Post researched and written by Nick Austin, a General Assistant at the Hocken. He was the 2012 Frances Hodgkins Fellow and presented the exhibition The Liquid Dossier (16 February – 13 April 2013) at the Hocken Gallery.

Sitting and reading. These verbs take on a vocational significance at the Hocken; users of our material are called ‘readers’, after all. Louise Menzies’ exhibition at the Hocken gallery, called In an orange my mother was eating turned aspects of her research activity, as the 2018 Frances Hodgkins Fellow, into a ‘family’ of related artworks. Some of these works are paper-based, and most have text in them. Every one, though, is a kind of ‘material meditation’ variously on artists and their legacies – and other items of ephemera – some of which she encountered over the twelve months she lived in Dunedin and read at the Hocken.

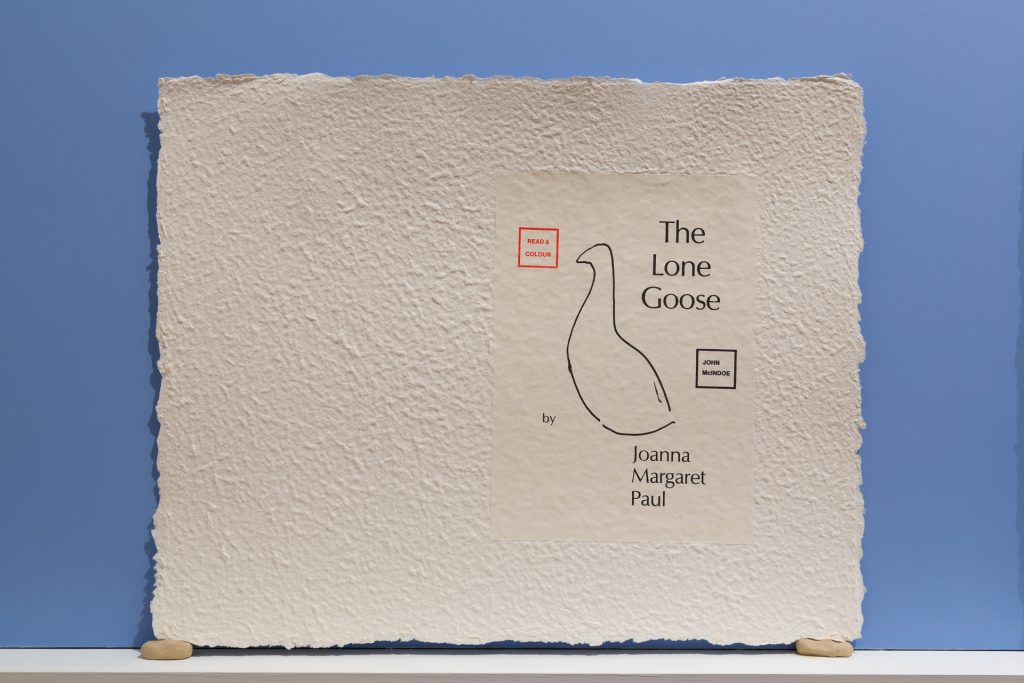

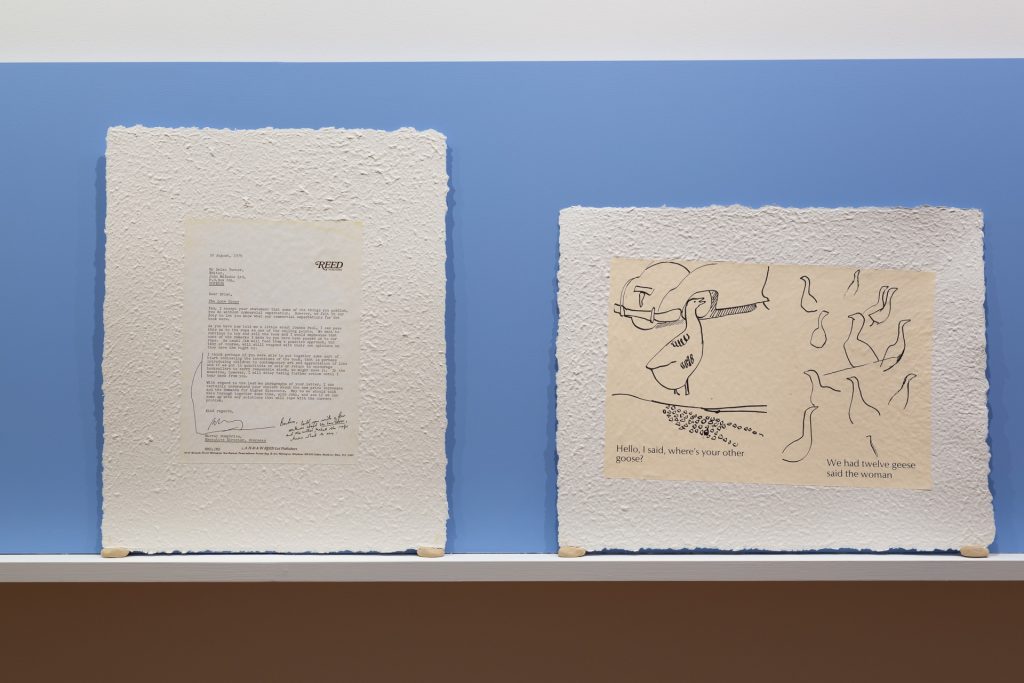

In the main gallery, a sky-blue shelf ran the full length of the longest wall. On its ledge, 24 individual sheets of paper, hand-made by Menzies. Adhered to each of these sheets is a risographed facsimile of one of two intimately related texts. One of these is a colouring-in book called The Lone Goose by the artist Joanna Margaret Paul (1945 – 2003). Published in 1979 by Dunedin-based McIndoe Press, it is an elliptical sort of story about the imagined friends of a goose waddling around our city’s Southern Cemetery. Paul complements her text with suitably – and wonderfully – provisional line drawings.

Louise Menzies, The Lone Goose (detail) 2019 Inkjet and risograph prints set in handmade paper Book pages: The Lone Goose by Joanna Margaret Paul, (Dunedin: McIndoe, 1979). With thanks to the Joanna Margaret Paul estate; Correspondence relating to The Lone Goose: MS-3187/058, Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago.

Louise Menzies, The Lone Goose (installation view) 2019, Inkjet and risograph prints set in handmade paper

