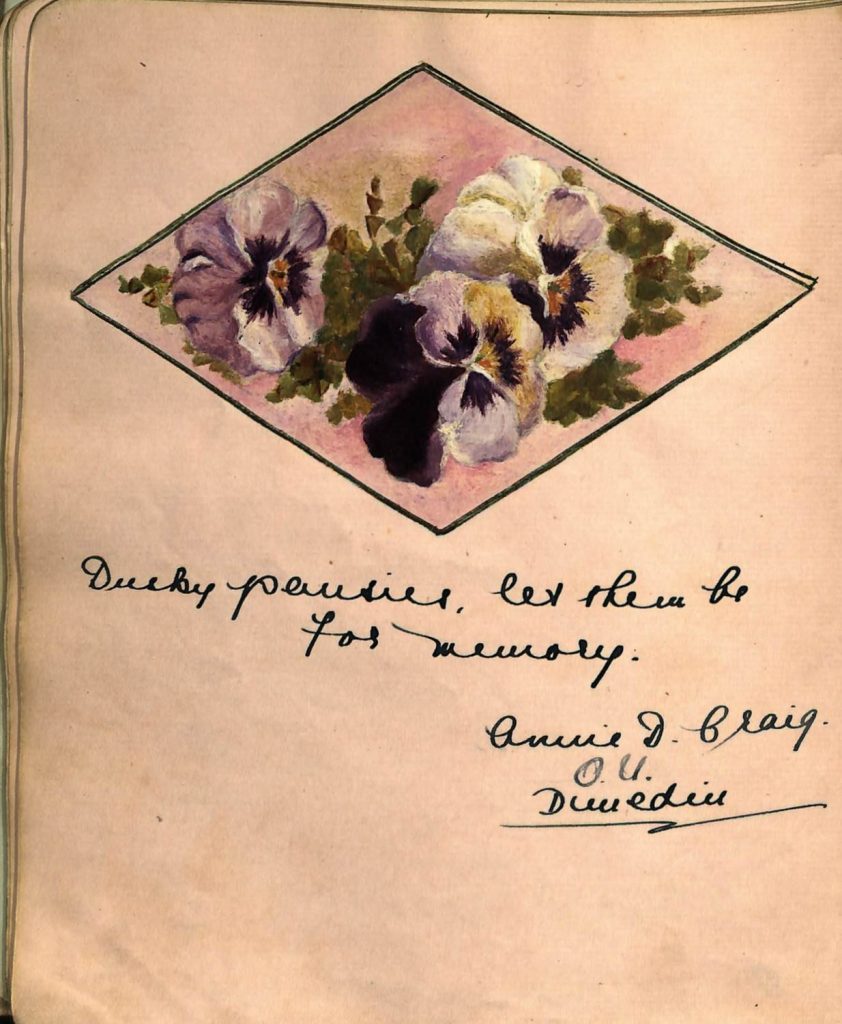

Flowers often appear in autograph illustrations and pansies seem to be a favourite. At first, I wondered why pansies, rather than forget-me-nots or rosemary (for remembrance). Was it because pansies are pretty, colourful and fun to paint?

A contributor to Isabella Blair’s autograph book revealed the answer – a phrase linked to Ophelia, in Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

There is pansies, that’s for thoughts…

Another contributor to Isabella’s album had a slightly different version of the same sentiment…

Dusky pansies, let them be for memory

Anne D. Craig

O.U.

