Post researched and written by Dr Anna Petersen, Assistant Curator of Photographs.

Housed in the Hocken Photographs Collection is an album compiled by a World War I soldier, Francis Leddingham McFarlane (1888-1948) from Dunedin, who occupied a short-lived but significant place in the long history of the Shellal Mosaic.

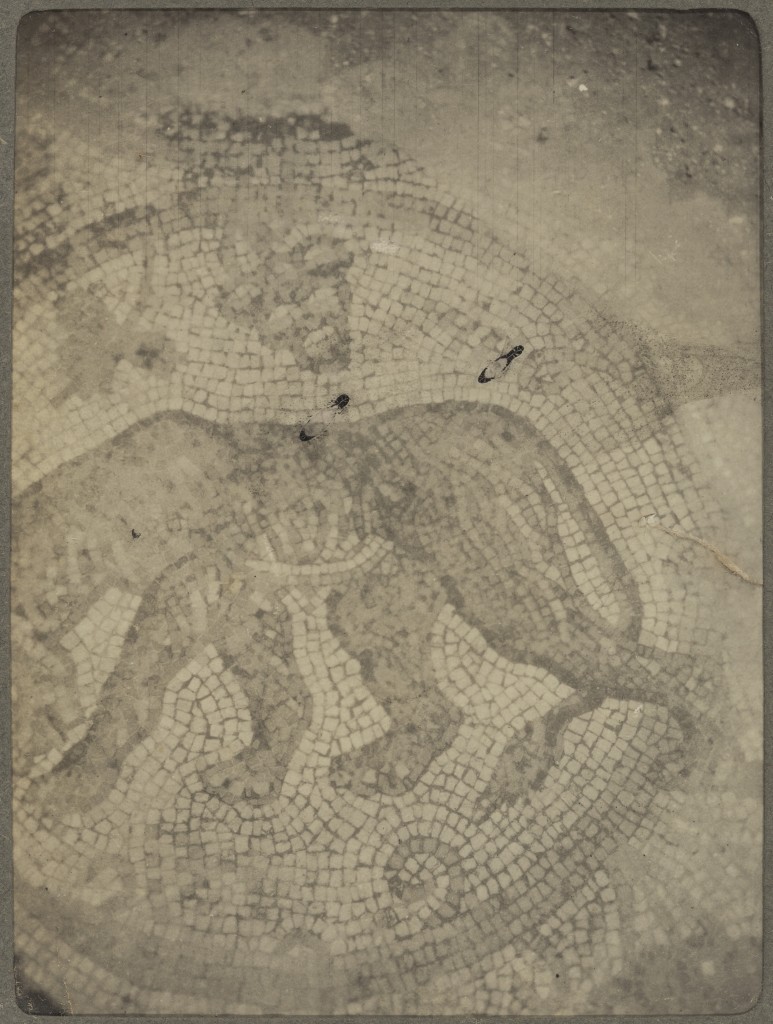

Sapper McFarlane of the New Zealand Wireless Troop was serving in Palestine in April 1917, when fellow ANZAC soldiers near Shellal stumbled across pieces of this sixth century mosaic. The chance discovery was made during the second battle of Gaza on the floor of a captured Turkish machine gun outpost, located on a small hill overlooking the cross roads of what would once have been the main road between Egypt and Jerusalem.[i]

