Post researched and written by Jennie Henderson, Hocken Collections Assistant – Publications

As a researcher, the promise of what might be hiding in a primary source can be irresistible. Primary sources can convey a sense of time, place, and personality like nothing else. There is a great satisfaction that comes from connecting the dots between sources and watching a narrative rise up from your research.

Recently, some staff members at the Hocken were invited to take part in a research project. The aim? To hone our research skills and to learn about topics and sources that were unfamiliar to us. My chosen topic was ‘Surveyors and surveying’ – an area with a massive range of possibilities.[1] After I had spent some time floundering about in the worthy deeds of New Zealand’s pioneer surveyors, one of our knowledgeable archivists pointed me towards the John Reid and Sons collection.

In the 1870s and 1880s, when suburban growth in Dunedin was expanding rapidly, surveying and civil engineering firms flourished. One such firm was Reid and Duncans, established in 1876 by engineer George Smith Duncan, his brother James Duncan, and John Reid. Reid was a farmer and storekeeper who had also worked as a draughtsman under John Turnbull Thomson in the Survey Department in Dunedin. G.S. Duncan had trained as an engineer, and worked for another Dunedin firm before going into partnership with his brother and Reid. Duncan was particularly well-known for his work on the Roslyn and Mornington cable tramways. The Duncan brothers moved to Melbourne to work for the Melbourne Tramway Trust in the mid-1880s, and John Reid’s son Henry William Reid joined the company in their place. The firm changed its name to John Reid and Son, and when Edward Herbert Reid joined the firm three years later it became John Reid and Sons.[2]

Their collection (ARC-0704) is a mixture of business records – contracts, diaries, plans, and correspondence – some of which were purchased at auction, and some of which were donated. Knowing nothing about the firm, I requested the first diary on the list: Diary of John Cunningham.[3]

Cunningham was a Dunedin-born surveyor who worked for Reid and Duncans in the early 1880s. His diaries provide the bare bones of his day-to-day work: ‘In office took parcel up for Mr Duncan to Roslyn’; ‘Wet in morning in office levelling in afternoon’; ‘cleaning theodolites’.[4] And in the early stages of my research I noticed (to my amusement) that Cunningham’s particular style of handwriting made his many references to a ‘wet day’ look like ‘wet dog’, as on 4 April 1879:

Diary of John Cunningham, MS-3801/002, John Reid and Sons Limited: Records (1873-1915, 1929-1930), ARC-0704, Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago.

Reading through his diaries gave me a sense of just how busy urban surveyors were – working on several jobs at a time, travelling considerable distances, juggling weather and the field/office requirements of their job. Cunningham refers to jobs in Opoho, Roslyn, Sawyers Bay, Otakia, Halfway Bush, Kaikorai, Blueskin, Glenleith, Princes Street, and Green Island. These men were often civil engineers and land and estate agents as well as surveyors.[5] They would not only survey blocks of land and the roads providing access to them, but work with the road boards and borough councils to select contractors for building the roads, and sell off the blocks of land they had subdivided for their clients.[6] Their work was checked for accuracy by the Chief Surveyor’s office, who would not hesitate to send plans back if they did not meet the standard.[7]

Cunningham made many references to working on the Roslyn tram project, which reflects the importance of the project to the firm, and particularly to the Duncans. He often worked with John Reid and George Duncan (as well as other staff members) which suggests the company’s partners remained actively involved with the business, in the field as well as in the office. But it was Cunningham’s references to working at Littlebourne which particularly caught my eye. Littlebourne, that grand house which sits in a back corner of Dunedin’s memory – what would Cunningham’s diaries reveal about its past?

