Post researched and written by General Assistant Gini Jory

Radical writers are often thought of as a cornerstone of New Zealand literature. Whether it be poetry, short stories, novels, commentaries or screenplays, these writers have cried out against the status quo, speaking out on issues such as racism, social injustice and numerous other political concerns. These thoughts have shaped New Zealand literature and in turn have produced a wealth of writers armed with radical prose and ideas.

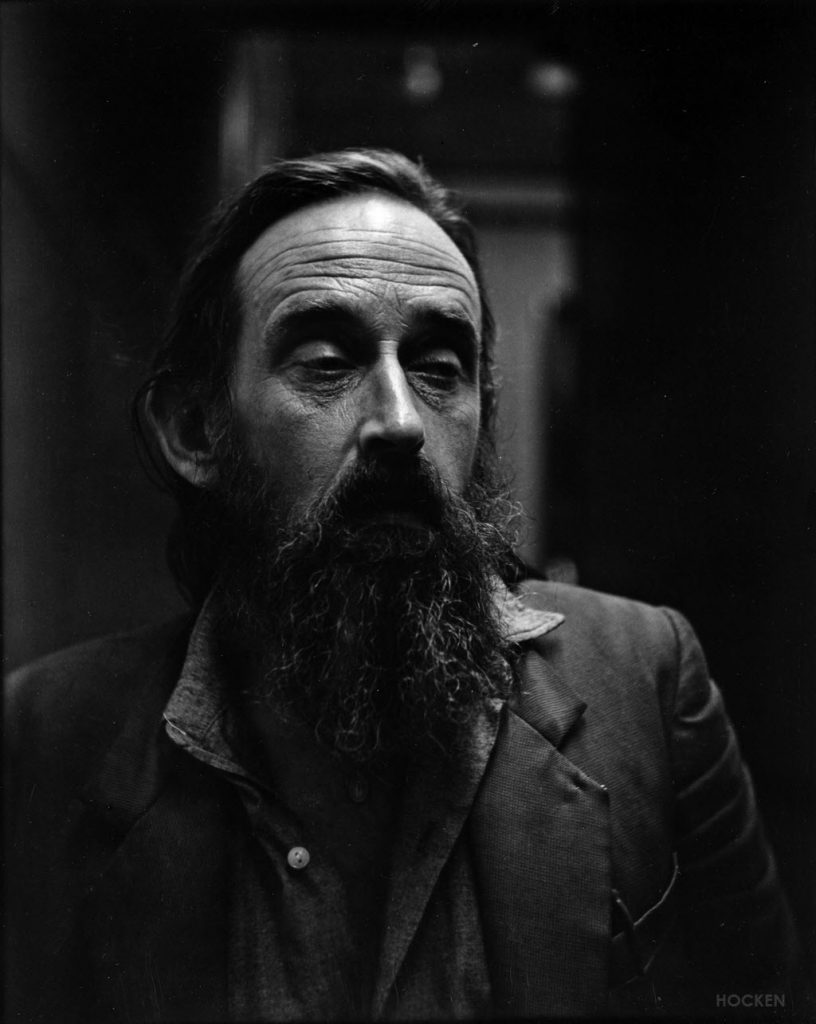

James K. Baxter, c.1965-1972. Michael de Hamel photograph, Box-005-002, Te Uare Taoka o Hākena – Hocken Collections, University of Otago.

One of the most prominent of these writers is James Keir Baxter (1926-1972) who was born into a family with established radical leanings. His father was Archibald Baxter (1881-1970), a socialist, pacifist, conscientious objector during WWI and the author of We will not cease, the memoir of his brutal experiences of forced conscription and imprisonment. The Hocken holds papers for both James K. Baxter (ARC-0027) and the Baxter family (ARC-0351) in the archives collection. Born in Dunedin, Baxter spent his formative years here, attending the University of Otago and returning later as a Robert Burns fellow in 1966. His published works cover a huge range with poetry, literary criticism and social commentaries at the forefront. He was also well known for his radical lifestyle; most notably the period in later life when he moved to Jerusalem/Hiruhārama, a Māori settlement on the Whanganui River, leaving behind his University position and job.

When thinking about potential information the Hocken might have on Baxter, you would be safe in the assumption we carry a large amount of his published works, along with the previously mentioned archival collections. However, given the radical and alternative nature of Baxter’s life and writing, this post will cover some of the more alternative, and perhaps less obvious items we carry in our collections that are equally as useful for research.

