Hands-On History

This week ten high school students from all around New Zealand took part in “Hands-On History” – part of the larger “Hands-On” programme that this year includes the Humanities Division and has drawn nearly 400 young people to Dunedin for a week of intensive learning and fun.

The History group have been based at Toitu Otago Settlers Museum, led by Dr Jane McCabe of the Department of History and Art History. The students have been learning about the ways that objects – the everyday and the extraordinary – help us to understand the connections between local and global histories.

Working in pairs, the students’ task over the week was to research and write about an object on display at Toitu, thinking about the role of the object in the gallery and locating information about the object – initially at Toitu, and then at the Hocken Collections with the expert assistance of Katherine Milburn. We also enjoyed an excellent introduction to the Central Library collections at the University of Otago with librarian Charlotte Brown.

The following pieces have been written by the students about these objects. As visitors to Dunedin, they have picked up lots of local history, as well as bringing a different perspective to Toitu’s collections. They have come up with some excellent insights!

A piece of the “Endeavour”: Encounters Gallery

In the Encounters Gallery, one of the first displays slightly hidden away in the corner has a rectangular piece of wood with copper tin attached to it by large flathead nails. This object was recovered from the wreck of an abandoned vessel, the Endeavour, more commonly known as New Zealand’s first recorded shipwreck.

The object displayed has obvious signs of wear and tear such as a slightly eroded wooden surface and rusting copper which has been bent out of shape. The object has clearly been cut into shape as there are no jagged edges. The physical appearance of the artefact communicates its age and conditions that the ship was subjected to through its long life. The placement of the object in the museum is significant because it is one of the earliest pieces dating back to the early 1790s and therefore it provides a link with some of the earliest European settlers.

The Endeavour, not to be confused with Captain Cook’s famous ship, was used to carry cattle and supplies, particularly sealing supplies. (Sealing is important in Otago’s history because the first European settlers that came to Otago were sealers, whalers and traders.) In 1795, the ship left Sydney for Norfolk Island, but after encountering a harsh storm on the journey on the Tasman Sea it ended up in Dusky Sound sometime between 5-12 October. The exact date is unknown as no diary was kept for that week. In Dusky Sound the vessel struck a rock. The ship was then declared unseaworthy by the captain, William Wright Bampton, and was stripped and abandoned. There were approximately 244 people onboard, including 45 stowaways. They all survived, but 36 were left in the area, living in the mountains for 18 months before returning to Sydney in 1797.

The shipwreck remained in Dusky Sound and scavengers continued to take pieces of wreck right into the twentieth century. Various pieces have ended up in museums around the South Island, where, as at Toitu, the artefacts are treasured and recognised as an important part of our history.

Stephanie Scobie and Jaymie Karena-Fryer

Gaelic Society Targe: New Edinburgh Gallery

This ceremonial shield was created for the Gaelic Society of New Zealand in 1881, as a symbol of their mission to defend the Gaelic language. The targe is constructed mostly of wood and leather, with a metal spike extending from the centre. It is embossed with Scottish thistles and the emblem of the Scottish national flag – the St Andrew’s Cross. The targe also has an inscription stating “Comunn Gharhealach, N.Z. 1881 Far Am Faigheadh Coigreach Baigh”, giving the date it was created as well as the society’s aim: “Far Shelter Foreigners’ Hospitality”. The targe, although created here in Dunedin, embodied the historic Scottish craftsmanship which arrived with the Scottish settlers.

The Gaelic Society was formed in Dunedin in 1881 to unite Scottish people. Its formation was met with unexpected success with over 400 Scots willing to become members. Traditionally the targe was used by clansmen in close combat as a shield, and also as stabbing tool. However, for the Society the targe was used for ceremonial purposes to show their commitment and determination to perpetuate the Gaelic language, literature, history, tradition of the Scottish highland, and to cultivate Highland music and dancing.

Over the years the Gaelic Society’s numbers declined. In 1976 the Society’s numbers were at only 65, and at 2006 it was officially dissolved. The targe found its way into the Toitu collection sometime before the 1990s. Its provenance is unknown. It is possible that it became redundant within the Society, but now it has become a prominent part of the New Edinburgh gallery at Toitu telling the story of original Scottish settlers.

Angeline Rolston and Kirby Rogers

Crinoline Cage: Material Culture Gallery

Would you ever consider wearing a cage if it was part of a fashion trend?

The crinoline cage is a popular bell-shaped petticoat that was widely worn under women’s skirts in the early 1840s through to the late 1860s. The once fashionable underskirt was first patented in the USA by W.S. Thompson in 1858 and was worn beneath women’s skirts to support the heaviness and fullness of their clothing, and to create a bell-shaped figure for the women of the Victorian era. The aim of the crinoline cage was also to decrease the size of the waist which was a huge trend in the 1800s.

In its “naked glory”, the crinoline cage was made of vertical bonds of tape with rows of either steel, whalebone or cane, and a pleated flounce. Thompson’s prize medal skirt has metal bands covered with tape held in place with tapes, eyelets and dates from the late 1850s to the early 1860s. The shape of the crinoline cage changed following their introduction. By 1865 they were much flatter at the front, but longer and more protruding at the back.

The crinoline cage was a vital component to women’s social status, and a worldwide fashion icon. The crinoline cage was widely worn in the UK and would have been imported into New Zealand; because of this very few survived. With this particular crinoline cage, the provenance is unknown.

Wherever they were worn, this “liberating device” (because it reduced the weight of petticoats) caused many accidents and were often quite hazardous. Their wearers were susceptible to being engulfed by fire – draughts from chimneys could attract the wide skirt and the air within fuelled with flames. Women were determined to wear then even though they were a hazard. Likewise, in Dunedin, renown for its muddy streets, this fashion was not a very practical way of dressing, yet because of social status and popularity women continued to wear Victorian outfits.

Visitors to Toitu can go back in time and experience Victorian costume by wearing a modern version of a crinoline cage, complete with full Victorian dress. Studying this object has made us aware of how trends have dramatically changed over time, and how strongly social status affected women’s desire – and determination – to follow fashion.

Kenya Akuhata-Brown and Keanalei Sapolu

Opium pipe: Dark Side of Dunedin Gallery

This opium pipe is located in a dark and hidden gallery that shows what life in “Devil’s Half Acre” (a central city slum in early Dunedin) was like; whereas just outside this gallery are shiny objects of the elite. This dark side is brought to life by sound effects in the gallery – bottles breaking, people fighting, and so on. This forms a contrast that shows how more wealthy Europeans had a totally different lifestyle than immigrants like Chinese.

The first twelve Chinese came to Otago from Victoria (Australia) to look for gold; they were invited by the Otago Provincial council. While they came here originally to earn money for their families in China, many ended up staying in Otago for the rest of their lives. When the gold ran out they moved towards the city which led to more encounters with local European society, and discrimination. Many Chinese used opium, which itself was a result of the British actions in China. When they came to New Zealand some Chinese brought this habit with them. But others developed this habit after coming to New Zealand due to many reasons such as loneliness and discrimination.

Because they used opium regularly others refused to accept them in society, and that led to more discrimination, so it became a neverending cycle. Opium was prohibited in 1901. But that was not the end of the problem; this meant that many Chinese had withdrawal symptoms which prevented them from working and functioning property. So this pipe is a symbol of that hardship, and this is why it is important to have it in the Otago Settlers Museum. It also helps us to think about what happens when people bring customs from their home country to a very different social context.

Prabhjot Kaur and Cindya Zhou

Radio valve: Technology Gallery

Radio is an internationally recognised form of communication and entertainment that now is just one of many kinds of media. The instant availability of the latest music or the latest news makes it hard to imagine what life was like without radio.

The valve is quite large – about the size of a water bottle – an intricate assembly of glass, metal and wire. It is a very fragile object, safely on display within a glass cabinet in the Technology gallery at Toitu. These valves were invented in France and used during the First World War, and were brought into New Zealand when some soldiers smuggled them into their jackets when returning from war.

