Post researched and written by Andrew Lorey, Collections Assistant (Researcher Services)

Things! They are everywhere! From the beds that we sleep in to the clothes that we wear to the keyboards that we touch, we interact with a greater number and diversity of things on a day-to-day basis than the number and diversity of people with whom we work and live. Though we might not often reflect upon the subtle ways that things impact our daily lives or the powers of things to affect our emotions and moods, we experience the physicality and the material presence of things during every moment of our lives.

Artworks and objects on display in the central ‘Blue Room’ of A Garden of Earthly Delights. Photograph by Iain Frengley.

A Garden of Earthly Delights, an exhibition on view at the Hocken Collections|Te Uare Taoka o Hākena between 11 May 2019 and 11 August 2019, encourages us to think not only about things but with them and through them. Curators at the Hocken Collections collaborated with 13 University of Otago departments and Dunedin cultural institutions to assemble over 180 artworks, photographs, teaching models, books, articles of clothing, rocks, fossils, pieces of furniture and other objects, and the resulting exhibition, in the words of Pictorial Collections Head Curator Robyn Notman, aims “to stimulate ideas and associations that may not always be made between such a diverse group of natural and human-made objects” [1].

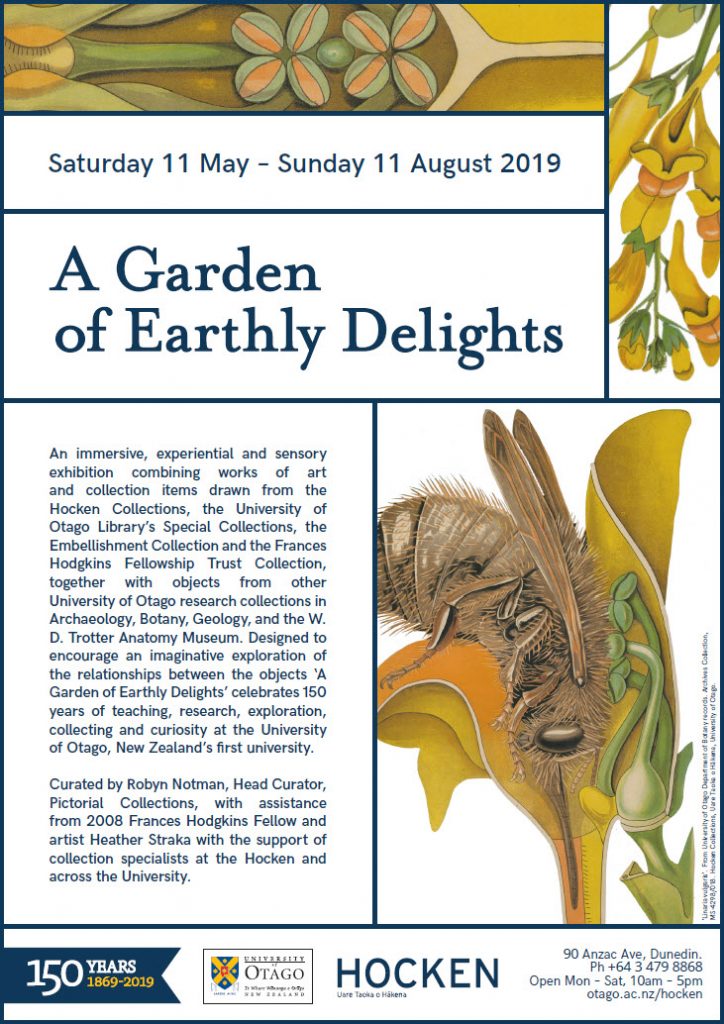

Advertising poster created in conjunction with A Garden of Earthly Delights. Design by Erin Broughton.

Articles, interviews and reviews published by media outlets throughout New Zealand have enabled Notman and other Hocken staff members to explain the motivations and intentions behind the exhibition [2] [3] [4] [5], but few of these published accounts have discussed the particular effects and associations created by interacting with specific objects on display. Indeed, it is difficult to capture in words the profound ways that material objects and artworks can captivate an exhibition’s viewers or spark people’s imaginations. Because no two people have had the same life experiences, forged the same memories or viewed the world in exactly the same way, things have great powers and potentials to elicit emotional responses and to convey various forms of knowledge.

The Neanderthal bust on loan from the University of Otago Archaeology Programme confronts exhibition visitors as they enter the Hocken Collections Gallery. Photograph by Iain Frengley.