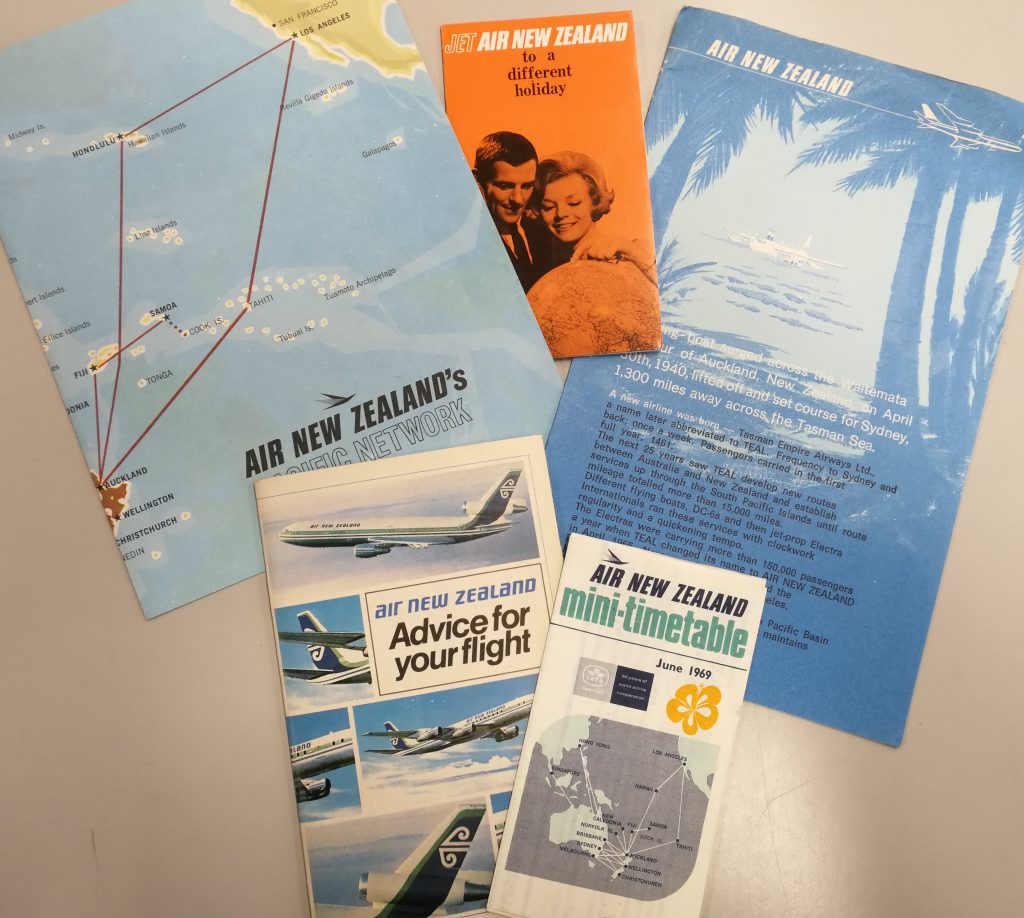

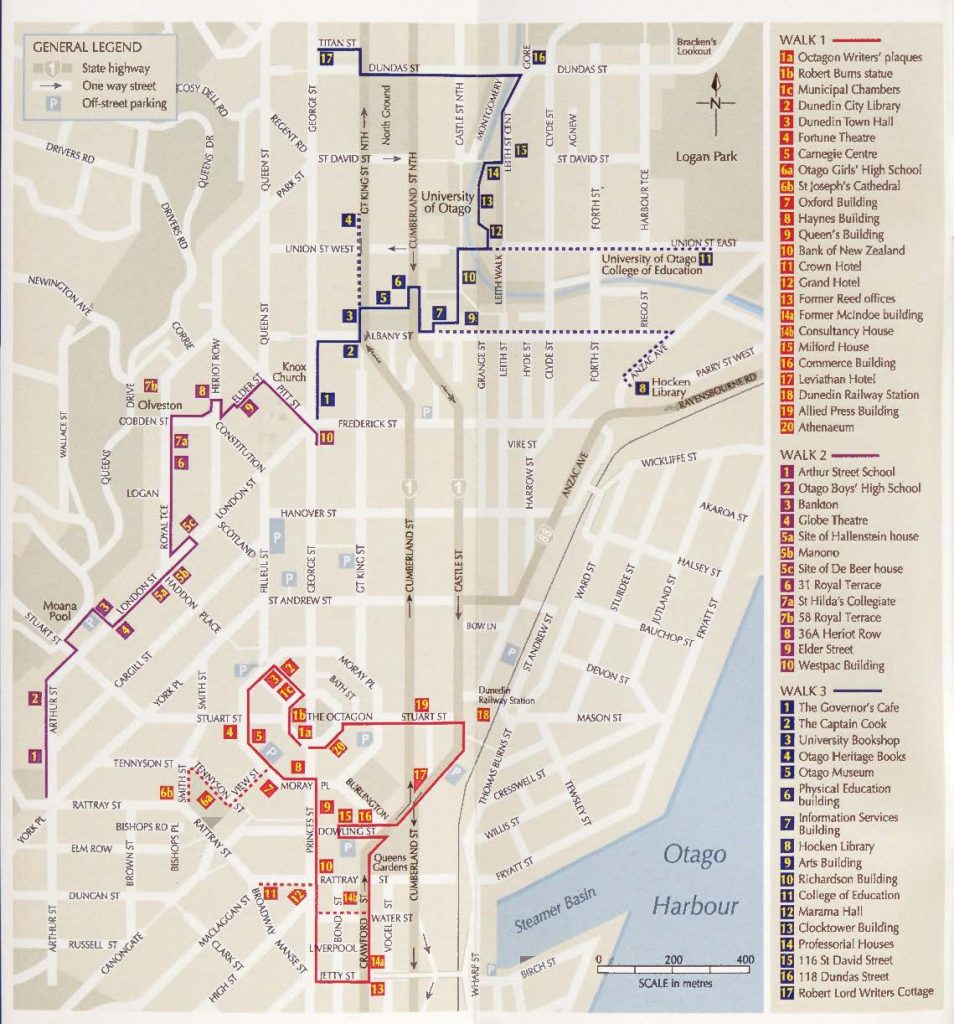

If you’re interested in taking a more active (literally!) research approach, a great place to start would be with Writers Dunedin: Three Literary Walks. Along with short biographies of many Dunedin writers, this item provides a map of three walks you can take around Dunedin, highlighting places of significance in the literary history of Dunedin and in the lives of these writers. This includes places like the Robert Burns statue in the Octagon, the Globe Theatre, the University clock tower building, as well as lesser-known places including pubs frequented by writers, schools, houses, bookshops and publishing firms. All three walks include places of significance in the life of Baxter.

Map kindly provided with permission from Southern Heritage Trust. Map design by Allan Kynaston. Barsby, John & Frame, Barbara Joan. Writer’s Dunedin: Three Literary Walks. Dunedin: Southern Heritage Trust. 2012

This publication is a companion to another item, found in our AV collection: Hear our Writers: an audio compilation of eleven Dunedin Writers. This sound recording comprises writers reading aloud their own poetry, as well as having it read by others. James K. Baxter is among these authors, and you can listen to him read his poem The Fallen House, a reflection of his early life in Brighton which he has referred to as his “lost Eden”. It is a very immersive experience to hear a poem spoken by the person who wrote it over 50 years ago, and to understand how he meant it to be heard with his own specific inflection and voice, rather than how we as readers may imagine it in our heads. This item also goes to show just how many alternative mediums there can be, and something written will not only appear in our collection as a published book or collection. We hold several other recordings relating to Baxter, further proving you can find information in the most unexpected places.