In 1922, Dunedin’s Ralph Slade was able to receive radio signals from the USA, the first to do so in New Zealand. But this is not the only technological breakthrough Slade was to be a part of, no, he informed Frank Bell how to modify his radio set, which played a vital role in enabling the first round the world two-way radio contact between Frank Bell and a Mr Cecil Goyder in London on 18 October 1924.

The radio valve was one of many achievements for Frank Bell, who continued to break records in the distance for sending radio transmissions. So we can see that Dunedin was globally connected a century ago through advancements in this technology.

Stevie Courtney and Eniselika Ali

A Youthful Santa? Christmas in the Colonies

A couple of days ago my five year old niece asked me if it was winter – an easy mistake to make in the unsettled early weeks of Dunedin summer. When I corrected her, she replied confidently, “but it’s going to snow at Christmas – it always snows at Christmas!”

It’s not surprising that children in this part of the world might get confused about the impending arrival of the snowy scenes that surround us at this time of year. But what may be surprising to learn, is that the transfer of Christmas traditions from the old world to the new was a slow and uneven process. As Dr Ali Clarke pointed out in her recent Global Dunedin lecture, religious festivals provide a window into cultural encounters in New Zealand – not just between British settlers and tangata whenua, but amongst the new settlers too. Dunedin, with its mixed population of Scots and English, is an excellent location to note the marked difference in their observance of Christmas.

This reflected changes after the Reformation in England, when Protestants trimmed festivals. The Anglican calendar centred on events in the life of Jesus, while Presbyterians did away with all festivals, focusing instead on the week and the significance of the Sabbath. So in England, Christmas was an important holiday; while in Scotland, it was an ordinary working day. The Scots shifted their main celebrations to New Year, which was not a holiday in England.

In early Dunedin, the large number of Scots arriving from 1848 continued this tradition of working on Christmas Day. In the town, Anglican influence was soon felt, however, and it became a business holiday. But farmers of Scottish origin continued to ignore Christmas until the turn of the century. As the Scots did begin to embrace this celebration, it was more about food and family than religion. Throughout the colony, new traditions developed to celebrate a summer yuletide. Strawberries and cream joined Christmas pudding as a favourite dessert, and harvesting home grown vegetables (such as potatoes and peas) in time for the big day became an important part of festive preparations.

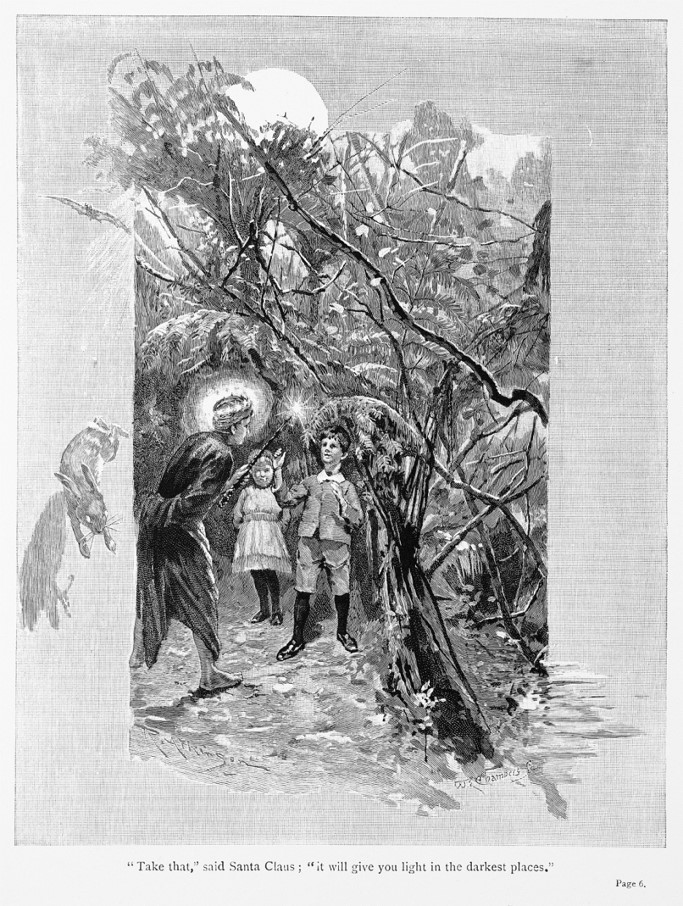

“Take that”, said Santa Claus; “it will give you light in the darkest places.”

Kate McCosh Clark, A Southern Cross Fairytale, 1891.

Source: http://www.childrenslibrary.org/

But what about the children? Did Santa’s sleigh jingle all the way to New Zealand? In 1891, Kate McCosh Clark, a former resident of Auckland then living in Britain, wrote A Southern Cross Fairy Tale. The story was for colonial children, “to whom snow at Christmas is unknown”, as well as youngsters in the “older land” who wanted to know what Christmas was like for their kin on the other side of the world. McCosh Clark set the scene with poetic descriptions of the local environment:

“It’s Christmas Eve and the long soft shadows of a summer night are quickly falling… No sound of joyous bells is borne upon the air… only the Bell-bird’s chimes from the bush, and the distant cow-bell’s tinkle mid the shadowy Manuka clumps.”

As the story went, the two children of the house were woken by a voice at midnight, exclaiming, “Wake up little ones!” There stood “a lad with a smiling face” and a bag of gifts.

Hal asked, “Are you a fairy?”

“No”, the lad proclaimed, “I am only Santa Claus”.

“Why, I thought Santa Claus was an old man”, said Hal.

“So I am, in the Old World”, replied he, “but here, in the New World, I am young like it.”

Hal, understandably, had immediate concerns about this proposition. Where were the reindeer, and the sleigh? How would his stocking be filled with gifts? In lieu of these traditions, the youthful Santa treated them to an enchanted tour of natural wonders, singing glow worms, gnomes and fairies, tuis and tuataras.

As it turned out, colonial children were to have their exotic new world and be visited by Santa Claus. In Dunedin from the turn of the century, children could visit magic caves and grottos in department stores like DIC, and in the arrival of Santa we might see the origins of the Santa parade. Direct from the South Pole, Santa emerged from the railway station and made his way through the town.

So when you are visiting Pixie Town, enjoying a Christmas barbeque, or queuing at the market for strawberries – take a moment to reflect on the way that our English, Scottish, and other cultural heritage has affected the way we celebrate (or not!) our mid-summer Christmas. Happy holidays!

Jane McCabe

References

Ali Clarke, Holiday Seasons: Christmas, New Year and Easter in nineteenth century New Zealand. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2007.

“Important Notice”, Evening Star, 17 December 1904, p.6

Kate McCosh Clark, A Southern Cross Fairy Tale, UK, 1891. Accessed at http://www.childrenslibrary.org/

“A Southern Cross Fairy Tale”, Auckland Star, 19 December 1890, p.3

See Ali Clarke’s Toitu lecture at her blog: http://clarkesquill.com/

Lopchu: A Tea Family in Dunedin

Why might this box of ‘Lopchu’ tea – found in a Dunedin kitchen cupboard a few months ago – cause a historian of the Kalimpong scheme to get very excited?