Upon entering A Garden of Earthly Delights for the first time, I was confronted by the immediacy and tangibility of the multitude of things that were on display. For instance, a plaster bust of a male Neanderthal (Homo neanderthalensis) greeted me as I entered through the Gallery door. An extinct species of human that coexisted and interbred with anatomically modern people (Homo sapiens), Neanderthals have captured the popular imagination for over a century [6] [7]. Archaeological and genetic discoveries over the last 20 years have dramatically changed our understanding of Neanderthals’ ancestral relationships to modern humans [8] [9], and commercial interests as specialised as perfume manufacturers have sought to capitalise on our cultural fascination with ‘cave-men’ and ‘cave-women’ [10]. Positioned at waist-level height and staring directly at me when I walked in, the Neanderthal felt like a gracious host who was welcoming me into his place of abode.

Used by the University of Otago’s Department of Anthropology as a teaching model, this particular Neanderthal cast has lost much of its contextual information. Its exhibition label identifies its maker as ‘Unknown’ and provides a date of creation as ‘c. 1975’ [11]. Some people might think that this lack of information could discourage exhibition visitors from engaging with the bust, but the scarcity of contextual knowledge about the Neanderthal cast actually helped me to reflect on the actual undertaking of archaeological and anthropological research. By reading the exhibition label and then looking at and thinking about the bust, I was having an experience similar to that of an archaeologist discovering an artefact or bone that has been buried under the surface of the Earth. I did not know who made this plaster cast, where it came from or how old it was, but I knew what it was and how it made me feel. In thinking about this material object, I was able to better understand the difficulties and limitations of academic research in archaeology and anthropology.

Nestled in the corner of the ‘Blue Room’, George R. Chance’s Karearea depicts an endemic New Zealand bird in all its grandeur. Photograph by Iain Frengley.

Moving away from the Neanderthal bust and into a different corner of the Hocken Collections gallery space, I was drawn to a large-format photographic print of a kārearea (New Zealand falcon; Falco novaeseelandiae) [12]. Measuring 200 x 115 cm, the print depicts the kārearea at approximately 5x its actual size. The print’s coexistence with other artworks and objects within the gallery space, including larger-than-life botanical teaching models and nearby paintings by Frances Hodgkins and Robin White, helped me to become aware of the tensions that exist between natural and human-made environments. George Roger Chance, the son of a prominent New Zealand-based photographer, captured this image of a falcon around Flagstaff or Mount Allan (localities north of Dunedin), suggesting that this particular kārearea must also have been keenly aware of its coexistence with humans and their material-cultural creations [13].

The simple black-and-white colouring and the central positioning of the falcon in the photograph also encouraged me to stop and contemplate the things that this kārearea may have been feeling or thinking when its photograph was taken. What would it be like to spend my days gliding through the skies under the strength of my own body? What would I do if I had powers of eyesight that allowed me to spot a rabbit in a paddock at a distance of 16 kilometres (the human equivalent of a falcon’s eyesight)? These are just a couple of the questions that crossed my mind when I stopped to think about the photograph in front of me.

Beyond the biological wonders of the falcon depicted in the print, the seemingly straightforward title of the work – Karearea (New Zealand falcon) – also encouraged me to stop and reflect. Because it refers to the falcon in both te Reo Māori and English, the print reminds anyone who sees it to consider the importance of biculturalism and to appreciate the fact that the same thing – in this case, a bird – can represent very different things to different people. After all, tangata whenua formed ideas about and associations with kārearea throughout Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu long before New Zealanders began to ‘scientifically’ understand, classify and interpret the ecological importance of New Zealand falcons [14]. In this case, a photograph – the thing that was in front of me – caused me to think beyond myself, to imagine and to realise my own personal position within a larger world.

These two embroidered skirts were made by Louise Sutherland, a famous long-distance cyclist who was the first person to cycle the Trans-Amazonian Highway. Photograph by Iain Frengley.

Entering into one of the exhibition’s smaller rooms, I noticed a pair of brightly coloured hand-embroidered skirts hanging together against the backdrop of a pink wall. Even at first glance, it was clear that the skirts were something more than clothing. Delicate butterflies, multi-coloured flowers, animals, rainclouds and sunbeams adorn these skirts, and a lone cyclist traverses both pieces of clothing. The nearby exhibition label explained that Louise Sutherland, a famous New Zealand cyclist and nurse, made the skirts to commemorate a 4,400-km journey that she took through the Amazonian rainforest [15]. After becoming the first person to cycle the Trans-Amazonian Highway, Sutherland spent several years giving lectures in order to raise funds to establish a health clinic in Humaitá, Brazil, usually wearing the eye-catching skirts in order to capture the attention of her audiences.