While researching Hocken’s holdings of Paul material (we have quite a lot[i]), Menzies mistakenly requested a manuscript from our archives stack. Serendipitously, it contained correspondence between various players on the subject of The Lone Goose’s distribution. This cache of letters is the second text in Menzies’ work. On one hand, representatives from McIndoe’s distributors, Reed, just do not ‘get’ Paul’s book: “I fear the reps are going to be laughed out of the shops if they try and sell it.” But in response, Brian Turner (yes, the poet) in his capacity as Paul’s editor, is clearly peeved: “… I guess we [at McIndoe] do not move in the real world, as your reps do, and can hide our embarrassment at being ‘arty’.” While the letters present a bleakly familiar story of an artwork’s failure to lift-off in the marketplace (that the book is not exactly an artwork, does not really matter here), Menzies’ work is not depressing – it represents a significant new generation of Paul admirers.

Louise Menzies, The Lone Goose (detail) 2019 Inkjet and risograph prints set in handmade paper

It is easy to sense Paul’s importance to Menzies. (The title of the exhibition is a line from a Paul poem.) Both artists use language as a material to give form to thought. The way Paul’s work – her drawing, painting, film-making, writing – absorbs and reflects the places, people, things around her, is of high interest to Menzies. Paul was a Frances Hodgkins Fellow in 1983 so there is a kind of genealogical thread that connects them, too.

Frances Hodgkins. Given the reflexivity of this exhibition, it was sort of a no-brainer for Menzies to use Hodgkins (1869 – 1947) as a subject. It is surprising, though, how she did it. In one of the gallery’s side rooms sat three chairs: one a type you would see in halls and meeting rooms, dating from possibly the 1980s; one, a three-legged stool from about the 1960s; the other a contemporary type of adjustable office chair, with the brand name Studio on the rear of its back. This furniture shares the same provenance – all three were relocated from the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship studio, which is just across the road from the Hocken – and Menzies re-upholstered them in identical fabric.