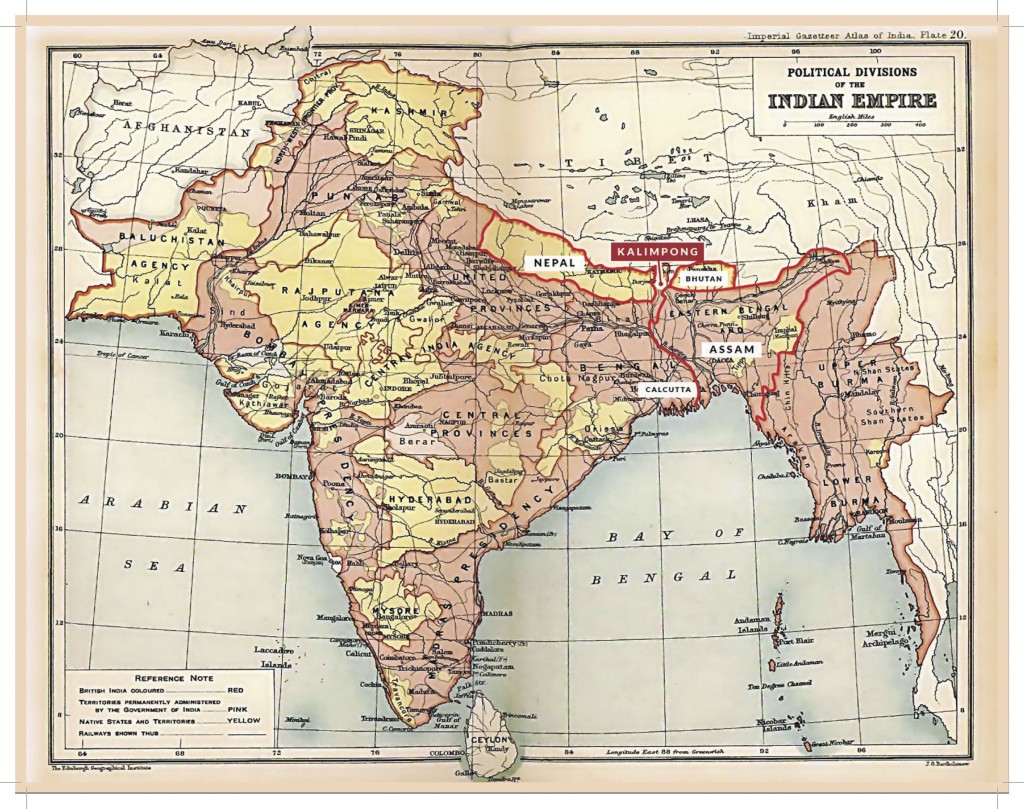

In the last blog we learnt about a Presbyterian scheme that arranged for the resettlement of adolescent Anglo-Indians in Dunedin in the early 20th century. Those migrants all grew up in a residential school in Kalimpong, in Northeast India.

But where were they originally from?

Exploring the life story of one of those migrants allows us to understand the larger drivers of the Kalimpong scheme, and the extraordinary trajectories of families caught up in the expansion of the British Empire and development of the tea industry.

George Langmore’s childhood was typical of the ‘Kalimpong Kids’ who were sent to Dunedin. Born on a tea plantation in Darjeeling to a British tea planter and a Nepali tea worker, for the first few years of his life George occupied the privileged but relatively free life of the planter’s child on a large estate – living in the bungalow, cared for by his mother and an ayah (Indian nanny), mixing with the various ethnic groups who worked on the plantation, and likely picking up several languages along the way.

As idyllic as it may sound to us today, this kind of childhood would have caused considerable concern to his father. Interacting with local workers, speaking local languages, roaming around the crops and ‘jungle’, and befriending children on the plantation – these were all seen as a threat to British children’s racial status. While it is tempting to be critical of the tea planters’ actions in sending their children away from the plantation, the letters written by these men to staff of the Homes have revealed their affection for their children and difficulty in parting with them.

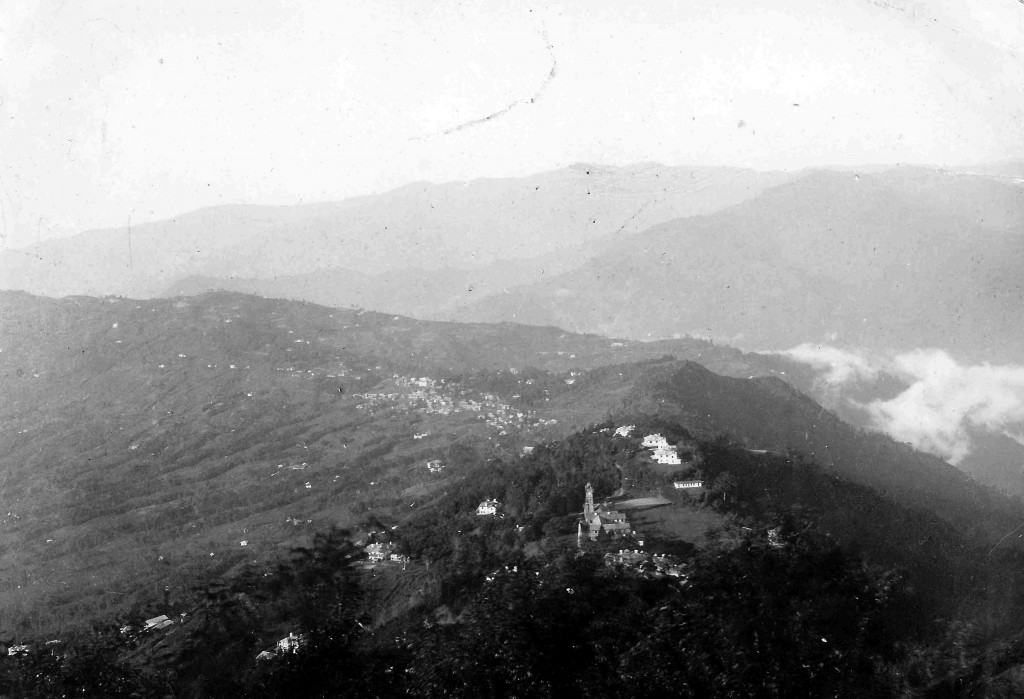

George was sent to the Homes in Kalimpong in 1903, when he was eight years old, and there he stayed until his arrival in Dunedin with a small group in 1911. Like all of the boys from Kalimpong he was placed on a local farm. George later secured work as an attendant at Seacliff, an asylum north of Dunedin, a position he held for more than twenty years. In 1918 George married Ellen Percy. He took Ellen to India in 1927, where they visited Kalimpong and the tea estate where he was born.

St Andrew’s Colonial Homes (foreground) and Kalimpong township (background). Photograph taken by George Langmore in 1927, and kindly supplied by the Langmore family.

George and Ellen had two daughters, and settled in Musselburgh. In 1937 John Graham, founder of the Homes, visited New Zealand with the aim of meeting again all of his graduates living there. For his week in Dunedin he stayed with George, who took him around the city to find the various graduates living here.

Graham wrote in his diary that George ‘must have done well’, noting two features of the Langmore home that attested to George’s global heritage: the fine carpets in the house were from Glasgow, and there was a sign on the gate that said ‘Lopchu Villa’. Lopchu was the name of his father’s tea estate in Darjeeling.

In their later years, many Kalimpong emigrants were reluctant to talk about their Indian heritage. But they have left clues that descendants have followed, often all the way back to Kalimpong and the tea plantations of Assam and Darjeeling.

George Langmore was relatively open about his connections to India. His descendants remember his love of cooking Indian food, and his unwillingness to settle for an ordinary cup of tea – he sourced tea (and pickles!) from India, mixing together a blend of different teas to get a ‘good cuppa’.

Beneath these quiet connections to their places of birth, the Kalimpong emigrants have held close their stories of separation from their imperial families. Archival research has enabled many descendants to reconnect with relatives in Britain, but there is little chance of tracing the maternal line of these tea plantation families.

Jane McCabe

References

http://kalimpongkids.org.nz/

Diary of John Graham, 1937, Kalimpong Papers, National Library of Scotland.

Iris McFarlane, Daughters of the Empire. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Roy Moxham, Tea: Addiction, Exploitation and Empire. New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, 2003.

Special thanks to the Langmore family for providing photographs and biographical details for George Langmore.

Finding India in Dunedin

How much do we really know about our multi-cultural origins?

As access to digital technologies and international travel to all parts of the globe continues to expand, researchers are uncovering pockets of unexpected cultural diversity in Dunedin’s early history.

A good example is the Presbyterian scheme that arranged for the resettlement of Anglo-Indian adolescents from Kalimpong to Dunedin in the early 20th century.

