Post cooked up by Emma Scott, Collections Assistant – Publications

My Hocken colleagues are sick of hearing about my love for the air fryer. My air fryer has been moved out of the cupboard and has a permanent home on the kitchen bench. This move is significant as it could have easily been banished to the bottom cupboard with the toastie pie maker and the fondue set. The other appliance in my kitchen on full display is the humble microwave. Like most households, my microwave is used for two things: defrosting and reheating. While it is out of the cupboard due to the two vital functions it performs, I know that I am not realising the microwave’s full potential. It is time to dust off the instruction manual and put my microwave to the test.

This poor little microwave has no idea what’s coming…

According to Te Ara the first microwave ovens appeared in New Zealand in the early 1970s but did not become common until the early 1980s when cookbooks started to include microwave recipes.[1] Growing up in the 90s I remember microwave cookbooks in almost every home I visited. My Mum regularly cooked two recipes in the microwave: custard and chocolate self-saucing pudding (both of which were delicious). The most exciting part about cooking food in the microwave is how little time it takes. For busy families or for people like myself who prefer browsing Netflix to staring at the stove top, the microwave certainly appeals.

Helen Leach states in her book Kitchens: the New Zealand Kitchen in the 20th Century that microwaves weren’t well received overseas. The weight of the early microwaves, the servicing costs and the fears people had about being exposed to radiation were some of the reasons for their lack of popularity. Helen states on page 241 that:

“…few New Zealanders understood the physics behind microwave ovens. They did not understand the difference between the more potent ionising radiation (as in x-rays and gamma rays) and non-ionising radiation (as in radio waves, microwaves, infra-red and invisible light). Some people confused heat –producing microwave radiation with radioactivity.”

It is very understandable that people would be fearful about using the microwave. How would you know the difference between ionising and non-ionising radiation unless you remembered being taught about it, had an interest in science, or worked in a field which required that kind of knowledge? Despite some of the public’s misgivings, by the end of 1983, 1 in 10 New Zealand homes had a microwave oven. ([2], p.242)

The Hocken Library has a significant collection of microwave cookbooks dated from 1979 to 1995, except for one which is dated 2005. I found several recipes I wanted to try from the cookbooks in our collection. I must admit that I am a little apprehensive about how appetising these recipes will be, having turned a crispy golden Jimmy’s pie into a soggy mess using a microwave in the past. I chose a recipe for scrambled eggs just purely out of interest and planned a “gourmet” dinner for myself and my partner using Chef Mike.

Recipe number one from: Alison Holst’s Microwave Book [3]

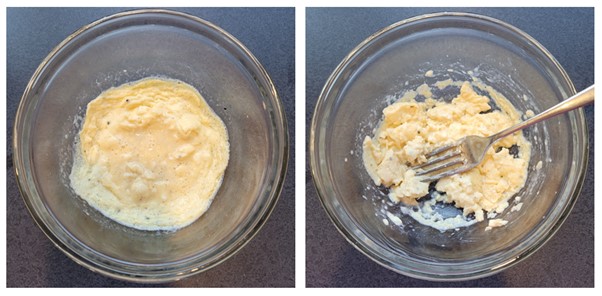

Scrambled Eggs

- Melt a teaspoon of butter in a suitable shallow dish.

- Break an egg into it. Add 1-2 tablespoons milk and beat with a fork until mixed

- Microwave on high for about 20 seconds, until the egg is partly set, then stir with the fork. Add a little chopped parsley or chives if desired.

- Microwave again on high for about 20 seconds long. Stir gently again. Egg will continue cooking as it stands.

- If it is not firm enough after a minute, microwave again for a short time.

- Use medium or defrost and longer times if preferred or if white and yolk have not been completely mixed.

Breakfast is the most important meal of the day and I love scrambled eggs! This recipe pleasantly surprised me. I shouldn’t have doubted Alison. The eggs were too wet after step four, so I had to zap them for a few more minutes. The texture of the eggs was more like an omelette than scrambled eggs, but with a good stir and some seasoning it wasn’t too bad. A solid 3 out of 5 stars.