Dunedin

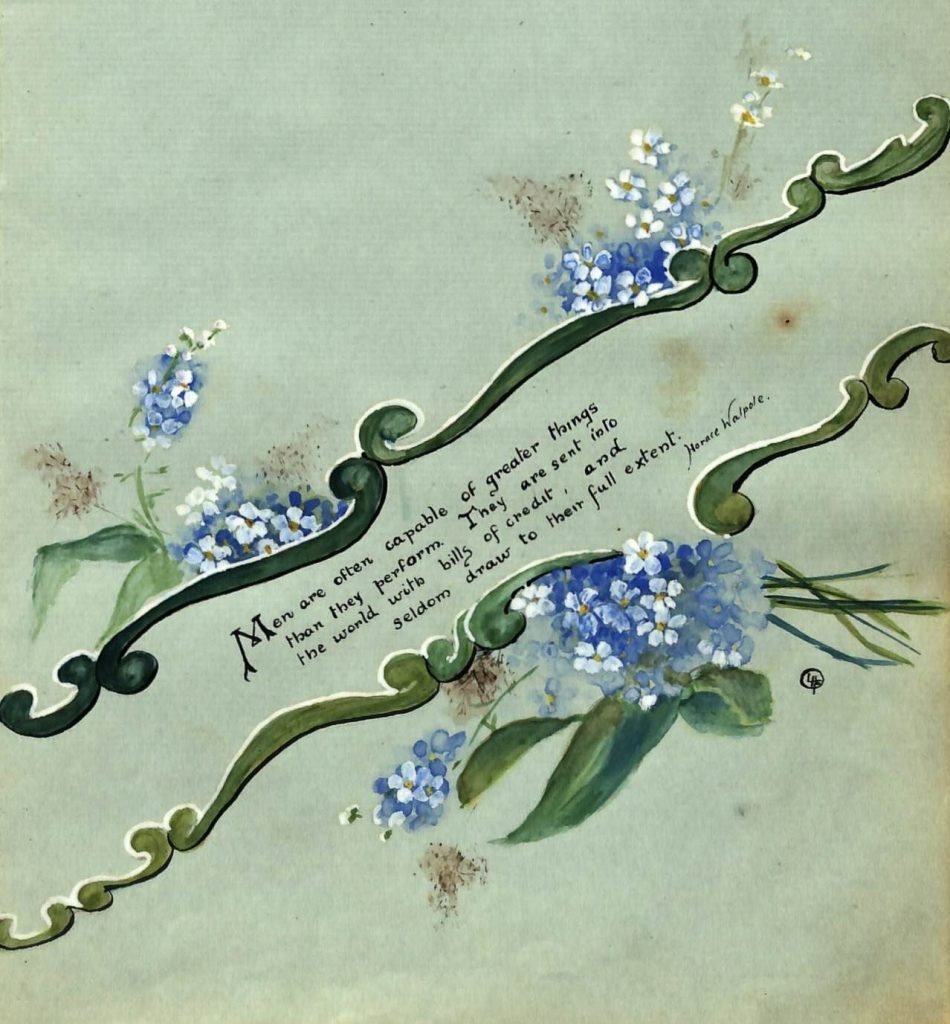

And of course, forget-me-nots do make the occasional appearance in these floral tributes.

Men are often capable of greater things

than they perform. They are sent into

the world with bills of credit, and

seldom draw to their full extent

Isabella Blair (later to be Isabella Tily) was a student of Dunedin Teachers’ College and Otago University and many of the contributors to her autograph album have added the abbreviations OU or TC after their names. Like many others of the Victorian/Edwardian period, the album is a reflection of Isabella’s early adult life. One friend has even sketched what seems to be a portrait of Isabella at that time.

Compare the sketch with this photograph of Isabella Tily in later years, when she and husband Harry Tily were keen members of the Dunedin Naturalists’ Field Club and Isabella wrote regular articles on birds for Dunedin’s Evening Star. (The bird in the photograph is a kererū fledgling which she raised after finding it fallen from its nest.)

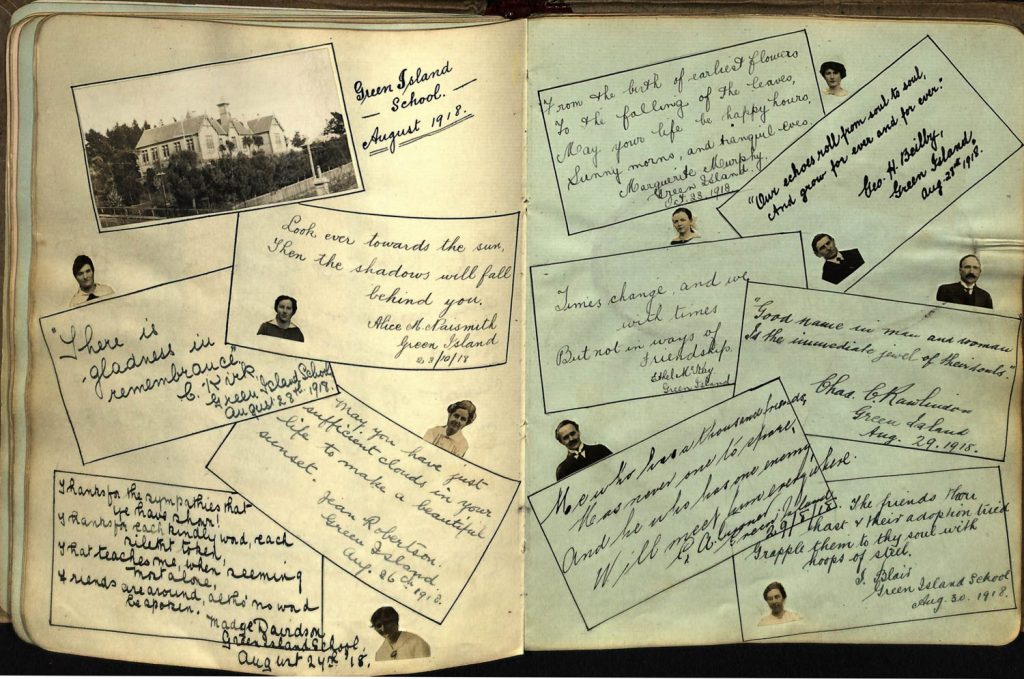

After completing her teacher training, Isabella went on to teach at Green Island School, just as the First World War was ending. She took her autograph book with her and collected the autographs, photographs and thoughts of her fellow teachers in 1918.

