Post prepared by Jacinta Beckwith, Kaitiaki Mātauranga Māori

Each of us is an epitome of the past, a compendium of evidence from which the labours of the comparative anatomist have reconstructed the wonderful story of human evolution. We are ourselves the past in the present.

H.D. Skinner, The Past and the Present

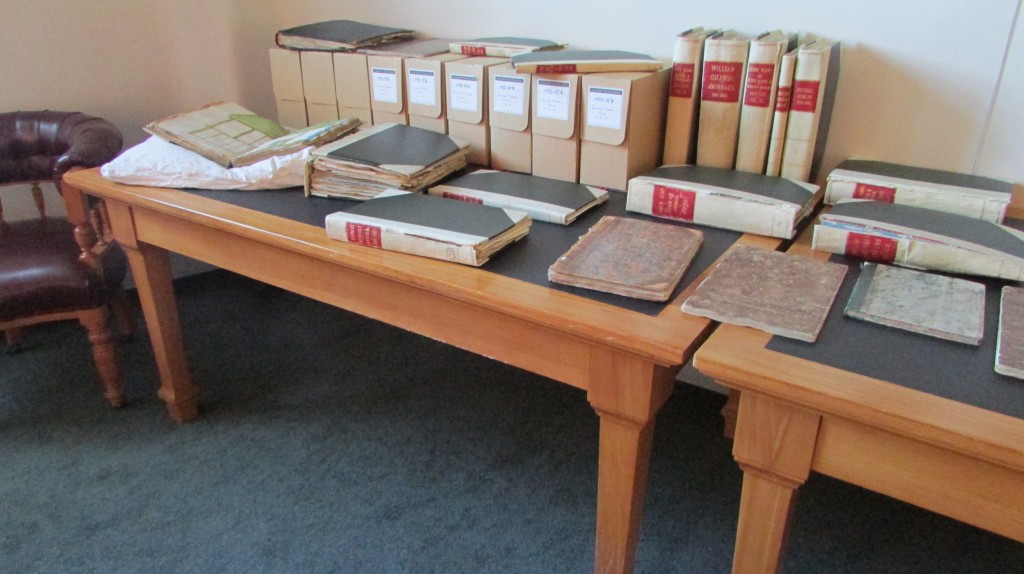

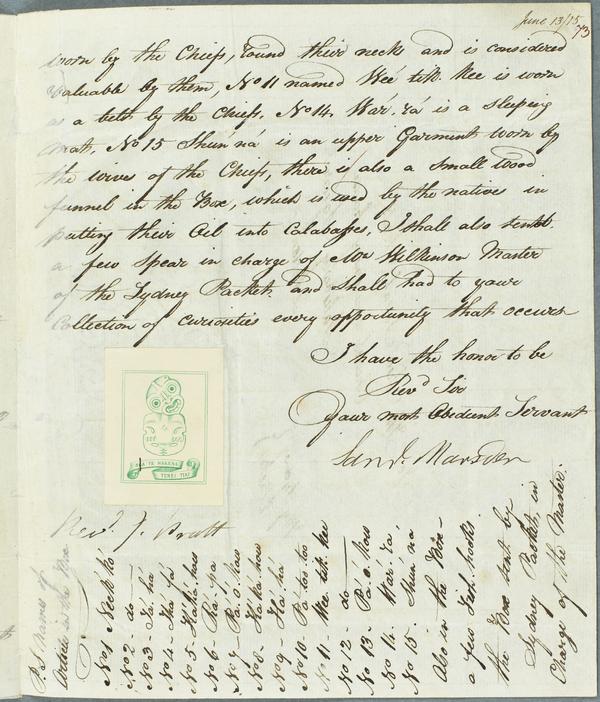

This year’s inaugural New Zealand Archaeology Week (1-7 April) offers an opportune moment to highlight some of the Hocken’s archaeology-related taonga. Examples include the Otago Anthropological Society Records (1960-1983), Anthropology Departmental Seminar flyers (most dating to 1997), and a wide variety of archaeological reports, notebooks, diaries, letters and photographs including papers of David Teviotdale, Peter Gathercole and Atholl Anderson. More recently, our collections have been enhanced by the ongoing contribution of local archaeologists such as Drs Jill Hamel and Peter Petchey who regularly submit their archaeological reports, for which we remain deeply grateful.