For our gourmet dinner I decided to create a menu. Making Coq Au Vin appealed to me as several famous chefs have a recipe for Coq Au Vin including Julia Child, Jamie Oliver, Jacques Pepin, and Mary Berry. I’m sure Julia Child would be turning in her grave watching me zap this chicken in the microwave though. I chose the “Sticky Rice with Coconut Cream” for dessert as I just love rice pudding.

Recipe no. 2 (main course) from: Microwaving Main Meals and Desserts: the New Zealand Way by Sheryl Brownlee. [4]

Coq Au Vin

4 rashers of bacon

50g flour

125 ml water

125ml dry red wine

2-3 Tbsp brandy (optional)

2 Tbsp fresh parsley

1 bay leaf

1 large onion cut into rings

1 tsp of garlic powder

1 tsp of chicken stock powder

1 tsp ground black pepper

250g mushrooms sliced

1.5 kg chicken pieces

- Trim and cut bacon into small even pieces, place in 4 litre casserole dish and micro-cook on high power for 3-4 min.

- Stir in flour, water and red wine. Add the rest of the ingredients, stirring to coat the chicken pieces.

- Cover and micro-cook on high power for 15 min. Sir well and cook for a further 15 min. Stand for 10 min, remove bay leaf and serve.

The microwave began making some loud popping sounds while cooking this dish which was a bit concerning. When I added the wine to the bacon, flour, and water things weren’t looking very promising. The dish also looked very murky after the first zap but looked better after the second.

The dish turned out pretty well despite initial appearances. I feel the wine we added to the dish, the Esk Valley Merlot Cabernet Sauvignon, made a big difference. Our overall thoughts were that the flavour was a 4 out of 5 and the consistency was a 2 out of 5. The dish pleasantly surprised us and we gobbled up the whole thing, good job Sheryl.

Now for dessert!

Recipe no.3 (dessert) from: The Gourmet Microwave Cookbook: Creative International Menus from the Microwave by Jan Bilton. [5]

Sticky Rice with Coconut Cream

1 cup glutinous (sticky) rice

1 ½ cups of coconut cream

Pinch salt

5 tablespoons sugar syrup

6 large kiwifruit or other fresh fruit in season

- Prepare the rice up to 2 days in advance. Sugar syrup is prepared by boiling equal parts of sugar and water until the sugar is dissolved,

- Wash rice well under cold running water then soak it overnight. Drain and place in a casserole with ½ cup of boiling water. Stir well.

- Cover and cook on high (100%) power for 5 minutes. Stir well. Add another ½ cup of boiling water, stir, cover, and cook for a further 5 minutes. Stir, cover, and allow to stand for 10 minutes.

- Reserve ½ cup of coconut cream. Add remaining cream to the rice with a pinch of salt. Stir in sugar syrup.

- Peel and slice fruit and place in attractively on a serving place. Using a dessertspoon, place a small mound of rice beside the fruit. Top with reserved coconut cream.

This dish was very straightforward to cook, no weird sounds. This recipe was great, though I am a little biased as I love rice pudding. The kiwifruit on top added a lovely freshness to the dish. A very solid 4 out of 5 stars.

I must admit that I was sceptical about cooking these dishes in the microwave, so I was thrilled with how well they turned out. I will be encouraging everyone to dust off their microwave cookbooks and give the recipes a try.

Toitū Otago Settlers Museum has an exhibition space dedicated to the twentieth century which has an incredible display of historical appliances. The exhibition space really demonstrates how society and technology has changed rapidly over a short period of time. While using a microwave to cook most of your meals may seem like a thing of the past, I suspect it is only a matter of time before my beloved air fryer is thought of in the same way.

References

[1] Burton, David. ‘Cooking – Cooking technology’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/cooking/page-1 (accessed 24 May 2022)

[2] Leach, Helen. Kitchens: the New Zealand Kitchen in the 20th Century. Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2014.

