Post prepared by Kari Wilson-Allan, Hocken Collections Assistant, Researcher Services

Today being International Women’s Day, it seems fitting to delve into the history of some Dunedin women – our own real housewives.

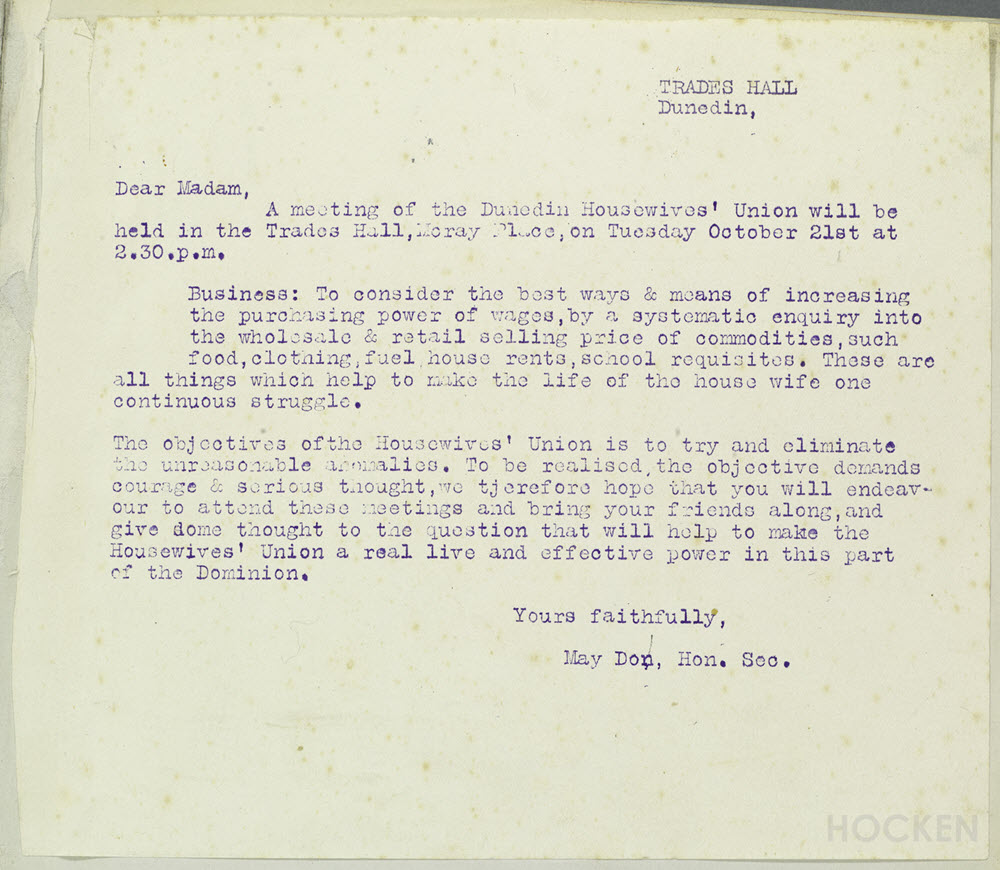

Established in late 1930, in the midst of the Great Depression, the Dunedin Housewives’ Union, headed up by the dynamo Mrs Alice Herbert, aimed to become a ‘real live and effective power in this part of the Dominion’. Meetings were held fortnightly, initially in the Dunedin Trades Hall, with a 2/6 annual membership fee.

First page, Minute Book (1930 – 1941) AG-002-01

Subjects under discussion revolved around, among other things, the quality and cost of foodstuffs, fuel, schoolbooks, and housing. Meat was ‘the foundation of the usual daily dinner’ and therefore ‘of utmost importance to the housewife’. That available in Dunedin was the ‘dearest in the Dominion’. Milk and bread also drew attention; calls for the pasteurisation of milk and the packaging of bread appeared in local newspapers, along with requests for a municipal milk supply as a means to cut distribution costs.

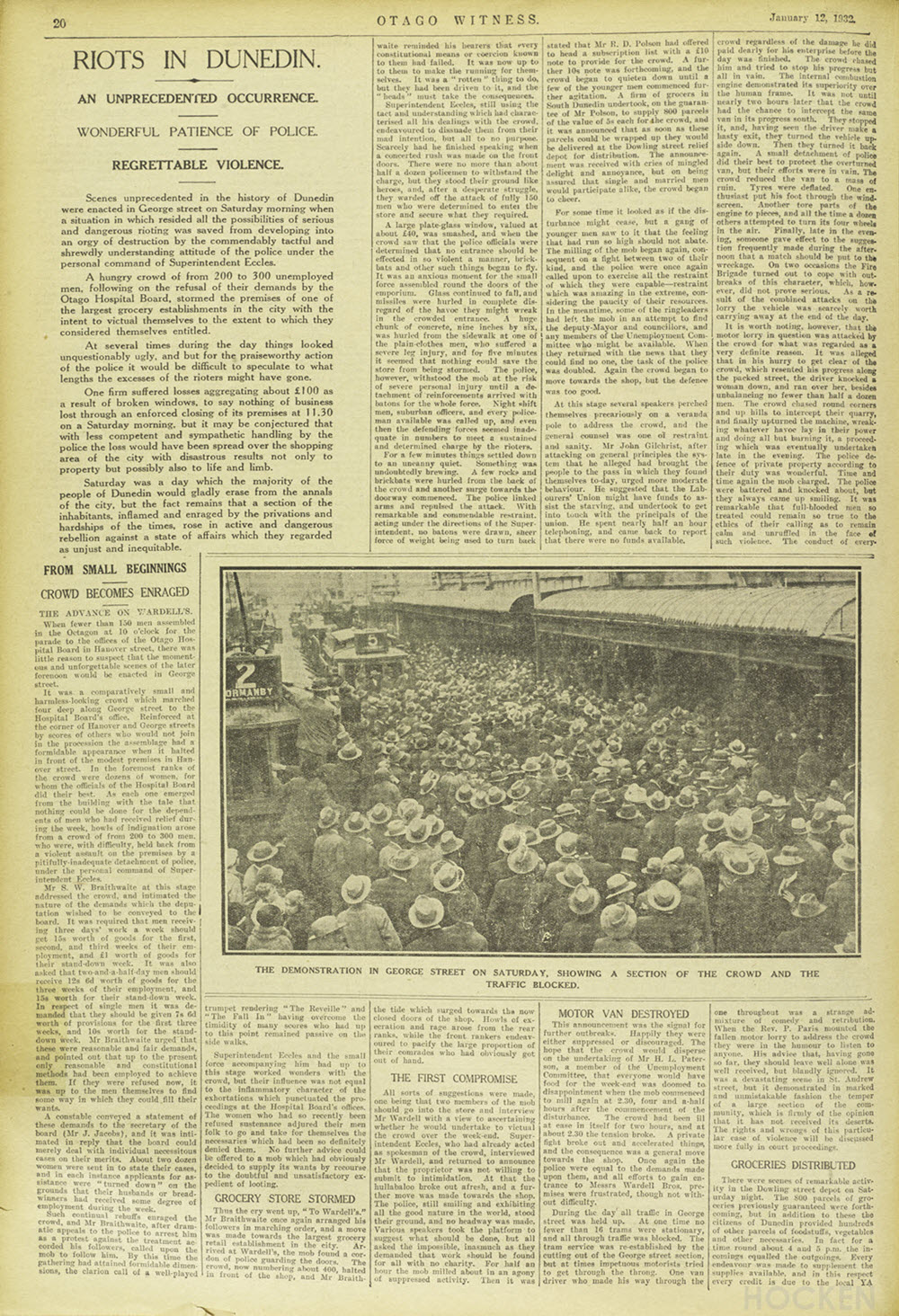

Media coverage of riots in Dunedin, Otago Witness, 12 January 1932, p.20.

Fundraising events were common features in the women’s calendars. They organised bazaars, jumble sales, hat-trimming competitions, guess-the-weight-of-the-ham competitions (ham kindly supplied by Wolfenden and Russell), even baby shows. A ‘hot pea and hot dog stall’ in 1931 was the cause of ‘much meriment [sic] ’.

As well as supporting the community with events like the 1933 party for the old-age pensioners at Talboys’ Home (lollies donated by Wardell’s Grocery), which was intended to ‘bring a little brightness into their drab lives’, the women looked after their own. One member was gifted cocoa as she was ‘in great need of additional nourishment’.

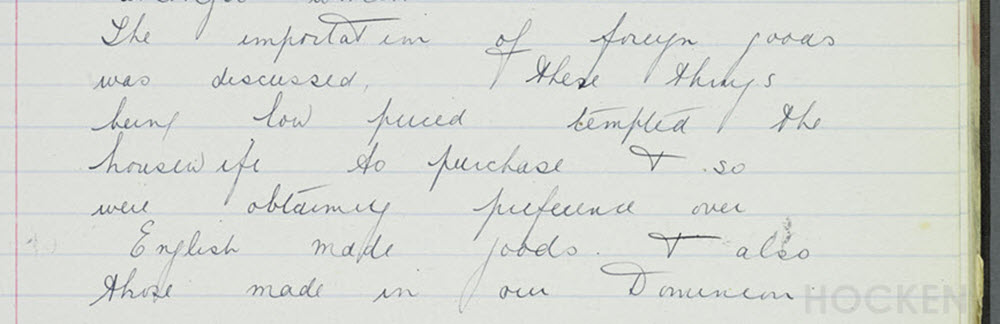

The employment and unemployment of women concerned the Union. It was recognised that often young women would be hired for a short period of time and then dismissed, leading to insecurity. Compounding the problem was the higher costs of living in the South Island, where food and clothing were dearer. The importation of foreign goods also raised their ire.

Temptations to housewives, Minute Book (1930 – 1941) AG-002-01, p.144

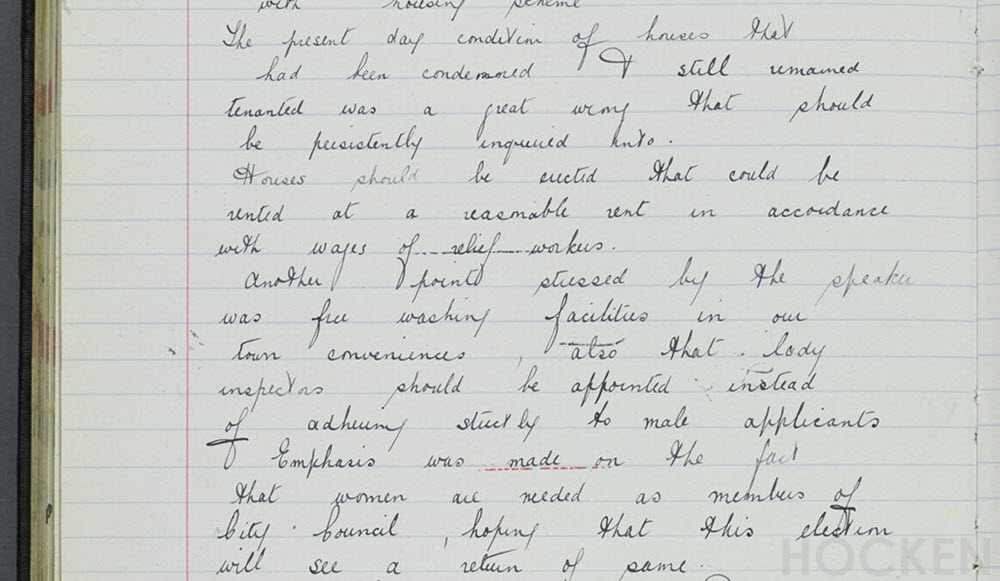

Housing conditions were decried; condemned buildings were at times tenanted. Washing facilities were in short supply, women needed to be recruited as inspectors, and to have a larger role in the City Council over all.

Housewives’ concerns, Minute Book (1930 – 1941) AG-002-01, p.125

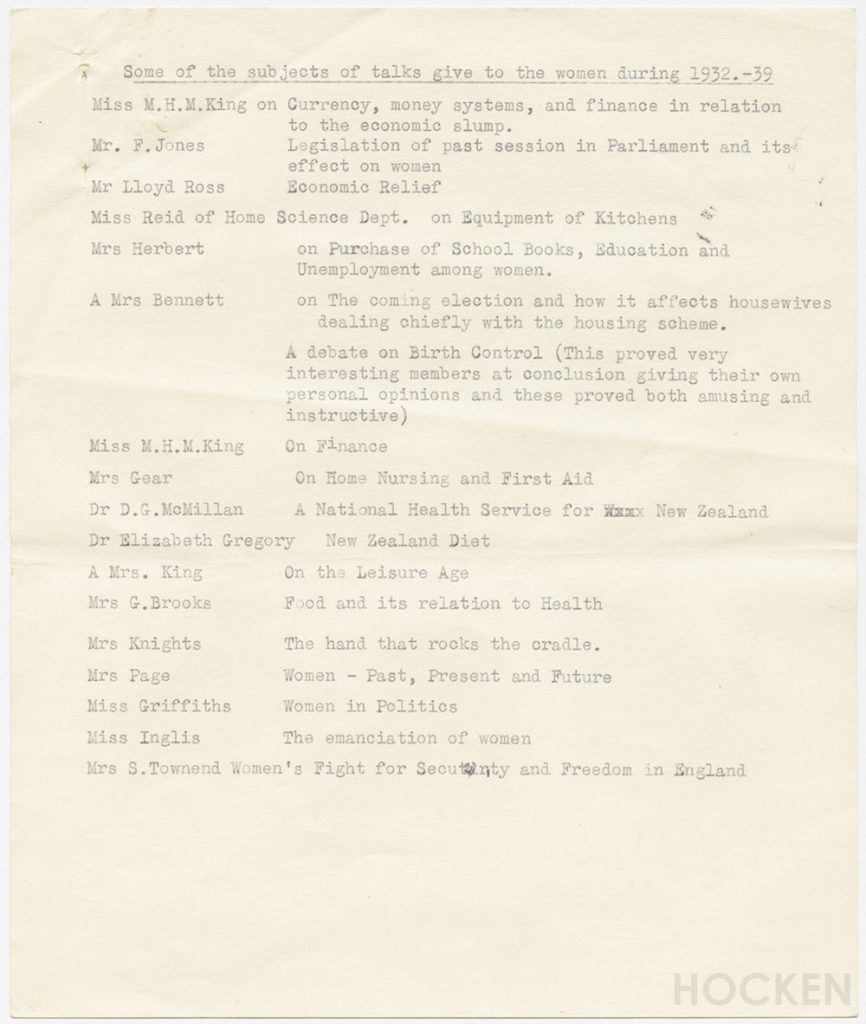

Meetings often featured speakers or debates. One such debate in 1933 on the subject of birth control proved to be ‘very interesting’, and at its conclusion, members shared their personal opinions, which were both ‘amusing and instructive’.

A selection of speakers’ subjects in the Union’s first decade, Notes on the history of the Association, AG-002-13

Who were the women of the Union? This is not an easy question to answer. Members of the Executive of the first year included a Mrs. Seddon, a Mrs. Anderson and a Mrs. Allen. Without their first initials, finding the correct woman in electoral rolls has proved to be a minefield. Sometimes the addition of a husband’s initial was a vital clue.

The members certainly had adequate time to contribute to their cause, to pay their annual dues and rent their premises. Based on this and a number of other clues, I surmise that they were certainly not the poorest of the poor at that time. They had education behind them, and political contacts.

Alice Herbert’s husband was the Secretary for the Dunedin Drivers’ and Storemens’ Union, and he, along with Alice, was heavily involved in the Labour Party. In 1934, Alice tendered her resignation for the president’s role, based on her other commitments, but this was refused pending a determination of how time-consuming her other political activities would prove to be. That the Union did not accept her resignation seems a signifier of her great influence and energy.

Women around New Zealand came to hear of the Dunedin Union, and made contact, wanting to establish similar groups of their own. Unions formed in Invercargill, Waimate and Napier and elsewhere, eventually growing a network around the country. Affiliations with the National Council of Women developed, and by the 1950s, the name Union was dropped for the less combative sounding Association.

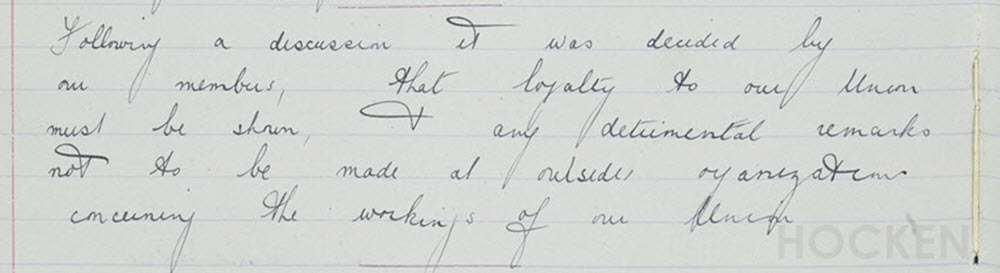

It would be unfair of me to allude to ‘real housewives’ without supplying some element of drama. The minutes do indicate certain conflicts of interest, perceived insults and tempestuous resignations, but to focus on these would belittle the valuable contributions made to the community. Certainly as membership grew, challenges arose. Rules were established, and prospective members needed to be introduced by current members to be admitted. By June 1934 there was concern that ‘misrepresentation’ could arise as a consequence of ‘business [of the Union] being discussed outside the organization’, and in October of that year it was declared that ‘loyalty to our union must be shown.’

Minute Book (1930 – 1941) AG-002-01, p.164

Curiosity piqued by this first minute book? Come in and explore them further. The minute books stretch from 1930 through to 1974, are unrestricted, and contain myriad avenues for investigation.