These migrants were the children of British tea planters and local women workers in Assam in northeast India. By the late 19th century, interracial mixing in British India was regarded as socially unacceptable. The isolation of Assam plantations meant that planters could continue to cohabit with local women, but what was to become of their children? Sending them ‘home’ (to Britain) for an education was out of the question.

The connection to Dunedin began with a Presbyterian Scot, Dr John Graham. Graham was a missionary in Kalimpong, a hillstation in the Darjeeling district. On his visits to planters, he often noticed mixed-race children being ushered into the back of their bungalows. In 1900, he secured a large area of land above the township of Kalimpong, and opened St Andrew’s Colonial Homes. His grand vision was to raise and educate tea planters’ children at the Homes and send them to the settler colonies when they reached working age.

Graham saw this as a solution that worked for the greater imperial good: settler colonies could help to resolve the Anglo-Indian ‘problem’ in India, and in return they received robust workers to fill labour shortages in lower status jobs like farm work and domestic service. It is easy to forget how strongly New Zealand and India were connected within the framework of the British Empire.

An article in the St Andrew’s Colonial Homes magazine, in January 1908, announced the departure of the first two graduates of the scheme from Kalimpong to Dunedin:

BEGINNING LIFE’S BATTLE

Our big boys are beginning to leave us and take their places in the world. Two fine lads sailed in the beginning of December to become COLONISTS in New Zealand… Miss Ponder of Waitahuna, Dunedin, is kindly arranging for their settlement.

The Reverend James Ponder and his sister were stationed at Waitahuna. Like Graham, James Ponder was a Scot, educated at Edinburgh University and experienced in overseas missionary work. His brother worked with Graham in Kalimpong. Ponder’s location, in a thriving rural community in South Otago, meant he was ideally placed to assist the Homes scheme by finding placements for the boys with local Presbyterian farming families.

In 1909 Graham visited Dunedin, to check on the first four male emigrants and to bring with him the first young woman to be placed in a Dunedin household. He met local Presbyterian reformers like Rutherford Waddell, and in an interview with the Otago Witness spoke enthusiastically about the development of the young colony. “Dunedin seems very homelike to me’, he stated. “As a Scot I delight to hear the good old accent.”

Graham returned to Kalimpong much encouraged, and set about regularly sending small groups to Dunedin. Between 1908 and 1920, 59 Kalimpong graduates landed at Port Chalmers and settled locally. In 1920, the scheme shifted northwards. Another 71 migrants landed in Wellington before the New Zealand government stopped granting permits to groups from Kalimpong in 1938.

This story of migration from Kalimpong connects Dunedin to the wider imperial and global circuit of missionaries and the development of the tea industry. The question of the migrants’ integration into the social fabric of Dunedin – and subsequent silence about their Indian heritage – will be addressed in the next blog through the story of one Kalimpong family.

Jane McCabe

References:

Jane McCabe, “Kalimpong Kids: The Lives and Labours of Anglo-Indian Adolescents Resettled in New Zealand between 1908 and 1938”. PhD dissertation, University of Otago, 2014.

James R. Minto, Graham of Kalimpong, Edinburgh: William Blackwood, 1974.

“The Land of the Sahib”, Otago Witness, 1 September 1909.

Gold-Dredges: From Dunedin to Siberia

Toitū Otago Settlers Museum holds the relic of an industry that

put Dunedin engineering on the world map

Gold-dredging was a New Zealand phenomenon. As early as 1863, during the alluvial gold boom, miner Charles Nicholson had invented a spoon dredge to lift gold-bearing gravel from the Molyneux (now Clutha) River, and later formed the first dredging company to try, albeit unsuccessfully, to exploit the resource. Attempts at building pneumatic dredges, diving bells and submarines then followed, all with little success. The man who would revolutionise this fledgling industry arrived in Dunedin, via the Victorian and Californian goldfields, from the upper Panyu district of Guandong, in southern China.

In popular memory, Chinese gold-seekers are largely remembered as fossickers and small-scale prospectors, reworking the fields that European diggers had worked through quickly. The entrepreneur Choie (Charles) Sew Hoy was not a fossicker: he was a key figure in the development of colonial Otago, an influential merchant and money-man, and a gold-dredging pioneer. In 1887 he acquired rights to a sizeable block at Big Beach, a gold-bearing flat on the Shotover River. He formed the Shotover Big Beach Gold Mining Company the following year with the intention to dredge the waterlogged deeper layers of his new claim. After watching the Dunedin harbour dredge at work he ordered one of a similar type, adapted by local engineering firm Messrs Kincaid & McQueen, to work the river flat as well as the bed. By 1889 the Sew Hoy Dredge was producing remarkable returns, generating up to £40 for a day’s dredging.

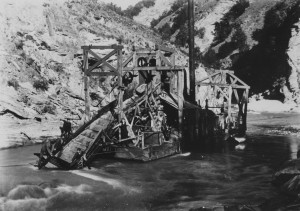

The Sew Hoy dredge at work, slightly askew after re-floating. “Sew Hoy dredge, refloated by J. F. Kitto no1”, S15-035a, c/nE4616/36, Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago.

Its success triggered a rush to peg claims up and down the rivers of Central Otago, attracting entrepreneurs and investors then gripped by the worst economic depression the province had known. It was the genesis of Otago’s first gold dredging boom, lasting from 1889 to 1891. By the end of 1889, Sew Hoy’s company was joined by sixteen other gold-dredging interests, and another twelve followed in 1890. Sew Hoy’s venture not only established dredging as a commercially viable strategy for gold mining, but also initiated some of the innovations that have led New Zealand engineers to acquiring world wide recognition. During the 1890s, Sew Hoy’s prototype design was refined, redeveloped and the size and capacity of the machines increased. Within a few years these continuing improvements gave Otago’s dredge operators the most sophisticated machines in the world, and as they became more standardised in construction, they were collectively, and proudly, known as “The New Zealand Dredge”.

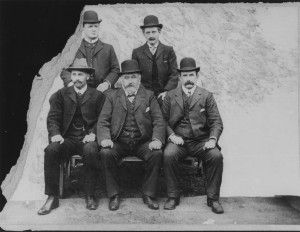

The faces of enterprise. A & T Burt’s board of directors bear all the obvious signs of success. Toitū’s dredge bucket was built by the firm – a testament to the lasting achievements of Dunedin engineering. “Dunedin: A & T Burt- Directors, head office”, S15-035g, c/nE3762/15, Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago. Commentary: Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago.

The experiments, discoveries and experience of dredging in greater Otago established Dunedin as the world’s leading centre for dredge design and construction. In September 1899 there were 40 dredges, each costing between £3000 and £10000, at various stages of construction between the firms of Kincaid and McQueen, Cutten Bros., R. S. Sparrow and Co., Cossens and Black, the New Zealand Engineering and Electrical Co., Morgan & Cable and A. & T. Burt, which laboured day and night to complete their orders. The pressure on local foundries and firms that year was such that contracts were even sent offshore to Australia and Great Britain! Russia, Siberia, British Burma, Malaysia, the Gold Coast of Africa, South America and Australia are among the destinations of Dunedin’s famous designs. As early as 1898, Messrs Cutten Bros. of Dunedin received their first order from Siberia for the design, construction and erection of three dredges, customized for local conditions. By 1900 there were 228 dredges working in Otago and Southland. As the vast majority of these were designed and constructed locally, Dunedin benefitted not only from the reputation, but the revenue: the industry pulled the province from the shadow of the 1880s depression, slashing unemployment and contributing to the growth of industry and communications. Ultimately, Choie Sew Hoy’s successful venture and the innovations it was to inspire won Otago about one third of its total gold production.

A timeline in dredge buckets. Note the pronounced increase in bucket size between 1886 and 1895, (Sew Hoy’s first successful year was 1889). “Dredge Buckets, the present and the past”, S05-165i, Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago.

So while Toitū’s dredge bucket may seem to a humble or mundane object on first sight, its influence has been profound and stands at a centre of an important set of global connections that shaped our city.