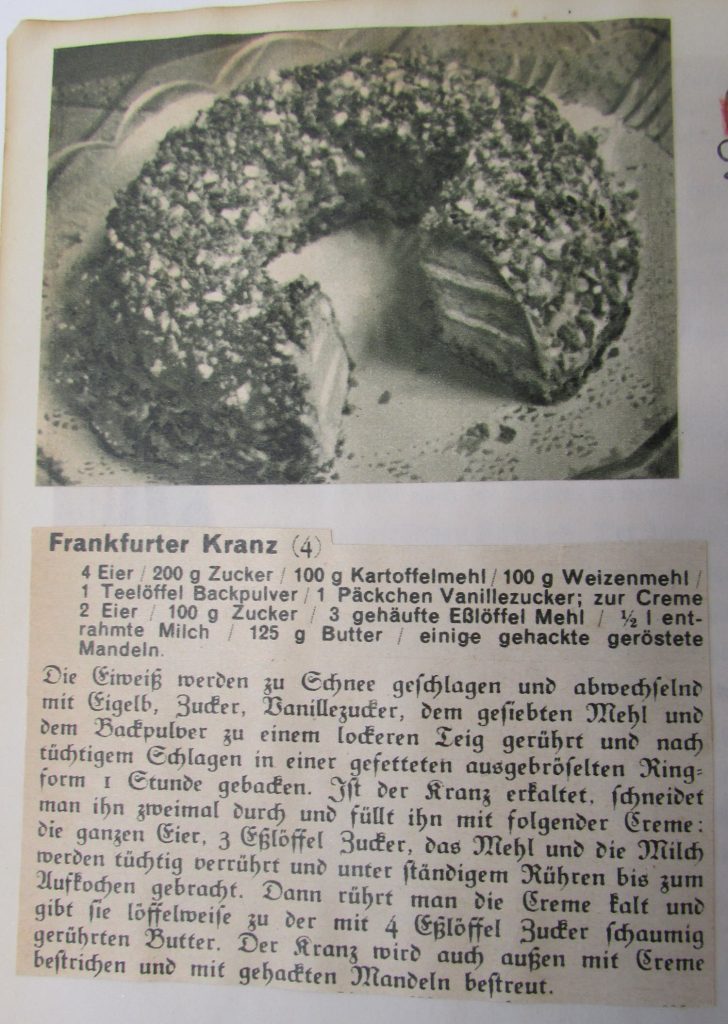

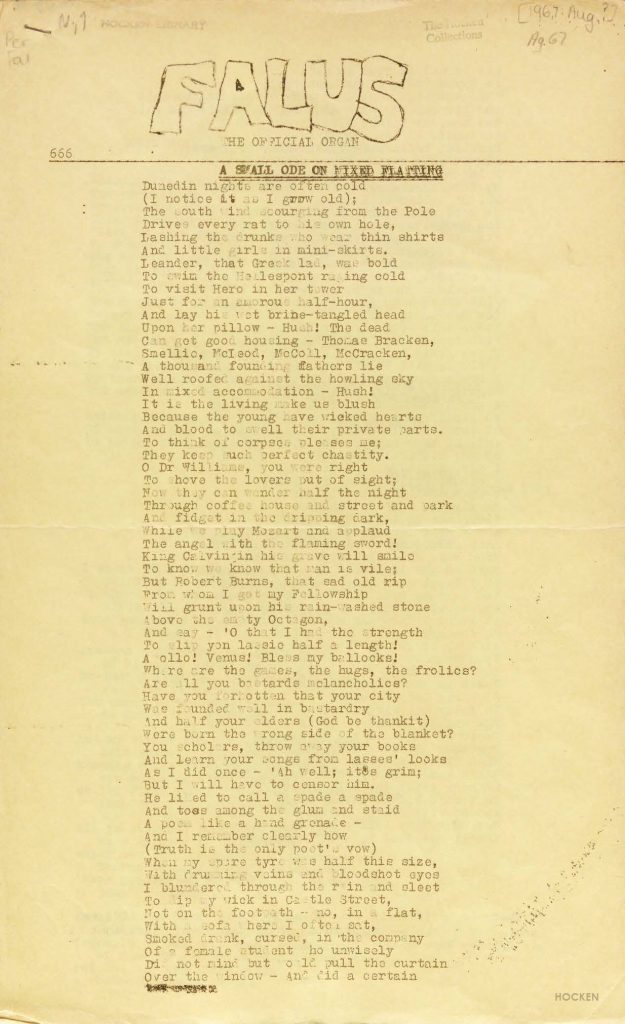

Baxter, James Keir. ‘A small ode to mixed flatting.’ Published in Falus: the official organ of the Beardies and Weirdies Industrial Union of Workers. Dunedin. 1967. (The poem continues over page.)

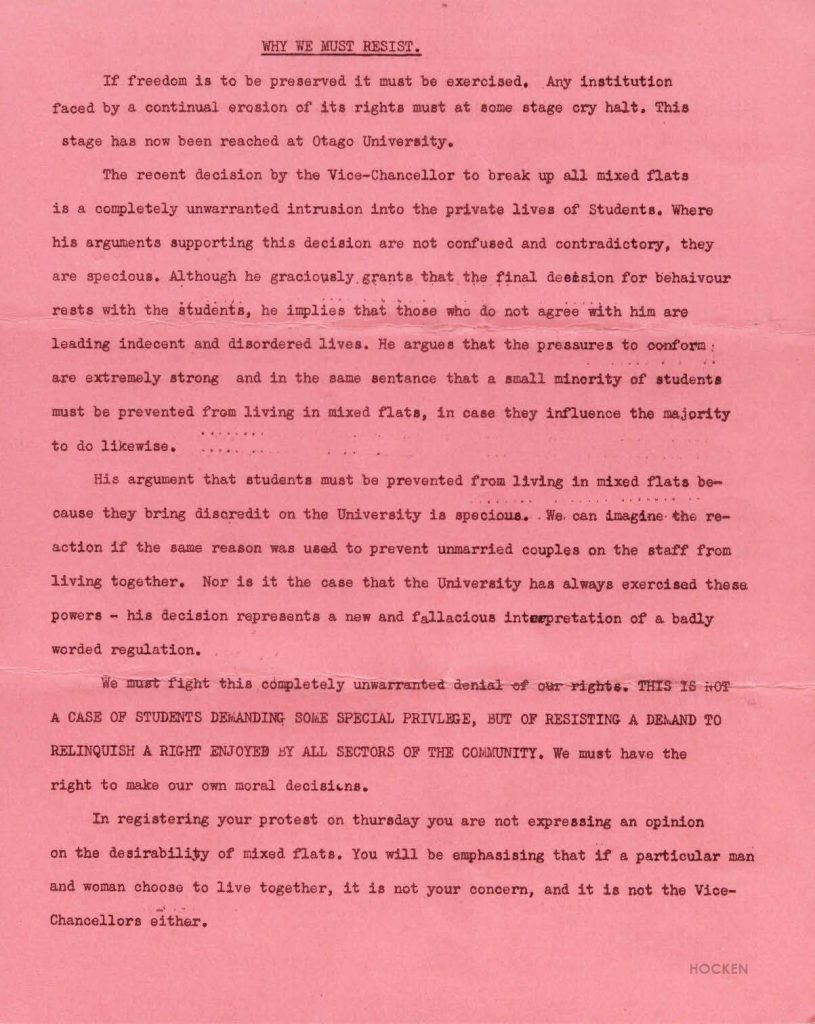

Another slightly different item we hold is an alternative student publication from Otago University, entitled Falus: the official organ of the Beardies and Weirdies Industrial Union of Workers. It was in this that A small ode to mixed flatting was originally published in 1967. This was in response to a decision made by the University to forbid mixed flatting, something that these days is seen as completely normal and out of scope of the University’s control. Critic was not interested in the story of the student expelled over this issue, so he took it to Falus instead. They approached Baxter and he agreed on the spot, providing them with A small ode to mixed flatting. This piece is an excellent example of Baxter’s alternative outlook and the importance of social activism and criticism in his life. As the Burns fellow at the time of this event, he was not a student directly affected by this decision (he was technically an employee of the University) however, he still took this opportunity to criticise the University over what many students saw as an infringement on their rights.

We have several issues of Falus, ranging from 1965-1968, featuring many poems and political letters, with a lot of satirical content (though not all stand the test of time!). Baxter has also made other contributions to this publication, including a letter about the capping show of 1967. If you are interested in student activism or political poetry, this magazine is a wealth of information and entertainment.