Having learned a little more about the skirts from reading the exhibition label, I suddenly understood that many layers of meaning and of memory were woven into the fabric of these beautiful things. Of course, the embroidered designs visually told the story of a New Zealand woman who defied all odds by cycling over 4,400 kilometres through a dangerous and wild environment, but the skirts themselves were also physical and material testaments to the efforts Louise made to create them and to educate people about the needs of impoverished communities in the Amazon [16]. Through their stunning visual qualities and their lively histories of use, the skirts gained a particular dynamism and power that helped transport me to Brazil and enabled me to imagine what it must have been like for Sutherland to have undertaken her journey over 40 years ago.

A selection of illustrations and objects on display in the ‘Pink Room’ of A Garden of Earthly Delights, showing the large wooden table on loan from the University of Otago Department of Geology. Photograph by Iain Frengley.

Turning away from the embroidered skirts, I began to observe the other artworks and objects that were on display in the Garden of Earthly Delights. I noticed a variety of botanical illustrations on the walls around me, some anatomical drawings and models and a long table in the centre of the room which supported a large book and about 10 papier-mâché botanical models. As I walked around this section of the gallery, I gradually became aware of the fact that the unassuming table greatly affected my physical impressions of the space. Furniture might just represent the most underappreciated class of material things that we encounter in our lives. After all, we spend most of our time sitting in chairs, sleeping in beds, setting meals on tables and working at desks. We more often think of furniture in terms of its function rather than its form or visual beauty, and as a result, we frequently overlook the ways that furniture items can memorialise and embody particular lived experiences, emotions and feelings.

Measuring 242 x 112 x 78 cm, the rectangular table is one of the largest things on display in the exhibition, and it is much more than a piece of carved wood on which to place artworks and objects. It seemed slightly unremarkable at first, due to its lack of decoration and its plainness in comparison to the vibrant illustrations and intriguing objects that surrounded it, and it was also one of the few objects in the exhibition that was not accompanied by a descriptive label [17]. Looking more closely, I realised that the table was not actually plain or undecorated – hundreds of signatures, messages and other types of graffiti adorned its surfaces. It then occurred to me that in the context of this exhibition, this graffiti was not merely a material manifestation of vandalism or some rebellious compulsion. Rather, it seemed to represent a type of crowd-sourced decoration and artistry that had required years of labour, perhaps undertaken in stolen moments when no authorities could intervene. Memories, feelings, frustrations and follies had been inscribed into this table over its decades of use, and therefore the table represented not only a piece of furniture designed to fulfil a particular function but also a material expression of many different aspects of human experience.

Some of the objects, illustrations and artworks on display in the ‘Green Room’ of A Garden of Earthly Delights. Photograph by Iain Frengley.

Each of the things described in this blog post – the Neanderthal bust, the kārearea photograph, the embroidered skirts and the large table – tell different stories about the people who made them, the places they travelled and the ideas that they express. By displaying them in association with the other 180 artworks and objects in A Garden of Earthly Delights, exhibition visitors are given innumerable opportunities to consider things in new ways, often thinking alongside, with and through the things on display. In this way, the exhibition encourages gallery visitors to think creatively and playfully about the world around them. For me, the exhibition served as a powerful reminder that our material surroundings affect us during every moment of our lives, whether we consciously observe them or not. This realisation has stuck with me long after my visit to A Garden of Earthly Delights, and it offered me both a new way of thinking and a new way of thinging.

The entrance to A Garden of Earthly Delights, located on the First Floor of the Hocken Collections. Design by Erin Broughton.

A Garden of Earthly Delights is open for viewing in the Hocken Collections’ First Floor Gallery at 90 Anzac Avenue until 11 August 2019 Monday through Saturday from 10am to 4pm and Sunday, 11 August 2019, from 2pm to 4pm.

[1] Otago Bulletin Board (2019). Uni News – Art and science come together in exhibition. https://www.otago.ac.nz/otagobulletin/news/otago710920.html.