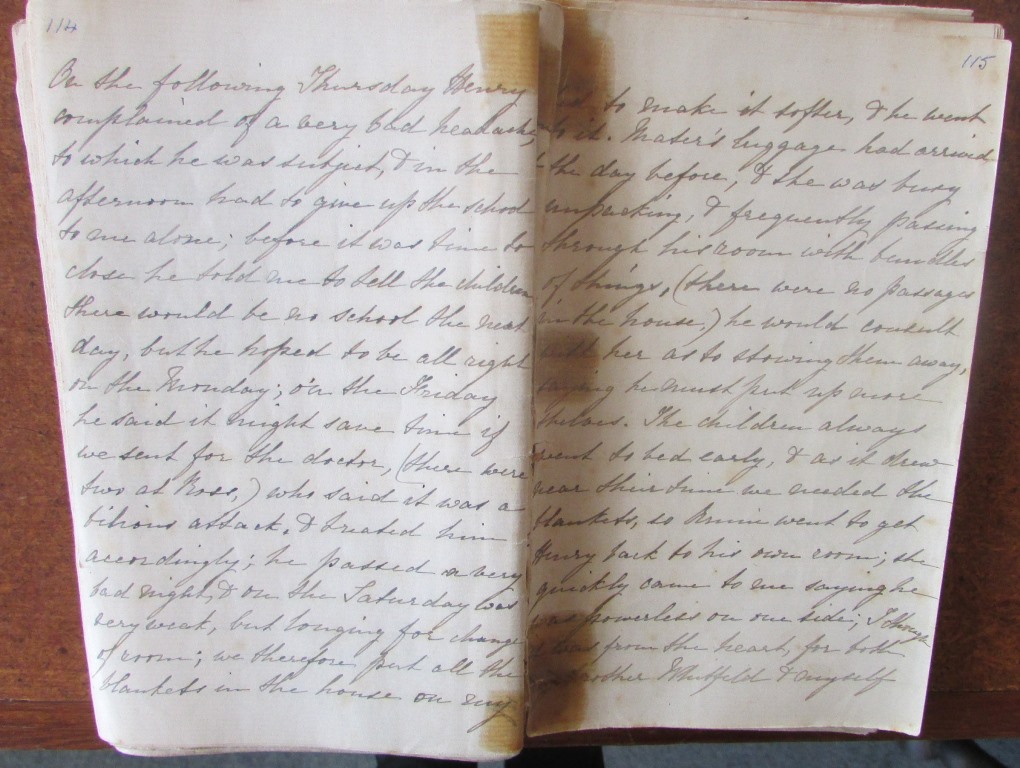

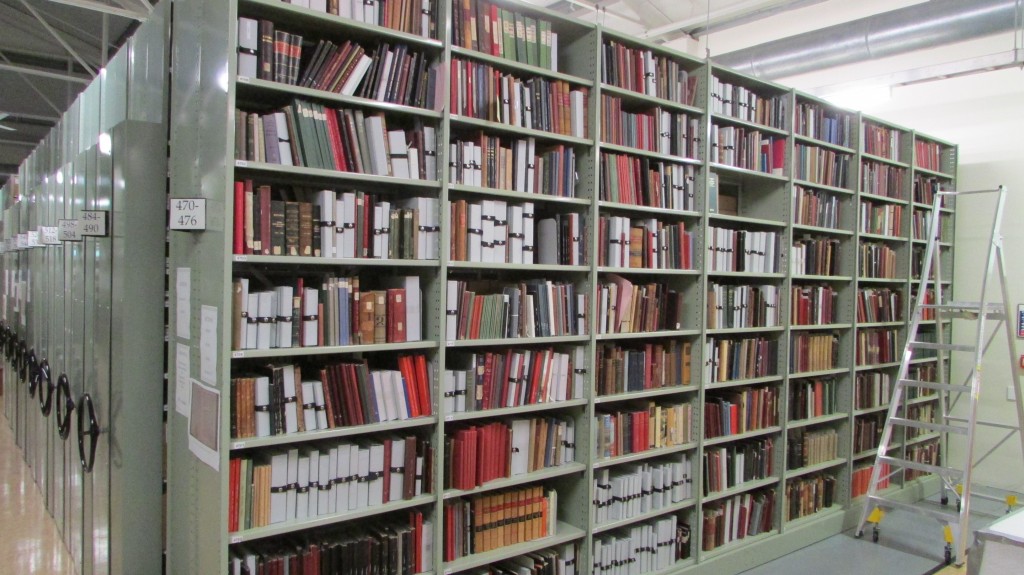

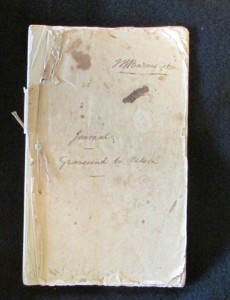

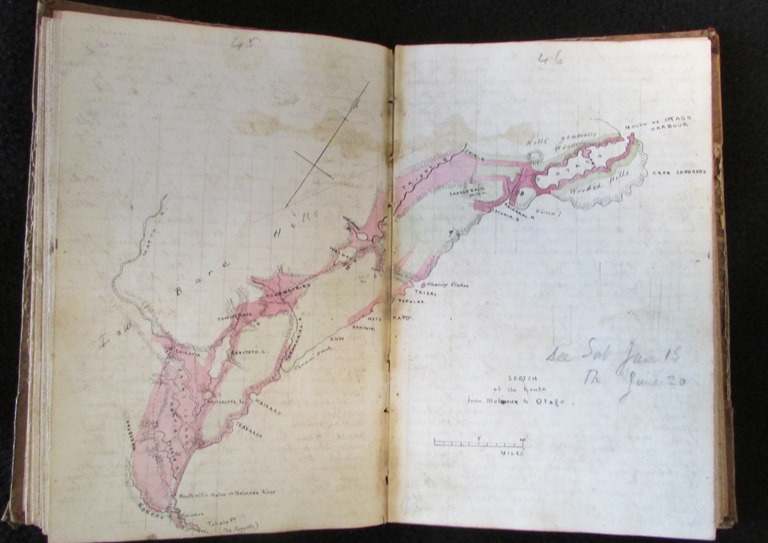

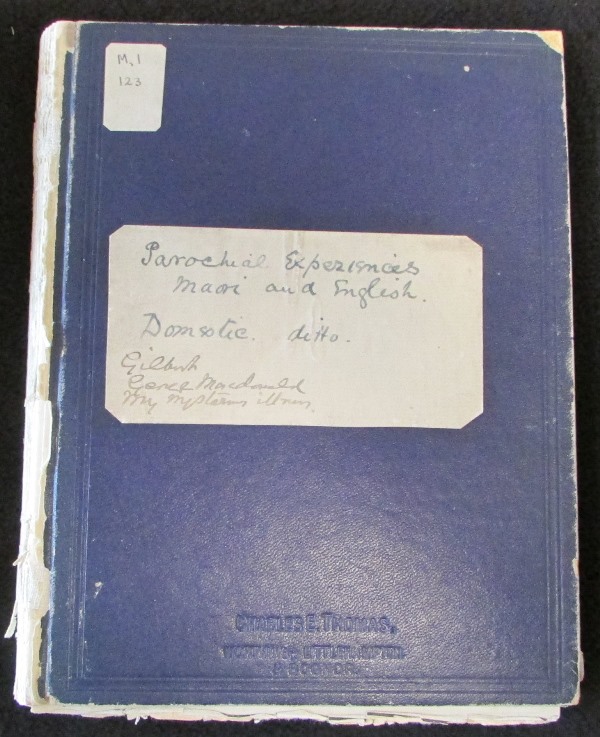

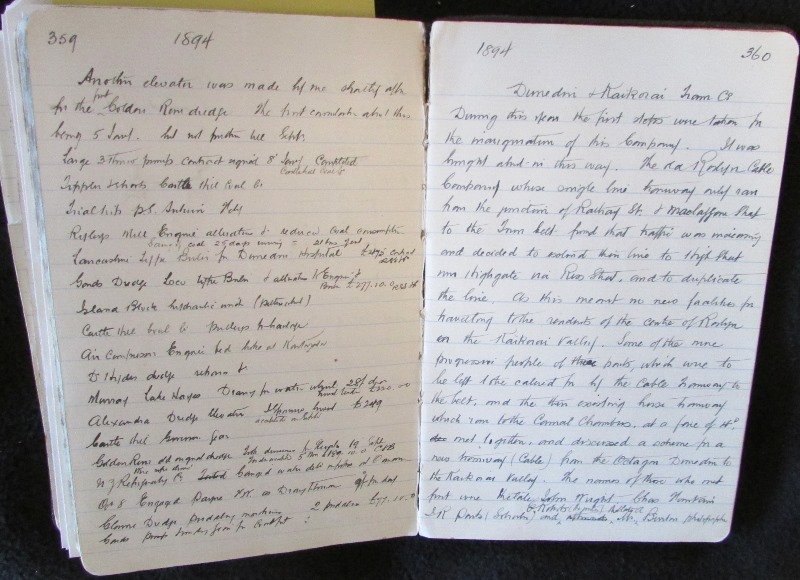

One of our largest collections relating to the world of archaeology and anthropology are the Papers of Henry Devenish Skinner (1886-1978). At 3.14 linear metres in size, this collection comprises folders full of handwritten research and lecture notes, letters, photographs, scrapbooks and newspaper clippings pertaining primarily to Skinner’s archaeological, anthropological and ethnological work with the Otago Museum and the University of Otago, and also to his school days and military service. It includes personal correspondence detailing the collection of Māori artefacts, letters with Elsdon Best, S. Percy Smith, Willi Fels, and other notable anthropologists