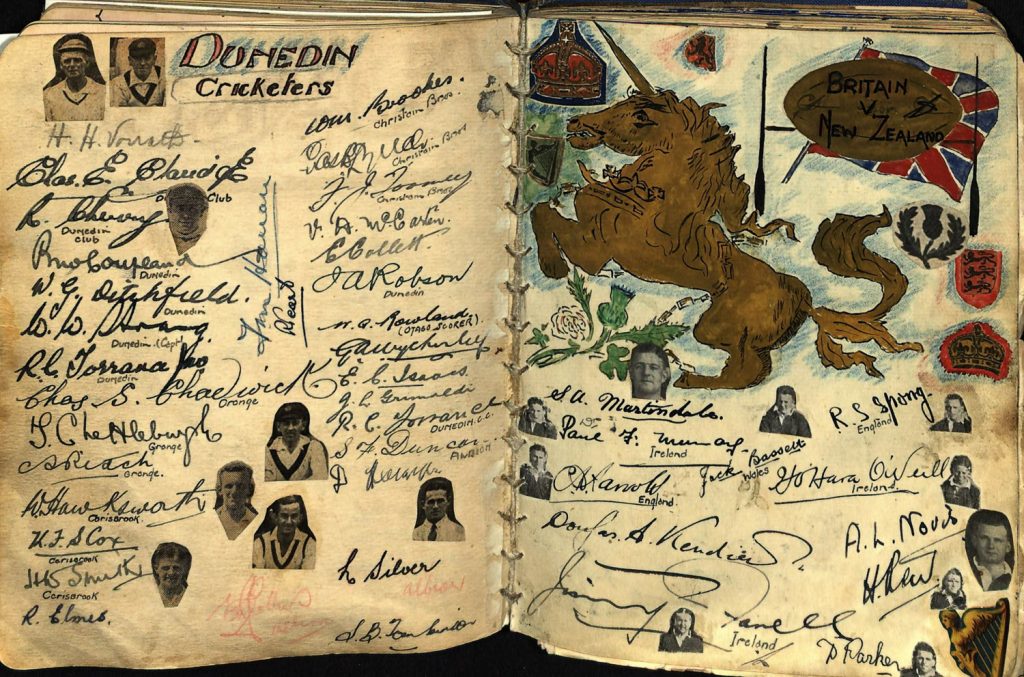

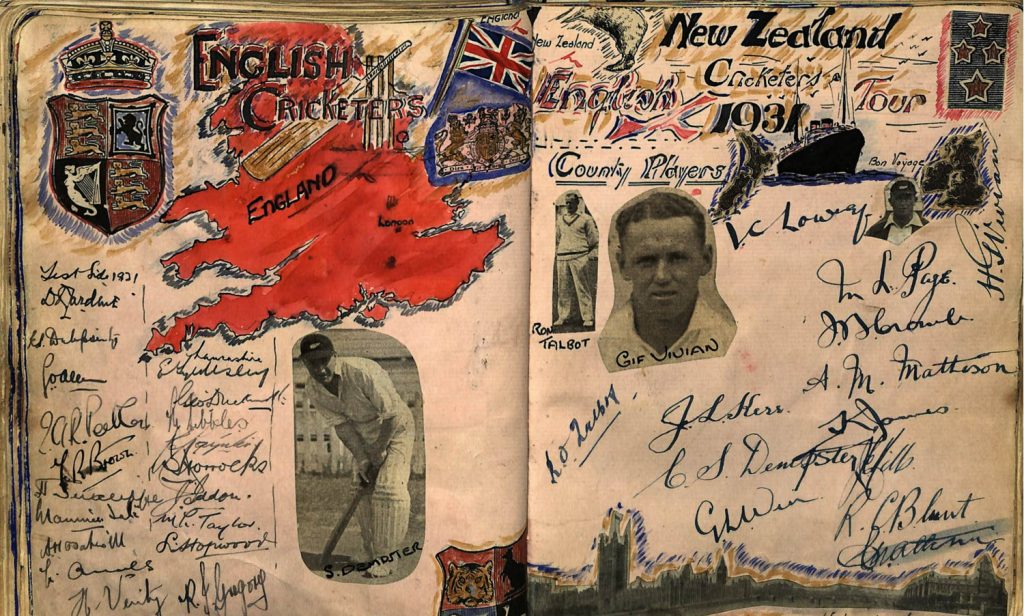

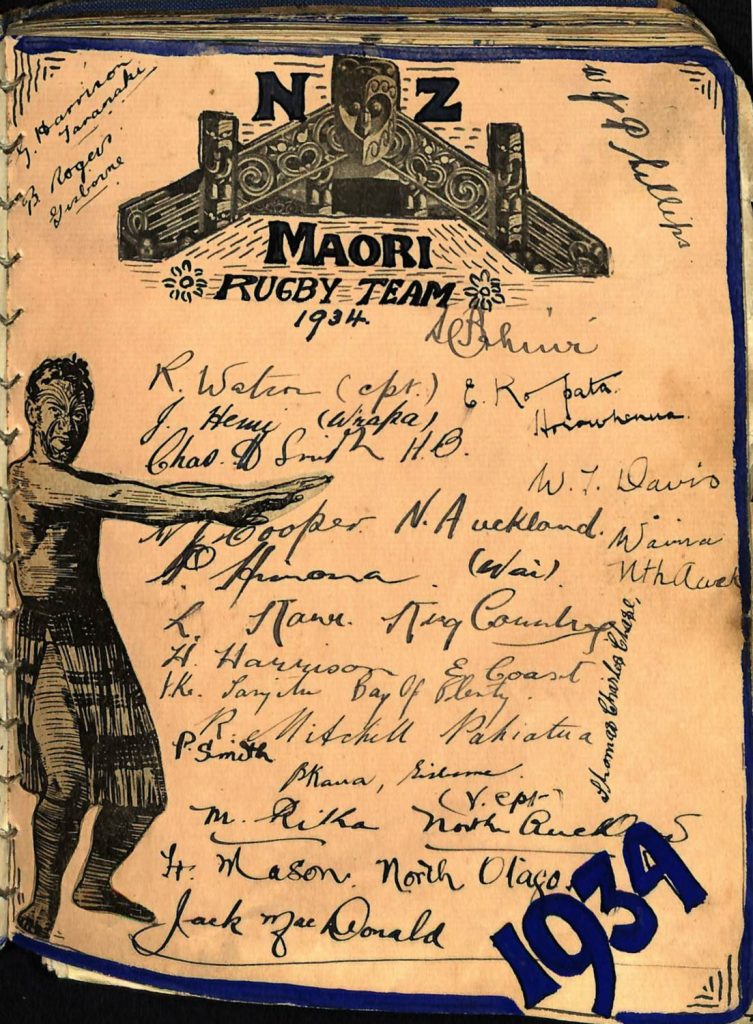

A few years later, Dunedin schoolboy Jack Smith was also a keen collector of autographs. Jack was an Otago Boys High School first eleven cricketer and avid sports fan. Picture a schoolboy, pen and autograph book in hand, racing across the playing field, collecting the signatures of his heroes at the end of the game. But Jack was more than an autograph collector. He also illustrated his album pages with schoolboy enthusiasm.

