Post researched and written by Dr Ali Clarke, Archives Collections Assistant.

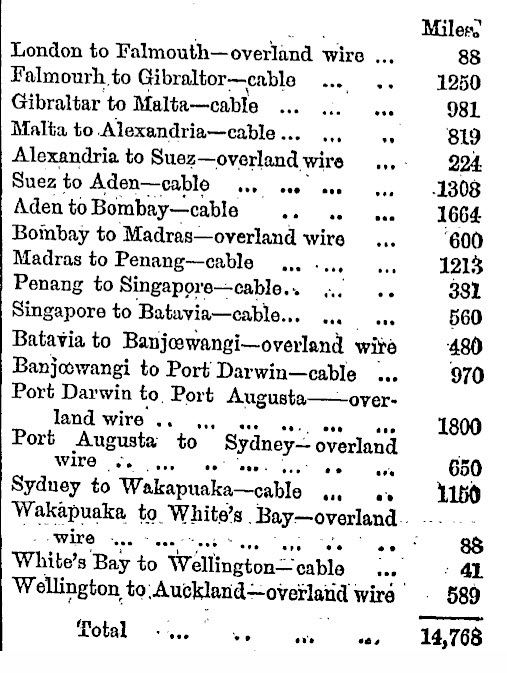

The installation of a submarine cable between Wakapuaka (near Nelson) and New South Wales in 1876 brought a new world of communication to New Zealand. People had already been able to send telegraph messages for a few years within the country. The first telegraph line appeared in 1862, linking Lyttelton and Christchurch, and in 1866 a cable went in under Cook Strait, linking the South and North Islands. Auckland was connected to points south by 1872. Once the new line to Australia opened, New Zealanders could send cablegrams around the world across an extensive network of overland wires and undersea cables.