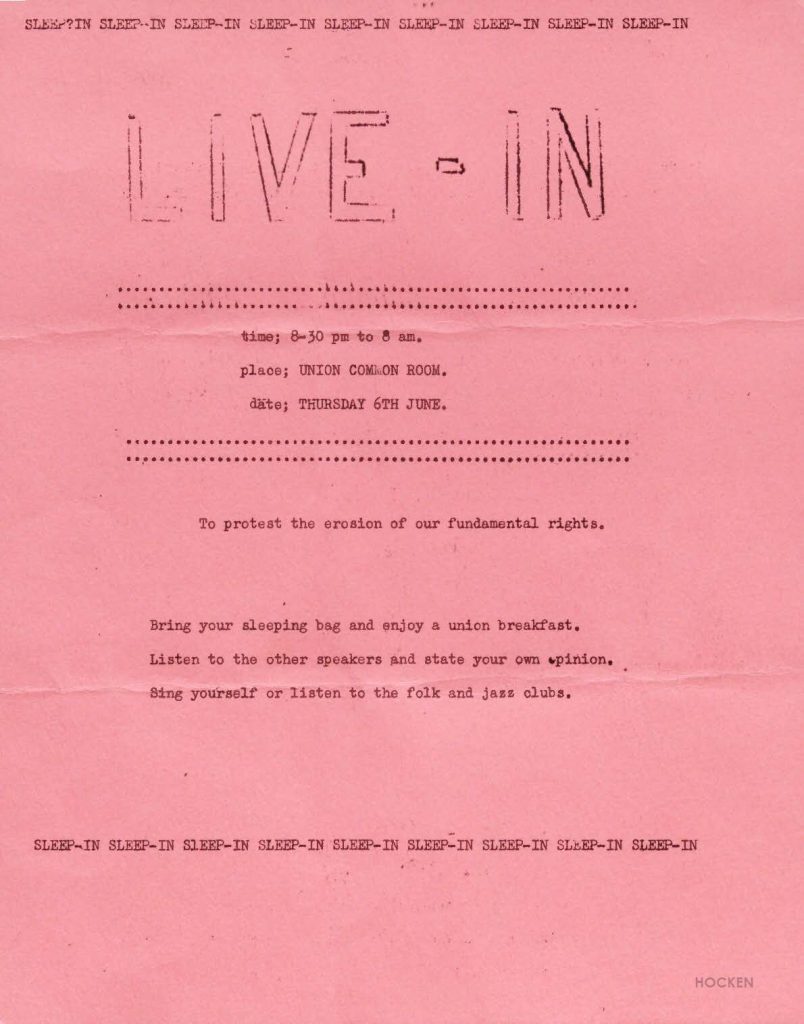

We hold other items related to this mixed flatting event, including this neat pamphlet advertising an organised sleep in, which can be found in our Ephemera collection.

Live-in. [1960s] From the Ephemera Collection, Te Uare Taoka o Hākena – Hocken Collections, University of Otago.

We have a few items relating to Baxter on display in our current exhibition, Drift– a new exhibition featuring recent Hocken art acquisitions and selected collection items. These include a photograph of Baxter rolling a cigarette taken by New Zealand art historian, writer and photographer Gordon Brown (b.1931), and a papier mâché ‘Head in a bottle’ made by Baxter in 1951/52 and deposited by his son John Baxter in 2018. Upon depositing, John wrote:

Please find enclosed the papier mâché head made by James K. Baxter as a young student at Wellington Teachers’ College. It was then a part of his desk furniture for many years, becoming a part of the internal landscape of my mother’s house after his death.

The head was much admired by my mother’s close friend the writer Janet Frame and was left to her in my mother’s will.

Sadly Janet predeceased Jacquie so the piece has come down to me as the remaining child.

I worry about its condition and would be happier if it were in a place where it could be preserved, […]

Drift is open until Saturday 17 July (Monday – Saturday 10am-5pm), so please come visit if you are interested in viewing these items in the exhibition.

When researching a famous local writer, there are plenty of obvious places to look and sources to use. Hopefully this post has highlighted some alternative sources on this topic, as well as demonstrating how the many different collections we house can be of use for all kinds of research- you might find the perfect resource in the most unexpected place!

References

James K. Baxter, c.1965-1972. Michael de Hamel photograph, Box-005-002, Te Uare Taoka o Hākena – Hocken Collections, University of Otago.

Live-in. [1960s] From the Ephemera Collection, Te Uare Taoka o Hākena – Hocken Collections, University of Otago.

Baxter, James Keir. Literary Papers. ARC-0027. Hocken Collections, Dunedin.

Baxter Family Papers. ARC-0351. Hocken Collections, Dunedin.

Baxter, Archibald. We will not cease. London: Gollancz. 1939.

Barsby, John & Frame, Barbara Joan. Writer’s Dunedin: Three Literary Walks. Dunedin: Southern Heritage Trust. 2012.

Southern Heritage Trust. Hear our Writers: an audio compilation of eleven Dunedin Writers. (Sound recording) Dunedin: Southern Heritage Trust. 2009.

Baxter, James Keir. ‘A small ode to mixed flatting.’ Published in Falus: the official organ of the Beardies and Weirdies Industrial Union of Workers. Dunedin. 1967.

Baxter, James Keir. Head in a bottle, 1951 or 1952. Papier mâché, paint, repurposed bottle. Wellington, New Zealand. Deposited by John Baxter, 2018.