Louise Menzies, Untitled (textile design no. II), 1925 (installation view) 2018 Digital print on textile

Louise Menzies, Untitled (textile design no. II), 1925 (detail) 2018 Digital print on textile

In the 1920s, Hodgkins was actively considering her return to NZ when, after years of struggle, she was offered a financial reprieve: a job in Manchester as a textile designer. While there are few extant examples of actual Hodgkins textiles (a silk handkerchief is held at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery), several of her gouache sketches are held at Te Papa. Menzies has printed the chairs’ fabric with one of these (digitally adapted) designs. Her work is named after its source, Untitled (textile design no. II), 1925. While the chairs serve as a memorial to the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship’s titular artist, they’re also a reminder of the stationary fact that every artist needs to make a buck somehow.[ii]

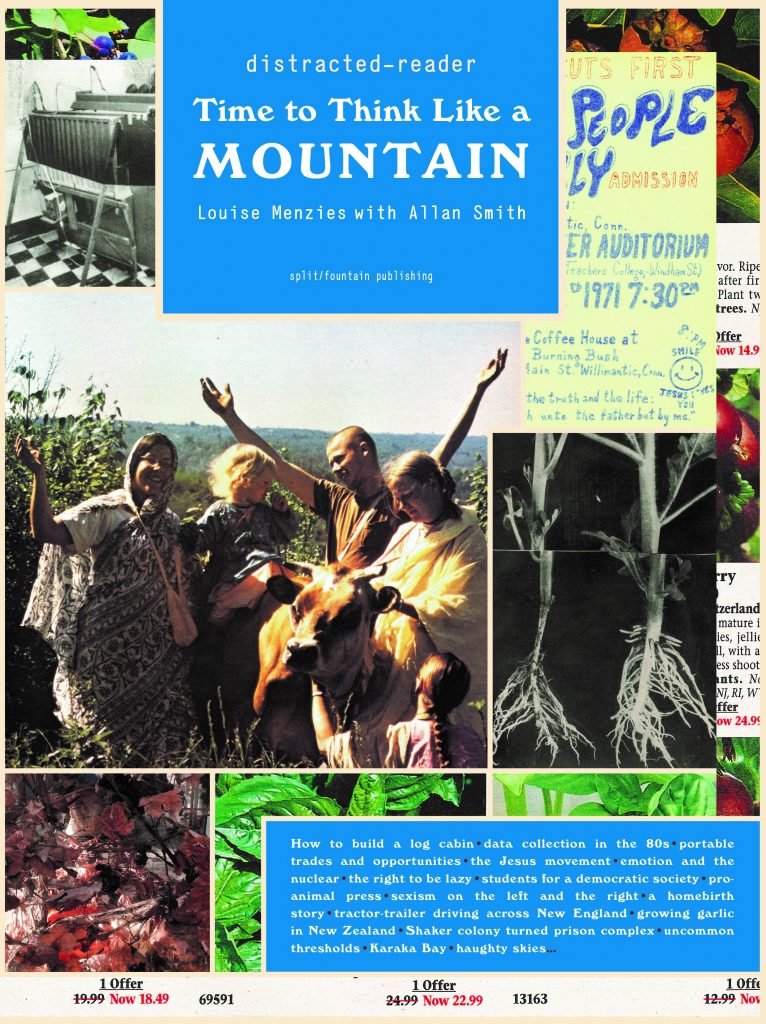

One thing that is different for an artist’s viability in the 21stCentury is the sheer number of residencies available to them. While the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship at the University of Otago remains one of the most generous offered in NZ (12 months on a Lecturer’s salary; free studio), this country’s artists frequently travel the world to participate in residency programs. In 2014, Menzies was invited to do a residency and exhibition at the University of Connecticut Art Gallery. During her six-week visit, she worked with the Alternative Press Collection (one of the largest collections of its type in the USA) within the Thomas J. Dodd’s Research Center. Over a much longer period, a resultant publication gestated. In fact, Menzies used the first part of her Hodgkins Fellowship to complete it.

Image: (publication cover) design by Narrow Gauge, images courtesy of Allan Smith, George Watson, Alternative Press Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Connecticut Library.