Violeta Gilabert

References:

Grant, David Malcolm. Bulls, Bears and Elephants: A History of the New Zealand Stock Exchange, Wellington, N.Z.: Victoria University Press, 1997.

Ng, James. “Sew Hoy, Charles”, from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara- the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 30 October 2012, URL: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/biographies/2s14/sew-hoy-charles

Smith, Philippa Mein. A Concise History of New Zealand. New York, U.S.A.: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

“The History of the Design and Construction of Gold Dredges in New Zealand”, IPENZ, URL: https://www.ipenz.org.nz/heritage/documents/ , retrieved 22.12.2014.

Walrond, Carl. “Gold and Gold Mining- Dredging”, Te Ara- the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 13.7.2012, URL: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/gold-and-gold-mining/page-8.

The Carisbrook Crusade

Superstar evangelist Dr. Billy Graham electrifies Dunedin in 1969

Carisbrook, 9 March 1969: Under a threatening clouds, twenty thousand spectators brace against the cold wind, wrapped in blankets and travelling rugs. Many have come from beyond Dunedin, by bus from smaller regional centres and still more by train from Invercargill and Christchurch. A group of Canadians and Americans, as well as a party from the North Island arrived by air earlier in the week. Present also is the minister of broadcasting, the Hon. L. R. Adams-Schneider and mayor of Dunedin Mr. J. G. Barnes. At this point, the event might be fairly mistaken for a big rugby match, save for the fact that rugby games never end with over one thousand people, eighty percent aged under twenty-five, publicly coming forward to accept Christ. This was the first and last Dunedin crusade of American evangelist Dr. Billy Graham.

Looking down on Bill Graham at the ‘Brook. J.D. Douglas, “A Tale of Two Islands,” Decision, May 1969, 8, in Roy Nelson McKenzie, “Billy Graham Crusade Newsletters 1967-1969”, 2012/18/6, DE 7/5, The Presbyterian Research Centre (PCANZ), Knox College, Dunedin.

Dr Graham’s career as an international evangelist stretched back to the mid 1940s, where his rousing speech and commanding personality transformed the humble open-air sermon into phenomenally successful mass rallies. A decade before his visit in the flesh, Graham had reached out to Dunedin via landline: his 1959 crusades in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch were relayed in real time to crowded meetings in urban and rural centres around the country, reaching over 185,000 New Zealanders in addition to the tens of thousands who personally attended his rallies. Having conducted major crusades throughout Africa, Europe, Britain, South America, Asia and the United States, by the time he personally appeared at Carisbrook a decade later, Graham was the world’s best-known evangelist.

Dr Billy Graham and his crusade team arrive aboard the “Gospel Train” at Caversham station. J.D. Douglas, “A Tale of Two Islands,” Decision, May 1969, 8 in Roy Nelson McKenzie, “Billy Graham Crusade Newsletters 1967-1969”, 2012/18/6, DE 7/5, The Presbyterian Research Centre (PCANZ), Knox College, Dunedin.

Evangelical Protestantism in New Zealand was, in turn, part of a worldwide movement that took hold in the post-war years, breathing new life into a tradition inherited from 1730s Britain by her colonies. From 1949, Billy Graham was a unifying figure in this modern movement that was built on the long-standing evangelical emphasis on justification by faith and in the primacy of the Bible. Earlier in the century Dunedin had seen the mass missions of R.A. Torrey and J. Wilbur Chapman: pre-campaign preparation, prayer meetings, the kindling of emotion with large choirs and audience participation, calculated build ups of tension, public affirmations and “follow ups” through counselling or decision cards were all well-established tactics. However, revival methods took on a new flavour in the late fifties and sixties as popular culture and mass entertainment established the compelling power of celebrity status, the exploitation of new travel networks and a mastery of modern technology as central elements of the crusade arsenal.

A rush forward. New converts join counsellors at the conclusion of the crusade – signing decision cards, receiving bible study booklets and giving their names to local church representatives. J.D. Douglas, “A Tale of Two Islands,” Decision, May 1969, 9 in Roy Nelson McKenzie, “Billy Graham Crusade Newsletters 1967-1969”, 2012/18/6, DE 7/5, The Presbyterian Research Centre (PCANZ), Knox College, Dunedin.

International air travel enabled Graham and his crusade team to conduct 419 crusades in 185 countries and territories over the course of his 58-year career. He preached before 84 million people, and reached an additional 215 million via radio, television and landline relay. While Dunedin missed out on the full impact of Graham’s presence in 1959, landline relay meetings were still successful in bring his message to Otago. New Zealanders like the rest of the world, were becoming accustomed to experiencing from afar via the latest technologies. A branch of Graham’s association, World Wide Pictures, produced impressive, full-length feature films such as “Souls in Conflict” (1954) and “For Pete’s Sake” (1969), which were used alongside footage from previous campaigns as to build interest for the crusade. These “commendable instruments of evangelism” were a hit in Dunedin: in just three screenings at His Majesty’s Theatre, Souls in Conflict was seen by 3,600 people, including many from out of town. Audiences would begin arriving up to an hour and a half before the screenings to secure a seat and many were turned away. This was 1956, over a decade before Graham’s visit and a sure sign of things to come.

However, modernity also brought worries: the Cold War, materialism, the sexualised threat of rock n’ roll, disintegration of families and a plague of foul-mouthed bodgies and widgies filling the country’s milk bars gave Graham’s message tremendous currency. To Dunedin audiences, he emphasised that the world would face catastrophe if morality was allowed to fall by the wayside, despite the technological wonders of the new age. The answer lay in Christian rebirth and devoted service to the Lord, which Graham invited his audience to undertake by stepping forward after the sermon and giving their name to one of the 600 counsellors waiting in front of the official dais. The involvement of local ministers, the Crusade Choir & solo singing by George Beverly Shea softened the gravity of Graham’s message.

The logic behind this approach had been explained to a meeting of minsters and theological students at Knox college the previous afternoon: “To communicate the gospel there must be a contagious excitement about Christ. There is little feeling in the church, it is too cold, too hard, too logical- emotion is an essential part of a crusade”. Graham’s newfangled methods, his emphasis on the power of the emotions, the universal applicability of the gospel, and the requirement for an individualistic decision to become a Christian retained a heavy presence in New Zealand ministry from the late 1950s to the 1960s, contributing to the growth of evangelical style parishes around the country. Though brief, the Carisbrook Crusade lingered in local memory for years to come – placing evangelical innovation and energy squarely in the public eye, and reflecting an undeniable drift towards new forms of Christianity in Dunedin and throughout the Western World.

Violeta Gilabert

Sources:

“Billy Graham Crusade Newsletters 1967-1969”, 2012/18/6, DE 7/5, The Presbyterian Research Centre (PCANZ), Dunedin.

Bryan D. Gilling, “‘Back to the Simplicities of Religion’: The 1959 Billy Graham Crusade in New Zealand and its Precursors.” Journal of Religious History, Vol. 17, No. 2, December 1992.

Stuart M. Lange, A Rising Tide: Evangelical Christianity in New Zealand, 1930-1965. (Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2013).

Judith Smart, “The Evangelist as Star: The Billy Graham Crusade in Australia 1959”, Journal of Popular Culture, June 1999.

The Persistent Pioneer

Who made a home for the “magical new technology” of cinema in Dunedin? Look no further than Henry Charles Gore.

Long before New Zealand’s latest boom of big-ticket features there is a little known history of local film-making that stretches back to the early twentieth century. Dunedin cinema enthusiasts were extensively involved in fostering this culture which, fuelled by the marvellous nature of the medium, flourished here.

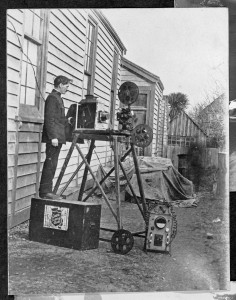

Another of Dunedin’s cinematic pioneers, Major Joseph Perry of the Salvation Army. Perry was posted to Melbourne at the age of 19 where he joined the Limelight Department- dedicated to spreading the word of the Lord through the technological wonders of the new visual medium. In 1898 led the Limelight New Zealand tour, returning to Dunedin with fourteen one-minute short films and an orchestra in tow. “Member of the Salvation Army, possibly Joseph Perry, by a film projector.” Ref 1/2-125505-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. URL: http:// natlib.govt.nz/records/22899176.