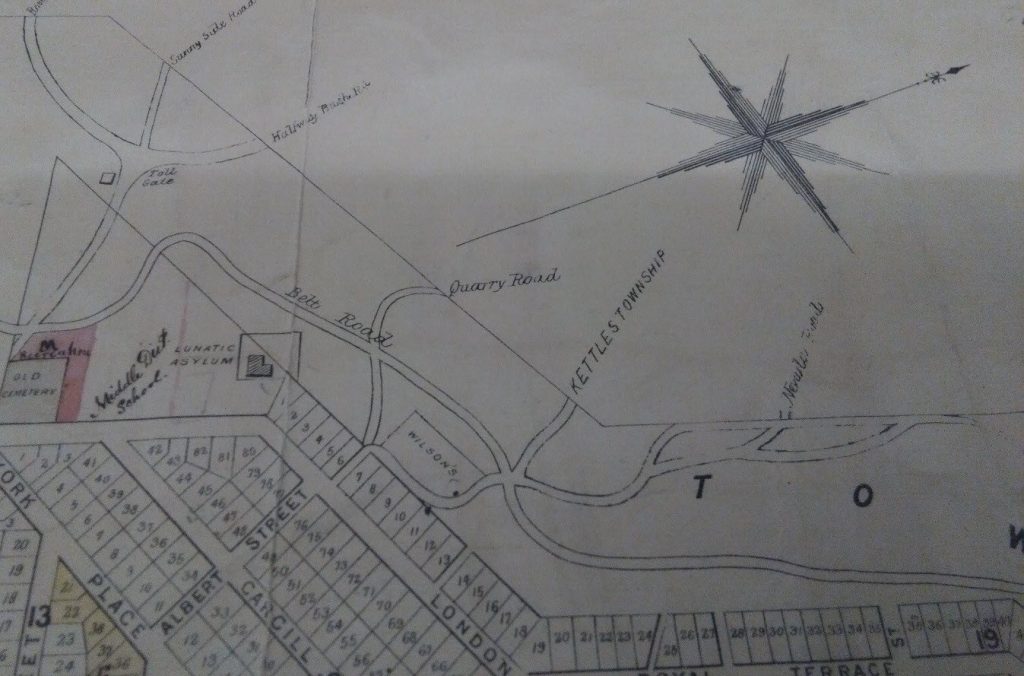

Littlebourne was the name Charles Kettle, Otago’s first Chief Surveyor, gave to his hand-picked 20 acre property: Sections 1 and 2, Block 1, Upper Kaikorai. On some early maps, this area is called ‘Kettle’s Township’.

Wise’s New Zealand Directory map of the City of Dunedin, N.Z, 1875, Dunedin: Henry Wise & Co, 1875. Hocken Maps Collection, Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago.

Kettle settled there in 1860 and built a home on the land after several years of farming in South Otago. He died of typhoid in 1862, and parts of his estate were leased and sold off in the 1870s.[8] John Cunningham’s involvement began with the purchase of the property by local businessman J.M. Ritchie around 1880.[9] Ritchie planned to subdivide the land and engaged Reid and Duncans to survey the sections and mark out the roads. Cunningham’s first mention of working on the property is on 31 January, 1881. He refers to being in the field at Littlebourne, and ‘plotting and calculating Littlebourne’.[10] He mentions ‘...attending City Surveyor and Mayor to get there [sic] signatures attached to plan of Littlebourne’and ‘chaining ajoining [sic] boundarys [sic] to Littlebourne to see whether encroaching or not…’.[11] He also refers to taking levels for ‘Mr Ritchie’s propsed Township Moari [sic] Hill’, which suggests Ritchie had bought much more land in the area.[12]

The John Reid and Sons collection holds other diaries, and I was interested to see if I could match Cunningham’s experiences with the colleagues he mentions in his entries. Sure enough, A.J. Duncan’s diaries (George Smith Duncan’s younger brother Alfred John) are peppered with references to Kettle’s, Littlebourne, and Cunningham.[13] From the end of 1880, and right through into 1882, Duncan worked frequently at Littlebourne and in the Roslyn/Maori Hill area for Mr Ritchie: ‘Fine day. Up at Kettles with G.S.D. and J. Cunningham and J. Reid in the morning.’;[14] ‘Up at Kettle’s for about 2 hours’; ‘Up at Kettle’s (Littlebourne Estate) with J.C. and J.R. all day’; ‘At Littleburn estate all day with JR and JC. Finished today’.[15] Even when the bulk of the field work was done, there were plans to be made in the office: ‘Calculations connected with Littlebourne estate all day’; ‘Fixing up litho. of Littlebourne Estate 3 hours’; and regular trips back up to the site for smaller details: ‘Up at Littlebourne for 2 hours defining line for contractor for wall on [?] section.’[16] Like Cunningham, Duncan also refers to working for Mr Ritchie on other jobs in the area: ‘Up at survey for Mr Ritchie Bk VIII Upper Kaikoarai [sic], part of sects 1 2 3 half day’; ‘At Mr Ritchie’s survey (Maori Hill) all day’; ‘Finished sketch plan to day and handed it to Mr Ritchie’s (2 hours).[17]

