Post prepared by Dr Ali Clarke, Library Assistant (Reference)

This year the University of Otago Department of Botany is celebrating its 90th anniversary. In honour of the occasion, I’ve been looking back at the beginnings of botany, as revealed in the university’s archives here at the Hocken. Although the “department” is generally dated from 1924, when John Holloway began as lecturer, botany was taught as early as the 1870s. In the university’s early decades, when student numbers were small, there were very few teaching staff and they had a wide brief. The first professor of “natural science” – F.W. Hutton – taught geology as well as biology. The 1877 University Calendar offered a general introductory course called “Principles of Biology,” as well as papers in zoology and botany. This pattern was to continue for several decades. The 1877 botany course covered “the structure, functions, and distributions of the orders of cryptograms, and the principal orders of phanerogams,” as well as “the use of the microscope.”

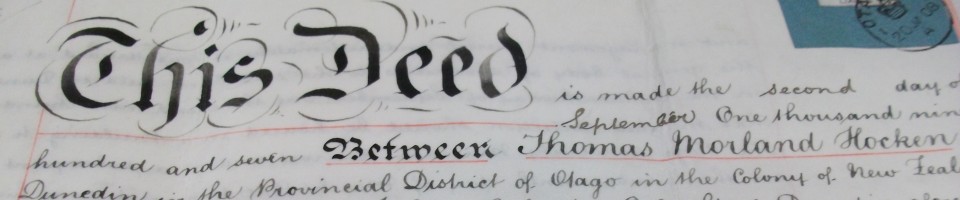

Geology and biology were separated into two positions after Hutton left in 1880. Thomas Parker held the chair in biology from 1880 to 1897 and William Benham from 1898 to 1937. Both were brilliant scientists, but their chief research interests were in zoology rather than botany. As the university grew, the workload of teaching all aspects of biology to science, medical, dental and home science students became increasingly burdensome. Professor Benham managed to get an assistant – Winifred Farnie – to help with biology teaching from 1916 to 1918. In 1918 he suggested that it was time for the university to appoint a lecturer in botany, but the Council decided to delay for a year. The 1919 calendar notes that instruction in botany “is not provided at present” – presumably Benham had decided he was over-stretched and could no longer offer the course. He repeated his request for a botany lecturer to the council that year, and this time approval was granted. Benham already had somebody in mind for the post – his former student Winifred Betts.

Rather than simply appointing Betts, the council decided to advertise the post of botany lecturer. Were they, perhaps, reluctant to appoint a woman? As it turned out, they received three applications, all from women, and selected Betts as Otago’s first botany lecturer. For Benham, this was a long overdue development. In 1919, writing in honour of the university’s jubilee, he commented: “It is a curious fact that in each of the four colleges in New Zealand it has been expected that one man shall undertake to teach efficiently those two subjects [zoology and botany], which in England, even in fourth-rate educational institutions, have for many years been entrusted to two distinct individuals.” He was happy to report that Otago had now “set the example to the other University Colleges by appointing a lecturer in botany”.

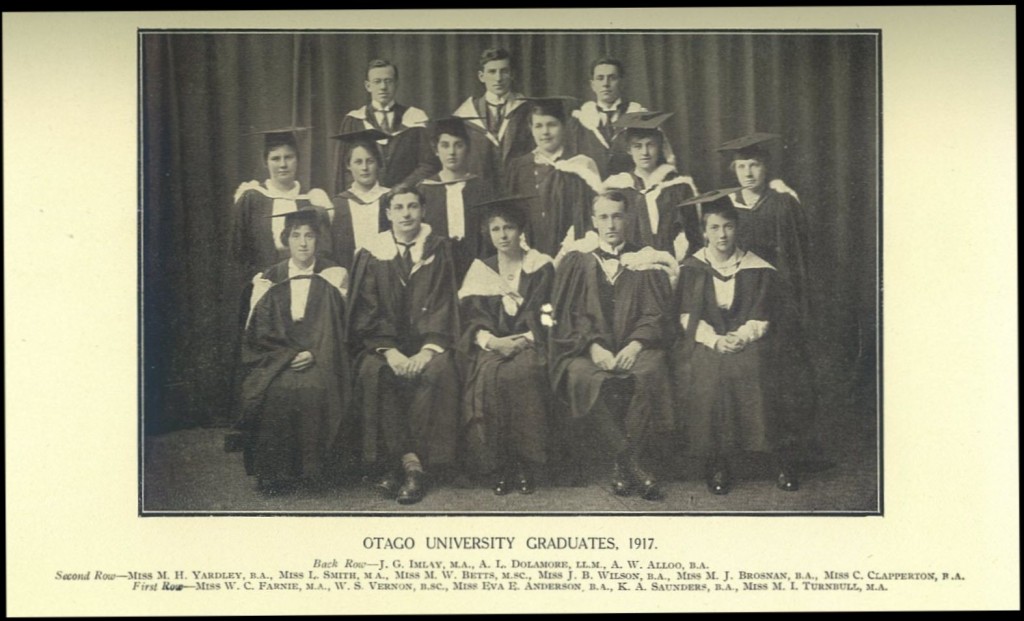

Winnie Betts was just 25 years old when she commenced her new position at the beginning of 1920. Born in Moteuka, she was educated at Nelson College for Girls, receiving a University National Scholarship in 1911. She then came to Otago, graduating BSc in 1916 and MSc in 1917. She was clearly one of the more capable students of her era, and by 1915 Benham had selected her as a demonstrator in biology. On completing her MSc she received a National Research Scholarship – one was awarded at each university each year. This provided her with an income of £100 a year along with lab expenses so she could carry out independent research. In 1919, at a lecture to an admittedly partisan audience in Nelson, distinguished botanist Leonard Cockayne described Betts as “the most brilliant woman scientist in New Zealand.”

In December 1920 Winnie Betts married another brilliant Otago graduate, the mathematician Alexander Aitken. Aitken, whose studies were interrupted by war service (he was badly wounded at the Somme), was by then teaching at Otago Boys’ High School. This was an era when most women left paid employment when they married, so it is intriguing that Winnie Aitken continued working as botany lecturer for some years. She joined a handful of women on Otago’s academic staff. As well as the women of the School of Home Science, there were Isabel Turnbull in Latin, Gladys Cameron in Bacteriology and Public Health and Bertha Clement in English; others came and went during Winnie’s years at Otago.

Winnie Aitken’s career as botany lecturer came to an end in December 1923. Her husband had been awarded a scholarship for postgraduate study and they moved to Edinburgh, where he had a long and distinguished academic career as a mathematician. Alexander died in 1967 and Winnie in 1971; they had two children. Various women have since taught botany at the University of Otago; indeed, it has been one of the more gender-balanced of the academic departments. As the department celebrates its 90th anniversary with Prof Kath Dickinson at its head, it seems an appropriate moment to remember the woman who pioneered it all!