Post researched and written by Gini Jory, Hocken General Assistant

When I came across this recipe late last year in the Cyclopedia of valuable receipts: a treasure-house of useful knowledge for the every-day wants of life, by Henry B. Scammell (what a mouthful!) that one of my colleagues had on his desk, I knew I had to give it a go. For some background, my full name is Virginia, and I’ve always had a bit of a problem with it. As a child people always said it in an American accent which I hated, and I never knew anyone else with the same name who wasn’t about 30 years older than me, so it always felt a bit weird. Finding a pudding with my name out of the blue brought up lots of nostalgic memories of searching for notebooks, mugs, key rings and piggy banks desperately looking for one with my name on it. Of course, I was never successful, whereas my sister Emily found her name every. single. time. Secretly, I was quite bitter about this fact.

But now it is finally my time! I have a whole pudding, and that’s much better than a key ring.

Or, at least, I hope it is.

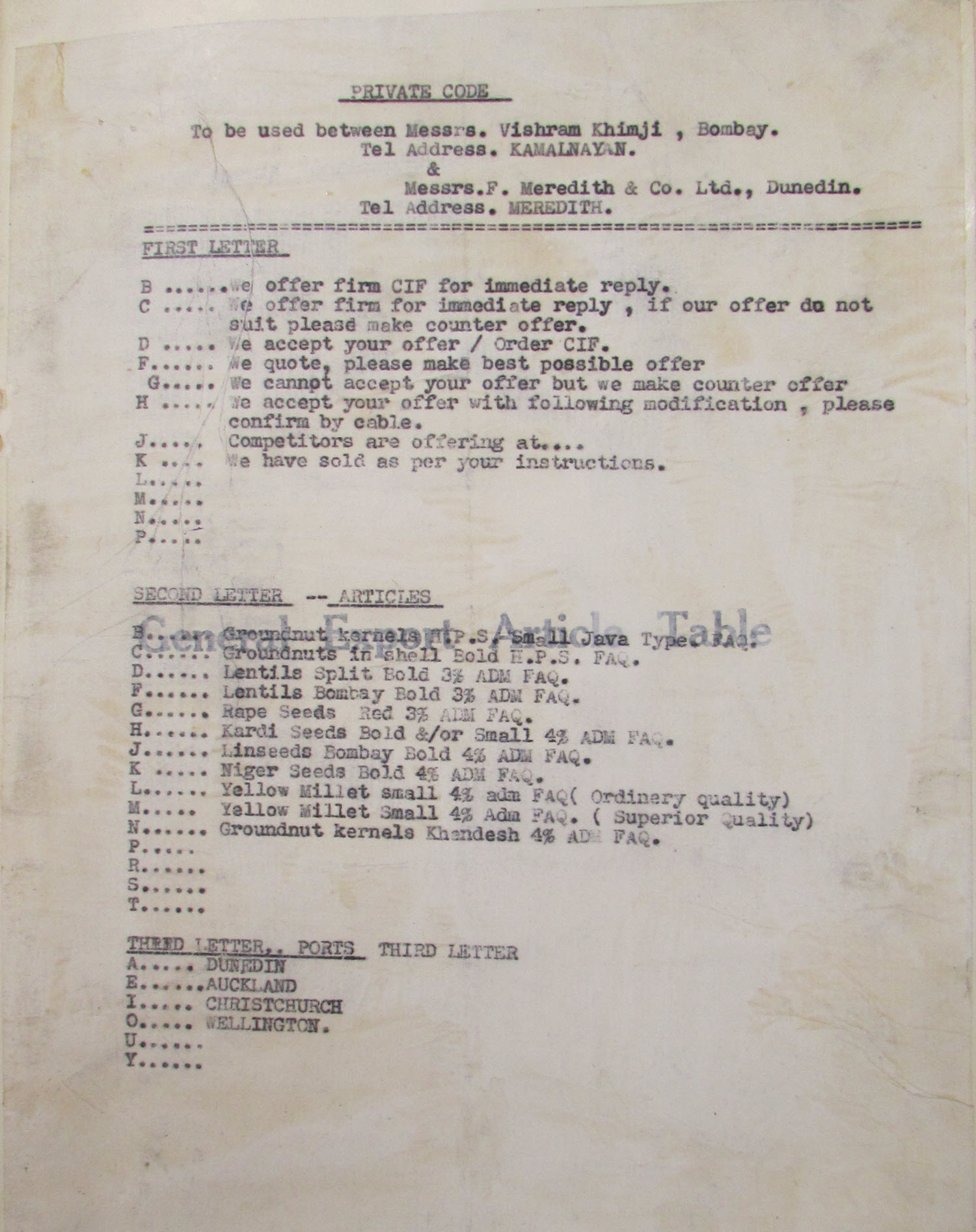

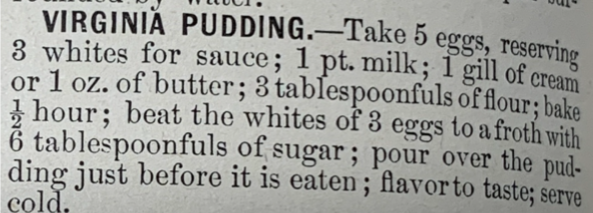

At first look, this recipe has a few issues. Firstly, the whole thing is one tiny paragraph, nothing like recipes in cookbooks these days. And the whole thing is pretty vague on a lot of key points. No temperatures are given; the texture or consistency of the desired outcome is never mentioned, and I don’t know about you, but that frothy raw egg white sauce doesn’t sound great. It also sounds pretty flavourless.

Here is the recipe, split into ingredients and method and with some more modern metric measurements:

Virginia Pudding

Ingredients:

5 eggs (reserve 3 whites for sauce)

1 pt (472 ml) milk

1 gill (142 ml) cream; or 1 oz (28g) butter

3 Tb flour

6 Tb sugar

Method:

Mix all ingredients bar three whites and sugar. Bake for ½ an hour.

Beat egg whites to a froth with sugar. Pour over the pudding just before it is eaten.

Flavour to taste; serve cold.

I originally turned to google to see if I could find anything similar, to get a better idea of what I should be making here. It was rather unhelpful however- plenty of results for Virginia apple pudding, Virginia bread pudding, and even a Virginia chicken pudding. Eventually though, I found a transcription of Housekeeping in Old Virginia, by Marion Cabell Tyree from Project Gutenberg which has a slight variation of the same recipe:

“Virginia Pudding.

Scald one quart of milk. Pour it on three tablespoonfuls of sifted flour. Add the yolks of five eggs, the whites of two, and the grated rind of one lemon. Bake twenty minutes.

Sauce.—The whites of three eggs, beaten to a stiff froth, a full cup of sugar, then a wine-glass of wine and the juice of a lemon. Pour over the pudding just as you send it to the table.—Miss E. S.”

As you can see, the sauce on this one is a bit fancier (and sweeter), and there is some lemon for flavour in the pudding. But there’s still no temperature and no hint as to what this pudding should turn out like.

This was the way practically all recipe books were written at the time, as there were no oven thermometers, no exact way of measuring ingredient weights, and a lot of the methodology was assumed, as the books were mostly used by cooks who knew what they were doing, and didn’t want to waste time writing down recipes. A fun history fact, but not a lot of help to try and translate this recipe into 21st century-speak!

With not a lot to go on, I decided to just get in and give it a go. I had looked up similar looking puddings, like the Chess pie and transparent pudding, which have similar ingredients and origins, so I thought I was probably looking for something that resembled a pumpkin pie, sans crust.

I decided to add a splash of vanilla for a bit of flavour, and I opted to use the cream over the butter.

Having mixed all the pudding ingredients together, it was decidedly wet! Into the oven it went for half an hour, at 180 degrees Celsius, which is what most things I bake seem to be cooked at.

First attempt mixture before baking

First attempt mixture during baking

I had decided I wasn’t super keen to eat this cold, so decided to crack on with the sauce while the pudding cooked. This was… a mistake.

When I took the pudding out, it was still very soft. It had a skin on top but was extremely wobbly. Not thinking this was what I was aiming for, I put it back in for about another 20-30 minutes. I should have held off on the sauce, as the egg whites went very stiff during this time. Because I wasn’t sure about the raw side of it, I put the egg white/meringue mix on top of the pudding and put it back in the oven to make it like a meringue topped pie. If it hadn’t gotten so stiff I could have made it look much nicer, but it was very hard to spread.

First attempt mix after baking

First attempt with addition of meringue baked

First impressions: Egg with meringue on top.

It had a definite quiche like texture, and was still very bland despite the vanilla. the only flavour came from the “sauce” which was nice and sweet. In all honestly, I was disappointed this was the dessert I shared a name with.

First attempt end result

I had been meaning to give it another go to share with my workmates, but due to the Covid-19 lockdown I am currently unable to. However, this did give me another idea- so, I emailed round the recipe and asked everyone what they thought it would taste like, and if it was something they would want to try.

Here are some responses:

“Yes I would definitely like to try this. Maybe with some poached fruit?”

“What is a gill of cream?” (I had never heard of this measurement before either!)

“Anything sweet and comforting looks good to me.”

“I’m intrigued, there isn’t as much sugar as I would have expected for the meringue and there isn’t any vanilla. Perhaps it will taste like a pavlova except not as sweet? Looks yum.”

“I think it would be super bland, no flavour at all! Definitely would try it though as there’s nothing gross going on but would be nice with some berries on the side or something.”

“The pudding looks amazing and sounds perfect for a cool Autumn evening! But the recipe makes it seem like it might be a bit bland as there is nothing to give it much flavour e.g. vanilla or lemon.”

“Reading the recipe the bottom bit is an unsweetened batter pudding, like a Dutch Baby or a Yorkshire pudding, and then it is topped with meringue. Personally I think it might be a bit bland to my 21st century palate and I’d be craving some fruit with it. But back in the day it would have been sweet, filling and easy to digest. And also made from the kinds of ingredients readily available to the home cook. Lockdown food?”

“I’m always a sucker for meringue !!! (and a lot of eggs !)”

One of my colleagues suggested it sounded a bit like a Queen pudding, minus the breadcrumbs and jam. I had a quick google of this, and now that I saw something similar and a properly explained method, I decided to give it another go with my bubble buddies over Easter weekend. This time I did things a bit differently:

I beat the egg mixture, and took the instruction to “flavour to taste” very liberally, adding about 1/3 a cup of sugar and a teaspoon of vanilla to this as well.

I heated the milk and butter (had no cream this time round) on the stove, not letting it boil. Sifted in the flour, mixed and then slowly poured it into the egg mixture in small batches while beating to combine. This resulted in a much puffier mixture than my previous attempt, and I had more mixture, so had to put the extra in a mini ramekin. Popped it into the oven at 160 degrees, slightly lower this time. After 30 minutes I took it out and left to cool on the bench.

Attempt 2 uncooked mixture

Attempt 2 cooked mixture

When we were ready for dessert, I whipped up the egg whites with the sugar, and piped it on top of the pudding. Popped it in the oven on grill for about 5-10 minutes, until the meringue was slightly browned on top. We had it with some boysenberry ice cream, and it was much nicer this time round! More of a baked custard consistency, which I think is probably more what this pudding should be like. I think it would definitely be nice with some poached fruit or a berry compote. I definitely wouldn’t call this my new favourite pudding, but I’m glad I gave it another go and got a better result.

Attempt 2 meringue piped

Attempt 2 final result

Now this is more of a fun weird thing to share my name with, and I’m ok with that.

References:

Scammel, Henry B, c. 1897. Cyclopedia of valuable receipts : a treasure-house of useful knowledge for the every-day wants of life. St. Auckland, N.Z. : Wm. Gribble.

Viet, Helen Zoe, 2017, Smithsonian Magazine. The Making of the Modern American Recipe. Visited 8/4/2020. < https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/making-modern-american-recipe-180964940/>

Mcdaniel, Melissa, originally by Tyree, Marion Cabell. Housekeeping in Old Virginia. Visited 8/4/2020. < https://www.gutenberg.org/files/42450/42450-h/42450-h.htm#Page_365>

What else have we cooked up?

Stirring up the stacks #6: Pumpkin pie

Stirring up the stacks #5: Sauerkraut roll

Stirring up the stacks #4: A “delicious cake from better times”

Stirring up the stacks #3: Bycroft party starters