Post researched and written by Scott Campbell, Collections Assistant

Otago Daily Times, 22 November 1997, p3. “Ngai Tahu claims manager Anake Goodall points out the dotted line to Ngai Tahu chief negotiator Sir Tipene O’Regan, while Prime Minister Jim Bolger looks on. Minister in charge of Treaty of Waitangi negotiations Doug Graham adds his signature beside them.” The event happened at Kaikōura

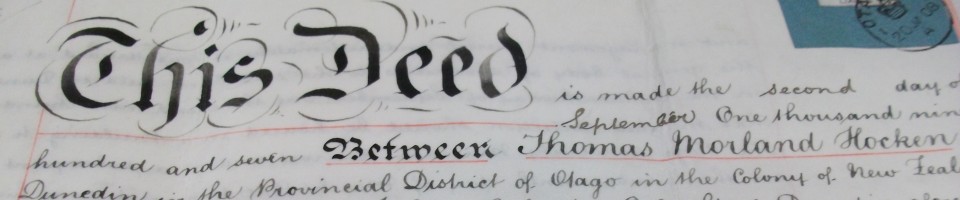

On 21 November 1997, representatives of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and the Crown gathered at Takahanga Marae in Kaikōura to sign the Ngāi Tahu Deed of Settlement. A copy of the Deed of Settlement occupies a good foot of shelf space in the Hocken’s publications stack. What was it all about? Why is the settlement significant? How can one learn more about it?

The signing of the Ngāi Tahu Deed of Settlement marked a milestone in the evolution of the relationship between Ngāi Tahu[1] and the Crown. For many years the Crown, in its relationship with Ngāi Tahu, had failed to uphold the standards required of a partner to the Treaty of Waitangi. Finally, as its representatives inked their names on the Deed, the Crown was making a commitment to doing something to make up for that.

Today is a day for New Zealanders to acknowledge Ngāi Tahu whānui past, present and future. The anniversary of the signing of the Ngāi Tahu Deed of Settlement provides an opportunity to remember the painful past, to pay tribute to the hard work and sacrifices made by generations of Ngāi Tahu to reach a settlement, and to celebrate the successes of Ngāi Tahu over the last 20 years. And even though the historical Treaty claims of Ngāi Tahu have been settled, the Treaty partnership and the responsibilities that go with it remain as important today as ever. Through reflection on the past, this anniversary also provides us with an opportunity to think about the mahi we can do to continue strengthening the Treaty partnership over the next twenty year period and beyond.

The Ngāi Tahu Treaty settlement – what is it, and why is it significant?

The signing of the Ngāi Tahu Deed of Settlement concluded negotiations between Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and the Crown for the settlement of all Ngāi Tahu historical Treaty of Waitangi claims. The Ngāi Tahu claims against the Crown – known as Te Kerēme to Ngāi Tahu whānui – spanned a time period reaching all the way back to the 1840s. Te Kerēme concerned the devastating cultural, economic and environmental impacts that stemmed from the Crown’s purchasing of almost all of the land held by Ngāi Tahu whānui prior to 1840 – some 34.5 million acres, covering much of the South Island – without honouring the promises it made to Ngāi Tahu when negotiating the purchases.

The Deed of Settlement recorded the agreements made between the Crown and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu during settlement negotiations. As part of the settlement, the Crown would make a formal apology to Ngāi Tahu whānui for its historical actions that breached the Treaty of Waitangi and its principles. The text of the Crown’s apology, recorded in the Deed in te reo Māori and English, acknowledged that the Crown “acted unconscionably and in repeated breach of the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi in its dealings with Ngāi Tahu in the purchases of Ngāi Tahu land.” The apology text went on to express the Crown’s profound regret and unreserved apology “to all members of Ngāi Tahu Whānui for the suffering and hardship caused to Ngāi Tahu, and for the harmful effects which resulted to the welfare, economy and development of Ngāi Tahu as a tribe.”[2]

The Deed of Settlement also detailed a redress package that the Crown agreed to provide to Ngāi Tahu “in recognition of the mana of Ngāi Tahu and to discharge the Crown’s obligations to Ngāi Tahu in respect of the Ngāi Tahu Claims.” [3] The package, valued at $170 million, included transfer of Crown properties and forestry assets to Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, vesting of significant sites in Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, and provisions relating to mahinga kai. As part of the settlement, the Crown recognised the original name of New Zealand’s highest mountain, agreed to officially rename it Aoraki/Mount Cook, and agreed to return Aoraki maunga to Ngāi Tahu. Ngāi Tahu would then gift the maunga to the people of New Zealand while retaining an active and ongoing role in the management of the area.[4]

On 29 September 1998, the New Zealand Parliament passed the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998. The Act enshrined in law the agreements recorded in the Ngāi Tahu Deed of Settlement and activated the settlement redress package. On 29 November 1998, Prime Minister Jenny Shipley delivered the Crown apology to Ngāi Tahu gathered at Ōnuku Marae on Banks Peninsula.