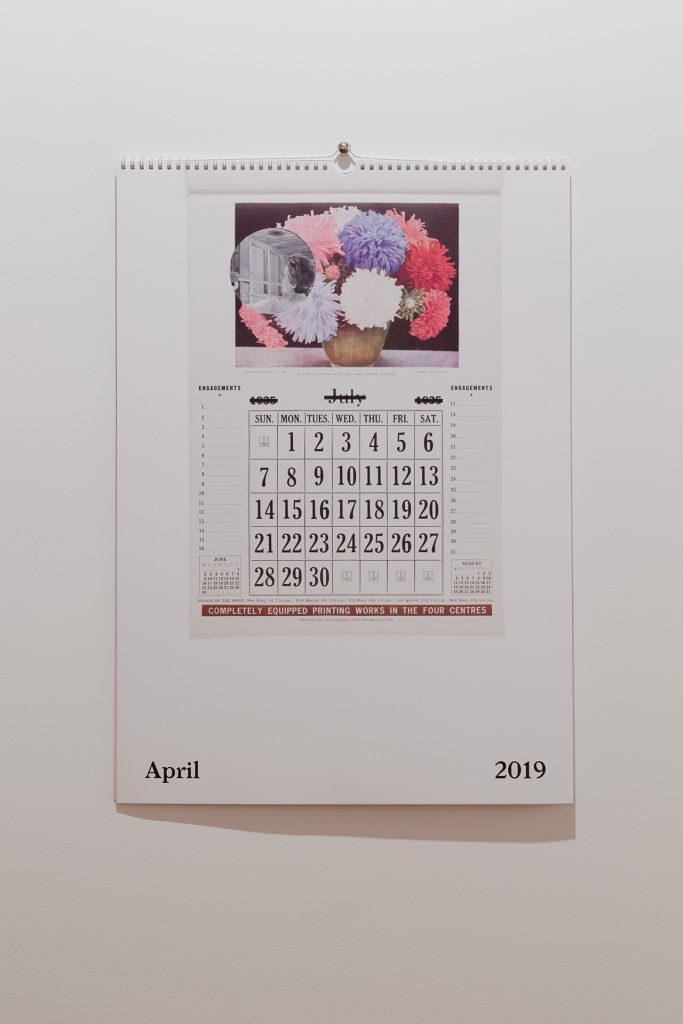

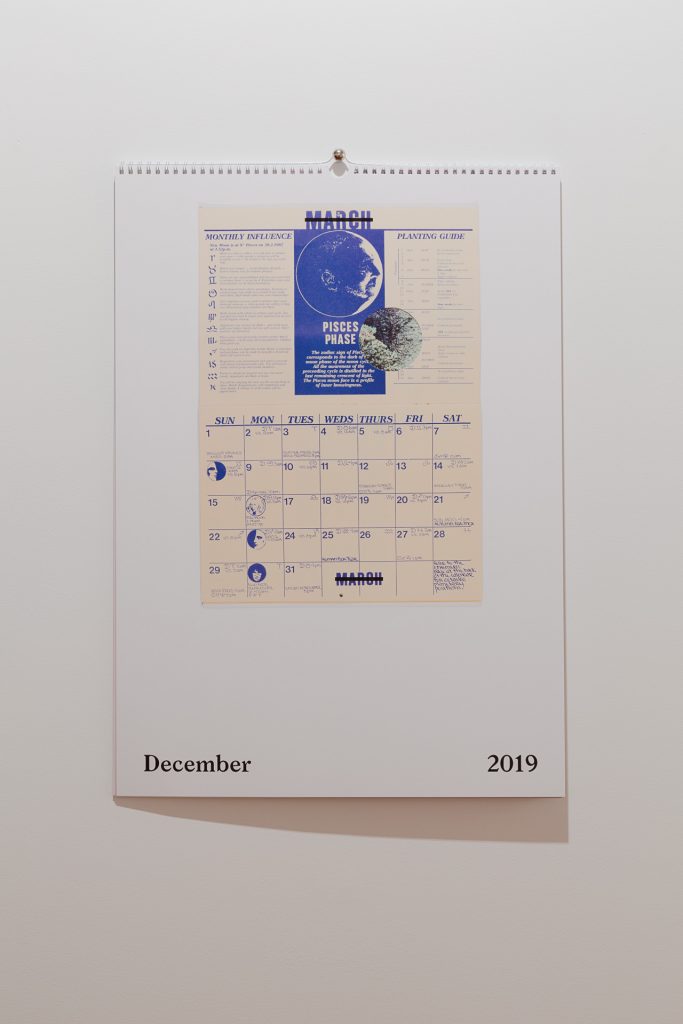

Time to think like a mountain, the finished book, was a segue into a publication-project that marked Menzies’ time as the Hodgkins Fellow. Coinciding with her Hocken exhibition and the end of her residency, Menzies and designer Matthew Galloway produced a calendar with source material from the Hocken’s Ephemera Collection. Each of Menzies’ calendar’s pages features an image of a calendar page from a past year whose dates fell on the same days as the present month’s. In yet another reflexive nod, Menzies’ calendar runs from February 2019 to January 2020 (the chronology of months over which the Fellowship takes place)… but the elegance of the idea is better explained with images:

Louise Menzies 2019 (detail) 2018 12-page calendar

Louise Menzies 2019 (detail) 2018 12-page calendar

Louise Menzies 2019 (detail) 2018 12-page calendar