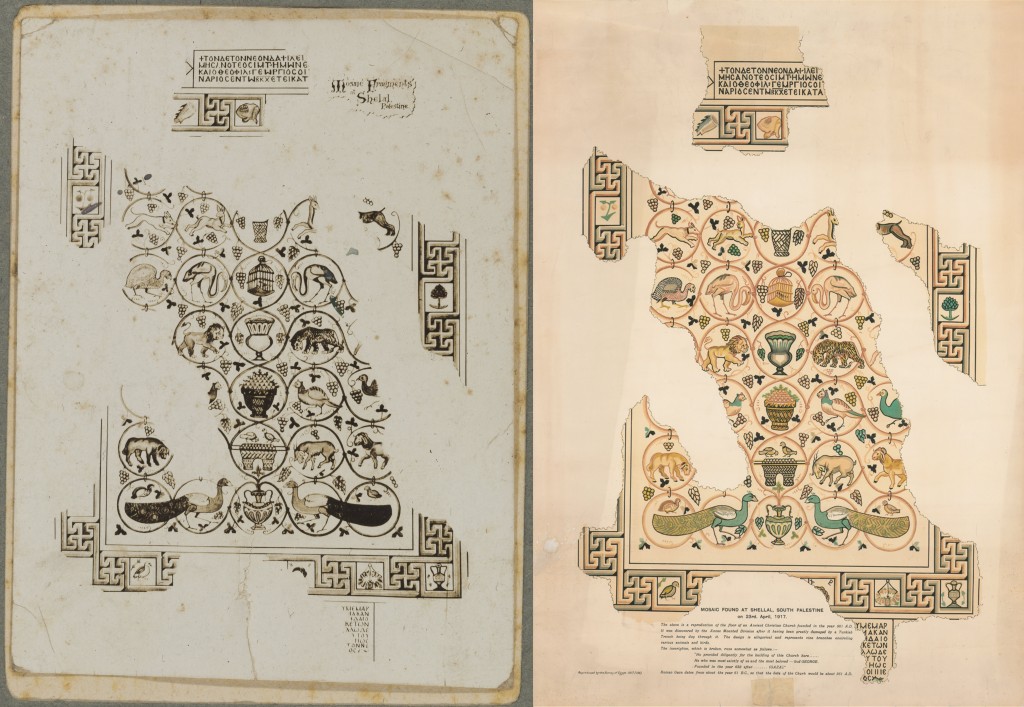

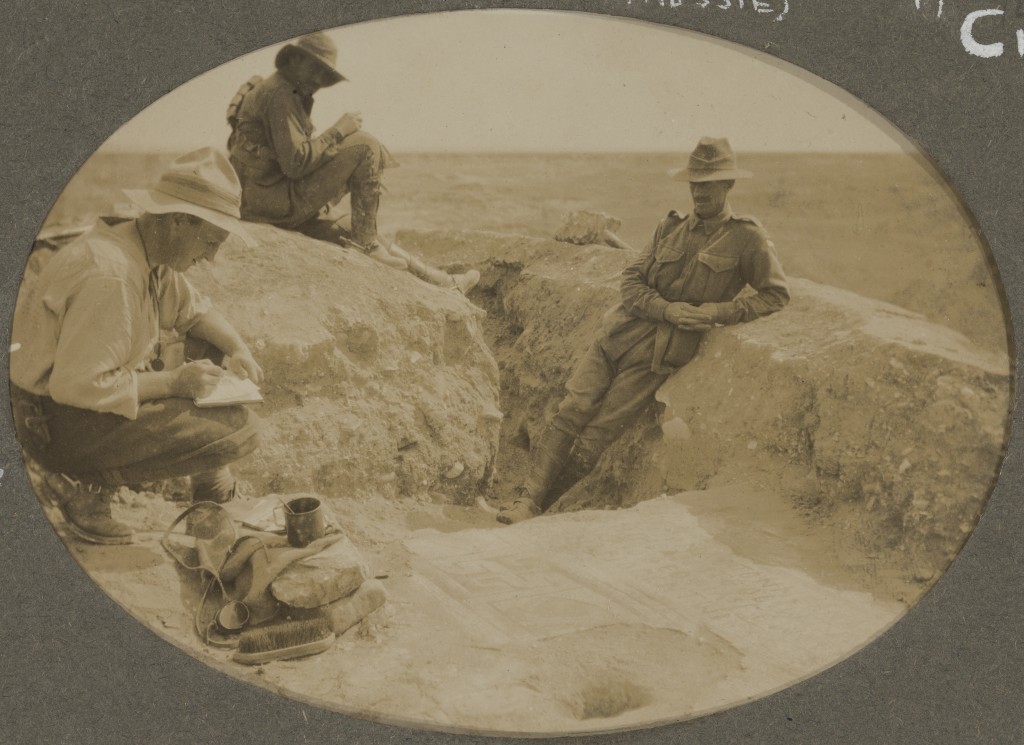

The soldiers reported their find to Senior Chaplain, Rev. W. Maitland Woods, who had a keen interest in archaeology and made a habit of entertaining the troops with stories about the Holy Lands where they were based.[ii] Rev. Maitland sought professional advice from curators at the Cairo Museum and gained permission to organise a group of volunteers to uncover and remove the remains.[iii] Sapper McFarlane was given the job of drawing what they uncovered (fig. 1).[iv]

Album 213 includes three photographs showing sections of the Shellal Mosaic in situ (figs 2, 3 and 4), as well as a photograph of the sketcher at work and his completed drawing of the whole carpet-style design (fig. 5).

A colour lithograph of McFarlane’s drawing was subsequently published in Cairo but, like the photograph, does not do full justice to the subtle hues. An example of the lithograph can also be found at the Hocken, housed in the Ephemera Collection (fig.6).

Figure 5. Photograph of drawing of mosaic fragments. P1993-024-011a. Figure 6. Lithograph of mosaic found at Shellal, South Palestine on 23rd April 1917. Hocken Posters collection acc no. 816608.

The full significance of Sapper McFarlane’s drawing is explained in a booklet, written by A.D. Trendall and published by the Australian War Memorial Museum in 1942, some decades after the mosaic was handed over to the Australian government in 1918. Trendall relates how a second drawing, made by Captain M.S. Briggs six weeks later, reveals that during the interim, portions of the mosaic went missing. Other soldiers probably took away pieces of the peacock and border in the lower right corner in particular as souvenirs and these proved impossible to recover. Fortunately 8,000 tesserae survived from the top inscription written in Greek; enough to learn that the mosaic once decorated a church dating to A.D.561-2 and honoured a bishop and a priest called George. Anyone wanting to learn the whole story plus an analysis of the imagery, technique and style, can read Trentham’s booklet, a later edition of which is housed with the album at the Hocken.

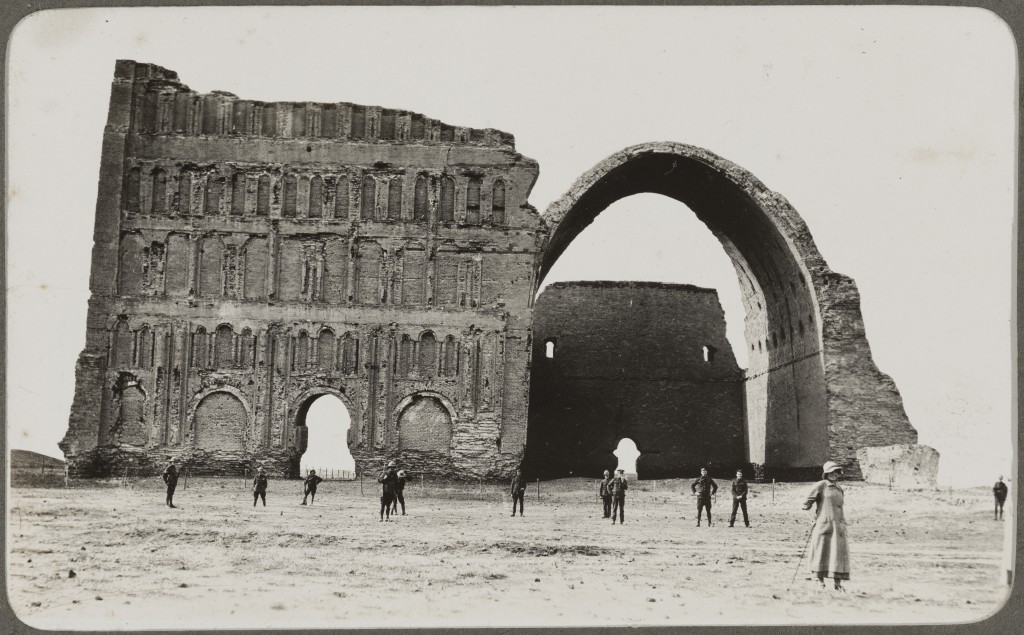

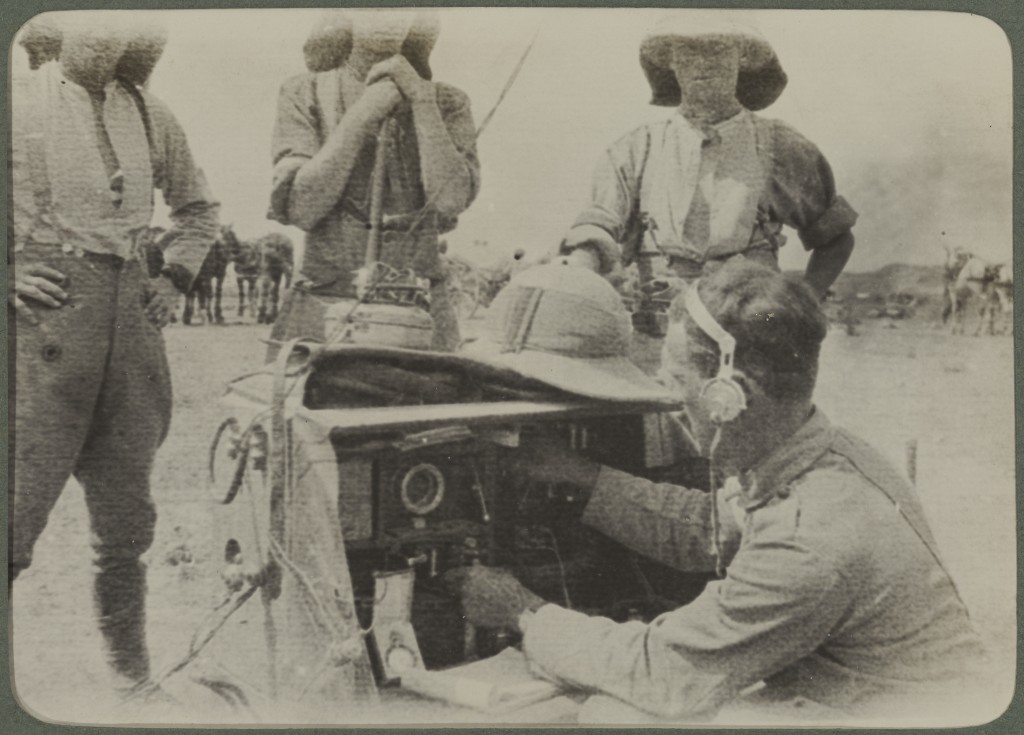

Frank McFarlane went on to serve as a war artist in the Middle East and continued to paint and draw after returning to civilian life. Other photographs in album 213 (all now available online via Hakena) help document McFarlane’s time during World War I in Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq). These include a view of the Arch of Ctesiphon near Baghdad (fig. 7) and a soldier operating a pack set wireless in the field (fig. 8). A sketchbook in the Hocken Pictorial Collections dates to the 1930s when McFarlane worked as a postmaster at Lawrence in Central Otago. It includes pencil portraits of local people in Lawrence and remnants of the gold-mining days.