More than a decade earlier, Tipene O’Regan had addressed the Waitangi Tribunal on the traditional history and identity of Ngāi Tahu whānui. For generations of Ngāi Tahu, colonisation had more or less wiped their iwi off the map and out of the consciousness of most New Zealanders. Ngāi Tahu had suffered a perception that they were, in O’Regan’s words, “something less than Maori, as culturally impoverished.”[5] Amongst other things, the Ngāi Tahu settlement is significant for its contribution to turning that perception around.

After the settlement was finalised, Ngāi Tahu – in the words of some commentators – was “the whale that awoke”.[6] Today Ngāi Tahu are well-known as tangata whenua across most of Te Waipounamu. Ngāi Tahu institutions are strong, the iwi is empowered to exercise its kaitiaki responsibilities over the natural environment in a variety of ways, and Ngāi Tahutanga is flourishing. Ngāi Tahu commercial activities in farming, property, seafood and tourism are also booming. Last week Ngāi Tahu announced a net profit of $126.8 million for the year ending June 2017, and iwi Kaiwhakahaere Lisa Tumahai told Radio New Zealand that the iwi’s net worth had reached $1.36 billion.[7]

As well as the significances for Ngāi Tahu whānui, the Ngāi Tahu Deed of Settlement has served as an influential model for subsequent Treaty settlements. Following on from the Ngāi Tahu Deed and several other major agreements signed in the 1990s (the largest being the 1992 Fisheries Settlement and 1995 Waikato Raupatu Settlement), individual iwi and the Crown have completed a steadily increasing number of deals in the twenty-first century. As at 17 August 2017, the Crown had signed 85 deeds of settlement with different iwi.[8]

Understanding the Ngāi Tahu claims and settlement

The Ngāi Tahu Deed of Settlement was the product of lengthy direct negotiations between Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and the Crown. But the history of Te Kerēme is much much longer. Here at the Hocken Collections we are privileged to care for a wealth of material that illuminates Ngāi Tahu history and culture. Through He Kī Taurangi, the Memorandum of Understanding between Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and the University of Otago, we maintain a special relationship with Ngāi Tahu. For an overview of Ngāi Tahu material at the Hocken you can download our reference guide to Kāi Tahu Sources at the Hocken Collections. The collections contain many sources that can help us to understand Te Kerēme and its history, to understand the settlement itself, and to contextualise and critique the settlement.

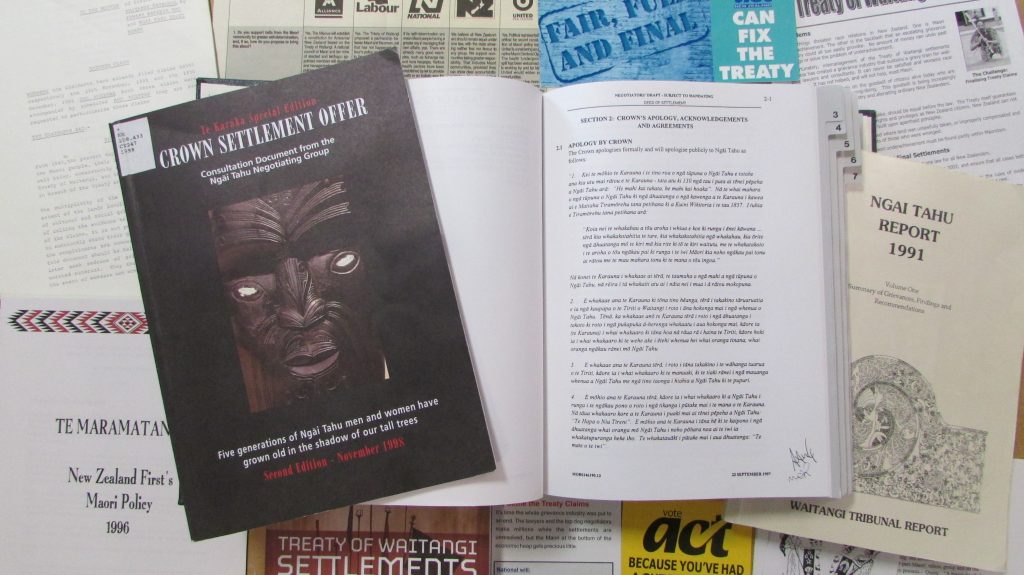

Jumping straight to the more recent history of Te Kerēme, it is important to understand that the settlement negotiations followed an extensive period of Waitangi Tribunal inquiries into Ngāi Tahu grievances. The Waitangi Tribunal began investigating Te Kerēme in the late-1980s and presented its findings and recommendations in several substantial reports published in the early-1990s.