[3] Holst, Alison. Alison Holst’s Microwave Book. Wellington: INL Print, 1982.

[4] Brownlee, Sheryl. Microwaving Main Meals and Desserts: the New Zealand Way. Auckland: David Bateman, 1988.

[5] Bilton, Jan. The Gourmet Microwave Cookbook: Creative International Menus from the Microwave. Auckland: Viking Pacific, 1990.

What else have we cooked up?

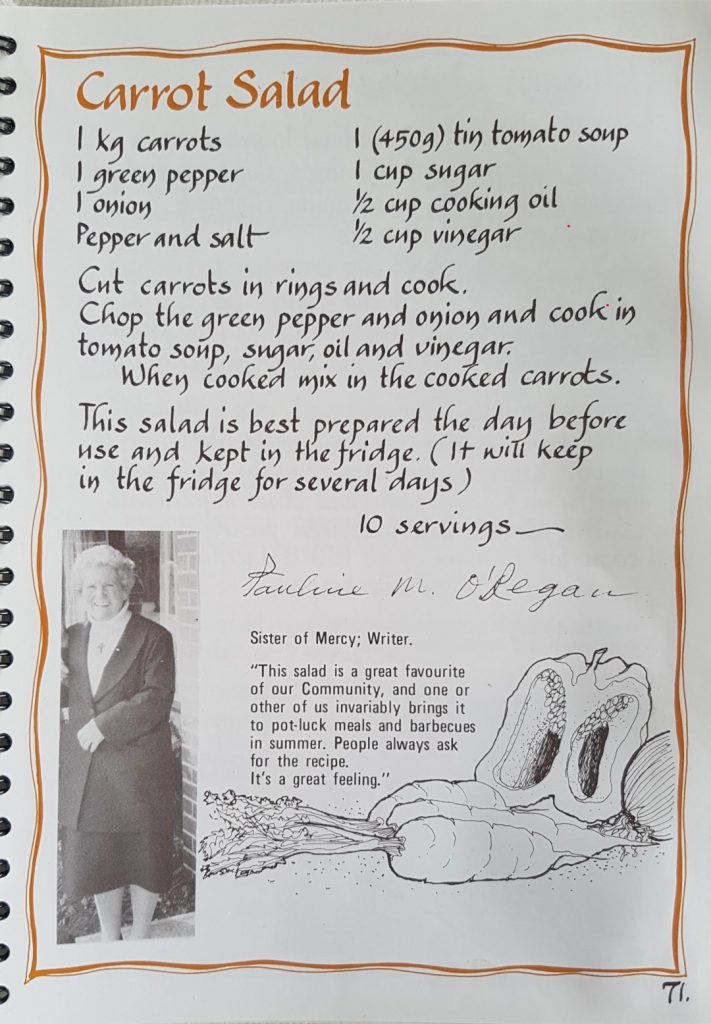

Stirring up the stacks #10: Celebrity Sister O’Regan’s carrot salad

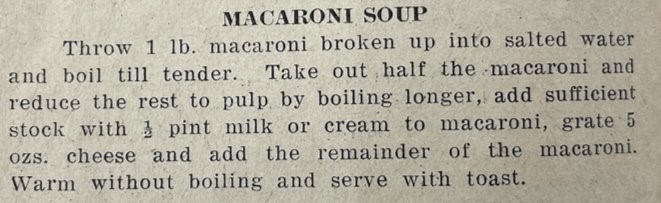

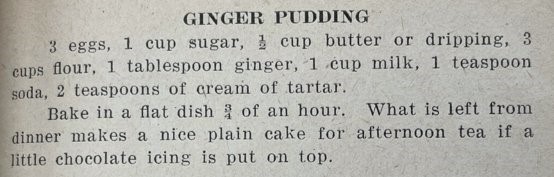

Stirring up the stacks #9: Two for the price of one! Macaroni soup and ginger pudding