The general emergence of cinema as a global form of mass entertainment was related to widespread social transformations that occurred at the end of the nineteenth century. The “movie” found its home in the habits of a faster paced city life, being cheaper, shorter and more spectacular than say, magic lantern shows or vaudeville productions. Modernity also brought new strength to old networks of global distribution, as reflected in the astonishingly rapid arrival of moving picture technology in Dunedin; making its way from the Lumiere Brothers’ first international screening in Paris, 1895, to our southern city in the space of merely a year!

This pioneer screening was provided by Australian J. F. MacMahon’s Salon Cinematographe, the first of many travelling exhibitors to visit Dunedin in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Often with the assistance of live performers and small orchestras, these companies hired small venues, set up their projectors and enraptured crowds with the “newest electric marvel of the century”.

Outside the city, community facilities served as part-time suburban cinemas. The Green Island Municipal theatre hosted both theatre performances and film screenings from 1887. “Green Island Municipal Theatre, 1887-1960”, S08-101a, Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago.

Having witnessed said marvels, fourteen year-old Henry Charles Gore was determined to get a piece of the action. Being an avid amateur photographer, Gore opened his own independent photographic studio on King Edward Street at the tender age of eighteen. The following year he had imported the necessary motion picture equipment and filmed local events himself, following the example of other New Zealand pioneers: A. H. Whitehouse of Auckland, the first to import a camera to New Zealand (1898), and travelling exhibitor T. J. West of West’s Pictures. He mastered the workings of projectors and other cinematic technology, making his own cameras and arduously translating French or German instruction manuals. He began travelling internationally in 1904, eventually landing a job as a technician and operator of Simplex Projectors in a Hollywood studio – a position that introduced him to the latest technology in cinematic projection. In doing so, he became the first New Zealander to gain overseas film-making experience.

The resplendent Grand Picture Palace on Princes Street opened its doors in 1915. “The Grand Picture Palace 1915-1947”, S15-035d, c/nE2913/42, Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago

Returning to Dunedin, Gore married in 1910 and the first of his nine children was born the following year. He fuelled his love of film by documenting his family at play and on holiday; filling the front room of his St Clair home with cameras and developing equipment, which also hosted those who visited “Mr Gore” for technical advice in their own projects. When the Queen’s Theatre was opened in Auckland, 1911, Gore’s known expertise in cinematic technology landed him the role of chief projectionist. Returning to Dunedin in 1912, his extensive working knowledge and enthusiasm was instrumental bringing Dunedin its first permanent cinema halls, with the added bonus of providing Gore with a venue for his local shorts.

Photographed by H.C. Gore himself. Picture theatre orchestras were a cornerstone of the silent film era, providing atmosphere, emotion, and in some cases humour in any given screening. “Octagon Picture Theatre Orchestra 1923”, S15-035g, negE679/24, Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago.

As his business grew alongside his family, Jack Welsh was hired as a bag boy, assistant and veritable protege. Together, Welsh and Gore dominated local film production in Dunedin before World War II – capturing newsreels of local sporting or cultural events for local theatres, scenic and industrial films for general release Welsh would later go on to produce Dunedin’s first feature-length “talkies” in the 1930s. He and other producers of film and photography that subsequently followed in Gore’s path owed much to his persistence, passion and expertise. The man himself remained a mainstay of Dunedin’s cinema scene until his death in 1967, at the age of 85. Up until then, if ever a local projector broke down, the call went out: “Send a cab for Mr Gore!”

Violeta Gilabert

References

“Cinema”, from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, ed. A. H. McLintock, originally published 1966. Te Ara – the Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, updated 23.4.2009, retrieved 19.2.2015.

Pivac, Diane. “Dunedin’s First Film Maker: Henry Gore, 1882-1967”, Tracking Shots: Cast and Crew. Website Nga Taonga, New Zealand Film Archive, URL: www.ngataonga.org.nz/tracking-shots/cast-and-crew/Gore-Henry.html, retrieved 19.2.2015.

Price, Simon. “Persistent Pioneers: Early Film-Making in Otago & Southland, 1896-1939”, Ph.D. diss., Otago University, 1995, 3.

Connections: the Telegraph

100 years ago the Telegraph Office was Dunedin’s commercial nerve centre.

Every telegraph clerk learned his standard commercial codes in order both to abbreviate telegrams and to preserve the security of sensitive information. Telegraph Office, Dunedin. Williams, Edgar Richard, 1891-1983 :Negatives, lantern slides, stereographs, colour transparencies, monochrome prints, photographic ephemera. Ref: 1/1-025835-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22335890

Fast and efficient communication was a recurrent challenge for the inhabitants of Dunedin. However, the discovery of gold brought some 64,000 immigrants to the region between 1861 and 1863, fuelling an economic boom that not only prompted an expansion of commercial activity but also drove the emergence of a range of increasingly specialized enterprises. Accordingly outward mail from Otago increased 350% between 1860 and 1864, more than one quarter making its way to Victoria, where many miners had families or business interests.

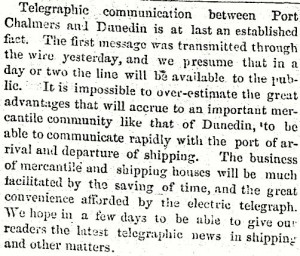

While hand-written letters remained vital in maintaining contact between individuals a day or more apart, the telegraph captured the popular imagination as the world’s first form of instant communication. After spreading rapidly around the world during the 1850s, the telegraph finally reached New Zealand in July of 1862 when Christchurch and Lyttleton were connected. In Dunedin, local business interests and newspapers had been agitating for speedy communication with Port Chalmers, the district’s main port of call, as well as with the goldfields in the hinterland. Thanks to the efforts of Julius Vogel and Provincial Superintendent James Macandrew, the line from Port Chalmers to Dunedin was established in August 1862, erected by a local firm Messrs Driver & Co.

Connected! The creation of the Port Chalmers-Dunedin telegraph line announced in the Otago Daily Times,16 August 1862, 4.

Dunedin’s first telegraph office, “a small cottage of a familiar type”, was established in Lower High Street and managed by Messrs. Driver & Maclean. The first government telegraph office was however, “nothing more nor less than a sentry box” situated between the Driver & Maclean’s office and the Custom House. Formerly this modest structure had been used to shelter the armed constables who guarded the gold deposited in the Customs building. It contained only enough elbow-room for one, requiring two of the three officers to wait on the footpath whenever a telegram was being transcribed. These Dunedin offices were nodes in a rapidly growing network, as telegraph lines were being extended to all the principal centres and, in turn, lines were quickly reaching out into the hinterland from these major site of settlement. The first Cook Strait cable, a crucial link in the entire system, was laid in August 27, 1866. By the end of the decade the South Island was comprehensively linked by telegraph.

Humble beginnings. A sketch by J.E Green shows Dunedin’s first telegraph facilities, the “little sentry box” barely visible between customs house and the weatherboard office on the left. “Scrapbook of Newspaper Clippings…”, Variae V.35, S14-69a, 1928-1948, Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago.

Early in 1866 Dunedin’s sentry box was superseded by a larger weatherboard shed on the corner of Bond Street, which was then on the waterfront. Ngāi Tahu fishermen drove a brisk trade selling barracouta and other fish caught from the Heads, pulling their canoes up onto the beach and conducting business through the office windows!

Although it was later superseded by a grand building in 1877, Dunedin’s humble weatherboard telegraph office was, in fact, a key site in New Zealand’s first “hacking” scandal. This was initiated by the arrival of news in October 1870 that Napoleon was imprisoned in Germany and that France had been declared a republic. For Dunedin’s European-born population these were momentous developments as detailed by the Otago Daily Times: “a greater degree of excitement [had] never been witnessed in Dunedin… a crowd of two or three hundred literally besieged our doors, waiting for three or four hours at least until the telegrams were published”.