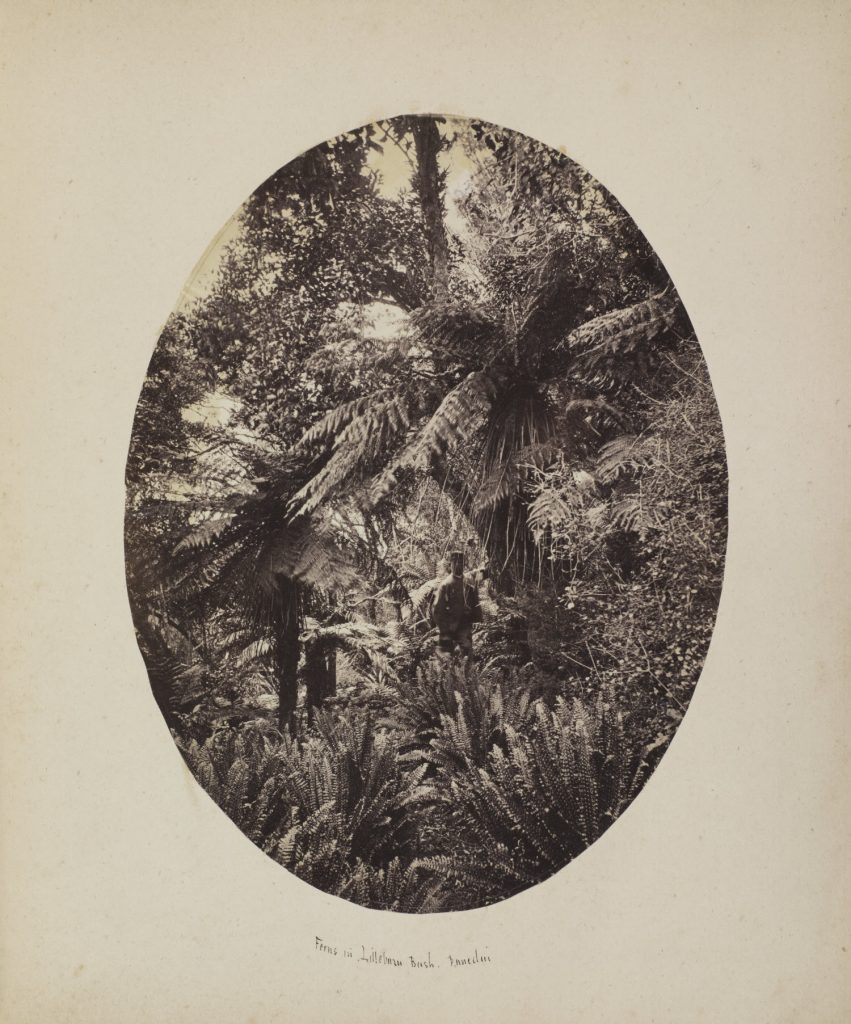

Slowly, a narrative was beginning to form: of urban surveyors working six days a week to meet the needs of an expanding city and its wealthiest citizens, of an area of town opening up to new construction, of the changing shape of Dunedin, of the influence of religious interest groups in deciding the layout of the town.[18] I wanted now to connect the dots of the human story underneath the blocks and sections as well, and helpfully the Hocken’s photograph collection provided an idea of what working on the Littlebourne site may have been like.

“Ferns in Littleburn Bush”, from album 114, W. M. Hodgkins “Dunedin & Otago”, page 09. Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago [S18-029a].

Could I flesh out Cunningham’s and Duncan’s personal stories even more? Would we have any of the Reid and Duncans material to which they contributed? Yes! In the John Reid and Sons collection are plans relating to ‘Littleburn Estate’ and ‘Township of Cannington’ (c.1881).[22] These plans show road levels for the subdivision. A.J. Duncan specifically mentions ‘working at plans of Road through Littleburn Estate’ and being ‘up at Littlebourne Estate taking levels of part of road.’[23] Finding the actual plans that Duncan referenced in his diary provided another layer of substance to the surveyors’ experiences, and brought me a delightful moment of connecting the dots.

