Nā Jacinta Beckwith, Kaitiaki Mātauranga Māori

This year Te Wiki o Te Reo Māori coincides with #MahuruMāori – a reo challenge to speak Māori for the month of September. Here at Hocken and across the Libraries we continued with our kaupapa from recent years to promote rangahau Māori and this year we especially highlight Postgraduate Māori research in displays and in Postgraduate Māori research presentations at Hocken.

This morning at our opening event, we were treated with a fantastic kōrero from Te Koronga Researcher Ngahuia Mita. Ngahuia graduated with a Master’s degree in Physical Education with distinction from the School of Physical Education, Sport & Exercise Sciences last year, and then travelled to Antarctica with Professor Christina Hulbe, Kelly Gragg and Michelle Ryan under the Ross Ice Shelf Programme. Ngahuia’s kōrero was complemented by the launch of an exhibit in the Hocken Foyer celebrating Māori and Polynesian voyagers to Antarctica, displaying a range of Antarctic resources from the Hocken Collections.

Tawhana kahukura i runga, ko Hui-te-Rangiora te moana i tere ai

The rainbows span the heavens whilst Hui-te-Rangiora speeds over the oceans

Celebrating Māori and Polynesian Voyagers to Antarctica

Hui-Te-Rangiora

Rarotongan narratives and traditions of Ngāti Rārua and Te Āti Awa tell the story of a Polynesian explorer, Hui-Te-Rangiora, or, Ui-Te-Rangiora, the first to travel to the Antarctic around 650 AD. Hui-Te-Rangiora returned with stories of icebergs, naming the land: “Te Tai-Uka-a-Pia”meaning “sea foaming like arrowroot” comparing the similar characteristics of the starchy scrapings with the sheets of floating ice and snow.

Hui-Te-Rangiora remains remembered and honoured as he sits atop the whare tūpuna (ancestral house) Tūrangapeke at Te Awhina marae in Motueka, and atop the waharoa (gateway) at the entrance to Te Puna o Riuwaka (the Riuwaka Resurgence), a place he is said to have taken rest preparing himself spiritually and physically for the epic voyage to the Southern Ocean.

Tuati

The first New Zealander to enter Antarctic waters was a Māori man named Tuati, a crew member aboard the Vincennes during Lieutenant Charles Wilkes’ United States Exploring Expedition of 1839-1840. Son of a Scottish whaler Captain William Stewart and his Ngāpuhi wife, Tuati was also known as Te Atu, John Sac and John Stewart.

Tuati worked both as a seaman and as an interpreter, accompanying Wilkes when the expedition stopped in French Polynesia. In his narrative of the expedition, Wilkes describes “Tuatti” as “an excellent sailor, a very good fellow”.

The New Zealand Geographic Board commemorated Tuati’s first sighting of Antarctica by naming a peak after him in Antarctica’s Royal Society Range 150 years later.

Dr Louis Hauiti Potaka

Captain A. L. Nelson, commander of the Discovery II., welcoming Dr Potaka on embarking aboard the Discovery, en route to Little America, where he will take the place of Dr G. Shirey as medical officer to the Byrd Expedition. Evening Star, 15 February 1934, page 2, Hocken Newspapers Collection

Louis Hauiti Potaka, born at Utika, Whanganui in 1901, was the fifth Māori medical graduate in New Zealand and served as doctor for Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd’s second Antarctic expedition in 1934-1935.

Potaka studied medicine at the University of Otago from 1920-1929, graduating with his MBChB in 1930. Following graduation, he worked at Nelson Public Hospital and in Murchison. When the Byrd expedition’s original doctor was unable to winter over in Antarctica, a call went out for a replacement doctor and Potaka was selected.

In February 1934, Potaka boarded the Royal Research Society’s Discovery II, which called into Port Chalmers especially to pick him up. The vessel took him to rendezvous with the rest of the team on the Bear of Oakland in the Ross Sea before their four-day journey through pack ice to ‘Little America’.

