The second of our series from Practising History (HIST 353) students, this is Shinay Singh’s response to an Otago Preventive Medicine dissertation. An invaluable primary source of New Zealand medical and social history, the Preventive Medicine dissertation collection comprises more than three thousand public health projects written by fifth-year medical students from the 1920s to the late 1970s. Topics range from studies on current health issues, such as asthma, to health surveys of various occupational groups and of New Zealand towns and Maori. Permission is required to access the dissertations. An index to the dissertations is available.

Typhoid fever was and still is a serious illness for anyone to contract. In 1932 two fifth year medical students, L.P. Clark and R.J. McGill, conducted a public health survey of the Bluff township looking at the sanitary standards of industries associated with Bluff, specifically the oyster industry.

In 1929 news articles of six cases of typhoid fever outbreaks in Christchurch were suggested to link back to the consumption of Bluff oysters. The Bluff oyster industry was about to go international with refrigerated live and canned oysters. This potentially serious health risk, therefore, needed to be examined more closely.

Public Response

Strong denial was the response to the accusation that the source of the outbreak lay in the consumption of Bluff oysters. An Invercargill man called it all ‘bunkum’, that it was the housewives who “often keep them a week and expect them to remain good.”[1] The fact that the oysters were “kept in good salt-water”[2] at the wharves in Bluff Harbour was used to suggest they were healthy. Professor Hardman and Professor Boyce had done research into disease and oysters in 1899 and found that oysters could carry bacteria for up to 10 days. The lifespan of the bacteria could apparently be inhibited by pouring salt-water over them or storing them in pure water.[3] The fact that sewage contaminated the Harbour may have increased the likelihood of contamination.

Oyster Harvesting

The oyster season occurred from February 1st to September 30th. The students Clark and McGill were able to go on board the ‘Wetere’ oyster boat to observe the oyster harvesting process. An average of 80 sacks were yielded a day with each sack containing about 70 dozen oysters. The oysters were dredged up from the Foveaux Strait oyster beds and piled onto the deck of the boat. Clark and McGill noted the men standing all over the pile of oysters as a potential contamination point. The oysters were then brought back to Bluff Harbour and stored below the wharves in a pile for transportation to the local cannery or to buyers who wanted fresh oysters.

Oyster boat with fishermen standing on pile of oysters. ODT Collection. Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago, Dunedin, https://hocken.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/11281.

Canning Process

Oysters were brought in from the wharf on carts to the cannery. They were opened by employees, then sent to be washed in a kauri tub. They were then canned in half pound tins that held around 18 oysters per tin. In the tin they were sent through a hot box with steam pipes that both sterilised, and partially cooked the oysters. The tins were stored in an incubation room at 38°C. Clark and McGill noted that this was the most sanitary way of shipping oysters. Any water contamination was prevented by the high heat of the hot box steam pipes.