and collectors. Skinner’s papers also include a significant series of subject files relating to not only Māori and Pacific archaeology but also to that of Africa, Europe, the Mediterranean and the Middle East.

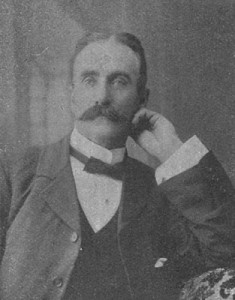

H.D. Skinner is fondly remembered as the founding father of New Zealand Anthropology. He is particularly known for his development of the Otago Museum, for his pioneering work on the archaeology of the Māori and for his comparative studies of Polynesian archaeology and material culture. He was the first Lecturer of Anthropology in Australasia, appointed Lecturer in Ethnology at the University of Otago in 1919 (where he lectured until 1952). He was appointed assistant curator of the Otago Museum in 1919, later becoming Director of the Museum from 1937 until 1957. Skinner was also Librarian of the Hocken from 1919 until 1928. Much of the collection expansion in the Otago Museum, and the importance placed on the collection and display of Māori and Polynesian artefacts can be attributed to him. He also expanded the Hocken’s collections, most notably in New Zealand paintings and drawings.

Skinner’s research on the Moriori represents a milestone in the history of Polynesian ethnology as the first systematic account of material culture of a Polynesian people. He set new standards in description, classification and analysis, and he demonstrated how ethnological research could contribute to important historical conclusions. Professor Atholl Anderson, Honorary Fellow of Otago’s Department of Anthropology & Archaeology, describes Skinner’s analyses of Māori material culture as prescribing the method and objectives of the discipline for over 50 years and his teaching as inspirational for several generations of archaeologists, especially in southern New Zealand.

