Practising History (HIST 353) student Sam Bocock wrote this blog in response to reading an Otago Preventive Medicine dissertation. An invaluable primary source of New Zealand medical and social history, the Preventive Medicine dissertation collection comprises more than three thousand public health projects written by fifth-year medical students from the 1920s to the late 1970s. Topics range from studies on current health issues, such as asthma, to health surveys of various occupational groups and of New Zealand towns and Maori. Permission is required to access the dissertations. An index to the dissertations is available.

Soothing Springs or Putrid Pools?

Imagine a bone rattling, teeth chattering, miserable winter afternoon. Chicken soup may be for the soul, but a natural hot pool warms the mind, body and spirit. Welcome to Rotorua – a thermal wonderland. The central North Island settlement offers a cornucopia of natural hot water springs and pools. These have and continue to draw visitors from across the world since the 19th century, simply to relax.

Scene at the Blue Baths in Rotorua, circa 1935, showing the pool, and three women in bathing suits. Photographer unidentified.[1]

I suggest that geothermal tourism had national significance, interest, and influenced this study in a number of ways. Rotorua was, and is, a huge contributor to the growth of tourism in New Zealand. However, the baths were not always the focus. The Pink and White Terraces were world renowned in the nineteenth century. Tourists flocked to view this ‘eighth wonder of the world’.[2] On the 10th of June 1886, Mount Tarawera Volcano erupted and obliterated the terraces, greatly modified the nearby hydrothermal features, and destroyed tourism facilities.[3] After the volcanic destruction of the terraces, the focus of geothermal tourism shifted to Rotorua township.[4] For most of the last century Rotorua had been New Zealand’s main tourism centre and for the first half of that period the principal attraction was geothermal activity, especially bathing in mineral water, either for pleasure or for medicinal purposes.[5]

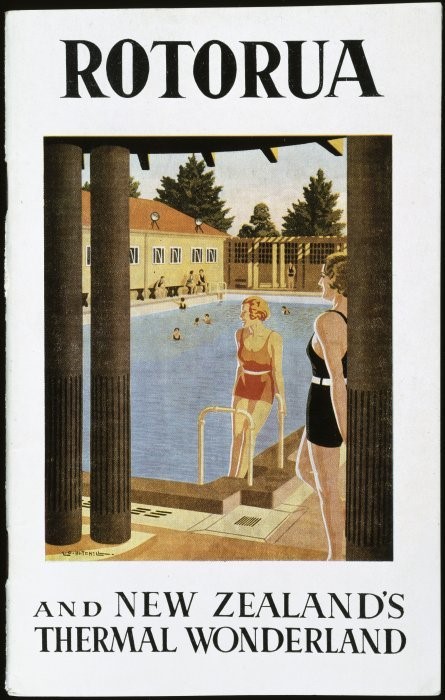

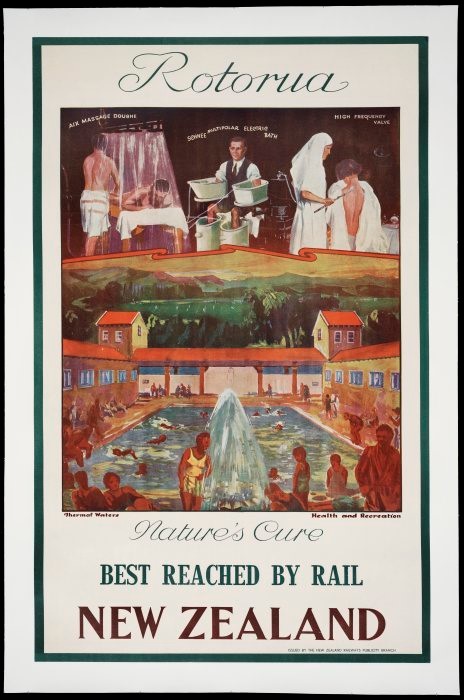

The government’s investment in the development of the Rotorua township, associated sanatorium and spas led to the establishment of the world’s first government tourism department in 1901.[6] The Department of Tourist and Health Resorts marketed geothermal tourism,[7] as seen below in the booklets and brochures.