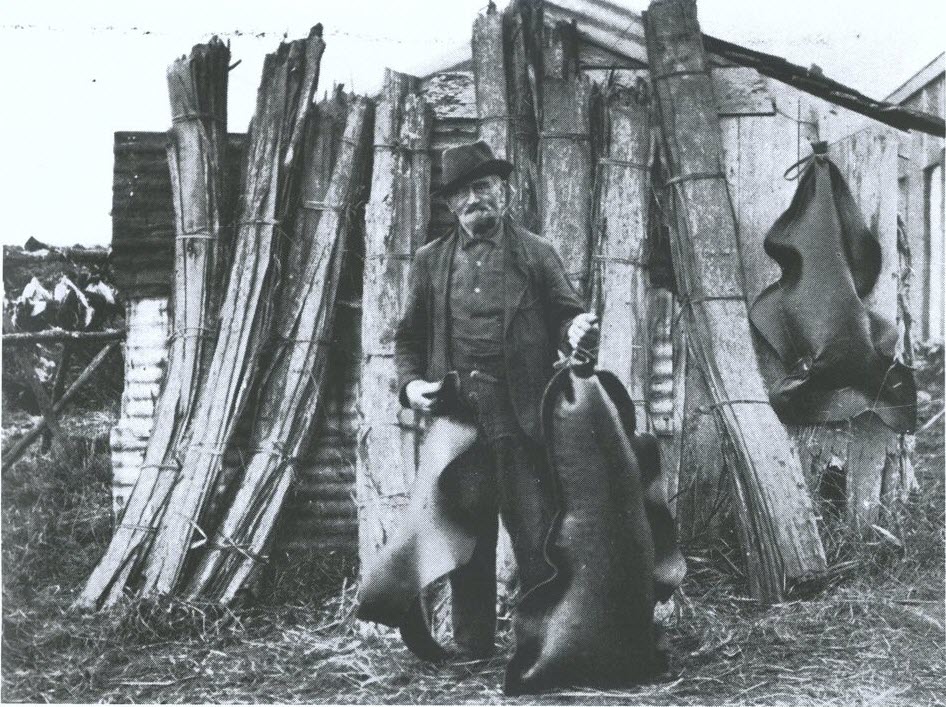

Muttonbirding

Muttonbird harvesting was and still is restricted to Māori who have claims to the industry. The season began on March 18th of every year and everyone must be off the islands by the end of May. Oyster boats took them to the Muttonbird Islands to harvest. In exchange for this, the captains of the oyster boats received a kit of muttonbirds. Each kit could hold about 3 dozen muttonbirds. They packed the birds into kits, inside these kits were kelp bags. The oils of the birds filled the bag, acting as a preservative. Clark and McGill were highly suspicious of contamination, but there was no evidence that anyone had been contaminated by muttonbirds. Thousands of muttonbirds were collected in the season. The kits were sent around New Zealand in cheese wagons to go to shops or individuals for sale.

Materials used in packing kits of mutton birds for marketing: kelp blades blown up to form bags, protecting the kits when full, 1927. Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago, Dunedin, https://hocken.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/16790.

Medical Students Findings

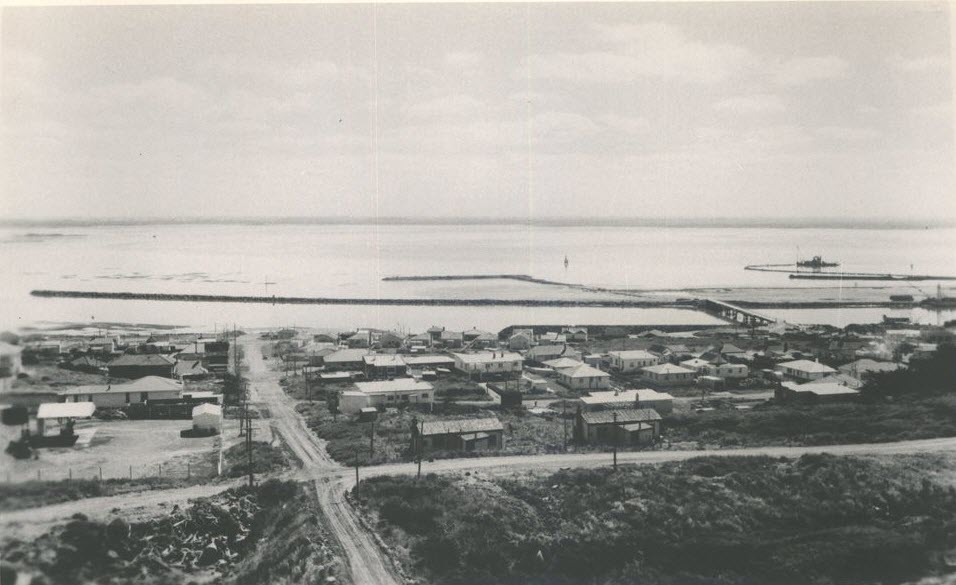

Clark and McGill found that sewage was being disposed of into Bluff Harbour at low tide. The high tide took the sewage by the flood tide to the Foveaux Strait oyster beds. Oysters are filter feeders and so they would consume the small particles of faeces and those who ate the oysters raw were at risk of getting infected with disease as this was how it was spread. The sewage of Bluff residents coming from the flood tide created a volatile combination that could potentially have allowed for the spread of typhoid.

Bluff Harbour. Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago, Dunedin, https://hocken.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/2155.

Medical Students Suggestions

Clark and McGill suggested holding the sewage for 13 days until diseased bacteria died. They also suggested heating the sewage to 65°C to sterilise it. They argued for some sort of sewage treatment before being released into the ocean. Diseases could survive in salt-water for 11-25 days. By treating the sewage this could be reduced to 3-5 days. Bacteria could survive in unsterilised seawater for 3 weeks and could survive in an oyster for 5-6 days.