References:

Anderson, A. Henry Devenish Skinner, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography Volume 4, 1998

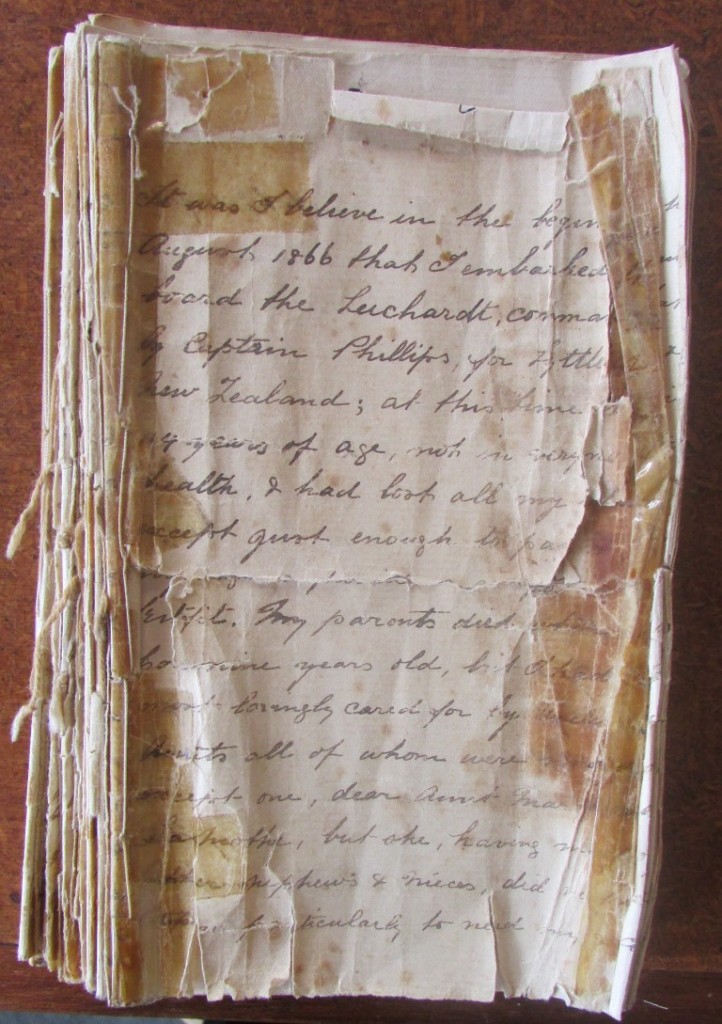

Skinner, H.D. The Past and the Present – Popular Lecture, in Skinner, Henry Devenish Papers, Hocken Archives Collection, MS 1219/071

Wells, M. Cultural appreciation or inventing identity? H.D. Skinner & the Otago Museum. BA (Hons) thesis, Otago, 2014