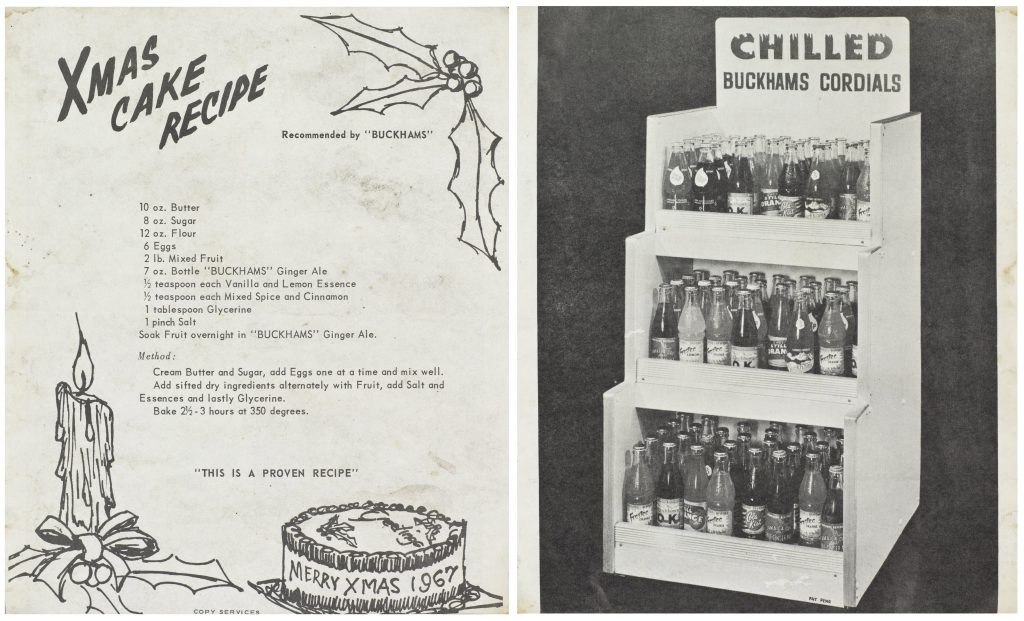

Stirring up the stacks #8: Xmas Cake Recipe Recommended by “Buckhams”