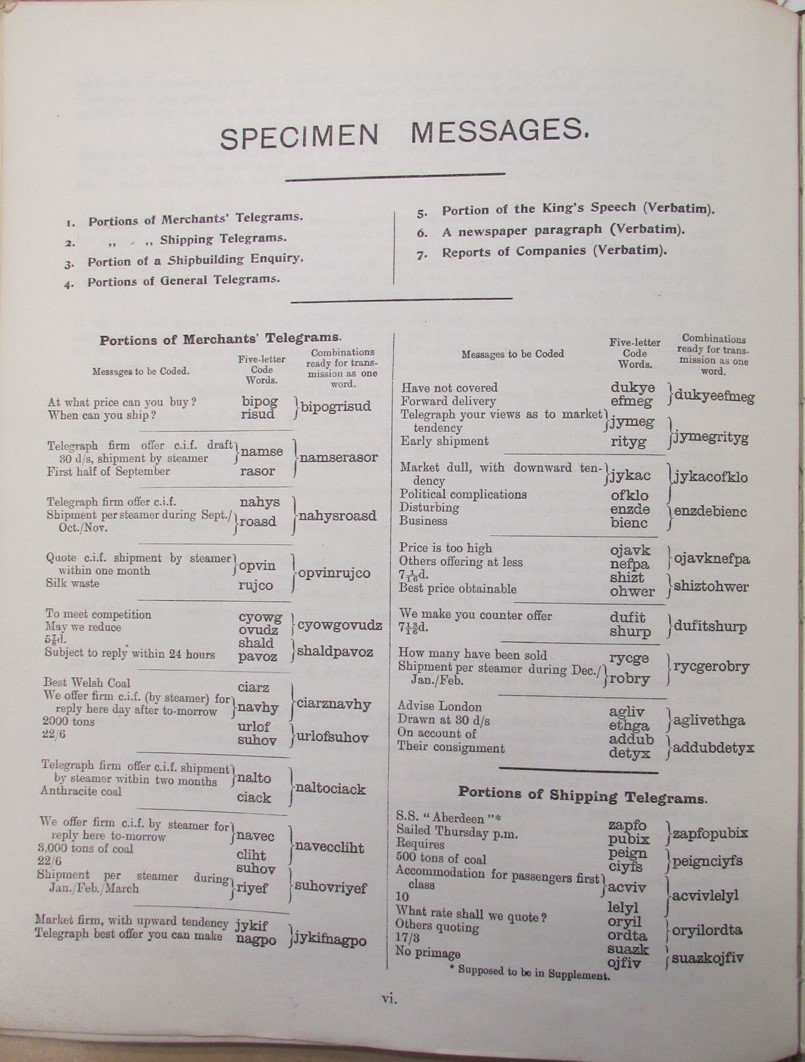

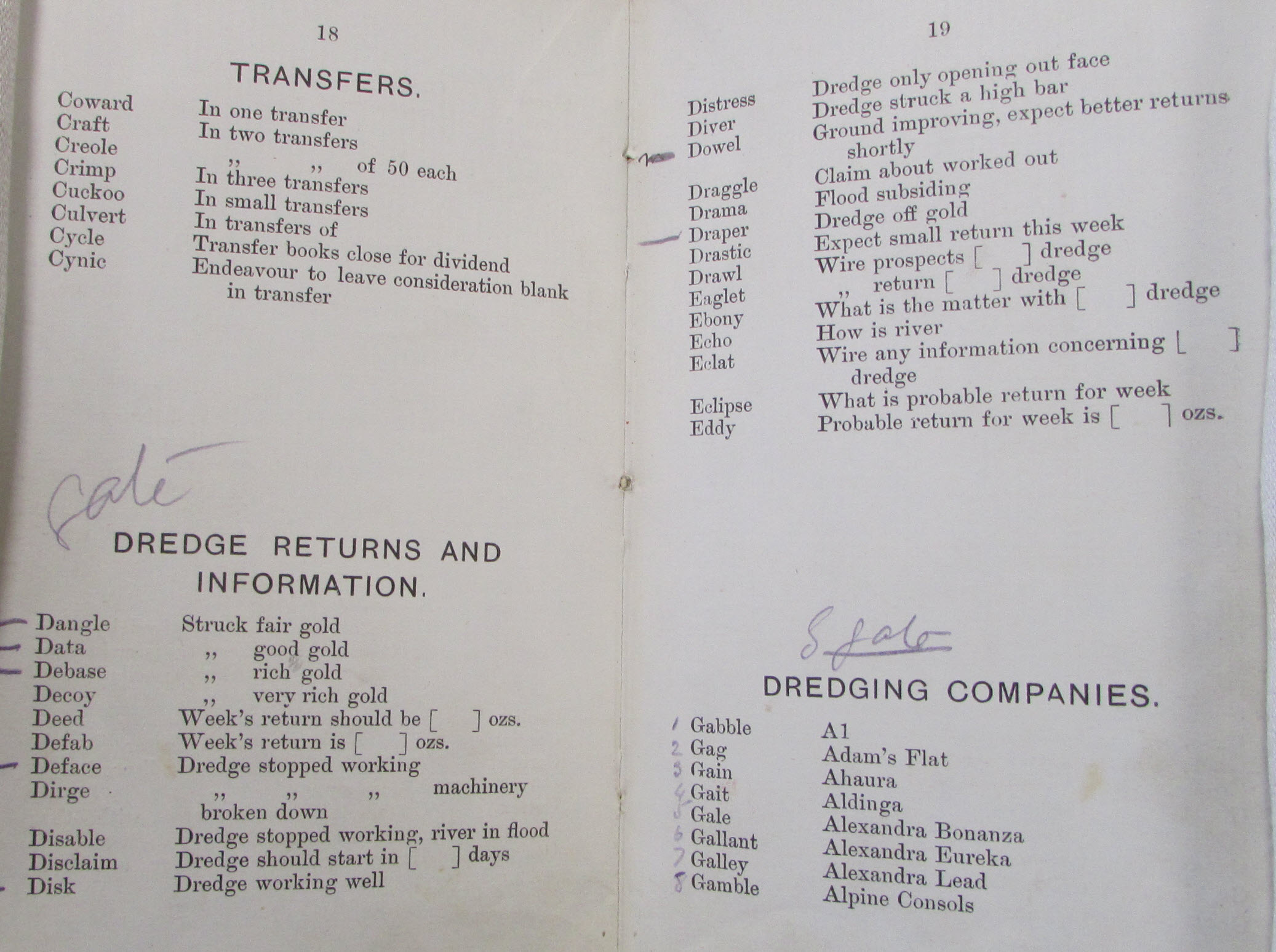

Specimen messages from Bentley’s Complete Phrase Code, 7th reprint of 1st edition (London: E.L. Bentley, 1921). From Briscoe & Co Ltd archives, MS-3300/117

This new form of communication was taken up with alacrity by government, news agencies and business. Meteorology services were important early users which had promoted the installation of the trans-Tasman cable – the cabling of weather data enabled more accurate weather forecasts. International news arrived in New Zealand more promptly. Before 1876 it had been cabled to Australia, then sent on to New Zealand by ship. For businesses involved in imports and exports, and the many with head offices or branches in other countries, the new speedy communication improved efficiency.

The route taken by a cablegram from London to Auckland, from Clutha Leader, 9 March 1876. Courtesy of Papers Past, National Library of New Zealand.

There were a couple of drawbacks to the use of cablegrams. First, they were expensive – the initial cost of a cable to Britain was 15 shillings per word (equivalent to about $120 in today’s money), though the price came down over time. Second, there were issues with confidentiality. Messages were seen by telegraph operators at both sending and receiving ends, as they translated the words and numbers into the dots and dashes of Morse code. Worse, messages might be intercepted en route: for instance, during the US Civil War of the 1860s, both Union and Confederate sides tapped each other’s telegraph messages.

People soon developed various encryption methods, which helped overcome both these disadvantages. Phrases could be made into a single word, making messages shorter and cheaper. Coding systems also made messages more secure. I became interested in these codes while working with some of the business archives at the Hocken – several of these include code books.

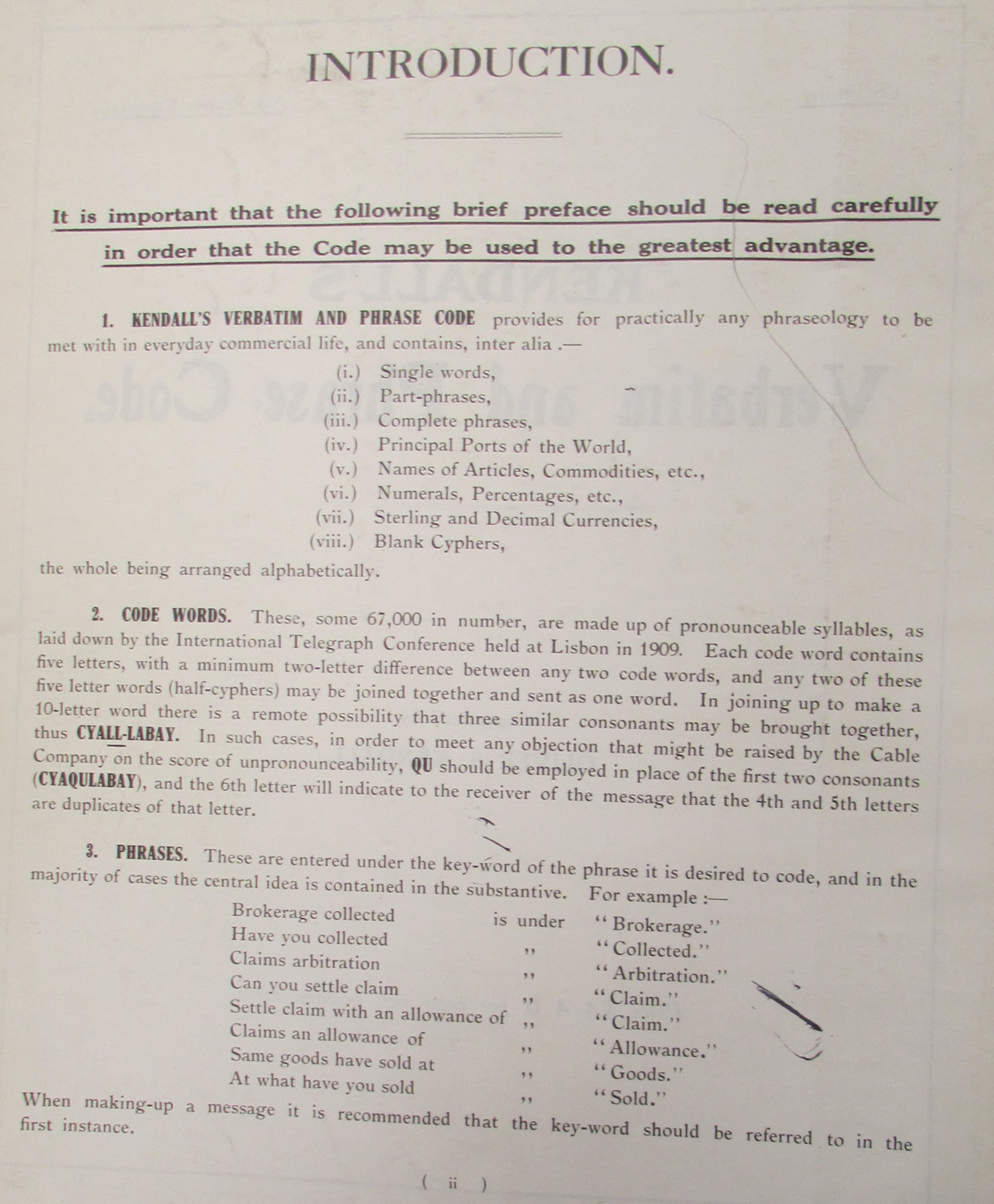

A generic code book such as Bentley’s Complete Phrase Code could be used for phrases or entire messages that weren’t highly sensitive. First published in London in 1907, Bentley’s converted phrases or individual words into 5-letter codes. Two of the 5-letter codes could then be combined into 10-letter ‘words’ to reduce the total words and make the message even cheaper to send. For example, the message “Market dull with downward tendency. Political complications disturbing business” could be sent with two ‘words’: jykacofklo enzdebienc. We hold a 1921 copy in the archives of Briscoe & Co Ltd. Another similar system was Kendall’s Verbatim and Phrase Code. We hold a copy of this in the archives of NMA Co of NZ Ltd.

Part of the introduction to Kendall’s Phrase and Verbatim Code (1921). From the archives of NMA Company of New Zealand Ltd, MS-4856/126.

