Post cooked up by Andrew Lorey, Collections Assistant (Researcher Services)

I faced a daunting challenge as I started thinking about what to cook for my contribution to the Hocken Collections ‘Stirring Up the Stacks’ series. Over the last year my colleagues have fermented sauerkraut from scratch, deciphered German-language cooking notes, recreated 1960s party starters, provided a perfectly prepared peach parfait, and concocted lovely jelly-stabilised variety salads for vegans and omnivores alike.

I would describe myself as an unskilled cook at even the best of times, and as such, I struggled to think of a dish that I could contribute to a morning tea or lunchtime without subjecting my workmates to bland tastes and unpalatable textures. As you might expect, I ended up thinking about the types of foods that I enjoy, and particularly the types of dishes that my parents and grandparents cooked when I was a child growing up in America.

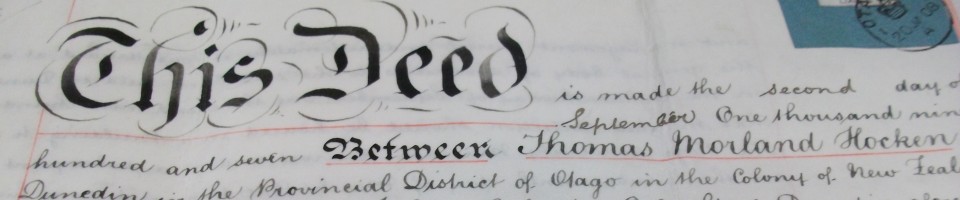

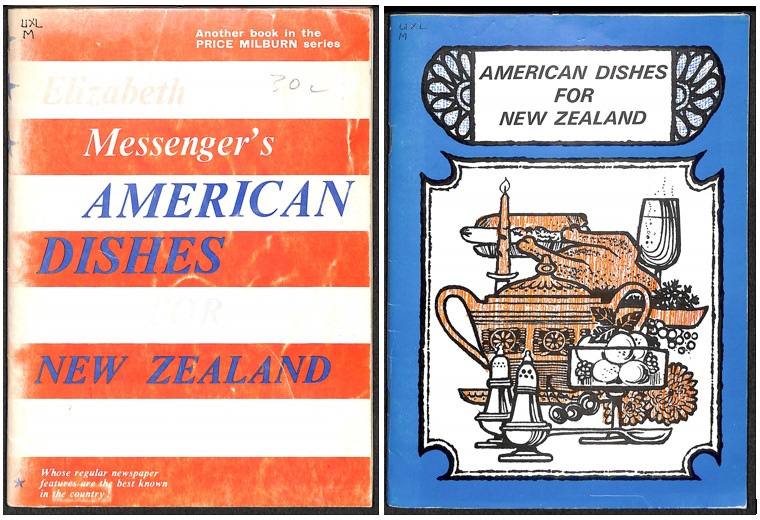

Figure 1 – Two Hocken Collections cookbooks offering recipes of ‘American Dishes for New Zealand’.1, 2

Different Cultures and Different Cuisines

It is an indisputable fact that all of us have our own personal favourite foods, whether they come in the form of hāngī, vegetarian dishes featuring perfectly cooked tofu or after-dinner treats like ginger nuts and vanilla ice cream. But food plays a much more important role in our lives than simply providing us with nutritional nourishment and energy. I think Emma Johnson captures the multi-dimensional importance of food in her introduction to Kai and culture: Food stories from Aotearoa:

Food is a confluence of things: a web of weather systems; the lay of the land; stories of arrival, trade, economics and politics; histories and empires; domestic and urban practices. It is all connected and culminates in each of us. All of these systems, stories and politics become deeply personal, as food becomes part of us.3 (emphasis added)

In an increasingly global world, it may come as no surprise that people are consuming increasingly global foods. Recent census statistics published by Stats NZ Tatauranga Aotearoa show that 27.4 per cent of the people residing in New Zealand during the 2018 Census were born outside of the country4, and it follows that most New Zealand immigrants have transported their home countries’ cuisines along with them. When reflecting upon my own identity as an immigrant, I realised that it would be interesting to search for cookbooks at the Hocken Collections that provide instructions for dishes that may not traditionally be associated with New Zealand.

Figure 2 – This adaptation of a figure published by Stats NZ Tatauranga Aotearoa illustrates the proportions of New Zealand immigrants as reported during the 2018 Census.5

I am pleased to say that I did not have any trouble finding cookbooks related to the immigrant experience here at the Hocken Collections. Interestingly, I found a series of cookbooks published by Wellington’s Price Milburn publishing house between the late 1950s and early 1970s that provided recipes from a wide variety of international cuisines. The two American recipe books shown in Figure 1 come from this Price Milburn series, but the publisher also included volumes dedicated to Chinese, Turkish, French and South East Asian dishes.

Figure 3 – Wellington-based publishing house Price Milburn published a series of cookbooks catering to international tastes between the late 1950s and early 1970s.6, 7, 8, 9

Although it is uncertain whether actual New Zealand immigrants were involved with the creation of this Price Milburn series or whether the recipes were put together by New Zealanders who were simply interested in international cuisines, it is clear that an appreciation of international flavours and food literature has persisted in the decades following the Price Milburn publications. For example, recent books like Lift the Lid of the Cumin Jar10, Me’a Kai: The Food and Flavours of the South Pacific11 and “Dinner at my place”: The great Refugee and Migrant cook book12 celebrate and explore the many layers of meaning that exist within the flavours of immigrant experience.

Bringing together dishes from countries as diverse as Rwanda, Chile, Sweden, Vietnam and Vanuatu, books such as these showcase the many vibrant culinary cultures that exist both inside and outside New Zealand while also telling the stories of particular people from particular places. As Therese O’Connell states in her introduction to Lift the Lid of the Cumin Jar, “food, the preparation and sharing of it, consistently plays a fundamental role in each of the cultures we encounter.” It was precisely this fondness for sharing that led me to prepare a dish that pays homage to the culturally American cuisine that I grew up with – the not-too-savoury and not-too-sweet pumpkin pie.

As American as… Pumpkin Pie?

Pumpkin pie is a popular American dessert during autumn, particularly during the months of November and December, when many people observe holidays like Thanksgiving (the fourth Thursday of November) and Christmas. During my recipe search, I consulted three separate cookbooks that included recipes for pumpkin pie in a quest to discover the finest list of ingredients and the most fool-proof instructions. Although one of the recipes came from a ‘foods demonstration’ undertaken by the University of Otago Department of University Extension13, I ultimately decided to use a recipe for ‘Hot Pumpkin Pie’ that appeared in one of the Price Milburn booklets shown in Figure 1.

Figure 4 – American recipes for Thanksgiving, including the instructions used for the ‘Hot Pumpkin Pie’ eaten recently at the Hocken Collections.

Hot Pumpkin Pie

8 oz [227 g] flour

2 oz [57 g] butter

2 oz [57 g] lard

½ teaspoon salt

cold water

1½ cups [368 g] mashed cooked pumpkin

2 eggs

6 oz [170 g] brown sugar

¼ teaspoon grated nutmeg

½ teaspoon cinnamon

½ teaspoon ground ginger

1 cup [237 ml] milk

1 teaspoon grated lemon rind

METHOD:—Sift flour with salt and rub in butter and lard. Cut in just sufficient cold water to bind to a stiff paste. Turn out and roll and line a pie plate with one inch overlapping. Turn overlapping edge under. Prick the bottom and bake for ten minutes in a fairly hot oven, then fill and return to bake for a further three-quarters of an hour in a more moderate oven, until the filling is set and browned. To make the filling, steam pumpkin until tender and sieve enough to make 1½ cups puree. Beat in eggs, brown sugar, spices, and milk. Turn into pie shell and dust with additional nutmeg.

As you can see, the recipe provides instructions for making both the pie crust (using the first five ingredients) and the filling (using the final eight ingredients). The instructions do, however leave some things open for interpretation when it comes to the quantity of cold water necessary to create the perfect crust and the cooking temperatures that should be used in the oven (I could not locate settings for ‘fairly hot’ or ‘more moderate’ on my oven at home…). Where possible, I have calculated metric conversions for the ingredients and included those above.

Although the recipe does not explain this portion of pumpkin pie preparations, I began my cooking by washing my pumpkins under cool water, slicing them in half, scooping out the seeds and roasting them for about 60 minutes at 170˚C. To decide whether they were ready to be sieved, drained and pureed, I tried to pierce their rinds with the tines of a fork.

Waiting for your pumpkins to soften in the oven provides ample time to make the pie crust, although I must confess that I had saved some pre-made shortcrust in the freezer for this occasion. If you have a tried-and-tested family recipe for pie crusts, then you should feel free to use that too!

After pre-baking your pie crust if you wish (see the recipe method above) and creating your pumpkin mash puree, then the rest of the recipe is quite straightforward. Just beat in eggs, brown sugar, milk and spices (I doubled the suggested amounts of nutmeg, cinnamon and ginger), fill up your pie crust with this mixture and then cook for about 60 minutes (or until a knife inserted into the centre comes out clean) at 175˚C.

Figure 5 – One of the two pumpkin pies cooked as part of this instalment of ‘Stirring Up the Stacks’.

Reactions from colleagues about the pumpkin pies that I prepared were generally favourable, although several comments did remark that sweet pumpkin dishes remain somewhat foreign to the New Zealand palate:

“Transcendent”

“Delicious! A lovely blend of spices”

“Texture was a fluffy dream!!”

“Is it a main? Is it dessert? Could be both. All day eating.”

“I still find the concept of pumpkin as a sweet dish hard to wrap my head around, but this pumpkin pie was delicious!”

“Best pumpkin pie!”

“Yum!”

It seems fitting that this blog post has been published only shortly after Thanksgiving, and I hope that many of you who read it decide to give this recipe a try!

Figure 6 – I think one of my colleagues put it best when she said, “Yum!”.

[1] Elizabeth Messenger’s American Dishes for New Zealand (1962). Wellington: Price Milburn & Company Limited.

[2] American Dishes for New Zealand (n.d.). Wellington: Price Milburn & Company Limited.

[3] Johnson, Emma (2017). Kai and culture: Food stories from Aotearoa. Christchurch: Freerange Press.

[4] Stats NZ Tatauranga Aotearoa (2019). 2018 Census totals by topic – national highlights. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/2018-census-totals-by-topic-national-highlights[5] Stats NZ Tatauranga Aotearoa (2019). New Zealand as a village of 100 people. https://www.stats.govt.nz/infographics/new-zealand-as-a-village-of-100-people-2018-census-data[6] 50 Chinese Dishes you can make (1958). Wellington: Price Milburn & Company Limited.

[7] Harris, Patricia (n.d.). Fit for a Sultan: Turkish Food for Other Kitchens. Wellington: Price Milburn & Company Limited.

[8] French Dishes for New Zealand (n.d.). Wellington: Price Milburn & Company Limited.

[9] Heuer, Berys (n.d.). South East Asian Dishes for New Zealand. Wellington: Price Milburn & Company Limited

[10] Reid, Robyn (1999). Lift the Lid of the Cumin Jar: refugees and immigrants talk about their lives and food. Wellington: Wellington ESOL Home Tutor Service Inc.

[11] Oliver, Robert (2010). Me’a Kai: The Food and Flavours of the South Pacific. Auckland: Random House New Zealand.

[12] Refugee and Migrant Service (1998). “Dinner at my place”: The great Refugee and Migrant cook book. Lower Hutt, N.Z.: Refugee & Migrant Service.

[13] University of Otago Department of University Extension (n.d.). Ideas from Overseas American Food. Foods Demonstration. Dunedin: University of Otago.

What else have we cooked up?

Stirring up the stacks #5: – sauerkraut roll

Stirring up the stacks #4: a “delicious cake from better times”

Stirring up the stacks #3: Bycroft party starters

Stirring up the stacks #2 The parfait on the blackboard

Stirring up the stacks #1 Variety salad in tomato aspic