It is fascinating how Menzies rematerialised different sources from the Hocken Collections as art; how she used her Fellowship as a subject; how she shows that time is not linear.

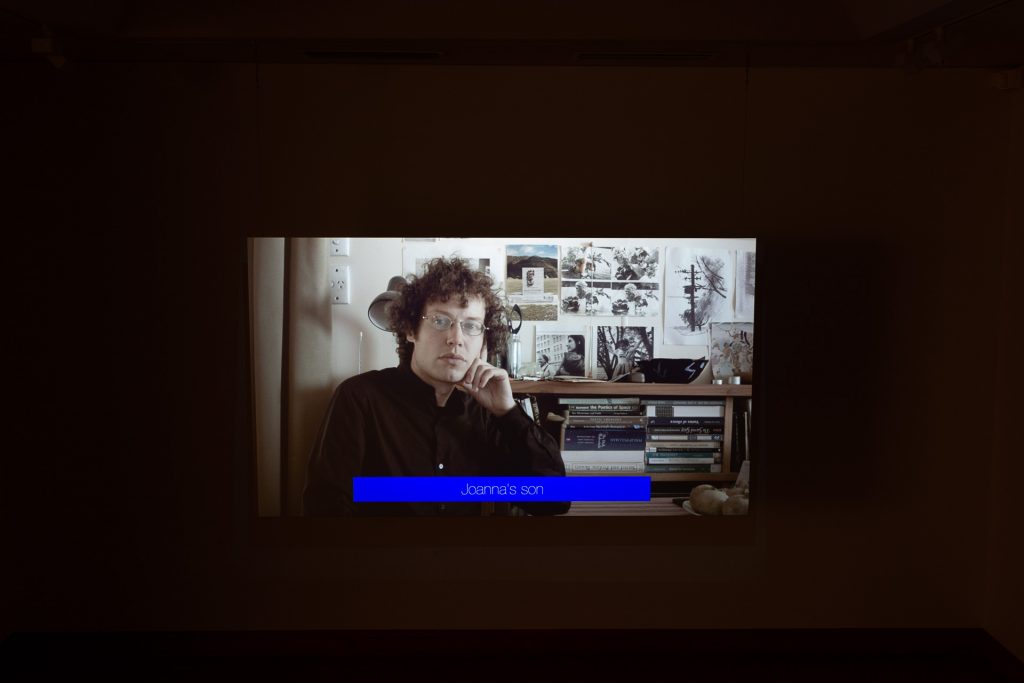

A video work that shares its title with the exhibition’s the video has many, intriguingly related, parts: an image of Paul’s son, Pascal, sitting for the camera; a soundtrack of the Ornette Colman song, The Empty Foxhole, featuring his then-10-year old son on drums; intertitles that contain a transcript of the complete Paul poem from which the exhibition took its name; an anecdote involving Menzies’ daughter…

Louise Menzies In an orange my mother was eating (installation view) 2019 Digital video, 3 min 21 sec

All photography unless otherwise credited: Iain Frengley

[i] We have nearly five hundred Paul items, including her paintings, drawings and sketchbooks.

[ii] Or, as another expatriate NZ artist has put it, “The artist has to live like everybody else.”