While in Antarctica Potaka performed an emergency appendectomy, extracted teeth, conducted health checks on the team and dealt with a broken arm and frostbite. Non-medical activities included chess, movies and digging in the ice for buried items from Byrd’s first expedition, 1928-1930.

On his return to Dunedin via Byrd’s supply ship Jacob Ruppert in February 1935, he said he had enjoyed his experience but was glad to be back.

Potaka then went back to Nelson to work as a locum and Native Medical Officer for Dr Edward Coventry Bydder but the arrangement did not go well. He left to set up his own practice with support from the local community, but British Medical Association rules instructed him to leave the district to practice elsewhere. His vision was also deteriorating due to ultraviolet keratitis (snow blindness), a condition he developed while in Antarctica, and made worse by its remedy at the time – cocaine drops. His failing eyesight and unhappiness at work weighed heavily on him, leading to depression and his premature death by morphine overdose.

Two years later, his mother received the US Congressional Medal in appreciation of her son’s work for the Byrd expedition. The US Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names named an inlet after him on the north side of Thurston Island.

Randal (Ray) Murray Heke

Ministry of Works, Clerk of Works Ray Heke was part of the 1955-1958 Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition led by Sir Edmund Hillary. Heke was foreman for the construction party made up of men from the HMNZS Endeavour and the New Zealand Army, guiding the construction of New Zealand’s first Antarctic base, Scott Base, while Hillary and his team were off on their journey to the South Pole.

Originally from Waikanae, Heke, now 89 years old, was awarded the New Zealand Antarctic medal in June this year. Proud to have been one of the first Māori in the ice, of his Antarctic experience he said:

“I got on very well with Ed and he was a great leader and as leader of the construction team I got to know him very well down there. He was keeping an eye on progress and what I was doing and it was something I will always remember, being involved in his preparation to travel to the South Pole and my building the base from which he was to take off for his expedition.” Waateanews.com, September 5, 2017

Ramon (Ray) Tito

Able Seaman Ramon Tito was also part of the 1955-1958 Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition led by Sir Edmund Hillary, voyaging to Antarctica on the HMNZS Endeavour. Tito (also named Te Tou in some accounts) officially raised the New Zealand flag at the opening of Scott Base in 1956. Recalling the event nearly 50 years later, Tito said:

“At the time we were having a beard-growing contest and because I had less hair than Jim, I got the job to raise the flag. I did not think too much of it but when I got home from that trip, everyone would say, ‘There’s the guy who put the flag up.’ Then I started thinking, maybe I did do something.” Call of the Ice, p.29

Robert J. (Bob) Sopp

Diesel engineer and fitter mechanic from Kaingaroa Forest, Wairoa, Hawke’s Bay, Bob Sopp was selected as one of twelve wintering personnel for the tenth New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition, and as part of the 1966-1967 US Operation Deep Freeze. At only 21 years of age, Sopp had complete charge of the diesel generating plant supplying all power for the base.

Sopp carved a tekoteko (figurehead) which was presented by Scott Base to the CPO Mess at McMurdo Station. The carving was inscribed:“Rurea Taitea, kia Toitū, ko Taikaka” which means to strip away the sapwood and expose the heartwood. It also means to choose friends who are dependable and steadfast. The whakataukī (proverb) acknowledged especially the journey in cultural restoration and understanding, and reflected the working culture of those in Antarctica.

Ngahuia Mita in Antarctica, with Professor Christina Hulbe, Kelly Gragg and Michelle Ryan, Summer 2016/2017. Photo courtesy of Ngahuia Mita.

Ngahuia Mita

Ko Maungahaumi te maunga

Ko Waipaoa te awa

Ko Horouta te waka

Ko Te Aitanga-a-Mahaki te iwi

Ko Ngati Wahia te hapū

Ko Mahaki te tangata

No Tūranganui-ā-Kiwa ahau

Ko Ngahuia Mita tōku ingoa.