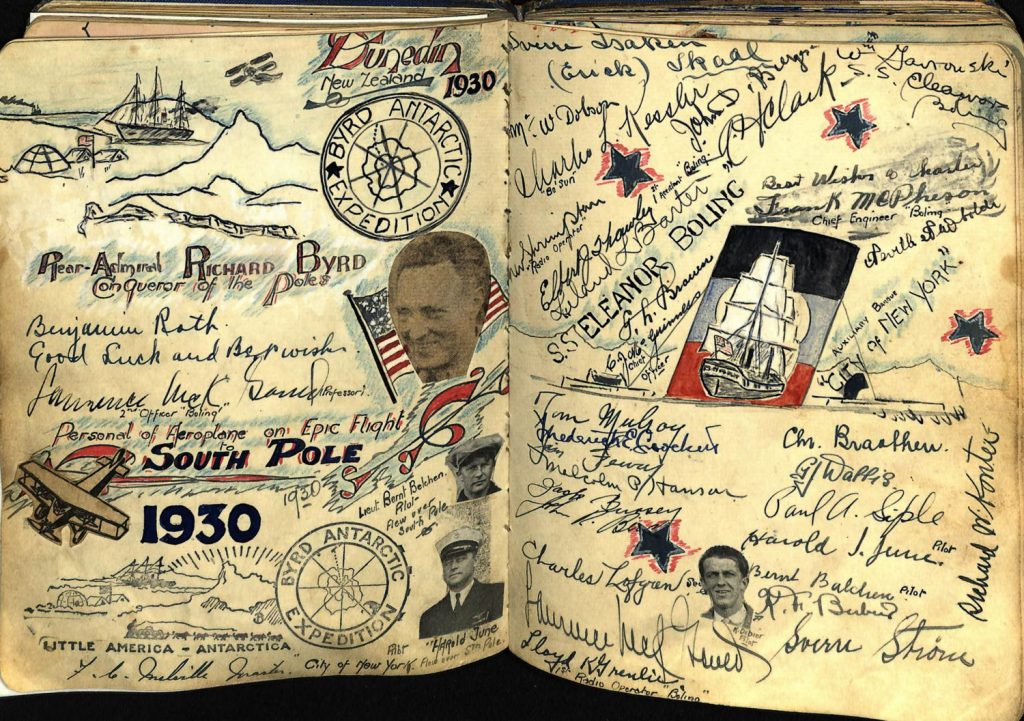

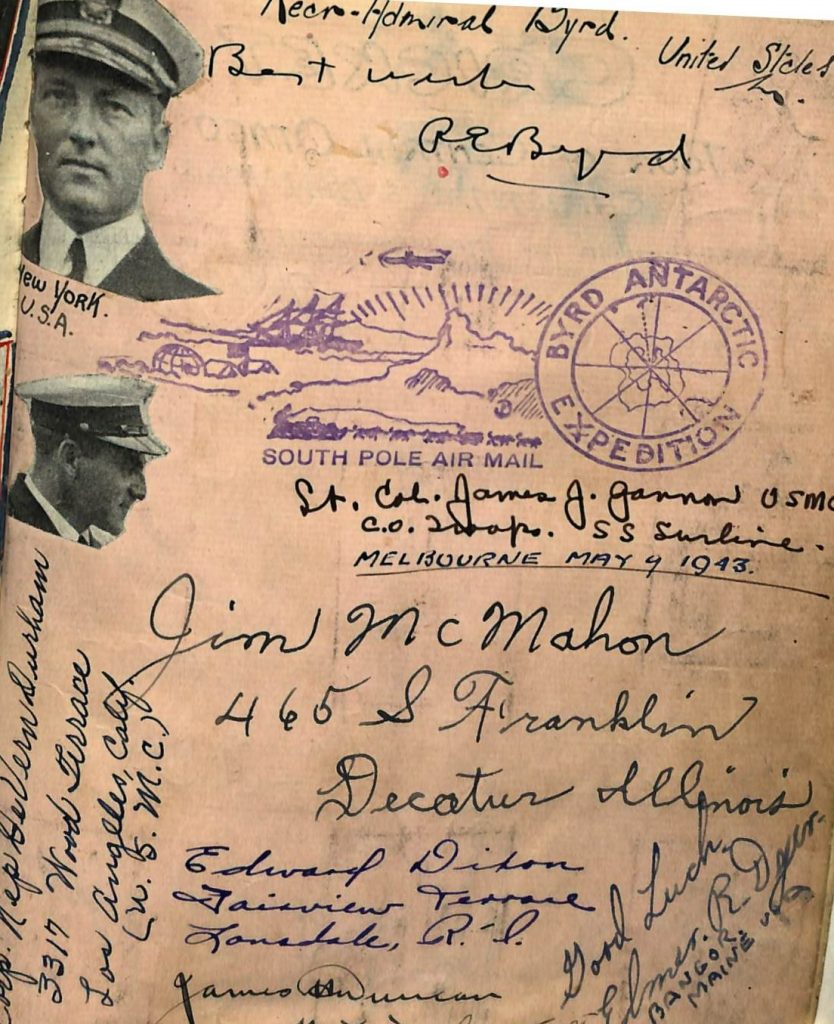

Jack’s album not only provides a glimpse of the sporting highlights of that period. He was also there on the spot when Byrd’s Antarctic Expedition set forth from Dunedin in 1930.

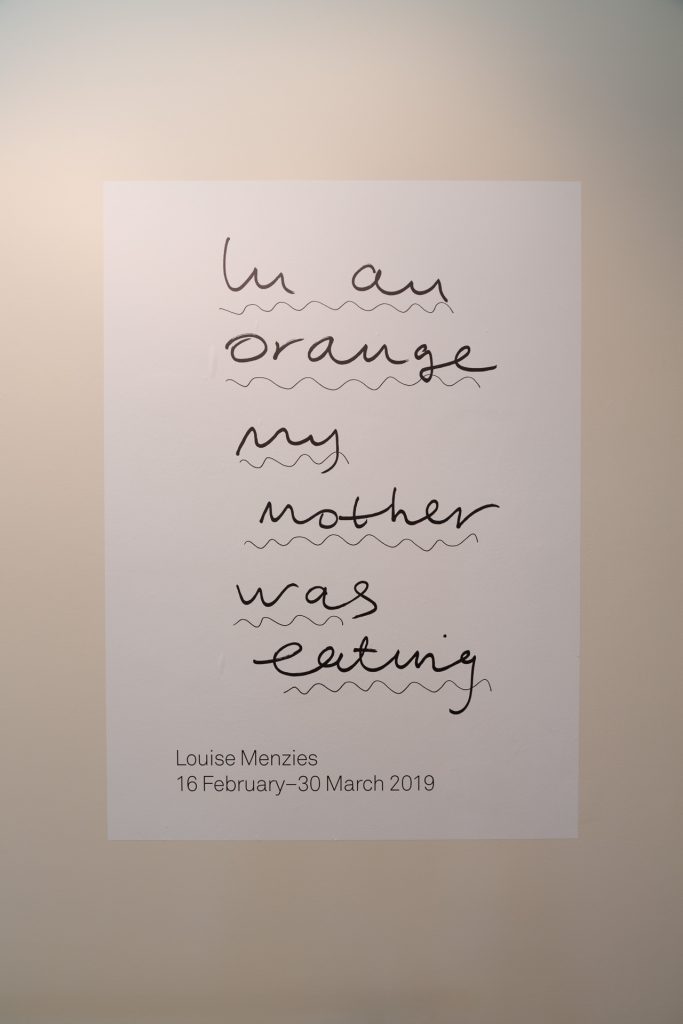

Finally, there’s one more autograph album that absolutely deserves a mention. It’s perhaps my personal favourite and dates back to that late Victorian period when young ladies – or at least those of upper/middle-class upbringing – had time for leisurely pursuits like autograph-collecting and an education that included skills in sketching and the use of watercolours.