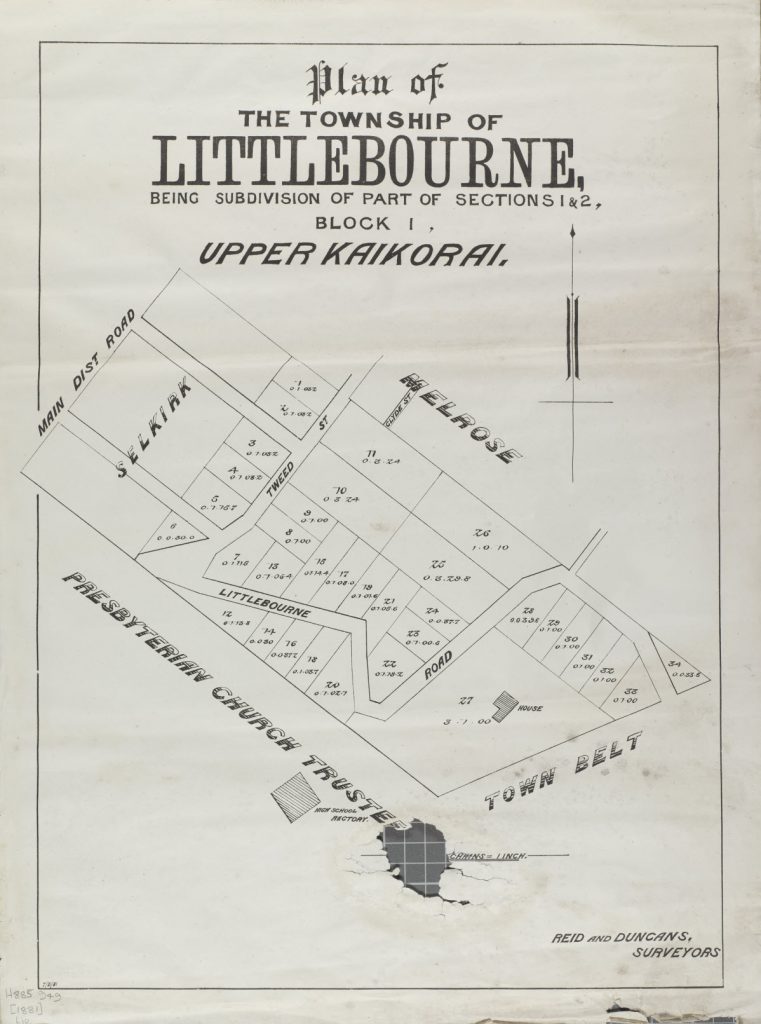

The Hocken Maps collection also held some treasures connected to the subdivision and the surveyors. Reid and Duncans’ finished ‘Plan of the Township of Littlebourne’ (1881) shows the Kettles’ house, and the Otago Boys High School Rectory.

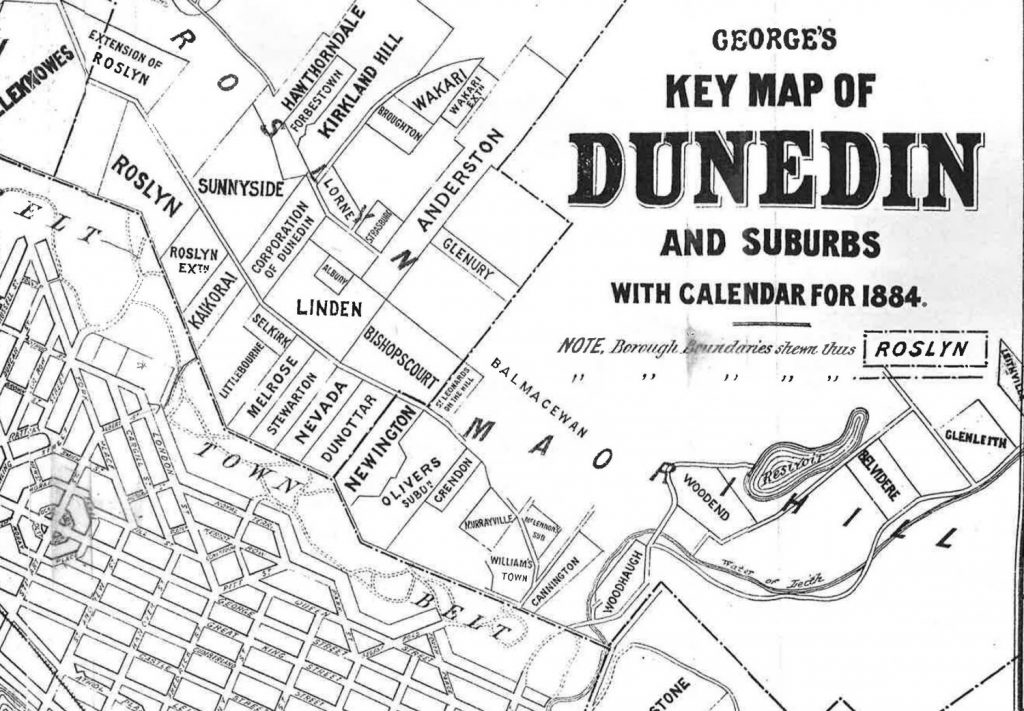

Plan of The Township of Littlebourne: being subdivision of part 09 sections 1 & 2, Block 1, Upper Kaikorai. Reid & Duncan, Surveyors Hocken Maps Collection Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago [S18-519a] (For interest, compare this to George’s Key Map of Dunedin and suburbs with calendar for 1884, where the different parts of the subdivision and the eventual route of the extension of Stuart St through Albert St and up to Highgate can be clearly seen.[24])

Detail of George’s key map of Dunedin and Suburbs with calendar for 1884, Dunedin, Thos. George, 1884. Hocken Maps Collection; Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago.

