Post prepared by Kari Wilson-Allan, Library Assistant (Reference)

To open a volume of The Otago Police Gazette is to enter into a colourful world that warrants investigation. What follows is a series of observations based on issues from the early and mid-1870s.

The Gazette served as a key communication tool for the police force between stations and regions. Without photography or modern electronic communications, police work would have been very different in the late nineteenth century to how it is today. Nonetheless, their reliance on the circulation of written material is part of what makes for such a fascinating document now.

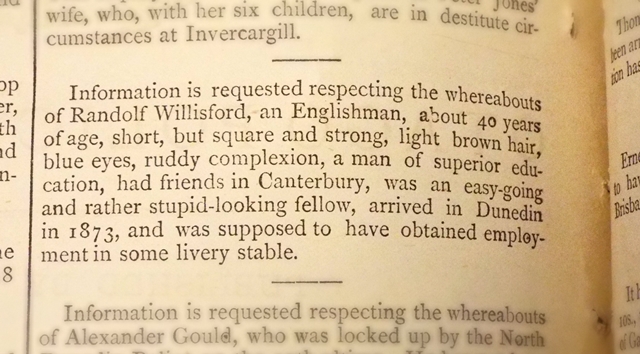

The mug shot was not yet employed as a means of recording appearance. Consequently, vivid textual description is used, often offering more information than what a photograph could ever provide. For instance, a group of wanted felons were described variously in the 30 November 1872 issue: Thomas Sheehan had a “dirty sulky appearance, [and] speaks with a broad Irish accent;” William Walsh “always keeps his mouth open;” James Cummins was of a “coarse Yankee appearance,” and Thomas Howe had “thin features, Roman nose, smart appearance, [and was] fond of horse-racing.”

Edward Chaplin was described in the 30 September 1871 issue as “a clerk and mining agent, below the middle height, broad shoulders, stooped and awkward gait, fresh complexion, grey hair, grey prominent eyes – occasionally bloodshot – very short sighted, Jewish appearance; he usually keeps his hands in his trousers pockets and looks on the ground when walking; he was dressed in a black sac coat, dark grey overcoat, dark striped trousers, and black silk hat; addicted to drink.”

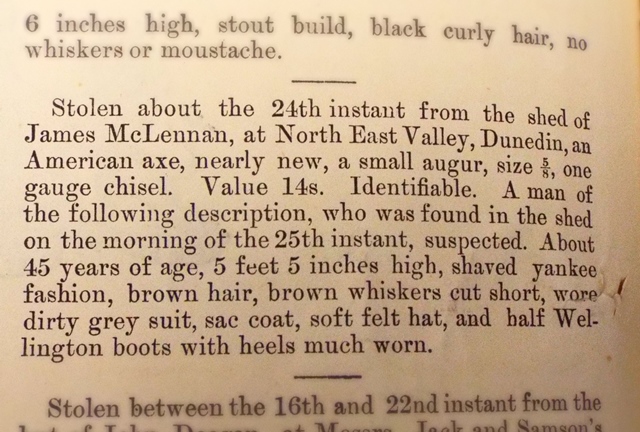

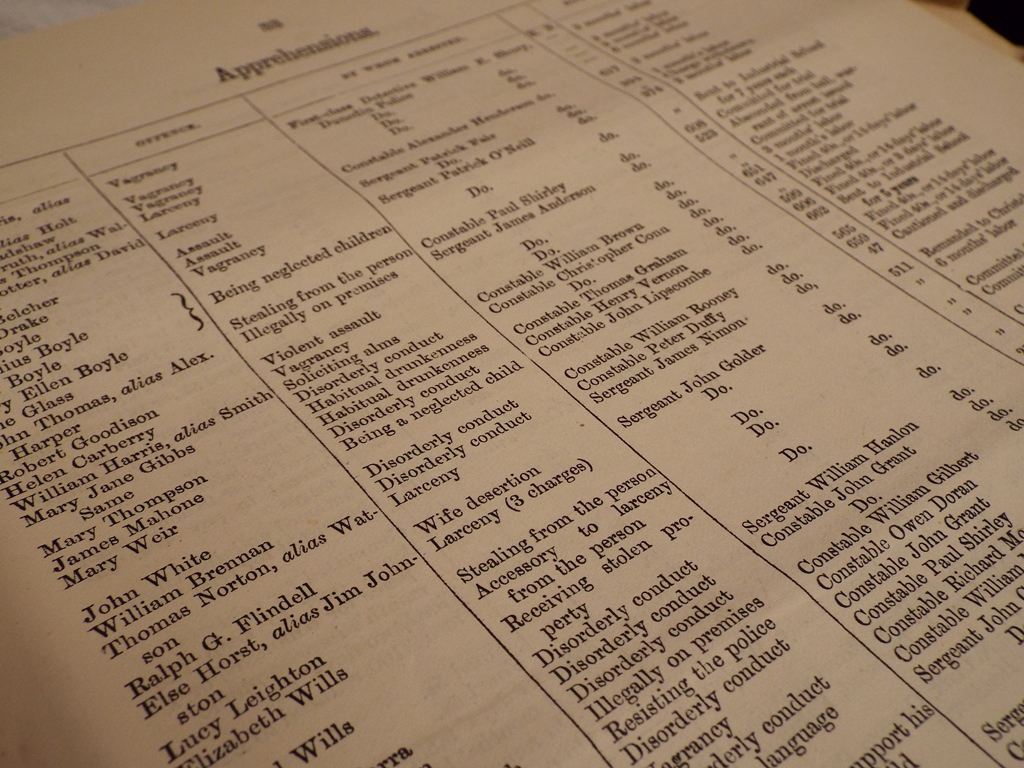

Throughout the yellowed pages, charges for larceny, lunacy, vagrancy, disorderly conduct and habitual drunkenness abound. Other cases illuminate societal concerns: “furious riding” and “sly grog-selling” were both frowned upon, as was “occupying a house frequented by reputed thieves.”

Anxiety for the wellbeing of citizens is also apparent, with men charged for deserting their wives and for failing to support their mothers. Children, too, could find themselves arrested for “being neglected,” or for “being a criminal child;” the usual outcome of this was a sentence of some years at the Industrial School. Women tended to attract charges of vagrancy and drunkenness, whereas men were the usual perpetrators of a wider range of offences. Serious and violent transgressions also arose, among them assault with intent to commit rape, attempted suicide and murder.

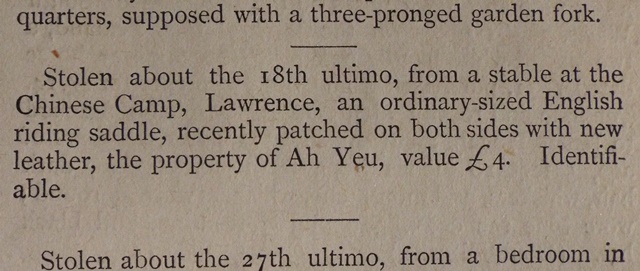

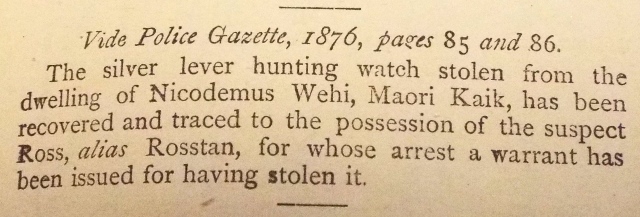

Māori appear infrequently over the period surveyed, but Chinese names are occasionally interspersed amongst those of British and European origin, both as perpetrators and as victims of crimes.