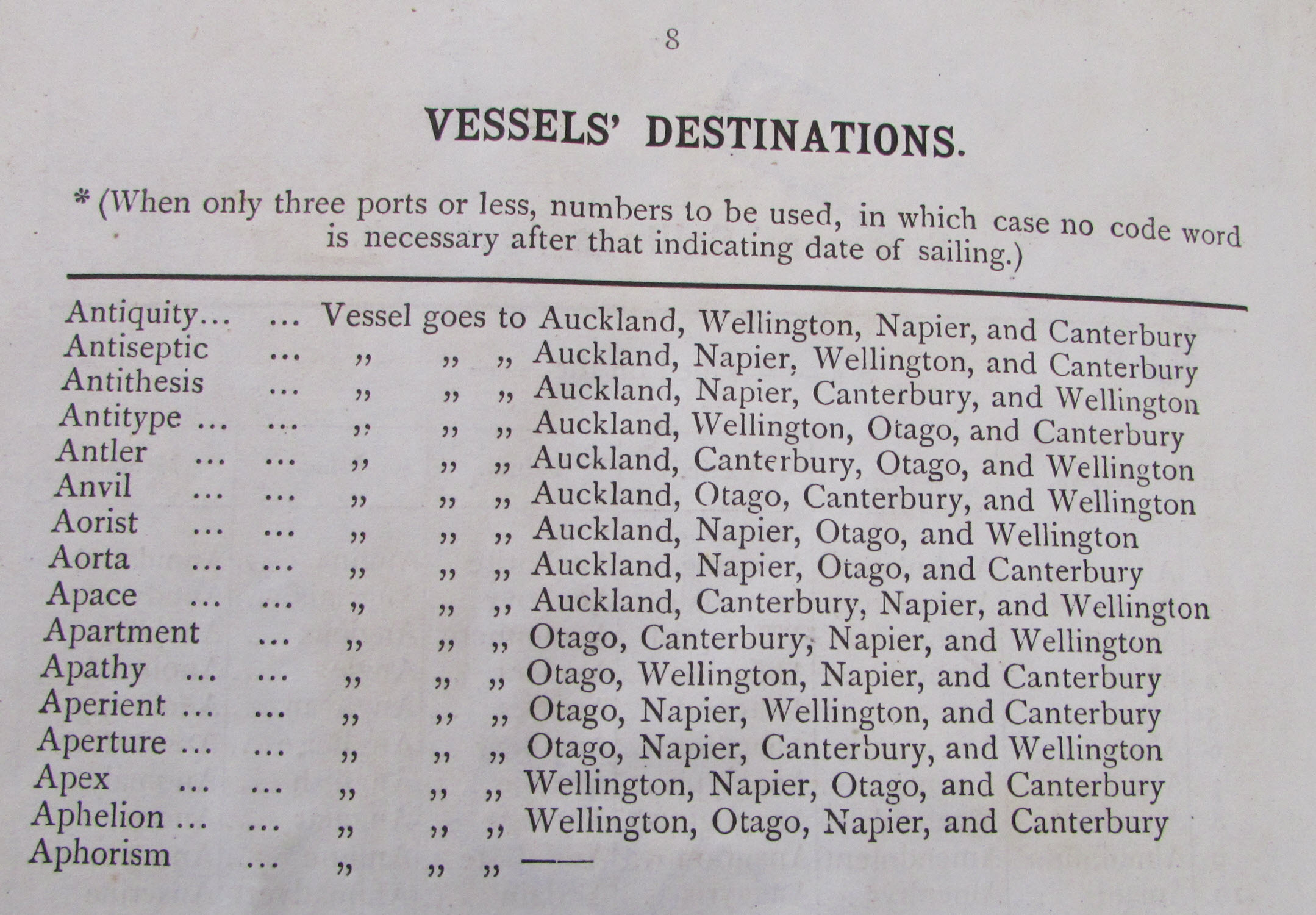

Codes like Bentley’s and Kendall’s used letter combinations that looked like gobbledegook, but others used real words. Their code books had alphabetical lists of words, matched to the terms to be coded. We have several examples of these in our archives and published collections – they are all codes specifically designed for particular businesses. Businesses developed private codes to replace or supplement the published code systems, in order to increase relevance and confidentiality. Examples of those using real words are Dunedin sharebrokers’ Sievwright Bros codes relating to investment and mining stocks, the New Zealand Railways code for messages between railway offices; and Shaw, Savill & Albion Co’s private telegraphic code for its shipping business.

From Sievwright Bros. & Co. Stock and Sharebrokers, Dunedin, Telegraphic Code for Investment & Mining Stocks (Dunedin: Mills, Dick & Co, c.1905).

Because the private codes were specific to a particular business, they were able to include long phrases in just one word. For example, in Shaw, Savill & Albion’s code, ‘pained’ translated as ‘At what price can you purchase Live Cattle of prime quality, suitable for freezing?’. In railway code, ‘briar’ stood for ‘Two-berth cabin for man and wife; if not available, reserve two seats together in first-class non-smoker. Will not accept berths in separate cabins.’ At Sievwright Bros, ‘ace’ meant ‘Buy for me when you think the market has bottomed’.

Codes for vessels’ destinations in Shaw, Savill & Albion Company, Limited, Private Telegraphic Code – No. 2. (London, 1890), from NMA Company of New Zealand Ltd records, MS-4856/124.

