Tēnā koutou katoa, ko Scarlett Rogers tōku ingoa, nō Ōtepoti ahau.

I am currently a student at the University of Otago and am doing my last paper to complete my Bachelor of Applied Science with a double major in History and Physical Education, Activity and Health. I have a passion for both the history of Aotearoa and the outdoors, hence the combination of art and science within my degree.

This summer (2022-2023) I was lucky enough to receive a scholarship from the Centre for Research on Colonial Culture (CRoCC), and Uare Taoka o Hākena Hockens Collections welcomed me as part of their team to carry out research. I was assigned to work with the Pictorial Department where I helped the Hocken Librarian with a publication that was being prepared in conjunction with an upcoming exhibition. This project is a collaboration between Uare Taoka o Hākena Hocken Collections, Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum, and Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand. When I was told I would be helping with a publication that involved all three of the above institutions, I felt like I had landed on a gold mine. This internship very quickly became a once in a lifetime opportunity, especially for me as a student in the History department, who is very interested in both history and writing.

My role within this project was to research and write a chronology from 1840 to 1899 that captured the rapid changes in photographic technology as well as society in Aotearoa in this period. Another focus was to approach the chronology from a Te Ao Māori lens. This aspect of the research was particularly important as it tied into the research CroCC covers. I was also assigned to write a glossary that focused on the key photographic terms covered in the book. Another aspect of my role was to attend the publication meetings and take minutes. These meetings were eye-opening because they gave me a sneak peek into the world of publishing. It was great to listen in on the creative conversations and see the complexities involved, particularly with a book that has multiple authors and institutions involved.

The book’s purpose is to highlight the extensive photographic collections that each institution has, as well as to complement the exhibition that will eventually be on display at each institution. The book’s target audience is diverse, but one objective was to write it at a level that secondary pupils could easily understand. It is hoped that the new New Zealand Aotearoa Histories Curriculum will make use of this book as a resource. The chronology is included in the book to give anyone who is reading it a broad understanding of photography at the time, but it will be especially useful for students who might want to focus on one event or a particular period.

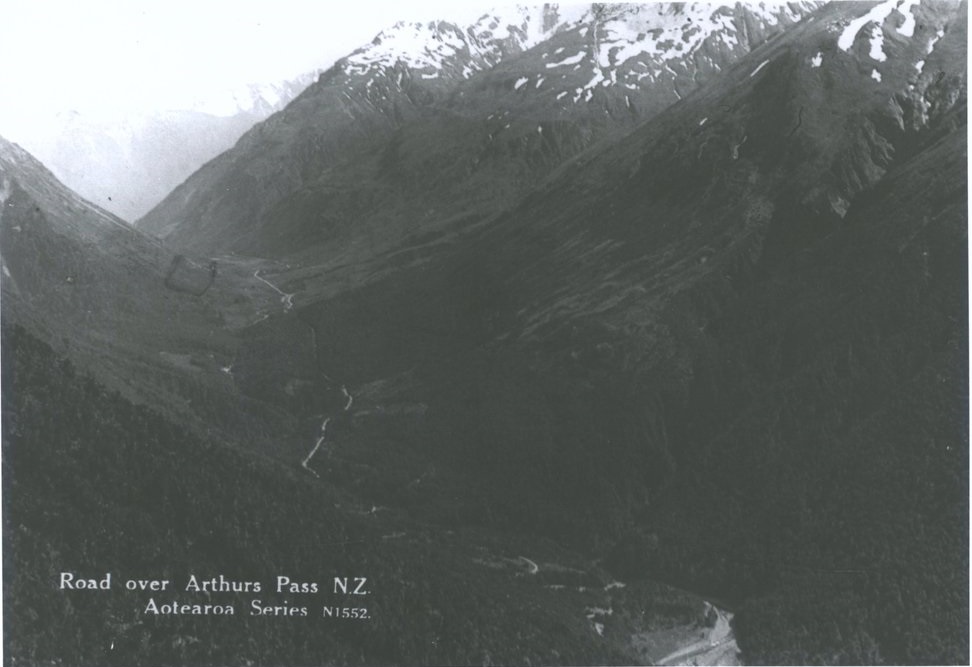

The timeframe that the publication focuses on is significant in many ways because the invention of photography closely coincided with the colonisation of Aotearoa. This gives the history of photography in Aotearoa a special quality as it captured the raw nature of the very new colony. One important point that unfolded while I was researching was that photographs from that period were taken by Pākehā settlers or explorers. For example, in 1865 the construction of Arthurs Pass was photographed in detail which illuminates the significance of the road for settlers. But what these photographs do not capture is how Māori felt about the whenua being carved up and trees being cut down for the industrialisation of the country.