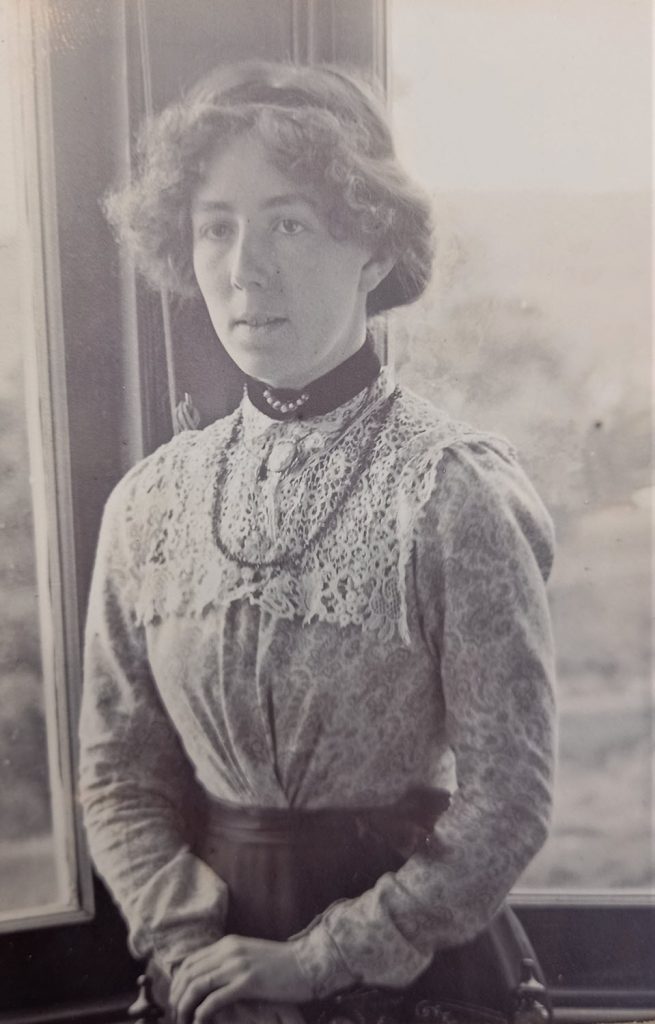

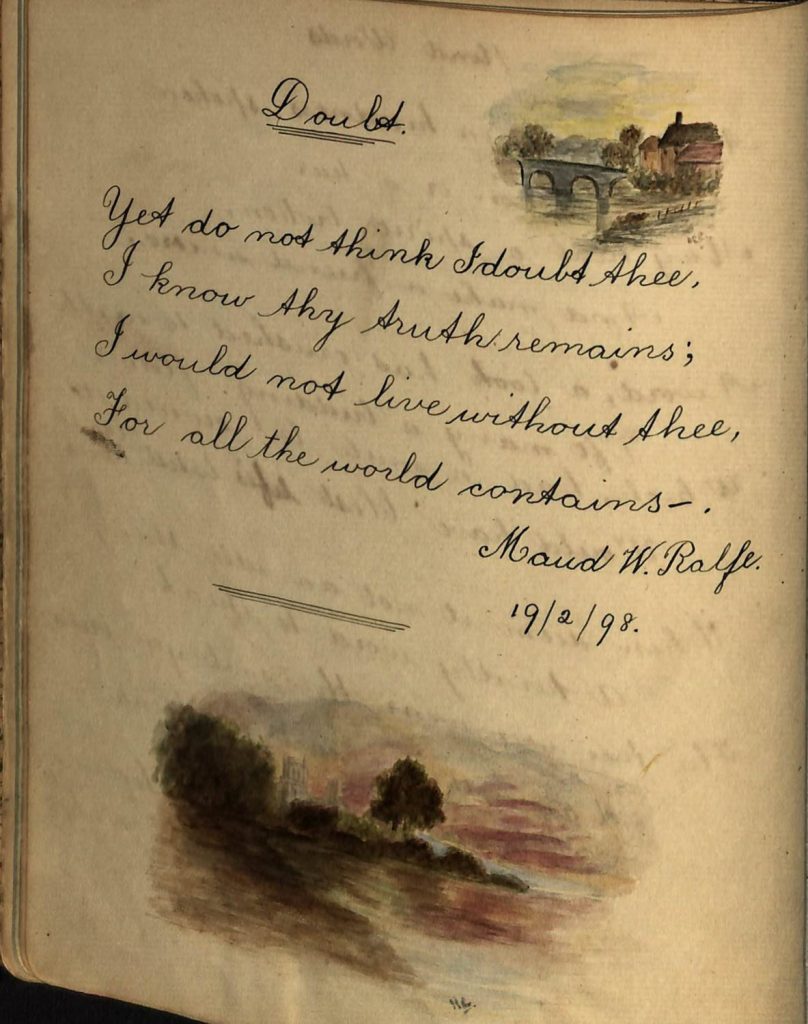

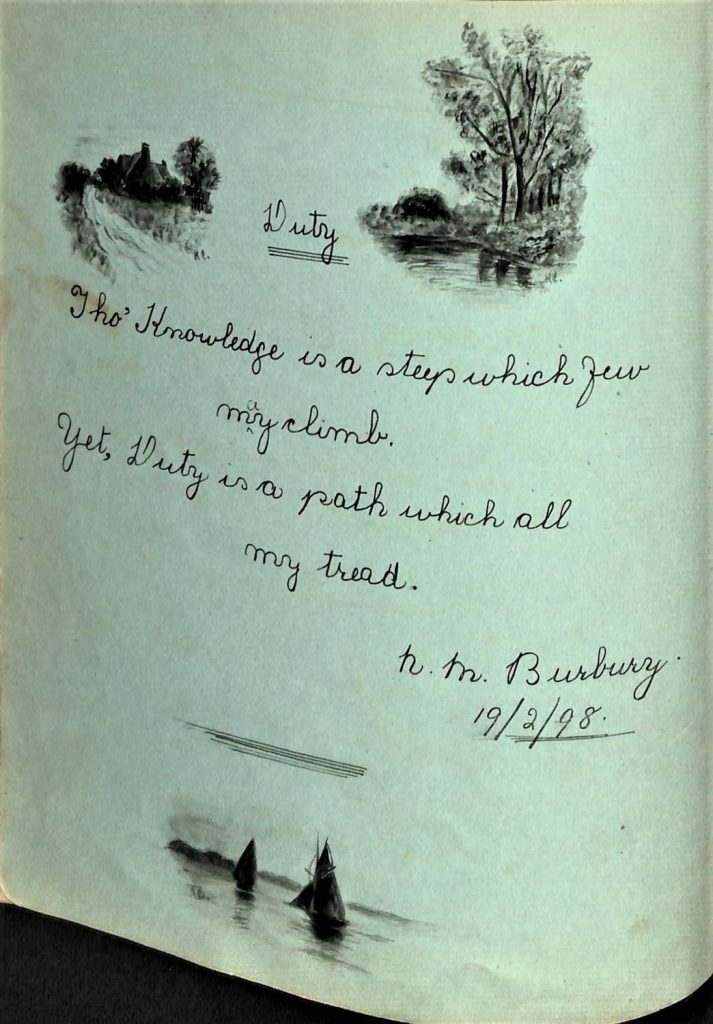

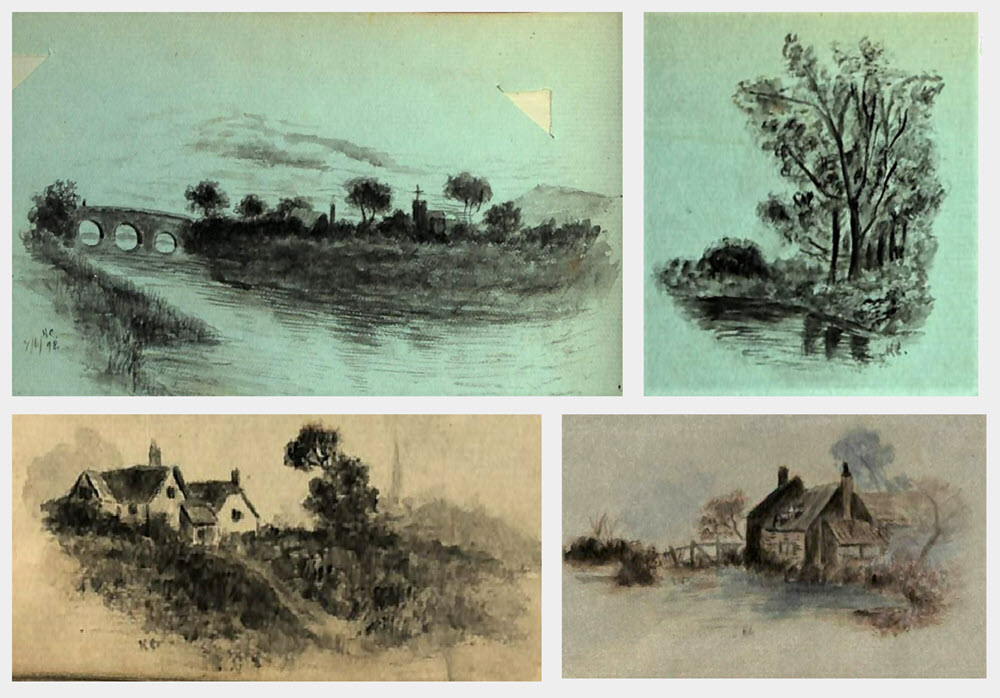

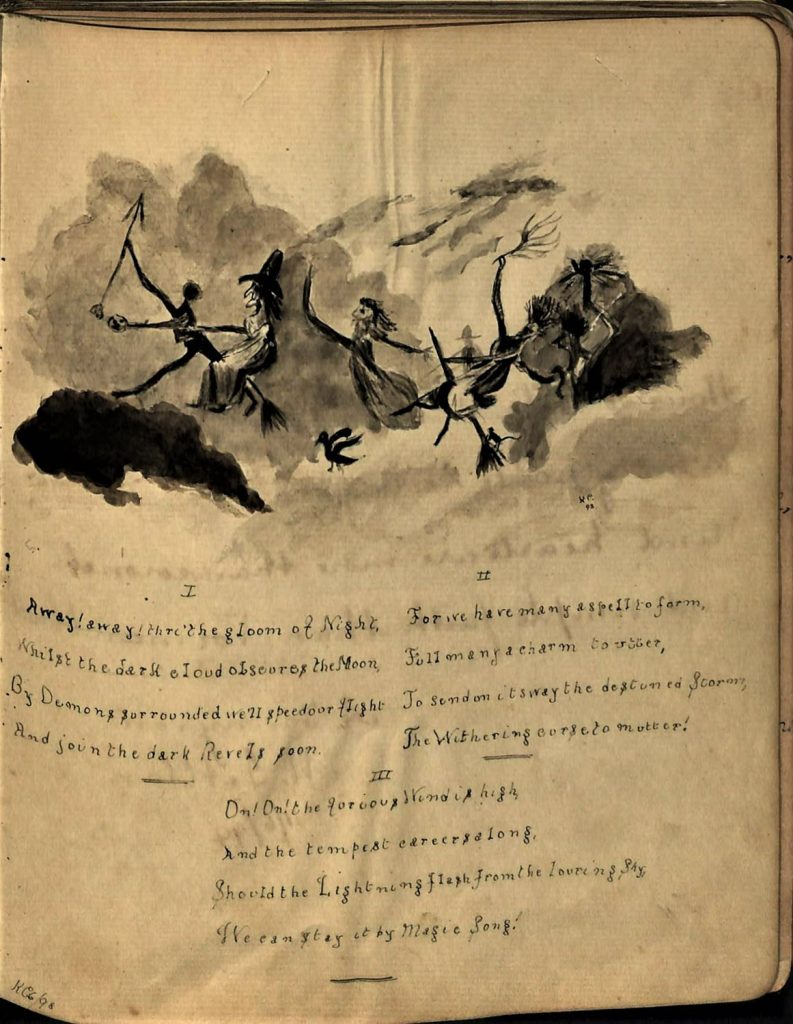

Kathleen Creagh was one such young woman. Born in Oamaru in 1882, she compiled her autograph album during her young adult years and, from the similar style of many of the sketches, seems to have illustrated many of the pages herself after collecting the autographs and thoughts of friends and family.

Take a closer look at the detail in some of Kathleen’s sketches. These illustrations are tiny – only a couple of centimetres square. It’s