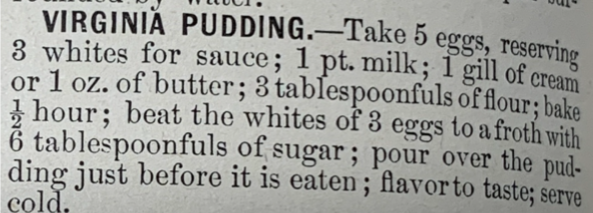

Stirring up the stacks #7: Virginia pudding

Stirring up the stacks #6: Pumpkin pie

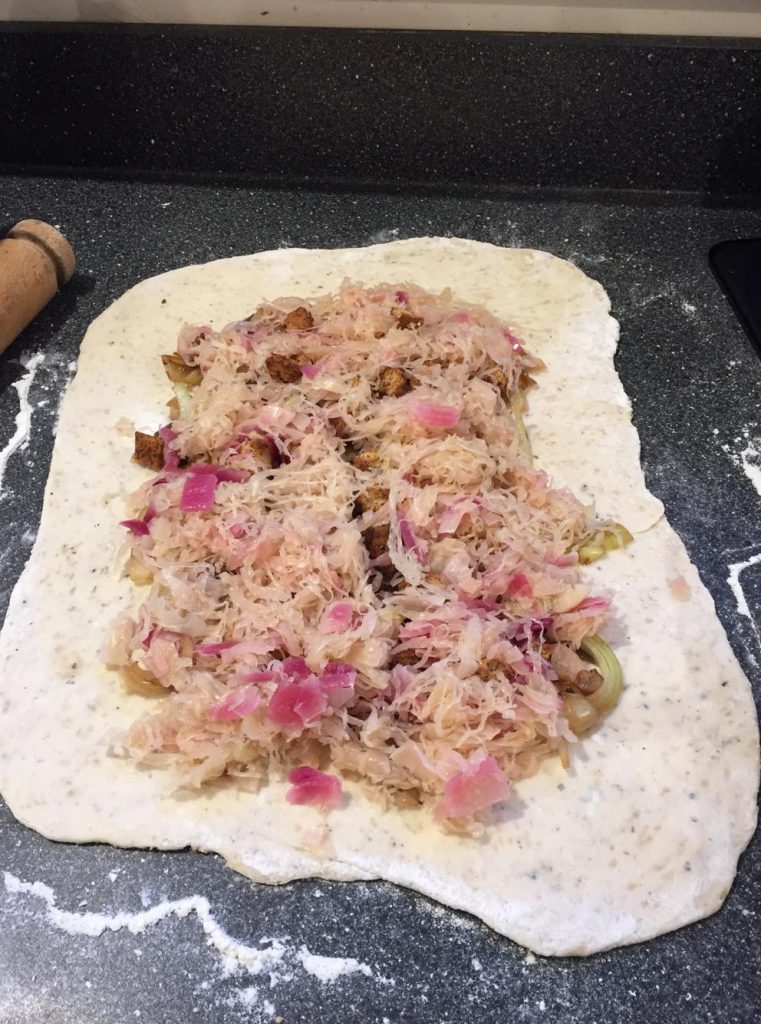

Stirring up the stacks #5: Sauerkraut roll

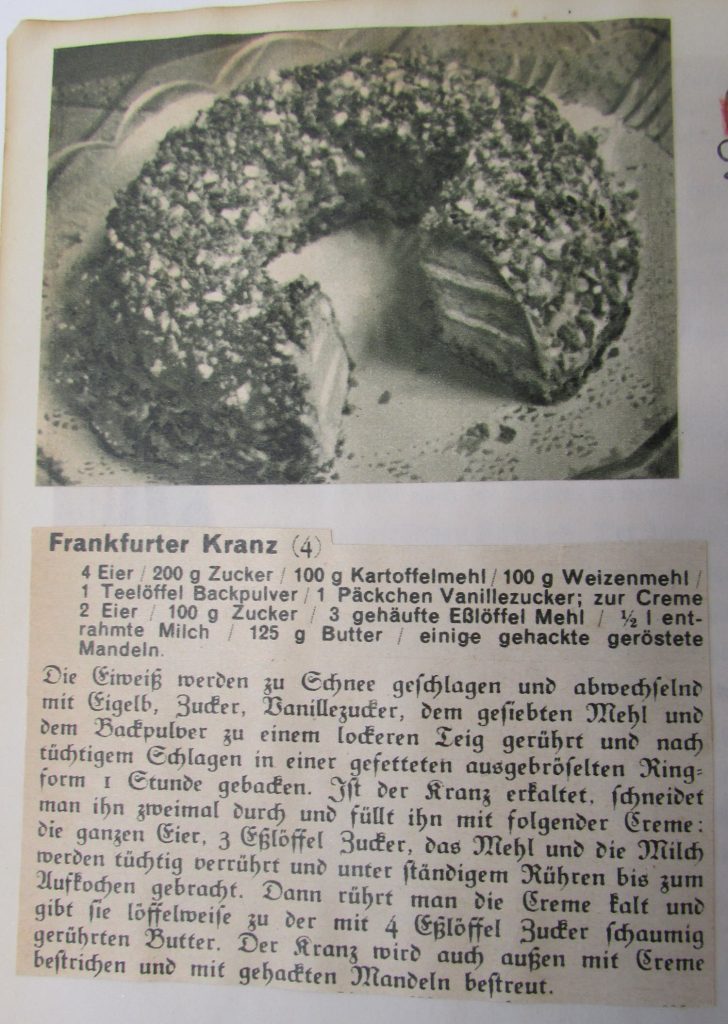

Stirring up the stacks #4: A “delicious cake from better times”