[2] Davies, Caroline (2019). Inside the Hocken: A Garden of Earthly Delights. Down in Edin Magazine. 17(July 2019), 60-75.

[3] Notman, Robyn (2019). Sculpture in kauri gift from McCahons. Otago Daily Times: The Weekend Mix. 08 June 2019, page 6.

[4] Otago Daily Times Online (2019). Exhibition more of a ‘garden’ adventure. https://www.odt.co.nz/entertainment/arts/exhibition-more-garden-adventure.

[5] Exploring Colour (2019). A Garden of Earthly Delights. https://exploringcolour.wordpress.com/2019/05/30/a-garden-of-earthly-delights/.

[6] Sommer, Marianne (2006). Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: Neanderthal as Image and ‘Distortion’ in Early 20th-Century French Science and Press. Social Studies of Science. 36(2), 207-240. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306312706054527.

[7] Pääbo, Svante (2014). Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes. London: Hachette UK.

[8] Slon et al. (2018). The genome of the offspring of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. Nature. 561, 113-116.

[9] D’Errico et al. (1998). Neanderthal Acculturation in Western Europe? A Critical Review of the Evidence and Interpretation. Current Anthropology. Supplement to Vol. 39, S1-S44.

[10] Aude Ltd, a British fragrance company, recently released a unisex fragrance called ‘Neandertal’. The company’s website (https://neandertal.co.uk/) states that the ‘perfume imagines the life of this mysterious being [the Neanderthal] while raising questions of the past and future of modern humans’. I wonder what the perfume smells like…

[11] The full exhibition label for the Neanderthal bust reads:

Maker Unknown

[Neanderthal bust], c. 1975

Plaster

Early hominid/human cast collection, Archaeology Programme

Department of Anthropology, University of Otago School of Social Sciences

[12] You can learn more about the kārearea/New Zealand falcon at the New Zealand Department of Conservation|Te Papa Atawhai’s website: https://www.doc.govt.nz/nature/native-animals/birds/birds-a-z/nz-falcon-karearea/.

[13] The full exhibition label for the kārearea photograph reads:

George R. Chance, 1916-2008, Aotearoa

Karearea (New Zealand falcon), c. 1970

Gelatin silver print

Given by the photographer in 1991

Hocken Photographs Collection P2018-013-009

George Chance (junior) made a study of these falcons in the 1970s and later participated in the making of a documentary entitled ‘Karearea: the Pine Falcon’, which was directed by Sandy Crichton and released in 2008. This particular bird was a local that used to fly between Flagstaff and Mount Allen. George Chance made a number of very large prints like this one using his own enlarger, a Durst 600. A second copy of this photograph was hung in the Hall of Birds at the Otago Museum when John Darby was a curator there.

The photograph hung on the first floor of Cargill House until 1991, and was then deposited at the Department of Zoology at the University of Otago and now resides at the Hocken.

[14] Te Ara | The Encylopedia of New Zealand provides two traditional Māori sayings that refer to the kārearea. The first suggests that the behaviour of the kārearea could indicate upcoming changes in the weather, while the second demonstrates that the falcon was traditionally viewed as bold, treacherous and possibly even as an enemy:

Ka tangi te kārewarewa ki waenga o te rangi pai, ka ua āpōpō.

Ka tangi ki waenga o te rangi ua, ka paki āpōpō.

When a kārearea screams in fine weather, next day there’ll be rain.

When it screams in the rain, next day will be fine.

https://teara.govt.nz/en/nga-manu-birds/page-4

and

Homai te kāeaea kia toro-māhangatia

Ko te kāhu te whakaora – waiho kia rere ana!

The kārearea must be snared

And the kāhu saved – let it fly on!

https://teara.govt.nz/en/nga-manu-birds/page-5

[15] Sutherland, Louise (1982). The Impossible Ride: The Story of the First Bicycle Ride across the Amazon Jungle. London: Southern Cross Press.

[16] Wall, Bronwen (2010). Louise Sutherland: Spinning the Globe. Wellington: Kennett Brothers.

[17] The table is briefly described as follows in a notation on an exhibition label primarily devoted to botanical models:

A note on the table. Presumably this large work table was left in the Department of Geology when the Medical School moved out in the mid-1920s, thus it technically became ‘the Geology work table’ around this time, but came into existence [sic] many years before. Sporting nearly a century of graffiti carved by myriad generations of geology students, it represents the vast and colourful histories of the many departments in this exhibition that host research collections.