interesting to note they also have a somewhat ‘English’ feel to them, given that Kathleen herself was born and raised in Oamaru.

Not all Kathleen’s illustrations were romantic country scenes, however. A Halloween-esque verse shows she also had a keen sense of fun.

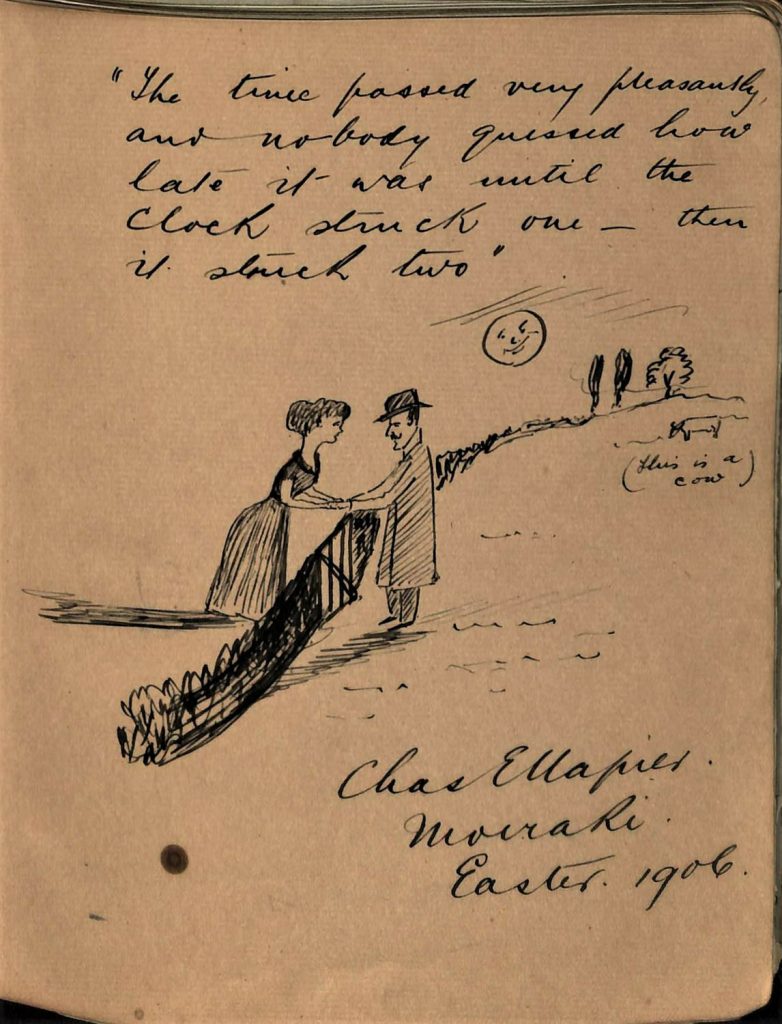

Kathleen went on to marry Charles Napier in 1906 and the couple had a daughter, Mary, who was also a talented artist. Mary Napier specialised in mosaics and worked as a theatre producer. She married sculptor John Middleditch and, in later years, donated both her mother’s autograph album and a Creagh family photograph album to the Hocken, along with papers relating to the Middleditchs themselves.

Charles Napier (2nd left) and Kathleen Creagh (on his right). Moeraki, 1906. Album 174 Creagh family : Portraits

So not only did Kathleen keep the autograph book of her youth for her own lifetime; it later became a treasured possession of her daughter, ultimately being entrusted to the care of Hocken. It illustrates a longevity in autograph books that far outlasts the modern-day postings made on Facebook.

Maybe it’s time to revive that autograph book tradition, so that others in the future can catch a glimpse of our own modern-day social lives. A Christmas stocking-stuffer perhaps?