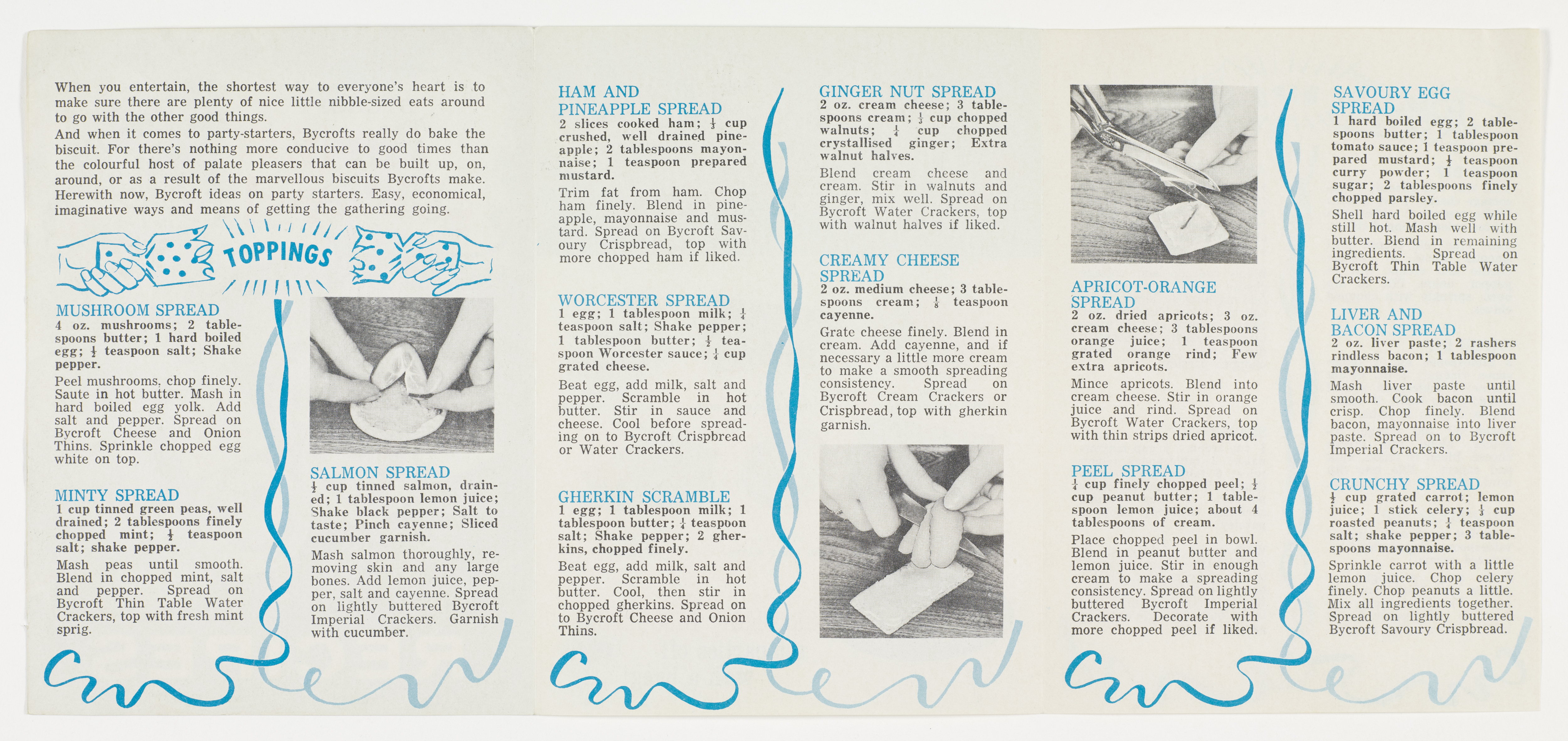

Stirring up the stacks #3: Bycroft party starters

Stirring up the stacks #2: The parfait on the blackboard

Stirring up the stacks #1: Variety salad in tomato aspic