In 1877 the Weatherboard office was demolished and a “more imposing edifice” erected in it’s place (far left). Fast and reliable communication facilitated massive commercial and industrial expansion in Dunedin, the results of which can be seen in the resplendent appearance of the office and the Royal Exchange Hotel to the right. S15-012a, “Dunedin, High Street”, [ca. 1890], messrs. F. Bradley & Co., c/nE2336/6, Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago.

Libel! ODT editor G.B. Barton protests against a tactical telegram delay, provoking the wrath of the government in a very public libel suit. The outlining was present in the scanned original of the newspaper, proof of its importance. The Otago Daily Times, 1 October 1870.

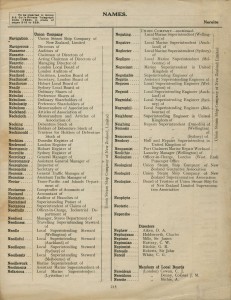

Political controversies aside, telegraph technology was seized upon by local firms such as Dalgety Ltd. and the Union Steam Ship Co., which developed their own private codes. Such enterprises flourished with the benefits of fast and reliable communication, and in turn, telegraph returns provided functioned as reliable barometers of economic growth. Figures throughout the 1860s and 70s confirmed Dunedin’s reputation as New Zealand’s commercial capital and they are a strong reminder of the long-standing connections between communications and commerce.

Confidentiality and Compression: Sparing expense and preserving commercial secrecy was the aim of the game. The Union Steam Ship Company’s elaborate 515 page telegraph code book did just that- condensing “Assistant General Manager of…” to “Necromancy” and “Auditor of Branches of…” to “Nectarine.” Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago.

Violeta Gilabert

References:

Walter, I. M., “Improvements in New Zealand’s Overseas Communications, 1866-1880, and their Relation to the Country’s Development”. M.A. diss., The University of Otago, 1969.

Wilson, A. C. “Telecommunications- Business and Cable Networks”, Te Ara- The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 13.07.2021, URL: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/telecommuncations/pate-3

Wilson, A. C. Wire & Wireless: A History of Telecommunications in New Zealand 1890-1987. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press, 1994.

Wilton, Dave. “The Great New Zealand Telegram Hacking Scandal (1871): A Shakespearian Comedy inMultiple Parts” in New Zealand History. URL: www.nzhistory.net.nz/files/documents/telegram-hacking-scandal.pdf, retrieved 12.1.2015

What About Captain Cook?

After our first blog post – on the arrival of the John Wickliffe at Kōpūtai/Port Chalmers in March 1848 – one of my students asked: ‘Why didn’t you start with Captain Cook?’ It is a good question and its answer helps explain the shape of the early history of Otago.

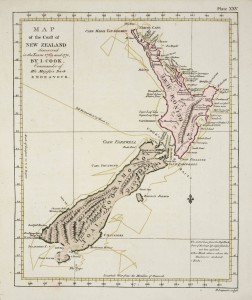

A 1773 rendering of the track of the Endeavour around New Zealand. Cook, James, 1728-1779. [Cook, James] 1728-1779: Map of the coast of the New Zealand discovered in the years 1769 and 1770, By I. Cook, Commander of His Majesty’s Bark Endeavour. B. Longmate sculpsit. [London, 1773]. Parkinson, Sydney, 1745-1771: A journal of a voyage to the South Seas, in his Majesty’s ship, ‘The Endeavour’. Faithfully transcribed from the papers of the late Sydney Parkinson. London, Printed for Stanfield Parkinson, the editor, 1773. Ref: PUBL-0037-25. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22751427

Altho we kept at no great distance from the shore yet the weather was so hazey that we could see nothing destinct upon the land only that there were a ridge of pretty high hills parallel with and but a little way from the sea-coast.

On Sunday 25 February, the Endeavour ran down the Otago coast, passing the entrance to Otago Harbour and travelling along the exposed Pacific coast of the Otago Peninsula. Cook was struck by the large headland that juts into the Pacific Ocean on the Peninsula’s east side, which he named Cape Saunders after Sir Charles Saunders, the Commander of the British Fleet when James Cook served in 1758-9 on the St Lawrence River (in what is now north-eastern Canada).

Cook noted the landscape feature that made the greatest impression on the Endeavour officers and crew: ‘there is a remarkable Saddle hill laying near the shore 3 or 4 Leagues SW of the Cape [Saunders]’. Lieutenant Zachary Hicks also recorded the prominence of ‘a remarkable saddle hill’, as did the able seaman Francis Wilkinson, the astronomer Charles Green, and the midshipman John Bootie. While there is no firm textual evidence to suggest that Cook formally named ‘Saddle Hill’, it is clear that this would be an obvious name for future incoming Europeans. Given recent debates over the significance and future of Saddle Hill it is important to note its centrality in the Endeavour accounts of coastal Otago.

As the Endeavour progressed down the Otago coast, two important questions loomed. The first of these was the extent and nature of the native population. As they tracked south from Cape Saunders, Cook noted that

Being not far from shore all this morning we had an opportunity of viewing the land pretty distinctly: it is of moderate height, full of hills which appear’d green and woody, but we saw not the least sign of Inhabitants.

Earlier, when the Endeavour was stalled off the north Otago coast, Joseph Banks reflected: ‘As we have now been 4 days upon nearly the same part of the coast without seing any signs of inhabitants I think there is no doubt that this part at least is without inhabitants.’ But further south, off the Catlins coast, Banks revised that opinion, as on 4 March

In the evening [the Endeavour] ran along shore but kept so far of that little could be seen; a large smoak was however, which at night shewd itself in an immence fire on the side of a hill which we supposd to be set on fire by the natives; for tho this is the only sign of people we have seen yet I think it must be an indisputable proof that there are inhabitants, tho probably very thinly scatterd over the face of this very large countrey.

Of course, had the Endeavour found the entry to Otago Harbour and perhaps explored the contours of the coast to the north closely and carefully in more favourable weather conditions, they would have seen and encountered Kāi Tahu Whānui settlements: the land was inhabited, used and valued.

The other important issue that those on board the Endeavour pondered was whether Te Wai Pounamu was an island or part of a large continental land mass. This was not simply a question of immediate cartographical significance, but was part of a larger imperial quest. The British Admiralty had issued Cook secret instructions to search for the as yet undiscovered great southern continent, Terra Australis Incognita.

Only a few on the Endeavour believed that Te Wai Pounamu was continental in size and even those who did believe it was a large landmass did not necessarily see it as Terra Australias Incognita. Off the Otago coast, Banks reflected in his journal:

We were now on board of two parties, one who wishd that the land in sight might, the other that it might not be a continent: myself have always been most firm for the former, tho sorry I am to say that in the ship my party is so small that I firmly beleive that there are no more heartily of it than myself and one poor midshipman…

Banks has been given hope in part because the high hills and distant mountains that were visible inland from north Otago’s coastal waters suggested that Te Wai Pounamu was a substantial land mass. As the sun had set on 23 February, the air had cleared affording a good view of Te Wai Pounamu’s interior. Cook’s journal recorded:

We saw the land more distincter than we had at any time before, extending from North to SWBS [southwest by south], the inland parts of which appear’d to be high and mountainous…

Māori at Queen Charlotte’s Sound had told Cook that he could circumnavigate Te Wai Pounamu in just four days. But the evidence now clearly showed that ‘this Country to be more extensive’. Off Waikawa, in the southern Catlins, Banks remained optimistic that the minority view would triumph, writing in his journal: ‘Land seen as far as South so our unbeleivers are almost inclind to think that Continental measures will at last prevail.’ Two days later on 8 March, as the Endeavour drifted slowly south, Banks admitted that those lands that he spied to the south were, in fact, ‘nothing but clouds’. The following day, as they neared South Cape, the ‘Continent mongers’ grew dejected as the seascape and landforms suggested that they had reached the southern extreme of Te Wai Pounamu. As they rounded South Cape and pushed west on the 10th of March, Banks recorded the ‘total demolition of our aerial fabrick calld continent’. Te Wai Pounamu was not the great southern continent and by the time they were in Fiordland Cook was aware that there was an increasingly ‘small space’ for such a continent to exist.

Ultimately, the accounts of coastal Otago produced by the Endeavour voyage were not especially deep, particularly compared to the rich stores of knowledge accumulated during its visits to the east coast of the North Island, Queen Charlotte Sound and Fiordland. Nevertheless, while coasting Otago, the Endeavour’s officers and crew established the contours of the coastline and plotted some key features of both the land and seascape. But they had no human interaction and Europeans did not enter Otago harbour until 1809-10, during voyage of the sealing vessel, the Brothers. Thus coastal Otago was only slowly incorporated into the commercial reach of New South Wales and the trading networks of the British empire, but once those connections were established they did have profound consequences, consequences we shall explore in later posts.

Tony Ballantyne

Note: in this post,as in all of our posts, we follow the normal convention of historical scholarship in following the original spelling and punctuation found in the primary source.

References:

Atholl Anderson, The Welcome of Strangers: an Ethnohistory of Southern Maori A.D. 1650-1850 (University of otago Press, 1998).

J. C. Beaglehole ed., The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks 1768-1771 (Angus and Robertson Limited, 1962).

J. C. Beaglehole ed., The Journals of Captain James Cook on His Voyages of Discovery: Vol. 1: the Voyage of the Endeavour 1768-1771 (Cambridge University Press, 1968).

Ian Church ed., Gaining a Foothold: Historical Records of Otago’s Eastern Coast, 1770-1839 (Friends of the Hocken Collections, 2008).

The ‘Wisdom Religion’ in Dunedin

With the founding of our local Lodge of the Theosophical Society in 1893, Asian religions and traditions loomed large in the spiritual and intellectual lives of some Dunedinites.

‘Servants of the Star, 17 Dowling St., 1919-1920’. The Dunedin chapter of the Servants of The Star, a Theosophical youth organisation, with Miss Agnes Inglis, an influential Dunedin Theosophist, on the right. Dunedin Theosophical Society Collection.

Asian places, peoples and practices shaped and reshaped colonial society, playing an important part in the making of “New Zealand culture” as we know it today. Dunedin’s Theosophical Society provides a strong example of this trend: the Society brought the “oriental renaissance” to Otago as it members saw opportunities for intellectual stimulation and spiritual revivification in Asian religious traditions. Concepts such as karma, samsara (reincarnation) and nirvana offered new ways of thinking about the nature of life and its meaning. Theosophists were especially attracted to the “ancient wisdom” they believed was stored in important Indian texts like the Vedas and the Bhagavad-Gita. More generally, they were very interested in comparative religion and were deeply committed to the ‘universal brotherhood of humanity without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste, or colour’.

Initially founded in New York city in 1875, the Theosophical Society quickly emerged as a prominent international movement. Local branches or lodges flourished across the globe in the 1880s and the 1890s: the first New Zealand lodge was established in Wellington in 1888. Local lodges organised reading groups, discussion circles and public lectures and provided members with access to library collections and reading rooms. Effectively, the Lodges were sites where books, ideas and arguments were exchanged. Theosophists in New Zealand were part of a global association: they were part of the Australasian Section of the Society and built strong connections to the Theosophical Society’s international networks which had a wide reach from Adyar, in the Indian city of Madras, which became the Society’s headquarters.

Presbyterianism was a powerful influence on the development of early Dunedin, but the city also was home to a significant cohort of freethinkers and individuals interested in new religious movements, such as Theosophy. The first Dunedin name to appear on the international role of the Theosophical Society’s membership was that of Augustus William Maurais, the son of a London bookseller who arrived in Otago in 1875 and became prominent as a journalist, editor and newspaperman. His early years as a Theosophist in Dunedin were lonely ones until a chance meeting with wealthy tannery owner Grant Farquhar, who Maurais noticed on the train from Sawyers Bay to Dunedin reading a Theosophical magazine. In 1893 Maurais and Farquhar were joined as founding members of the Dunedin branch of the Theosophical Society by Robert Pairman, Frank Allan, John Oddie and Thomas Ross: their newly-established Lodge was the third in New Zealand to have a charter issued. From the 1890s, women were actively involved in the Dunedin Lodge and held a range of offices, including the position of President.

‘The Hartley Family c. 1900’, Muir & Moodie. Local pianist and music teacher John K. Hartley and his family are representative of the middle class, intellectual character of Dunedin’s early Theosophists. Dunedin Theosophical Society Collection

Although the Society’s selective approach to new membership meant that it grew slowly – with 18 members in 1896 and 39 in 1900 – its interest in non-western religions caused considerable anxiety. Dunedin’s newspapers showed a persistent interest in both the Society’s international programme and its local growth. The Evening Star ran an “exposé” column written by a London correspondent, the Otago Daily Times closely followed the activities of prominent Theosophist Annie Besant, while The Triad printed a detailed account of Theosophy with the explanation that there was so much public interest in Theosophy that this new movement could be no longer ignored. The Christian Outlook, edited by the influential Presbyterian minister and social reformer Rutherford Waddell, resentfully commented on the ‘excitement; Theosophy had induced in Dunedin.

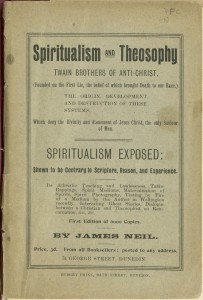

James Neil, a local chemist, produced a pamphlet Spiritualism and Theosophy Twain Brothers of the Anti-Christ that summarised the hostility that some Dunedinites felt towards this new movement: by synthesising the “ancient wisdom” of the Holy Bible with the Vedas, the Bhagavad Gita and the Koran, Neil judged Theosophy guilty of reducing “Jesus to the level of man” and “the Bible to the level of other books”. To Neil and many other Christians in Dunedin, the interest of the city’s Theosophists in the “heathen faiths” of India was a threat to the authority of the Bible, the Protestant churches, and the morality of the colony.

Although the Dunedin Lodge of the Theosophical Society remained small, until World War One it was particularly prominent in Dunedin’s intellectual and cultural life, feeding debates over a range of issues from karma to astrology, vegetarianism to the value of “occult” knowledge. Interest in these areas was in part generated by the visits of prominent Theosophists from overseas – Mrs Cooper Oakley in 1893, Annie Besant in 1894 and 1908, the Countess Wachmeister in 1895 and Colonel Olcott in 1897 – whose public lectures grew significant audiences and stimulated further controversy.

The Dunedin Lodge persisted through these public arguments and continued to support its members in exploring ancient texts and new ways of looking at the world. It also provided an important source of fellowship and sociability for a cluster of Dunedin families as well as visitors.

‘T.S. Convention, Picnic at Broad Bay, 1917’. A picnic at Broad Bay, 1917. Wm. Augustus Maurais, founding member and dedicated champion of Theosophy in Dunedin can be seen centre-left, standing with hands clasped. Dunedin Theosophical Society Collection.

Many Dunedinites will remember the impressive turreted building the Lodge occupied at 236 High Street (after moving from its earlier location in leased rooms in Dowling Street). Having just taken up residence in the old Fitzroy Hotel building on Hillside Road, the Dunedin Theosophical Society Lodge, one of city’s most enduring cultural institutions, is showing no sign of slowing down.

Violeta Gilabert

References:

A.Y. Atkinson, ‘The Dunedin Theosophical Society, 1892-1900’, BA Hons Dissertation, University of Otago, 1978.

Tony Ballantyne, ‘India in New Zealand’, in his Webs of Empire: Locating New Zealand’s Colonial Past, Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 2012, 82-104.

James Neil, Spiritualism and Theosophy Twain Brothers of the Anti-Christ, Dunedin: Budget Print, c.1901. (A copy is held in Hocken Collections).

Further InformatIon: