Post researched and written by Collections Assistant (Publications), Emma Scott

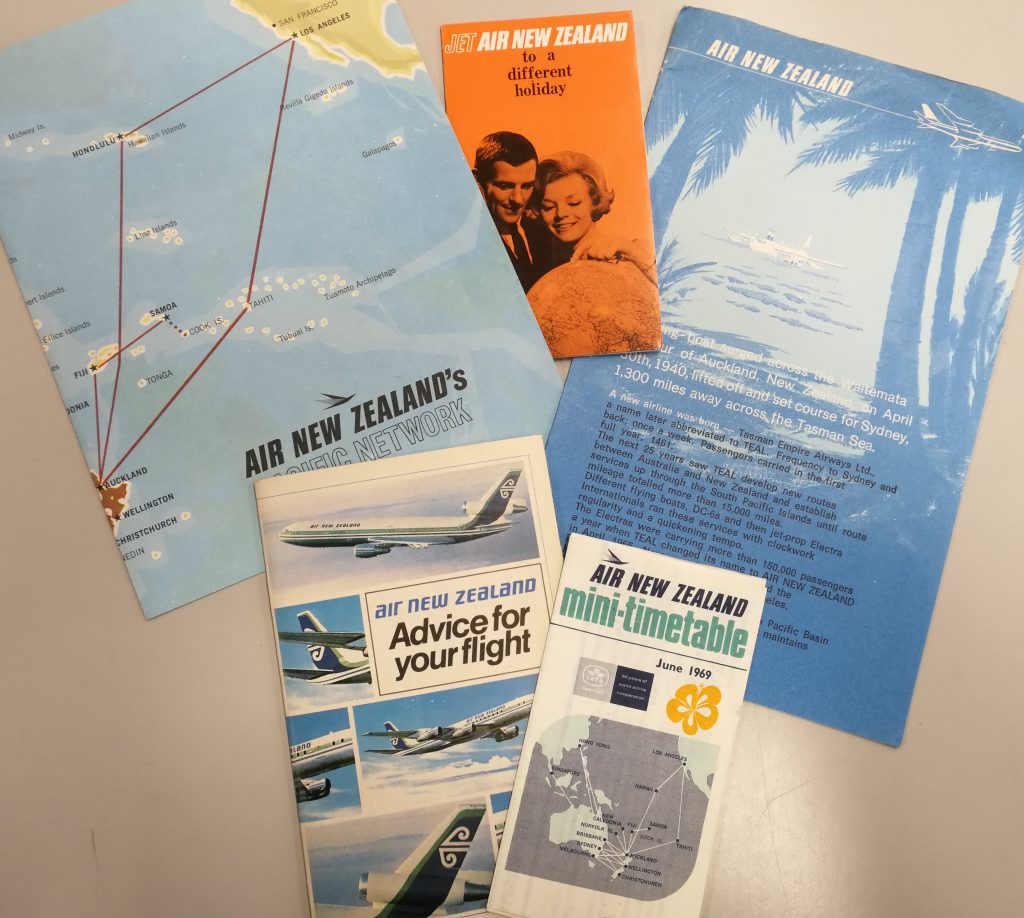

Prior to the COVID-19 lockdown, the Publications staff at the Hocken discovered a booklet in the collection titled Advice for your flight [1] which was produced by Air New Zealand. Advice for your flight was designed to answer any questions a new traveller may have and was also an advertisement to fly on the DC-8 and the DC-10 jets. The booklet doesn’t have a date, but upon consulting an excellent publication titled Conquering Isolation: the First 50 Years of Air New Zealand by Neil Rennie [2], I was able to determine that the earliest the booklet could have been produced was 1973, which was when the DC-10 began service in the Air New Zealand fleet. Maybe it is my ever increasing wanderlust since the pandemic, but on returning onsite after lockdown, this little booklet sparked an interest in me to do some research into the jet age of air travel in New Zealand during 1960s and 1970s.

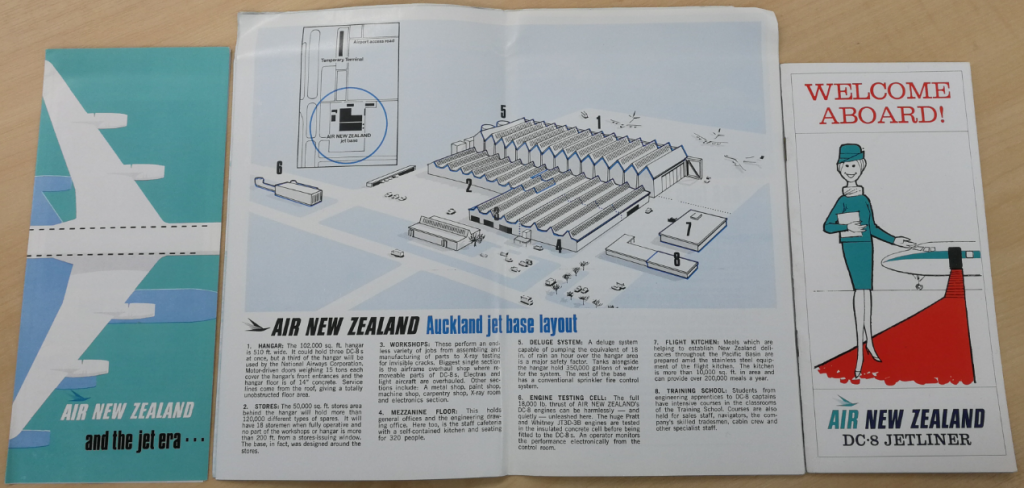

1965 was a very momentous year for Air New Zealand. For starters they changed their name from TEAL to Air New Zealand. Tasman Empire Airways (TEAL) was established by the New Zealand, the United Kingdom and Australian governments to provide a trans-Tasman air link. When the New Zealand government bought the remaining 50% share owned by the Australian government in 1962, TEAL officially became a fully New Zealand owned and operated air carrier. The 1962 TEAL annual report states “TEAL is an all-New Zealand undertaking whose first loyalty is to New Zealand and whose cause we are all proud to serve.” [3] The name change coincided with the building of a new airport in Māngere, a new jet base at Auckland airport costing $2 million dollars and the purchase of three DC-8 jets ($5 million dollars each) which were introduced into service later in 1965.

Our Ephemera collection contains several pamphlets advertising the DC-8 and Auckland’s new jet base.

One of Air New Zealand’s pamphlets; Air New Zealand and the jet era states: “The Douglas DC-8 Series 52 is the latest version of a line of DC-8 jets which has been proven for over six years in commercial operation. Powered by four JT3D-3B Pratt & Whitney engines, the Air New Zealand DC-8 will speed up to 159 passengers at 10 miles per minute in superb luxury”. This was quite a step up from the L-188 Electras which could carry 71 passengers at 400 miles per hour compared to the DC-8 which could travel up to 540 miles per hour.

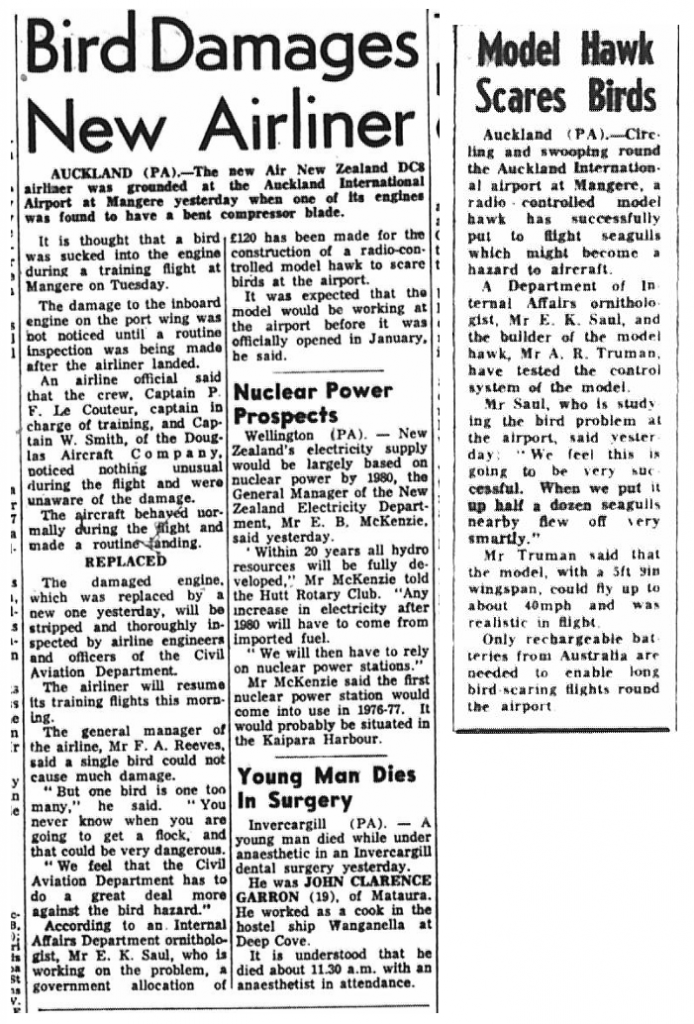

The introduction of the new DC-8 jets didn’t go entirely according to plan, with a bird being sucked into the engine of one of the DC-8’s during a training flight on the 11th of August 1965 which caused £1000 worth of damage. To avoid this happening again, the government allocated £120 for the construction of a radio-controlled model hawk to scare away the birds. The hawk was tested in October 1965 with positive results. [4] [5] [6]

Not long after being in service, on the 4th of July 1966, a DC-8 jet on a training flight crashed and killed two of the five men on board; Captain Donal McLachlan and flight engineer Gordon Keith Tonkin. [7] It was determined that “an inadvertent application reverse engine thrust” during take-off caused the crash. Minister of Civil Aviation J.K. McAlpine went on to assure the public that there “were no grounds for public concerns on the score of passenger safety” as the controls that were manipulated would not be used during a take-off with passengers on board. [8]

Despite initial problems, Neil Rennie states in Conquering Isolation on page 104 that: “the DC-8 was the first pure jet in the Air New Zealand fleet which really shrank the world.” “The Jet flew smoothly above or around most bad weather”. One DC-8 was even kept on to serve for seven years after the others were phased out in 1981, as a freighter and carried everything “from computers to live deer”. The success of the DC-8 justified purchasing three DC-10s in 1970. The DC-10 could carry 268 passengers, which dramatically reduced the costs per passenger for Air New Zealand.

With the introduction of the DC-10 came some new uniforms for Air New Zealand hosts and hostesses. The new uniforms were designed by New Zealander Vinka Lucas. The hat was also designed by New Zealander Wynne Fallwell of Mr Wyn Originals. You can see some beautiful photographs and read a detailed description of the uniform on the New Zealand Fashion Museum Website.

Sadly, most New Zealanders remember the DC-10 for one of New Zealand’s biggest tragedies. On the 28th of November 1979, DC-10 flight TE901 didn’t return to Christchurch after a sightseeing flight to Antarctica. The wreckage of the plane was discovered the following day on the slopes of Mt Erebus. All 257 passengers and crew were killed. [9]

There was a significant amount of controversy over the crash. Chief Air Accident Investigator Ron Chippendale’s report into the crash stated that the probable cause of the accident was “the decision of the captain to continue the flight at low level toward an area of poor surface and horizon definition when the crew was not certain of their position”. [10]

On the 21st of April 1980, Justice Peter Mahon was chosen as the commissioner for a Royal Commission of Inquiry into the disaster. Peter Mahon’s report listed several factors and circumstances which contributed to the cause of the Erebus crash. On page 159 of the report he states that in his opinion “the single dominant and effective cause of the disaster was the mistake made by those airline officials who programmed the aircraft to fly directly at Mt Erebus and omitted to tell the aircrew”. [11] [12]

We hold a number of items in our ephemera collection related to the sightseeing Antarctic flights including: breakfast and lunch menus for the flights, raffle tickets for the TE901 fatal Erebus flight and a promotional booklet titled The Antarctic experience.

Advice for your flight includes the usual kinds of instructions you would find on the Air New Zealand website now; like baggage allowances, insurance, passport and visa regulations. As per the title, the booklet also contains useful advice such as “fountain pens are prone to leak and should be emptied before travelling”.

Pages 7 and 8 of the booklet lists approximate weights of commonly worn clothing items to assist travellers in keeping their suitcases within the free baggage allowance of 30kg for first class and 20kg for economy. A woman’s 3 piece wool suit is listed as weighing 1lb 8 oz, her live-in set 8 oz and her Winter house coat 6 oz. A man’s dark worsted suit was listed as weighing 3 lbs, his sports jacket 2 lb 12 oz and his shoe cleaning kit 1 lb.

If you were considering purchasing duty-free goods there is a handy guide in the back of the booklet listing what customs will allow into various countries. When travelling home to New Zealand you were allowed to carry 200 cigarettes or 50 cigars or ½ a pound of tobacco. You could also carry 1 quart of Wine and 1 quart of spirits. When travelling to Australia you could carry 400 cigarettes or 1 pound of cigars or 1 pound of tobacco, 4 quarts of Wine or 4 quarts of spirits.

While we are limited to domestic travel, at least for the moment, we can use the Hocken’s collections to imagine ourselves flying off to exciting overseas destinations. As our collection primarily consists of New Zealand material, you can also get some inspiration for your next New Zealand getaway.

References:

[1] Air New Zealand. Advice for Your Flight. Air New Zealand, 1973/1974?.

[2] Rennie, Neil. Conquering Isolation: The First 50 Years of Air New Zealand. Auckland: Heinemann Reed, 1990.

[3] TEAL. Annual Report and Accounts, 1962, p. 3.

[4] Otago Daily Times. “Bird Damages New Airliner.” Otago Daily Times, 12 Aug. 1965, p. 3.

[5] Otago Daily Times. “Bird Damage Costs £1,000.” Otago Daily Times, 21 Aug. 1965, p. 5.

[6] Otago Daily Times. “Model Hawk Scares Birds.” Otago Daily Times, 21 Oct. 1965, p. 1.

[7] Otago Daily Times. “Two Killed In Crash At Auckland Airport.” Otago Daily Times, 5 July 1966, p. 1.

[8] Otago Daily Times. “Reversed Engine Thrust Caused Crash of DC8.” Otago Daily Times, 21 July 1966, p. 1

[9] “The 1979 Erebus Crash” Te Ara. Last modified 17 December 2020. https://teara.govt.nz/en/air-crashes/page-5

[10] Office of Air Accidents Investigation. Aircraft Accident Report No.79-139 Air New Zealand McDonnell-Douglas DC-10-30 ZK-NZP Ross Island Antarctica 28 November 1979, p.35

[11] Mahon, Peter. Verdict on Erebus. Auckland: Fontana Paperbacks, 1985.

[12] Report of the Royal Commission to inquire into The Crash on Mount Erebus, Antarctica of a DC10 Aircraft operated by Air New Zealand Limited 1981

Air New Zealand. Annual Report, 1966-1980.

Otago Daily Times. “Airliner Lost In Antarctica.” Otago Daily Times, 29 Nov. 1979, p. 1.

Otago Daily Times “Grisly Task for Rescue Team.” Otago Daily Times, 30 Nov. 1979, p.1.