An example of the Department of Tourist and Publicity’s attractive brochures of the 1930s.[8]

A montage of illustrations of activities and facilities available at Rotorua in New Zealand Railways Magazine.[9]

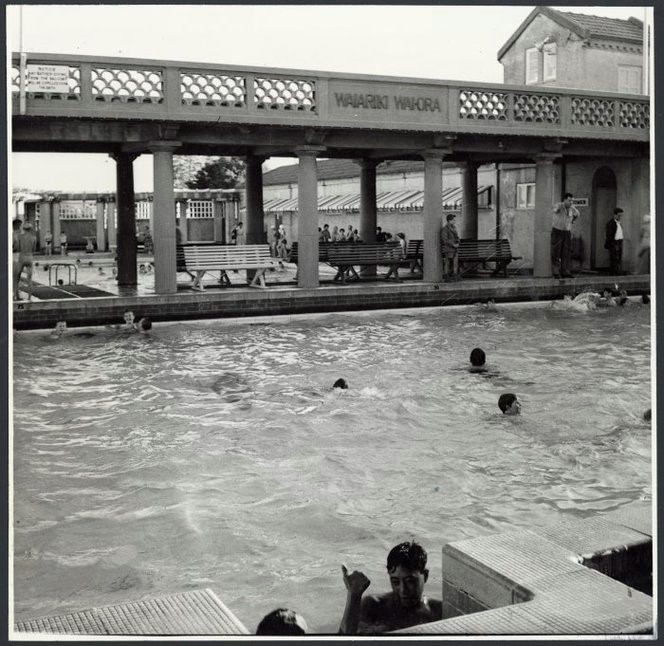

They found that the water supply was clean, the real problem was human pollution. The bulk of the water came from an actively boiling spring proven to be bacteriologically sterile.[12] During the busy summer season, 800-1000 persons used the baths daily. After a few hours of exposure to human pollution (hair, skin, mucus, open wounds, etc) and excellent temperatures for bacterial growth, outgoing water showed an alarmingly high bacterial count.[13] This could lead to eye, ear and respiratory passage infections.[14]

The methods of purification in Rotorua were out of date and sub-standard. The most pernicious mistake was the belief that the frequent changing of the water would maintain healthy standards.[15] No effort was made to maintain pure water apart from emptying and cleaning every 48 hours, which was insufficient in the face of counts such as 25,000 organisms per cubic centimetre.[16] The students recommended that a continuous purification system and chloramine treatment be implemented. To keep the water sterile and avoid irritation chlorine content had to be between 0.3-0.5 parts per million.[17] Observations in the past indicated that below 0.3 bacteria are not killed sufficiently quickly, and above 0.5 eye irritation was marked.[18]

Photo gives some indication of their popularity for recreation at that time, and the layout of the facilities in relation to the hygienic problems. Photographer unknown, circa 1959.[19]

Certain disadvantages made the choice of purification system difficult. The sulphur dioxide present was a powerful dechlorinating agent, and acted as a reducing agent on chlorine, complicating treatment processes.[23] The acid and mineral content caused corrosion of all metal pipes except lead, and siliceous deposits on pipes and other apparatus created constant trouble for engineers.[24] Advantages the baths offered included free water that did not require heating, and (arguably) enough of it for practical needs.[25]

Although it is a preventative medicine dissertation, this study highlighted resource exploitation can be linked to the increase of tourism. In the 1930s, residents of Rotorua began using geothermal wells to heat residential, commercial, and government buildings. Over the decades, increasing demand on the geothermal resource resulted in the failure of a number of hot springs.[26] Originally there were 63 boiling features at Whakarewarewa, but, by 1985, only 38 were still boiling, and only 4 of 16 geysers erupted on a daily basis.[27] I am suggesting that government investment in Rotorua and the opening of the Blue Baths in the 1930s were catalysts for future thermal resource exploitation. In 1986 the New Zealand government ordered the closure of about 40% of the geothermal wells in Rotorua City.[28] There is an obvious link between the growth of tourism, and the depletion of natural resources.

Carl Leonard, a guide at Whakarewarewa, poses at the site of the extinct Papakura Geyser, 1986. Photographed by Merv Griffiths.[29]

[1] Blue Baths at Rotorua, ca 1935, National Library of New Zealand Website, https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22656675.

[2] Shirley Barnett, “Maori tourism,” Tourism management 18, no. 7 (1997): 471.

[3] Kenneth A. Barrick, “Geyser decline and extinction in New Zealand- energy development impacts and implications for environmental management,” Environmental Management 39, no. 6 (2007): 790.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ian Rockel, Taking the waters: early spas in New Zealand (Government Printers, 1986), 20.

