Post researched and written by Anna Petersen, Curator Photographs

Figure 1 Barranquila, Colombia, South America, 1906. P1991-023/01-2222

The Hocken holds the definitive archive of works by English-born photographer, George Chance (1885-1963). The collection encompasses all aspects of his output from original prints, negatives, and colour slides, to proofs, albums, correspondence, sound recordings, written notes and published reproductions in the form of newspaper and journal illustrations and calendars.

Photograph historian, William Main, drew extensively on this resource when compiling a chronology of Chance’s life and researching his catalogue essay for the Dunedin Public Art Gallery exhibition George Chance: Photographer in 1986. That touring exhibition catalogue remains the main publication on Chance’s work and his influence on New Zealand photography, though others have also contributed to the literature since then.[i]

This blog serves to illustrate and probe a little deeper into one particular chapter of Chance’s life that Main only mentions in passing. Pieced together primarily from Chance’s own written and recorded accounts, spoken with his fruity London accent, the surprising tale reveals something of Chance’s adventuresome spirit before he ever reached New Zealand and draws attention to images of more international interest that are housed in the Hocken Photographs Collection.[ii]

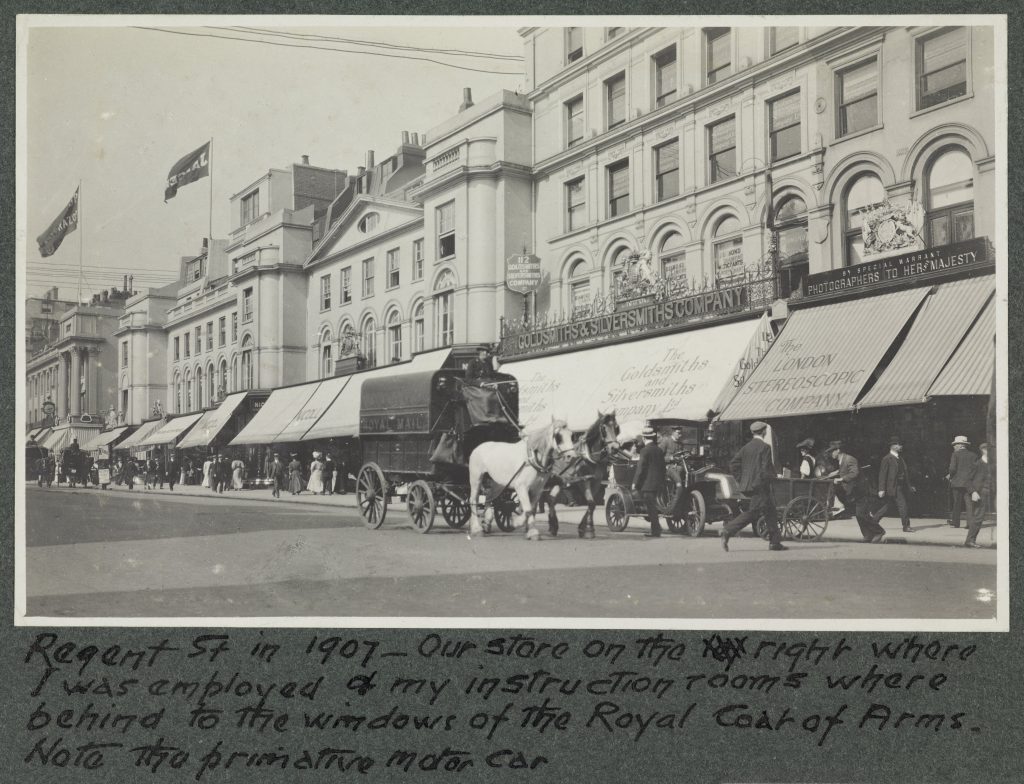

The story began in December 1905. Young ‘Chancey’, as his friends called him, was working in Regent Street at the time, for the prominent London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company. He held the position of demonstrator/instructor, showing how the latest cameras and photographic equipment operated to all manner of aristocrats, explorers and famous people.

Figure 2 Regent Street, 1907. Album 544, P2007-014/1-040a

One day a very tall man with a beard walked in and pledged to buy a complete set of movie and still cameras if the firm provided a man to accompany him on a trip and act as photographer and secretary. It promised to be a valuable commission so ‘Marmalade’ the salesman, offered ‘Chancey’ £5 to apply for the job. Chance obviously felt up for the challenge because that Monday he went along for an interview with the mysterious customer, who turned out to be the eccentric English hunter and adventurer, John Talbot Clifton (1868-1928). Talbot Clifton reputably made a habit of sampling the wild animals he came across (including a mammoth found in the Arctic permafrost).[iii]

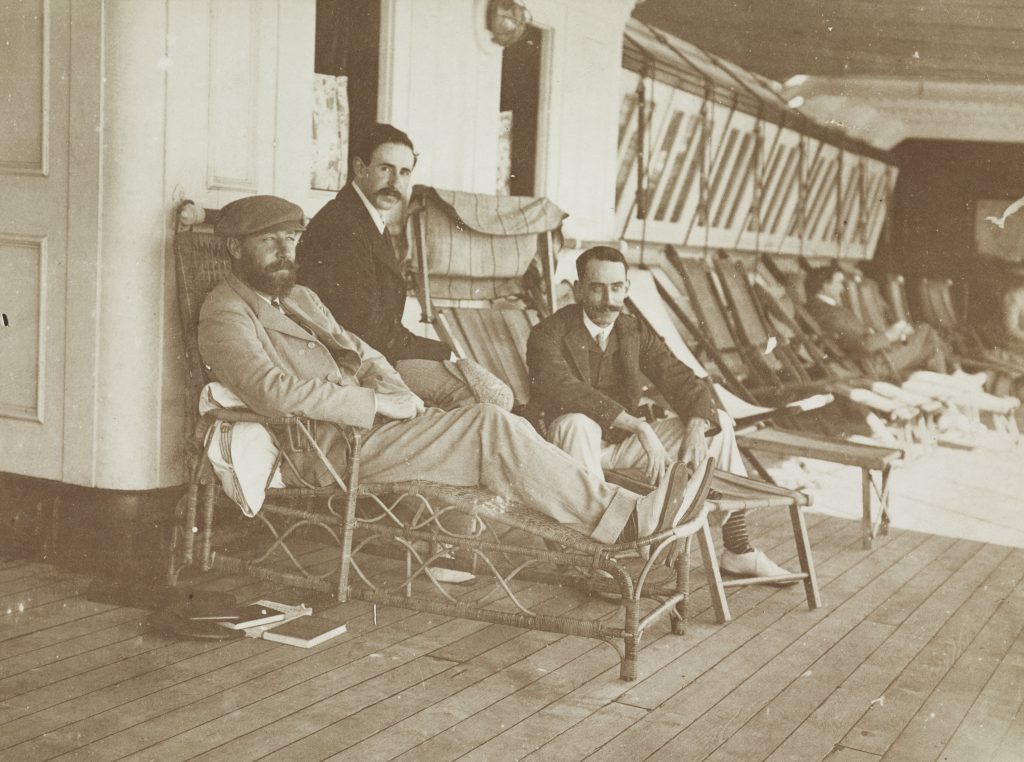

Figure 3 John Talbot Clifton, 1905. P1991-023/01-0499

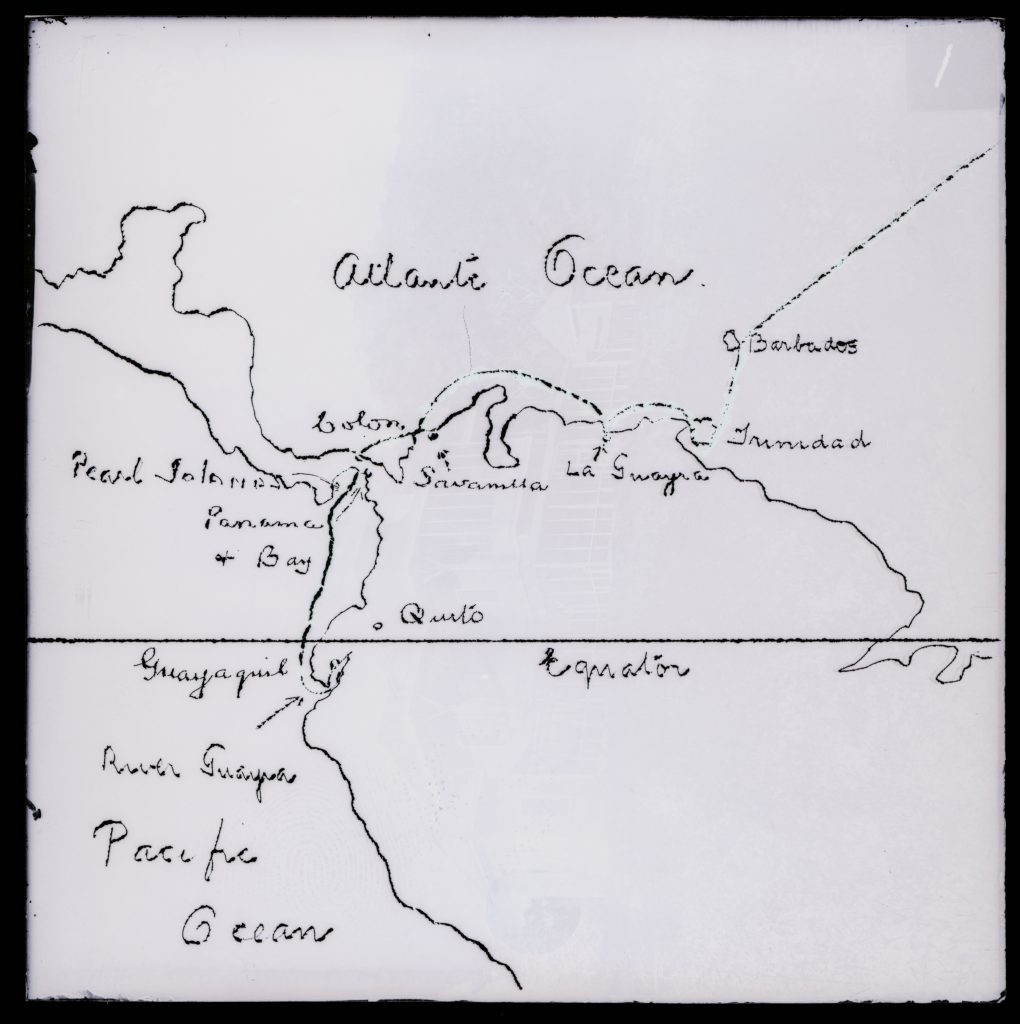

Talbot Clifton thought George looked a bit young, but George (who was only 19 at the time), reassured him that he wasn’t as young as he looked and he got the 15-month contract, on condition that he got himself a tropical kit and made the ship by Saturday. His father wasn’t too thrilled, and nor were his employers, but George managed to wrangle it and soon found himself in charge of about 30 parcels of guns and supplies, boarding the SS Atrata at Southampton on Christmas Eve. It wasn’t until several days into the voyage that he learned that they were bound for Cocos Island, situated in the Pacific Ocean, off the coast of Costa Rica. They were on a quest in search of lost Spanish gold. As one of several newspaper articles on the subject pasted into the back of Chance’s diary states, there were two alleged buried hoards on the island: ‘one, a pirate treasure, is valued at between six and twelve millions sterling, and the other – known as “Keatings treasure” – is said to be worth three millions’.[iv]