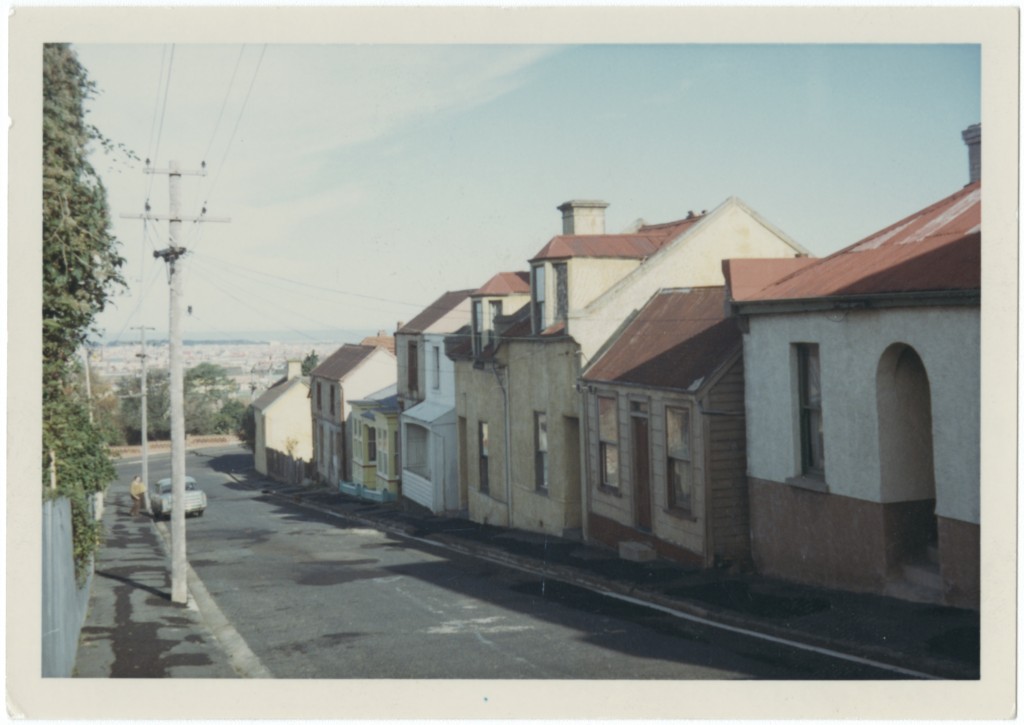

Frank McFarlane married Bessie King and together they had two daughters who became professional painters with work also represented at the Hocken that reflects a shared interest in vestiges of the past. Their paintings are not currently available online for copyright reasons but Heather McFarlane (1925-2011) married New Zealand diplomat, Sir Laurie Francis and a loose photograph in the back of album 213 shows her viewing the Shellal Mosaic on display at the Australian War Memorial Museum in 1965. A drawing by Shona McFarlane-Highett (1929-2001) entitled ‘Dunedin-Palmyra’ (1965) depicts a quarter of the city that was once inhabited by Lebanese. A photograph in the Dunedin Public Library Collection at the Hocken (P1990-015/49-264) shows a similar row of houses, presumably named after the Syrian city of Palmyra and since demolished.

These days the Shellal Mosaic is internationally recognised as one of the finest sixth-century mosaics in existence and as we prepare to welcome more Syrian refugees to the city, it may be a comfort for them to know that the Hocken also preserves some memories and material of relevance to that part of the world.

[i] A.D. Trendall, The Shellel Mosaic and Other Classical Antiquities in the Australian War Memorial Canberra, Canberra, 1964, p.9.

[ii] General Sir Harry Chauvel, ‘Foreword’ in The Shellel Mosaic and Other Classical Antiquities in the Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1964.

[iii] Trendall, p.9.

[iv] Ibid.

Hi Anna,I just came across this very interesting blog. Most of the photos I have not seen before. Frank was my great uncle and I have been looking for new information about him. I have some of his sketches.

Thank you.

Hi William, So glad you found it interesting 🙂 What are your sketches of?

Paintings of Border posts between Egypt and Palestine, Orange seller at Lake Timsam and Some burial shrines.