[6] Melissa Climo, Sarah D. Milicich, and Brian White, “A history of geothermal direct use development in the Taupo Volcanic Zone, New Zealand,” Geothermics 59 (2016): 218.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Mitchell Leonard Cornwall, Rotorua and New Zealand’s thermal wonderland, ca 1930-1937, National Library of New Zealand Website, https://natlib.govt.nz/records/23063926.

[9] New Zealand Railways Publicity Branch, “Rotorua, nature’s cure. Thermal waters, health and recreation. Best reached by rail, New Zealand,” issued by the New Zealand Railways Publicity Branch, ca 1932, National Library of New Zealand Website, https://natlib.govt.nz/records/23179795.

[10] J.R. Hinds and S.E. Williams, ‘A public health survey of the swimming baths of Rotorua’, 1938, 1.

[11] D.M. Stafford, The founding years in Rotorua: A history of Events to 1900 (Rotorua District Council, 1986), 448.

[12] Hinds and Williams, 87.

[13]Ibid, 88.

[14] Ibid, 94.

[15] “Below Standard,” Auckland Star, 13 August 1938.

[16] Hinds and Williams, 108.

[17] Ibid, 109.

[18], J.A. Braxton Hicks, R. J. V. Pulvertaft, and F. R. Chopping, “Observations On The Examination Of Swimming-Bath Water,” British medical journal 2, no. 3795 (1933): 603.

[19] The Blue Baths, thermal baths in Rotorua, ca 1959, National Library of New Zealand Website, https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22779571.

[20] Hinds and Williams, 110.

[21] Ibid, 111.

[22] Ibid, 112.

[23] Ibid, 107.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Kenneth A. Barrick, “Environmental review of geyser basins: resources, scarcity, threats, and benefits,” Environmental Reviews 18, no. NA (2010): 222.

[27] Ministry of Energy, The Rotorua Geothermal Field — A report of the Rotorua geothermal monitoring programme and task force 1982–1985, Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, 1986, 48.

[28] Barrick, “Environmental review of geyser basins: resources, scarcity, threats, and benefits,” 222.

[29] Carl Leonard, a guide at Whakarewarewa, at the site of the extinct Papakura Geyser – Photograph taken by Merv Griffiths, Dominion post, National Library of New Zealand Website, https://natlib.govt.nz/records/23173714.

Bibliography

Barnett, Shirley. “Maori Tourism.” Tourism Management 18, no. 7 (1997): 471-73.

Barrick, Kenneth A. “Environmental Review of Geyser Basins: Resources, Scarcity, Threats, and Benefits.” Environmental Reviews 18 (2010): 209-38.

Barrick, Kenneth A. “Geyser Decline and Extinction in New Zealand—Energy Development Impacts and Implications for Environmental Management.” Environmental Management 39, no. 6 (2007): 783-805.

“Below Standard.” Auckland Star. 13 August 1938.

Blue Baths at Rotorua. Ca 1935. National Library of New Zealand Website, https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22656675.

Climo, Melissa, Sarah D. Milicich, and Brian White. “A History of Geothermal Direct Use Development in the Taupo Volcanic Zone, New Zealand.” Geothermics 59 (2016): 215-24.

Cornwall, Mitchell Leonard. Rotorua and New Zealand’s thermal wonderland. Ca 1930-1937. National Library of New Zealand Website, https://natlib.govt.nz/records/23063926.

Hicks, JA Braxton, R. J. V. Pulvertaft, and F. R. Chopping. “Observations On The Examination Of Swimming-Bath Water.” British medical journal 2, no. 3795 (1933): 603-606.

Hinds, J.R. and S.E. Williams. ‘A public health survey of the swimming baths of Rotorua’, 1938.

Leonard, Carl. A guide at Whakarewarewa, at the site of the extinct Papakura Geyser. Photograph taken by Merv Griffiths. Dominion post. National Library of New Zealand Website, https://natlib.govt.nz/records/23173714.

Ministry of Energy. The Rotorua Geothermal Field — a report of the Rotorua geothermal monitoring programme and task force 1982–1985. Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, 1986.

New Zealand Railways Publicity Branch. “Rotorua, nature’s cure. Thermal waters, health and recreation. Best reached by rail, New Zealand.” Issued by the New Zealand Railways Publicity Branch. Ca 1932. National Library of New Zealand Website, https://natlib.govt.nz/records/23179795.

Rockel, Ian. Taking the Waters. Government Printing Office Publishing, 1986.

Stafford, D. M. The Founding Years in Rotorua: A History of Events to 1900. Ray Richards, 1986.

The Blue Baths, thermal baths in Rotorua. Ca 1959. National Library of New Zealand Website, https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22779571.