Figure 4 Map of the voyage, n.d. Lantern slide, P1991-023/03-032

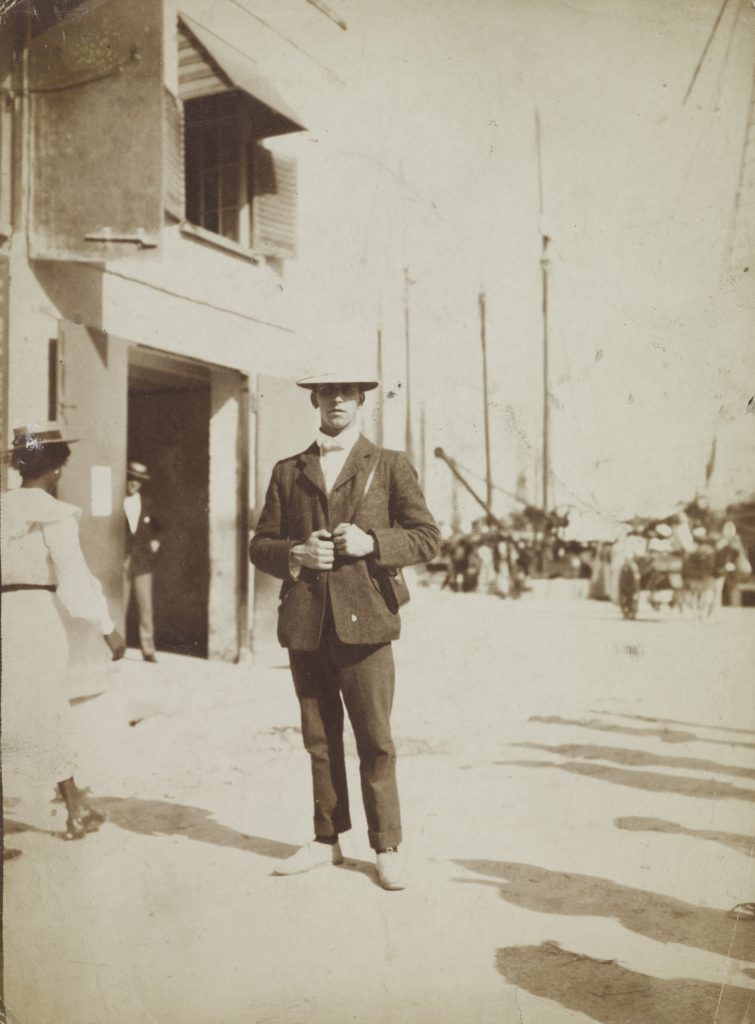

After a rough trip across the Atlantic, the party made a number of stops in quick succession along the upper coast of South America; the first at Barbados on 4 January, where Chance got a photograph of himself in Georgetown, apparently dressed for the part.

Figure 5 George Chance in Georgetown, Barbados, 1906. Photographer unknown, P1991-023/01-0582

Moving on via Trinidad to Venuzuela, Chance was let off at the country’s main port of La Guaira on 7 January for four hours and told to get some native studies. What his boss neglected to mention was just how politically unstable the region of Central America was during this period and as Chance recalled, he did not venture further than the pier.

A third stop-off in Colombia proved more fruitful from a photographic point of view (figures 1 and 6). Chance recorded in his diary how he ‘Wandered about the streets [of Barranquilla] + admired the peculiar thatched houses. Streets were very quiet + nearly all shops closed as folk we[re] having afternoon snooze. Got some interesting photos…’.[v] There the danger seemed to lie in Savanilla Bay where they observed five wrecks.

Figure 6 Natives and home in Colombia, South America, 1906. P1991-023-2344

The next day at Colon, Chance took some rather boring snaps if those in the Hocken Collections are anything to go by. As he noted in his diary ‘Colon looks an awfully desolate + dreary place, had a big fire there recently so that best part of town is in ruins’.[vi] From Colon they took a train to Panama, where they found another large fire still raging and Chance almost got his camera saturated with water by a fireman’s hose. The real danger, however, was of a different nature as deaths from Yellow Fever saw work on the canal come to a halt. Still, they had to wait around for the President of Ecuador, General Leonidas Plaza Guierres, to join them on the ship before sailing south to Quayaquil.