The students suggested a water carrying system that would go to a pumping station located in the Ocean Beach neighbourhood to remove the town sewage. Then it could be pumped into Foveaux Strait well away from the Harbour. It wouldn’t be until the mid-1960s that Bluff would have a sewage pumping system that would do just as Clark and McGill suggested.[4] And it was much later, in the 1990s, that the sewage being released was treated.[5]

The Oyster Industry Today

There are higher sanitary standards in the Bluff oyster industry today. It is now the oysters themselves that are at risk of disease. Bonamia exitiosa is a waterborne parasite that was found in the Foveaux Strait in 1986. Between 1986 and 1992, 89% of the oyster population was killed.[6] The population was closed off in 1993 to let them repopulate and was opened again in 1996.[7] Since 2016 Bonamia infection levels have been low and oyster populations have been recovering with close monitoring by the Ministry of Fisheries.[8]

[1] “All Bunkum”, Evening Post, 17 October 1929.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Oysters and Disease”, Evening Star, 3 June 1899.

[4] “Sewage treatment and disposal”. Invercargill City Council, accessed 3 August 2019, https://icc.govt.nz/infrastructure/sewage-treatment-and-disposal/.

[5] Ibid.

[6] H.J. Cranfield, A. Dunn, I. J. Doonan, K.P. Michael, “Bonamia exitiosa epizootic in Ostrea chilensis from Foveaux Strait, southern New Zealand between 1986 and 1992”, Journal of Marine Science 62, no.1 (2005): 3.

[7] K. P. Michael, J. Forman, D. Hulston, D. Fu, “The status of infection by bonamia (Bonamia exitiosa) in Foveaux Strait oysters (Ostrea chilensis), changes in the distributions and densities of recruit, pre-recruit, and small oysters in February 2010, and projections of disease mortality,” New Zealand Fisheries Assessment Report 2011/5, (2011): 5.

[8] K.P. Michael, J. Bilewitch, J. Forman, D. Hulston, J. Sutherland, G. Moss, K. Large, “A survey of the Foveaux Strait oyster (Ostrea chilensis) population (OYU 5) in commercial fishery areas and the status of Bonamia (Bonamia exitiosa) in February 2018,” New Zealand Fisheries Assessment Report 2019/02, (2019): 2.

Bibliography

“All Bunkum”. Evening Post. 17 October 1929.

Clark, L.P. and McGill, R.J. “A public health survey of the Bluff with special reference to the Oyster industry” (5th Year Medical Diss. The University of Otago. 1932).

Conn, Ailsa. “The Importance of Norovirus and Cadmium in Shellfish and Implications to Human Health”. (MA. Thes. University of Canterbury, 2010).

Cranfield, H.J. Dunn, A. Doonan, I. J. Michael,K.P. “Bonamia exitiosa epizootic in Ostrea chilensis from Foveaux Strait, southern New Zealand between 1986 and 1992”. Journal of Marine Science 62, no.1 (2005) 3-13.

“Oysters and Disease”. Evening Star. 3 June 1899.

“Sewage treatment and disposal”. Invercargill City Council. Accessed 3 August 2019. https://icc.govt.nz/infrastructure/sewage-treatment-and-disposal/.

Michael, K.P. Bilewitch, J. Forman, J. Hulston, D. Sutherland, J. Moss, G. Large, K.

“A survey of the Foveaux Strait oyster (Ostrea chilensis) population (OYU 5) in commercial fishery areas and the status of Bonamia (Bonamia exitiosa) in February 2018,” New Zealand Fisheries Assessment Report 2019/02, (2019).

Michael, K. P. Forman, J. Hulston, D. Fu, D. “The status of infection by bonamia (Bonamia exitiosa) in Foveaux Strait oysters (Ostrea chilensis), changes in the distributions and densities of recruit, pre-recruit, and small oysters in February 2010, and projections of disease mortality.” New Zealand Fisheries Assessment Report 2011/5. (2011).

Images

Oyster boat, ODT Collection. Hocken Library, University of Otago, Dunedin,

https://hocken.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/11281.

Oyster boats, Bluff, Southland, 1935. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New

Zealand, https://natlib.govt.nz/records/30657435.

Materials used in packing kits of mutton birds for Marketing: Kelp leaves blown up to

form bags, protecting the kits when full, 1927. Hocken Library, University of Otago, Dunedin, https://hocken.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/16790.

Bluff Harbour. Hocken Library, University of Otago, Dunedin, https://hocken.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/2155.