ITEMS ON DISPLAY

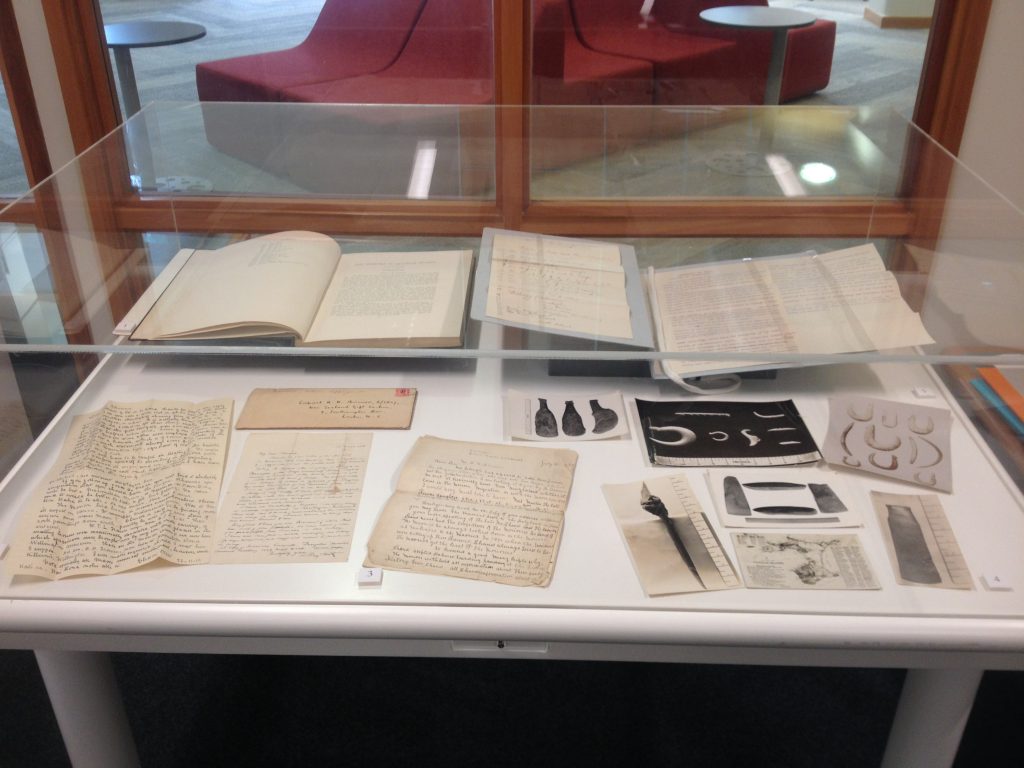

HOCKEN FOYER

Anthropology Department Seminar flyers from the late nineties. Hocken Ephemera Collection

DISPLAY TABLE

- Skinner, H. D. 1923. The Morioris of Chatham Islands. Honolulu, Hawaii: Bernice P. Bishop Museum. Hocken Published Collection

- Letters from Elsdon Best and S. Percy Smith to H.D. Skinner, and envelope addressed to Corporal H.D. Skinner containing further letters and clippings relating to Moriori in ‘Letters, extracts, notes, etc. relating to Morioris’, Skinner, Henry Devenish Papers, Hocken Archives Collection, MS-1219/169

- Letter from J Renwick (1925) to H.D. Skinner in ‘Technology and Art of the [Moriori of the Chathams]’, Skinner, Henry Devenish Papers, Hocken Archives Collection, MS-1219/160

- Photos of Chatham Island artefacts in ‘Moriori Photos’ (n.d.), Skinner, Henry Devenish Papers, Hocken Archives Collection, MS-1219/168. Stone patu, bone fishhooks, blubber cutter, stone adzes and postcard map of Chatham Islands.

- Syllabus of Evening Lectures on Ethnology 1919 & University of Otago Teaching of Anthropology (n.d.) in ‘Anthropology at Otago University’, Skinner, Henry Devenish Papers, Hocken Archives Collection, MS-1219/022

PLINTH

- Freeman, D. & W. R. Geddes, 1959. Anthropology of the South Seas: essays presented to H. D. Skinner. New Plymouth, N.Z.: T. Avery. Hocken Published Collection

- Dr Henry Devenish Skinner at the Otago Museum (1951). D. S. Marshall photograph, Hocken Photographs Collection, Box-030-013

- Dr Henry Devenish Skinner and others get aboard the ‘Ngahere’ for Chatham Islands (1924). The others are identified as Robin Sutcliffe Allan, John Marwick, George Howes, Maxwell Young and Dr Northcroft. Photographer unknown, Hocken Photographs Collection, Box-030-014

PLINTH

- The Dunedin Causeway – archaeological investigations at the Wall Street mall site, Dunedin, archaeological site 144/469 (2010). Petchey, Peter: Archaeological survey reports and related papers, Hocken Archives Collection, MS-3415/001

- Beyond the Swamp – The Archaeology of the Farmers Trading Company Site, Dunedin (2004). Petchey, Peter: Archaeological survey reports and related papers, Hocken Archives MS-2082

- A smithy and a biscuit factory in Moray Place, Dunedin… report to the New Zealand Historic Places Trust (2004). Hamel, Jill, Dr: Archaeological reports, Hocken Archives MS-2073

- Otago Peninsula roading improvements – Macandrew Bay and Ohinetu sea walls, report to the New Zealand Historic Places Trust (2010). Hamel, Jill, Dr: Archaeological reports, Hocken Archives MS-4174/001

- Album of photographs accompanying Otago Peninsula roading improvements – Macandrew Bay and Ohinetu sea walls report (2010). Hamel, Jill, Dr: Archaeological reports, Hocken Archives MS-4174/002