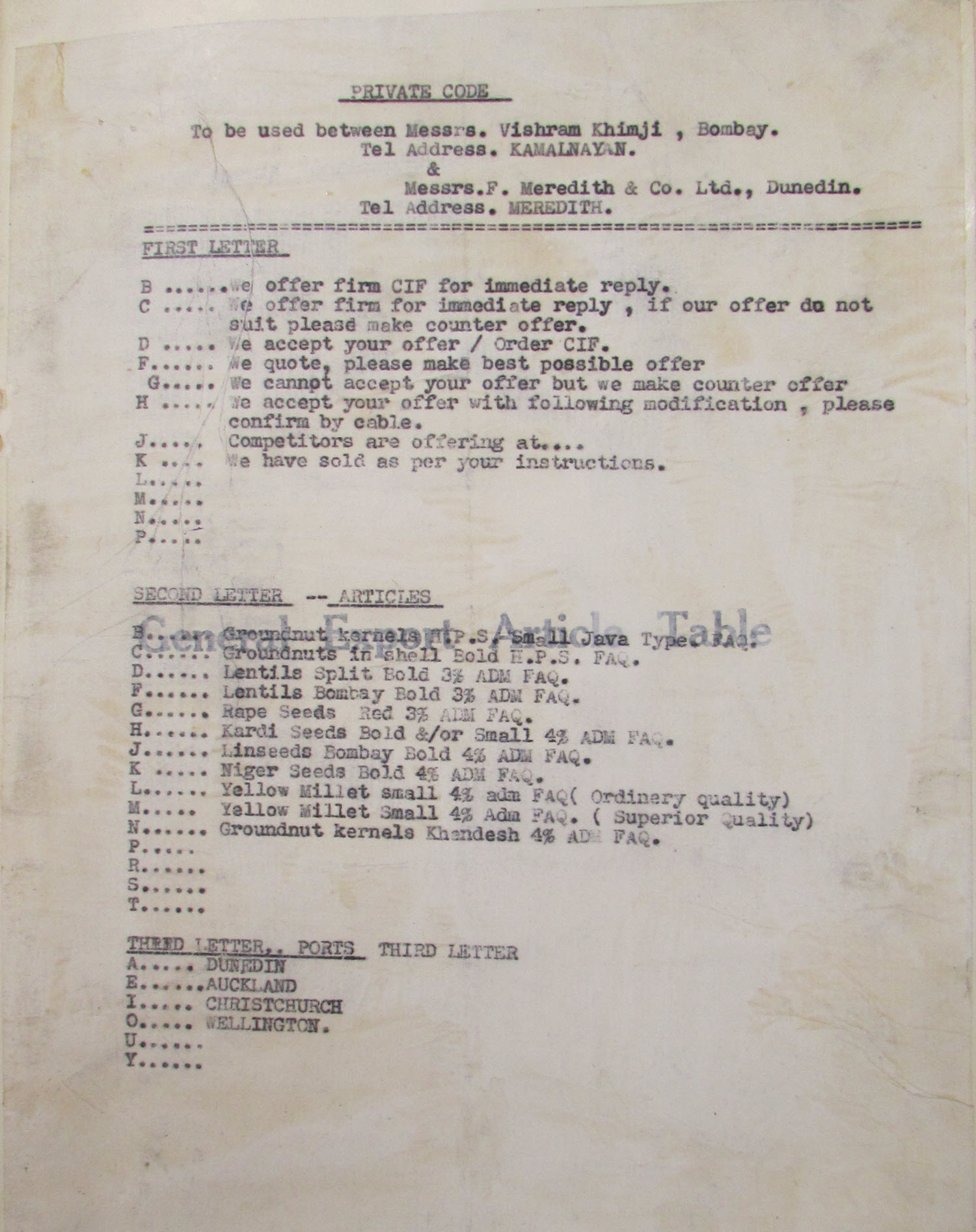

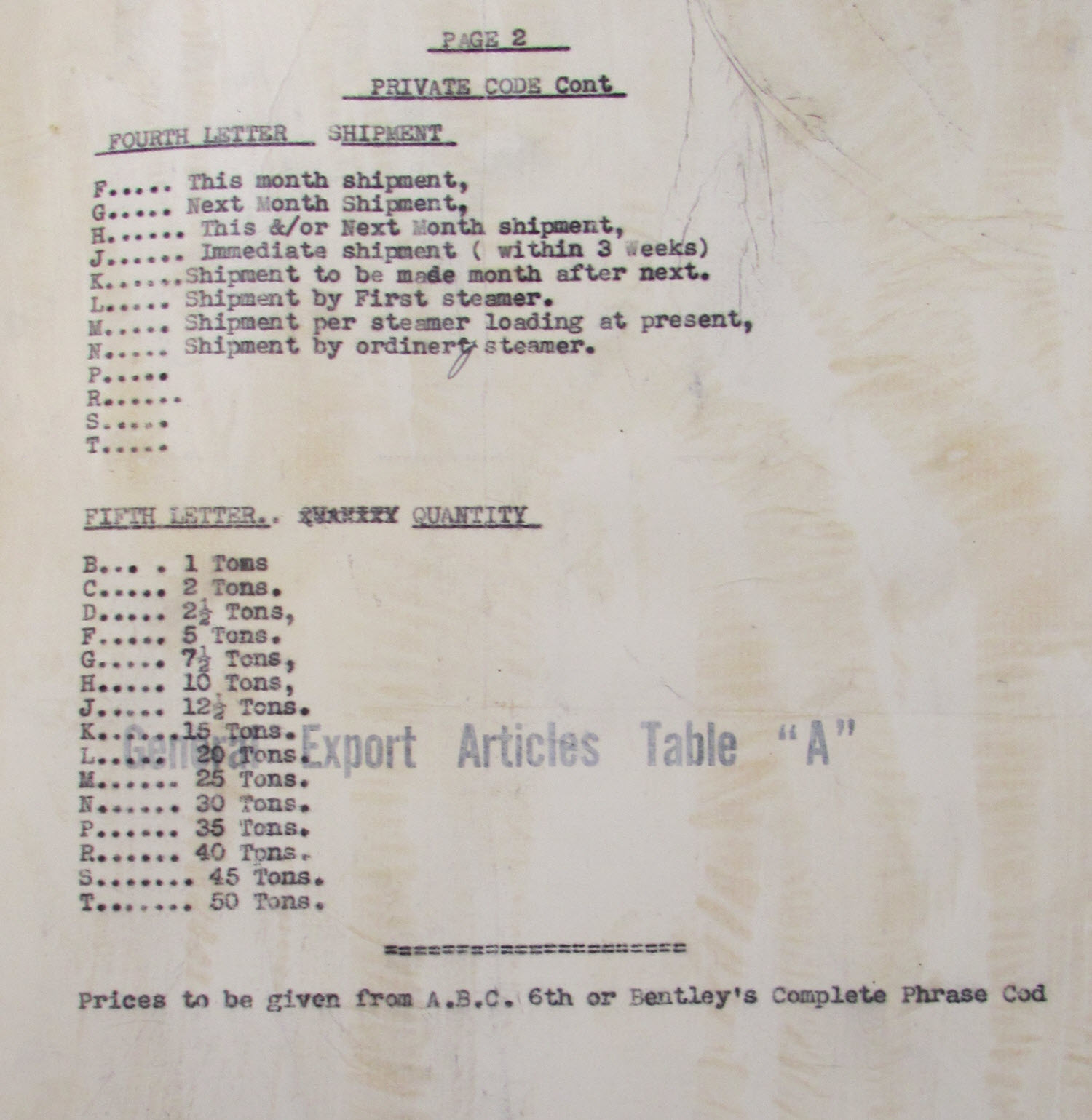

Some businesses went further with their private codes, so a single letter meant something. Their messages had a fixed format. A good example is the Dunedin importing company F. Meredith and Co. Ltd, which had individual codes for many different overseas firms. The illustrations below show the code they used for communicating with Messrs Vishram Khimji, Bombay. A lot of information could thus be conveyed with just one ‘word’. Note that they mixed this private code with one of the standard codes for messaging prices.

The private code used between importers F. Meredith & Co Ltd, Dunedin and exporter Messrs Vishram Khimji, Bombay. From F. Meredith & Co Ltd records, AG-265-13/002.

Page 2 private code used between importers F. Meredith & Co Ltd, Dunedin and exporter Messrs Vishram Khimji, Bombay. From F. Meredith & Co Ltd records, AG-265-13/002.

Another feature was the ‘condensor’, which converted 13 numbers, each with a specific meaning according to a private code, into 10 letters, or one cablegram ‘word’. Again, there are some good examples of this in the F. Meredith and Co. archives.

Of course secret codes could be useful for dubious as well as legal business, and reports appeared from time to time in local newspapers about discoveries of these, from Russian railway thieves with insiders informing them of valuable consignments with a special telegraphic code[1] (1909) to international drug