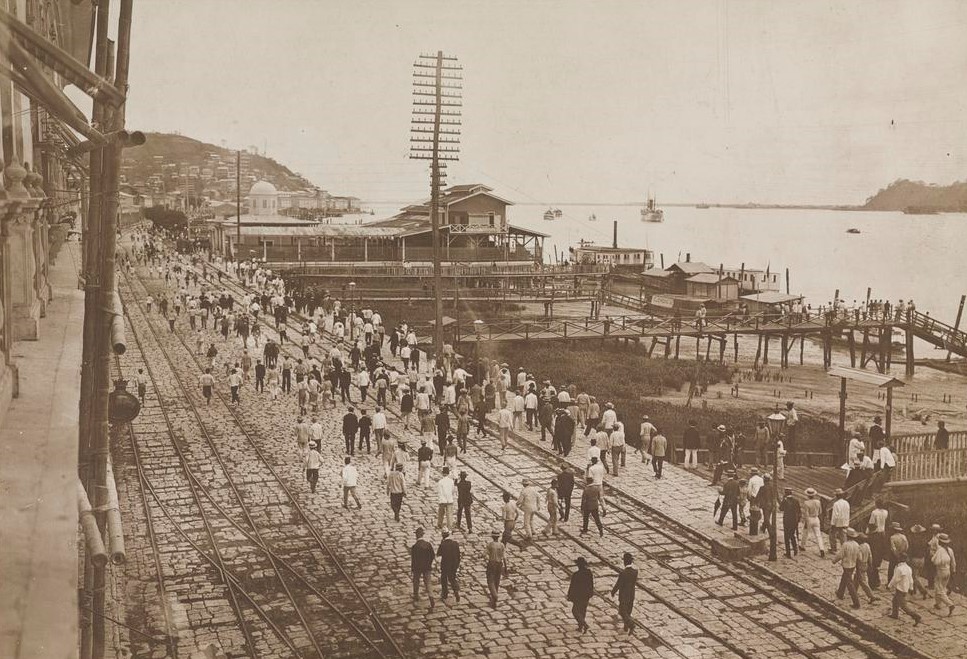

Talbot Clifton and his advisors had chosen Quayaquil in Ecuador as the supply base for the expedition to Cocos Island because of the prevailing winds, but the city would prove another hot bed of political unrest. In an account later published in the Otago Daily Times in 1932, Chance related all the details of his conversation with General Guierres on board ship, which indicated that the leader had no real idea of the gravity of the situation. Far from saving the day and having his troops photographed by Chance as planned, he was welcomed at Quayaquil by a horde of revolutionaries led by Eloy Alfaro and the President narrowly escaped about a week later with his life.[vii]

Figure 7 Crowd of citizens from Guayaquil meeting the boat loads of revolutionists arriving to join in the revolution, January 1906. P1991-023/01-2353

Figure 8 Revolutionists arriving by boats at Guayaquil, Ecuador, January 1906. P1991-023/01-2349

Exactly how much at risk the expedition party ever was at during the revolution is a little hard to gauge. Chance wrote in a letter to his parents on 19 January from the Gran Hotel Paris:

Our ship arrived here yesterday morning. The town is not on the sea coast as I at first thought but some miles up a very wide river, it is one of the finest towns on the whole of the S. America coast + we have put up at the very best hotel. Mr C. has two rooms + I have a nice room to myself overlooking the river. This is the order of the day. Coffee is served from 7am to 9. Breakfast 10.30 to 12.30 Dinner 5.30 up to 8.0[.] Some of the dishes are rather curious + want getting used to but I make a point of eating plain food + plenty of fruit + this I find agrees with me very well.[viii]

We know that Chance did not want his family worrying and tensions did escalate. The letter is unfinished and his diary entry for the same day reads ‘For hours bullets were passing our windows + striking the tin roofs…’.[ix]

There was definitely some fierce street fighting during the night when at least 150 people lost their lives and Chance undoubtedly had one or two nasty frights during his stay at Guayaquil. Inscribed photographs provide evidence of some of the worst scenes that Chance encountered when he eventually ventured out of his room with his new friend, Captain Voss. He noted on the back of the photograph in figure 9:

Bullet holes on plaster. Capt. Voss is the centre right figure[.] In this native square were many dead bodies mostly the result of hand to hand fighting with knives – I was violently sick at the sight + because of any native reaction when I might have been knifed on the spot I did not attempt further photographs – 200 were killed that night.

Figure 9 After the revolution, 1906. P1991-023/01-2354

Captain John Voss was another colourful character who had already acquired fame by this time for a journey he made around the world in a dug-out canoe called the Tilikum and joined the party in Quayaquil with the job of leading the treasure hunt.[x]

Sadly the treasure-hunting aspect of the adventure ended in disappointment. Chance tells of how they purchased a 50 ton barque at Quayaquil and sailed to Cocos Island (also famous for its shark-infested waters).[xi] They stayed only a very short time and had to abandon any further plans because of the fighting and rampant fever. In other words, the Talbot Clifton expedition, became just another of the many failed attempts to locate gold on the island over the years, though the place continues to capture people’s imaginations in fictional accounts, from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island to Michael Crighton’s Jurassic Park.[xii]

Back in Quayaquil, things literally began to fall apart. Chance was developing some photographs when an earthquake struck and the front of his room fell down into the street. According to Violet Talbot, who later wrote in an account of her husband’s life after his death (en route to Timbuktu!), ‘news came that the Chilean Government would not allow any more expeditions to Los Cocos. Talbot had to pay off his men who were glad to be freed, for they had had their fill of danger. The outbreak of yellow fever and the revolution were followed by more earthquakes’.[xiii]

Clifton Talbot decided to do a little exploring instead, hoping amongst other things, to find the source of the Amazon. According to Chance, he was not allowed to follow because he was under 21, so he decided to do a little exploring of his own. Chance did not leave precise details of this part of the journey but he suffered intermittent fevers from malaria that he had contracted in Barbados and ended up in the canal zone where he stayed for several months before returning to England.

Chance was welcomed back into his old job in London, now the company’s expert in the specialised field of tropical photography. (They had tried photographing wild animals at night in Central America with the aid of a primitive kind of flash powder, but Chance didn’t like it much and it was more exciting than successful. Apart from anything else ‘there were some nasty little snakes, which looked like branches of trees, which if they bit you, well, it was good night’).[xiv] Most notably, Winston Churchill would come for several afternoon lessons in preparation for his tour of East Africa in 1907. This contact caused Chance to fear for his position, as Winston forgot to roll on his films and when given the job of developing the precious negatives, Chance had to front up with 200 blanks.

Chance was always ambitious and eighteen months later, he put aside photography for a while and trained to be an optician – a profession that would eventually lead to a job on the other side of the world in Dunedin in 1909. On leaving the British Stereoscopic Company, the General Manager commended Mr George Chance, Junior for being a ‘good salesman attentive to his duties, punctual and excellent manners and address’ and that he had ‘assisted in various outdoor expeditions requiring smartness and ability’.[xv] I dare say, not all of the outdoor expeditions were quite as dangerous and exciting as the Cocos Island mission.

Although the expedition to Central America failed to produce the great riches the Talbot Clifton party had dreamed about, Chance did manage to save £300 while he was away, which left him a young man of means, with a fine story to dine out on for the rest of his life. In a way, the surviving photographs are the real treasure, available now to everyone in the Hocken Collections, thanks to the generosity of the Chance family.

References

[i] See Linda Tyler, George Chance: Improving on Nature, exhibition catalogue, Gus Fisher Gallery, University of Auckland, 2006 and David Eggleton, Into the Light: A History of New Zealand Photography, Nelson, 2006, pp. 49-50.

[ii] Thank you to David Murray for providing copies of the sound recordings in Hocken Archives, MS-5119 and to Sarah Fairhurst for her suggestions. All figures taken by George Chance, unless otherwise stated.

[iii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Talbot_Clifton (accessed 29/11/2021).

[iv] ‘Island’s Vast Treasures. Admiral Palliser and New Cocos Expedition. Doomed to Failure’, Daily Express, 2 April 1906.

[v] George Chance, Diary, 9 January 1906, MS 3158/142.

[vi] Ibid., 10 January 1906.

[vii] ‘General Guierrez Ups and Downs of a President’s Life: Dunedin man recalls revolution in Ecuador’, Evening Star, 21 September 1932.

[viii] George Chance, Letter to parents, 19 January 1905 [sic], MS-3176/005.

[ix]Diary, 19 January 1906.

[x] See J.M. MacFarlane and L.J. Salmon, Around the World in a Dugout Canoe: The Untold Story of Captain John Voss, Canada, 2020 for Voss’s own account of the conflict at Guayaquil, as well as details of Voss’s previous trip to Cocos Island and other photographs relating to the Talbot Clifton expedition – which include George Chance (though wrongly identified).

[xi] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cocos_Island (accessed 29/11/2021).

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] V. Clifton, The Book of Talbot, London, 1933, p.280.

[xiv] Chance reel 4, 26.49-55, MS-5119. No examples of these animal photographs are included in the Hocken Collections.

[xv] Letter of commendation, 23 October 1907, MS-3158/142.