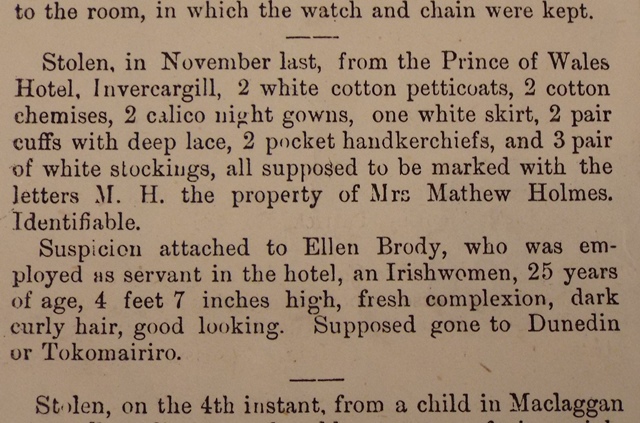

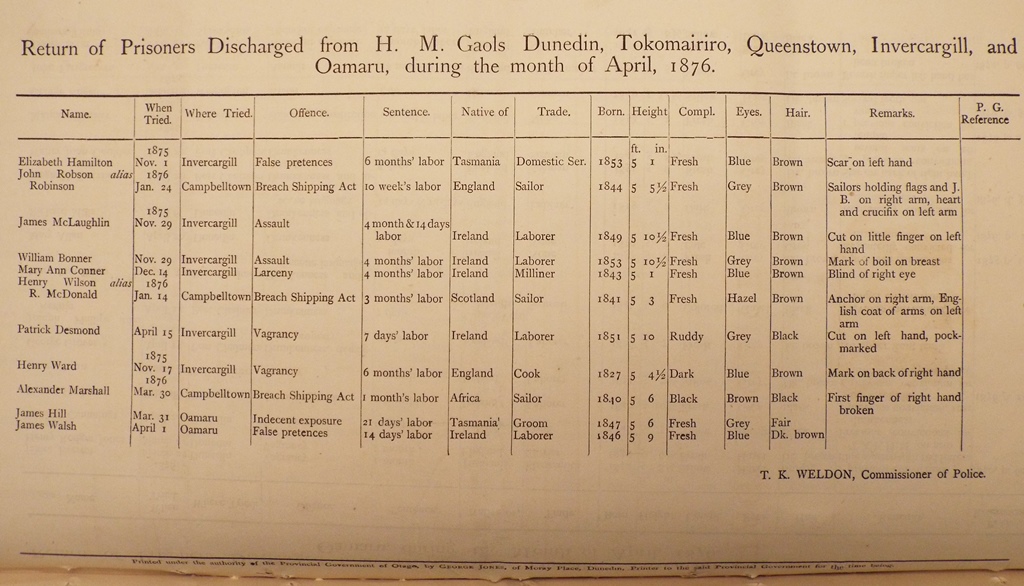

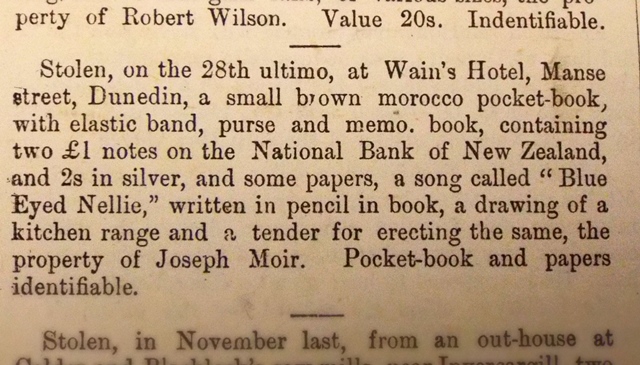

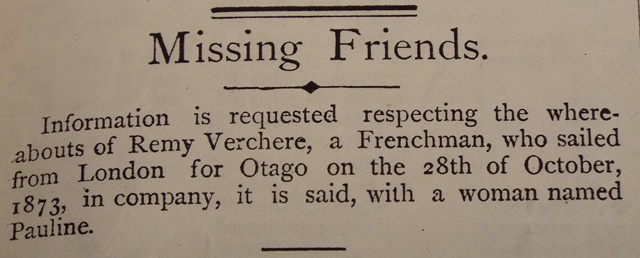

The pages are filled with reports of items stolen (watches, horses and money dominate), warrants issued, and inquest findings. Lost and found property is recorded, as are “missing friends” such as Edward Chaplin described above. Offenders apprehended are listed alongside their punishments, and further tables record those arrested, tried, and discharged from prison during the past weeks. Descriptions of former prisoners are provided, with notes made of any distinctive features such as tattoos or physical abnormalities.

Submissions to the Gazette range from the mundane through to the grim and distressing. Some cases appear trite or even comical to the modern eye. Yet, on reflection, they show us the anxieties, concerns, and troubles of those living in the earlier days of our province.

Every entry in the Gazette hints at a richer story on the part of both victim and perpetrator. I can’t help but wonder at the implications and outcomes of certain cases, and if those with missing friends were ever reunited.