My name is Ngahuia and I come from Te Tairāwhiti (The East Coast of the North Island). In the summer of 2016/17 I had the honour of travelling to Antarctica alongside scientists including Professor Christina Hulbe, Kelly Gragg and Michelle Ryan under the Ross Ice Shelf Programme (funded by NZARI Aotearoa). The wider purpose of the research programme is to examine the Ross Ice Shelf and its response to climate change. My role was as an intern focusing on Māori and Polynesian voyages to Antarctica and thus the whakapapa connection that we as Māori and Polynesian descendants have to the continent. The findings of this research highlight the importance of the inclusion of Māori and Polynesian voices in Antarctic research. The work of Antarctic scientists is ground-breaking and critical in understanding our planets response to climate change, a change that ultimately effects Māori, coastal communities and all of us. Therefore I believe the inclusion of mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) can only enhance these approaches. I acknowledge those who made it possible for me to experience what our tīpuna (ancestors) would have hundreds of years ago and all of the Māori Antarctic scientists, kaimahi (workers) and explorers that have gone before me.

List of items on display

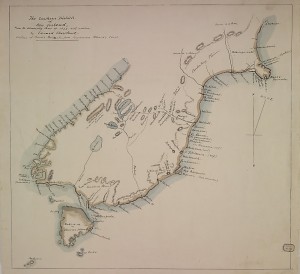

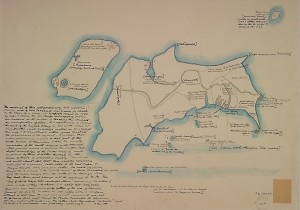

Map showing some recorded voyages of the Polynesians, page 3, in Best, E. 1923. Polynesian Voyagers: The Maori as a Deep-Sea Navigator, Explorer and Colonizer, Wellington, NZ: Government Printer. Hocken Published Collection.

Captain A. L. Nelson, commander of the Discovery II., welcoming Dr Potaka on embarking aboard the Discovery, en route to Little America, where he will take the place of Dr G. Shirey as medical officer to the Byrd Expedition. Evening Star, 15 February 1934, page 2, Hocken Newspapers Collection.

National Geographic Society (U.S.) Cartographic Division. Antarctica. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 1963. Hocken Maps Collection.

First day covers and envelopes bearing polar postmarks, H. P. Lowe Papers, Hocken Archives Collection, MS-2703/002

‘Antarctic’, New Zealand Antarctic Society quarterly news bulletin, New Zealand Alpine Club Records, Hocken Archives Collection, MS-3024/021

Photograph of Medical School Staff and Students, August 1930, University of Otago Medical School, Alumnus Association Inc. Records, MS-1537/708

List of stores loaded on the “Bear of Oakland”, 1934, Tapley Swift Shipping Agencies Limited Records, Hocken Archives Collection, MS-3165/016

‘Medical locker’ supplies list and Inward Manifest list of crew from the SS Jacob Ruppert, 1934, from Crew lists, invoices and bills of lading, H.L. Tapley and Company Limited: Papers relating to the Admiral

Byrd Expedition to the Antarctic, Hocken Archives Collection, MS-1138/003

Scrapbook relating to Byrd’s second expedition, Byrd Expedition Records, Hocken Archives Collection, AG-372/002

Photograph of Dr. Potaka uses “painless dentistry” on Corey, facing page 232, in Byrd, R. E. 1936. Antarctic Discovery. London: Putnam. Hocken Published Collection.

Photograph of PO Ramon Tito (second from left) with Sir Edmund Hillary, Sir Vivian Fuchs and PO Terry Devlin on HMNZS Endeavour, January 1958, Plate 1, in Harrowfield, D. L. 2007. Call of the ice: fifty years of New Zealand in Antarctica. Auckland, N.Z.: David Bateman. Hocken Published Collection.

Ngahuia Mita in Antarctica, with Professor Christina Hulbe, Kelly Gragg and Michelle Ryan, Summer 2016/2017. Photos courtesy of Ngahuia Mita.