Road over Arthur’s Pass, NZ. Aotearoa Series no N1552. Hocken Collections

This highlights how photography was yet another tool of colonisation. Although many Māori were in photographs there were no known Māori photographers during this period. This signifies how photography at the time might be used as a tool of privilege and control. Pākehā with access to cameras had the autonomy to choose what they deemed worthy of being photographed. When analysing photographs from this period it is important to consider the narrative being told and to remember that the images have been captured and curated by colonial settler society.

Although Māori were not behind the camera they were consumers of photography. Māori incorporated this Western technology into their own culture by displaying photography in their marae. Māori viewed photographs of whānau as much more than just tangible keepsakes and understood photographs of loved ones to hold mauri (life force). Photographs such as these became especially valuable after the person in the image had died.

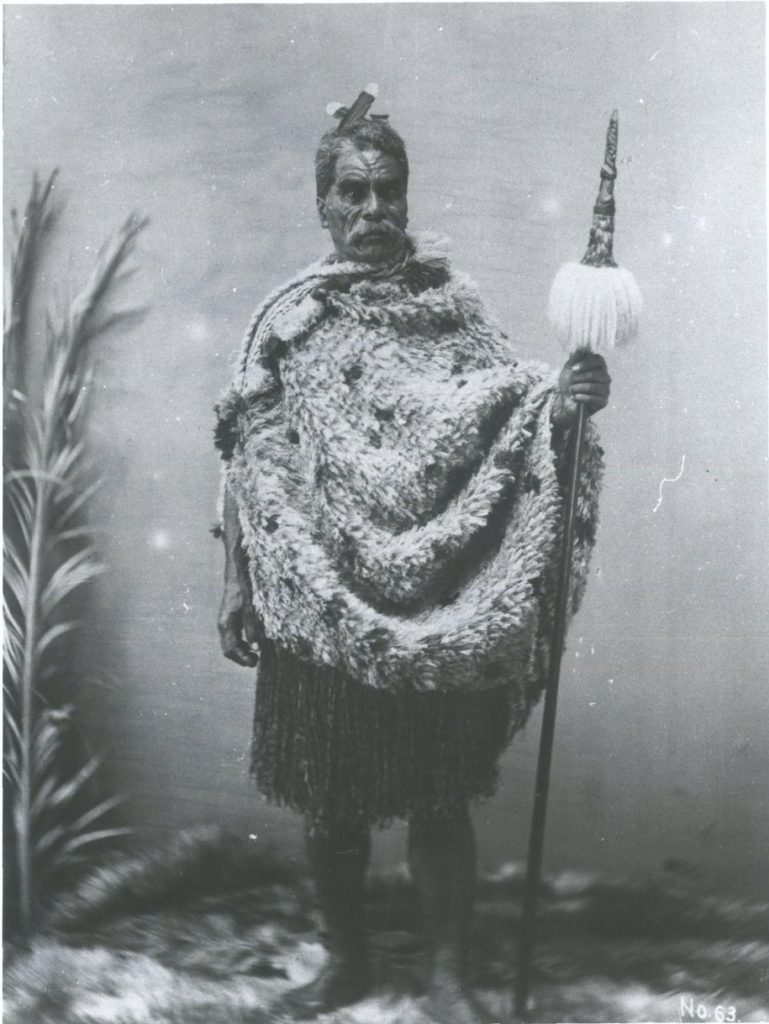

I found it interesting that by 1860 traditional Māori dress was only worn on special occasions in Aotearoa; portrait sessions often being significant enough. The tradition of men being adorned with moko had also decreased. But images were often retouched and moko were drawn onto Māori after the photograph had been taken; perhaps to inject the indigenous back into the subject. There was a high demand for photographs of Māori because of the popularity of the images overseas. It was eye-opening to find out how widespread early photographs of Māori were around the world. This led me to ponder the ethics around this and question who had the right of ownership over these photographs: the photographer, or the subject?

Maori chief with taiaha (c.1900), photographer William A. Collis, Box-112-010, Hocken Collections

I had never utilised photography as historical evidence before, but after just a bit of research, I quickly became interested in photography and the way photographs can be used as historical evidence to comprehend a particular society. Through this project, I came to realise photographs often tell a story that simply can not be put into words. But on the flip side, it is easy to make assumptions about a photograph – which can be interpreted in so many different ways – which is why it is often valuable to use photographs alongside other evidence.

This internship bought up many questions which I would love to explore in future research and has also sparked my interest in photography. My mind has also been opened to the many different sources and forms of evidence that can be used for historical research. I had a lot of enlightening conversations while working in the Pictorial Department, and I got to see Hocken’s art collection for the first time. I had been on many tours in the downstairs stacks at the Hocken before, but I was amazed to see the extensive art and photography collections in the upstairs spaces at the Hocken Library. My time as a CroCC intern proved to be tremendously informative and interesting because before I started I knew very little about the subject of photography or how the Hocken operated. I have learnt a lot about how to analyse photography in the context of historiography and as a by-product, I have learnt more about the history of Aotearoa.