A selection of resources on the Ngāi Tahu settlement at the Hocken Collections

In addition to the Waitangi Tribunal’s published reports, the Hocken holds two large archival collections of evidence presented to the Tribunal by the Ngāi Tahu Māori Trust Board and the Crown. With a combined total of more than 700 items, these are rich collections. As well as legal submissions they contain whakapapa, traditional histories, maps, plans and research reports on a wide variety of topics. Did you know the Crown promised to reserve land for Ngāi Tahu on Princes Street as a place to land waka? What ever happened to that? Only one way to find out…

Hocken’s published collections contain the Tribunal’s reports, the Deed of Settlement, and further items that provide insights into the settlement negotiations and the significance of the settlement itself. In addition to government briefings, iwi consultation documents and other publications directly related to the settlement negotiations, we hold many books, theses, journals and newspapers that address and analyse the Ngāi Tahu settlement and the wider processes of claims inquiries and negotiated settlements. “Are Treaty of Waitangi settlements achieving justice?” you might be asking yourself. If so, you will be glad to know that we hold a PhD thesis with a particular focus on the Ngāi Tahu settlement that addresses that very question.

Hocken’s collection of New Zealand election ephemera is another important resource for researchers seeking to understand the ways in which Treaty of Waitangi claims and settlements were represented in the wider political discussion at the time of the Ngāi Tahu settlement. Hocken Collections Assistants recently completed a project to list all items in the Hocken election ephemera collection, a collection that encompasses electioneering material dating from the beginning of the twentieth century right up to the present. The project team was struck by the frequency with which Treaty of Waitangi issues featured in electioneering material received from a broad range of candidates and parties, particularly from the 1996 and 1999 general elections. These items help paint a picture of both the importance and the controversy that was attached to deals like the Ngāi Tahu settlement at a time when Treaty settlements were a new frontier in the New Zealand political landscape.

Want to learn more? Come in and see us at the Hocken Collections. We are open Monday to Saturday, from 10am to 5pm.

For those of you that cannot visit the Hocken Collections in person, you can learn a little more about Te Kerēme and the Ngāi Tahu Treaty settlement by visiting these websites:

- http://ngaitahu.iwi.nz/ngai-tahu/the-settlement/claim-history/

- http://www.treaty2u.govt.nz/the-treaty-Today/the-ngai-tahu-claim/index.htm

For more information about historical Treaty of Waitangi claims and Treaty of Waitangi settlements, check out the websites of the Waitangi Tribunal and the Office of Treaty Settlements.

[1] “Ngāi Tahu” is used in this post for consistency with the iwi name used in the documents generated by the Waitangi Tribunal and Treaty settlement processes. However, “Kāi Tahu” is commonly used in the regions south of the Waitaki River.

[2] You can read the full text of the Crown’s apology to Ngāi Tahu (as it appeared in the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998) in te reo Māori here, and in English here.

[3] Parties Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and Her Majesty the Queen in right of New Zealand: Deed of Settlement, (Wellington: Office of the Minister in Charge of Treaty of Waitangi Negotiations, 1997), section 2.3.1.

[4] “Aoraki,” Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu website: http://ngaitahu.iwi.nz/ngai-tahu/the-settlement/settlement-offer/aoraki/ (accessed 20 November 2017).

[5] “Brief of evidence: Tipene O’Regan: Ka korero o mua o Kaitahu whanui,” (Wai 27, #A27).

[6] Ann Parsonson, “Ngāi Tahu – The Whale That Awoke: From Claim to Settlement (1960-1998),” in John Cookson and Graeme Dunstall (eds), Southern Capital – Christchurch – Towards a City Biography 1850-2000, (Christchurch: Canterbury University Press, 2000), p. 272.

[7] “Ngāi Tahu announces $1.26m annual profit,” Radio New Zealand website, 15 November 2017: https://www.radionz.co.nz/news/te-manu-korihi/343912/ngai-tahu-announces-126-point-8m-annual-profit (accessed 17 November 2017).

[8] “Deed of Settlement signed with Ngāti Hei,” Beehive.govt.nz website, 17 August 2017: https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/deed-settlement-signed-ng%C4%81ti-hei (accessed 17 November 2017).