dealers operating out of Shanghai with their own code[2] (1925). In 1912 a court case revealed that English suffragettes had their own telegraphic code where cabinet ministers and others were coded as trees and plants, and protest plans as birds.[3]

Whatever code was used, care needed to be taken to get it correct. Mistakes could be disastrous. In 1926 an unnamed New Zealand firm ordered from Calcutta 5000 bales of 50 woolpacks, when they intended to order 5000 woolpacks. They ended up with 50 years worth of supply, and other businesses had difficulty getting freight space from Asia because of the ‘exceptional cargo of woolpacks’.[4]

Thanks to Fletcher Trust Archives for permission to share items from the archives of NMA Company of New Zealand Ltd held in the Hocken Collections.

Notes

[1] Wairarapa Age, 21 July 1909.

[2] Waikato Times, 29 June 1925.

[3] Clutha Leader, 3 May 1912.

[4] Press, 5 July 1926.

References

Edward H. Freeman, ‘The telegraph and personal privacy: a historical and legal perspective’, EDP Audit, Control and Security Newsletter, 46: 6 (2012), 9-20.

A.C. Wilson, ‘Telecommunications – Early telegraphy and telegrams’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, 2010. https://teara.govt.nz/en/telecommunications/page-1

A.C. Wilson Wire and Wireless: A history of telecommunications in New Zealand 1890-1987 (Palmerston North: Dunmore Press, 1997).

National Library of New Zealand, Papers Past. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz