For Māori, place and place names act as constant reminders not only of where one is, but of who one is – without one the other does not exist.

Māori named the landscape as a way of emphasising claim to the land, to describe features, to immortalise people or events for historic or spiritual reasons and to celebrate cultural icons. In the absence of a written language, naming the land committed the landscape to memory. The events and characteristics associated with the landscape anchor it and give it a durable reference, as well as floating access to a huge range of oral information. In this way, Māori place names are peopled and named at a variety of levels.

The wealth of information within the maps and manuscripts on display in the Hocken foyer, were created by Māori in the post-European era, for reasons other than what Māori needed to know about or to express to themselves. Information was offered to, or maps were drawn at the request of British officials, surveyors and other Europeans to explain the lay of the land and its access routes, the location of resources, flat land, good soil, fishing grounds and safe anchorages. Māori who created the maps and provided the information within the manuscripts could clearly describe spatial relationships and had a fundamental sense of where they were geographically, preserving as much tightly compacted and coded material by reducing complexity to an information-rich abstract. European needs may have defined the focus of the materials on display, but not the instinctive style nor the acute knowledge of the land that is within them.

The Māori who authored these maps and manuscripts provided information about the land via a conversation, a korero. It was the supporting richness that existed within the oral tradition that embedded the layers of information within the land, making the Māori landscape a human landscape filled with stories. Within both the maps and the manuscripts on display, one can readily visualise this. The talking, the drawing of lines to illustrate, the conferring, the calling on a huge floating resource of story, song, experience, myth, spirituality, history, learned detail, relationships, genealogies, memories, paths walked, food resources gathered and the feel and smell of the presence of the land.

Items on display include:

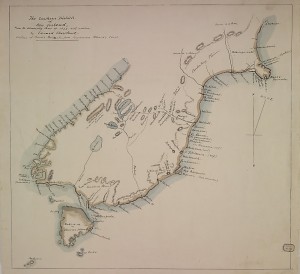

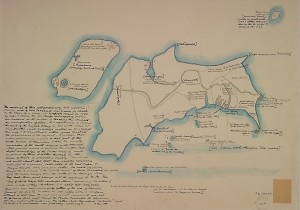

MAPS

The Southern Districts of New Zealand: From the Admiralty Chart of 1838. Hocken Collections. Illustration above.

New Zealand map drawn by Chief Tuki-tahua and Huruhuru, 1793. Hocken Collections.

Map of lakes in the interior of Middle Island from a drawing by Huruhuru, 1844. Hocken Collections.

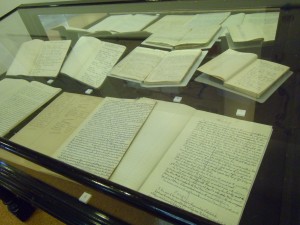

MANUSCRIPTS

Beattie, James Herries. 1935. Note book containing notes on Maori place names and folk-lore. MS-582/E/4.

Beattie, James Herries. 1941. Nature and general information gathered between 1920 and 1940 from Maori. MS-582/W/11.

Beattie, James Herries. General Information, book 3. 1942. MS-582/E/13.

Beattie, James Herries. General Information, book 5. 1953. MS-582/E/15.

Beattie, James Herries. Notebook entitled ‘Maori notes from notebook of Eruera Poko Cameron. 1935. MS-582/E/4.

Beattie, James Herries. Notebook of John Kahu. 1880-1882. MS-582/F/14/a.

Beattie, James Herries. Notebook entitled: Notes on South Island place names, mostly in Otago. N.d. MS-0416/001.

Post prepared by Jeanette Wikaira-Murray, Maori Resources Portfolio Librarian