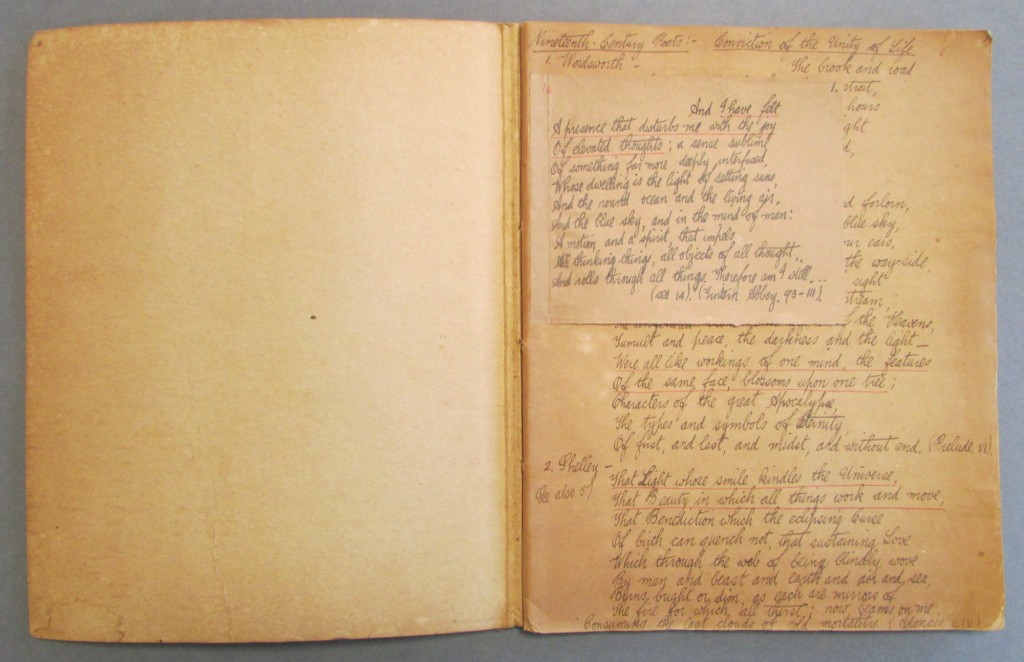

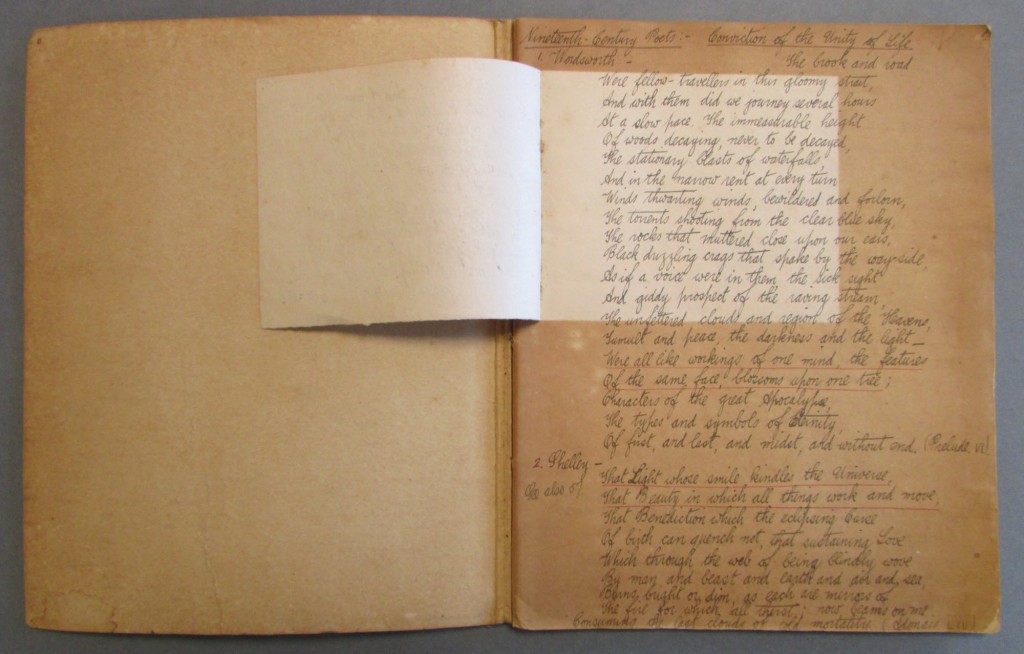

We often see the effects of acidification of paper on archival collections. Here is a particularly graphic example found in an old school notebook from the papers of the economist Allan George Barnard Fisher (1895-1976).

The cover of the volume is acidic board, and over the years the acid has migrated from the cover to the first page. A note inserted over part of the page has slowed the acid migration in that area, causing the paper underneath to be less damaged and lighter in colour. The subsequent pages in the volume have remained lighter.

From the late 19th century most paper was made from wood pulp. Wood pulp paper has what conservators call “inherent vice” and most will degrade over time becoming more brown and brittle. We now frequently see 20th century papers that are in much more discoloured and fragile condition compared to papers from the 19th century. Earlier papers were usually made from cotton fibres which do not age in the same way.

Acidification of paper happens when lignin (a fibrous component of wood) breaks down over time. As the lignin breaks down acids are produced that weaken the cellulose fibres of the paper, and make it yellow or brown and brittle. Like many chemical reactions, the acidification process is speeded up by heat, humidity and light. Leave a fresh newspaper outside in a sunny spot for a few days and see the effect of the sun, dew and daytime warmth for yourself!

Because of the almost universal use of wood pulp based papers across the world for much of the 20th century we are often presented with preservation conundrums like the A.G.B. Fisher volume pictured above. The staining could be removed by a professional conservator but the paper will remain weak and conservation treatment is expensive so we rarely have archives treated for this kind of damage. Our strategies for preserving paper are to improve storage conditions and reduce physical handling.

The conditions we store the collections in at the Hocken help slow the rate of deterioration. Air conditioning systems ensure the air in the storage areas remains at a constant temperature and humidity and dust is filtered from the air. Light is excluded by packaging in sturdy acid free folders and boxes, and lights are only turned on when staff need to work in the storage areas. The folders and boxes also provide physical protection to brittle paper, preventing bumps and tears caused by handling.

At home you can help slow the deterioration of your books and family papers by storing them out of direct sunlight, in a dry and clean place. Garages, sheds and basements are not good places for storing older historical material as they tend to be damp, dusty and light and temperature is uncontrolled.

Put historical papers and photos in clean new file folders and boxes. Don’t attempt repairs to tears with any kind of sticky tape, don’t have documents laminated as this causes irreversible damage.

Don’t put book cases directly against outside walls, leave a gap for air circulation between the book case and the wall or preferably put the book case against an internal wall.

The National Preservation Office at the National Library of NZ provides more detailed advice on the care of collections from their website.

https://natlib.govt.nz/collections/caring-for-your-collections/family-collections