Another copy of this plan was used to advertise the sale of the subdivided sections in 1881, and Papers Past provides details of the auction and the buyers.[25] Successful businessman John Roberts, previously affirmed as a part-owner in 1874, purchased the house and section for £2700. Roberts had married Kettle’s daughter Louisa in 1870. Together, they built the world-famous-in-Dunedin Littlebourne House in 1890. Their mansion, gifted to Dunedin City after Roberts’ death in 1934, was demolished in 1949 to make room for the Stuart Street extension, and the remaining land made into sportsfields (just above Moana Pool).[26]

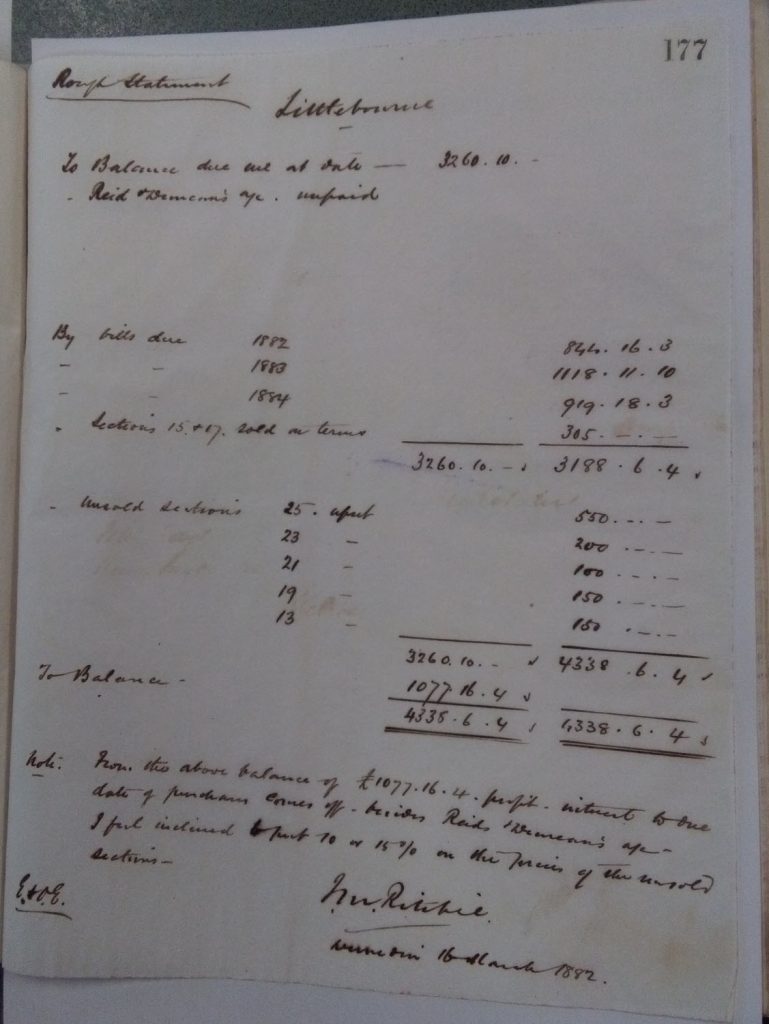

We can also flesh out our Littlebourne surveying story by taking a little time for J.M.Ritchie. At the time of his purchase of the Littlebourne block, Ritchie was a managing director of the National Mortgage and Agency Company of New Zealand (N.M.A.). He was known as an astute and successful businessman, owning rural land worth £29,000 and urban land worth £9,000, which goes some way to explaining how he could finance such extensive land purchases and development.[27] The Hocken holds the N.M.A. records in a restricted collection, in which some of Ritchie’s private letter books are included.[28] Ritchie’s Cannington Estate Letter Book 1877-1885 provided several connect-the-dots moments with its frequent references to Littlebourne, including to Park and Bradshaw (buyers of sections 16 and 28 respectively in the auction). It made me smile to find, in the letter book, Ritchie’s 1882 ‘Rough Statement’ which included an unpaid account to Reid and Duncans – beautifully concrete evidence of their relationship in this business endeavour.[29]

Cannington Estate Letter Book 1877-1885, N.M.A. Company of New Zealand Limited : Records (c.1861-1960), Box 6, UN-028, Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago.

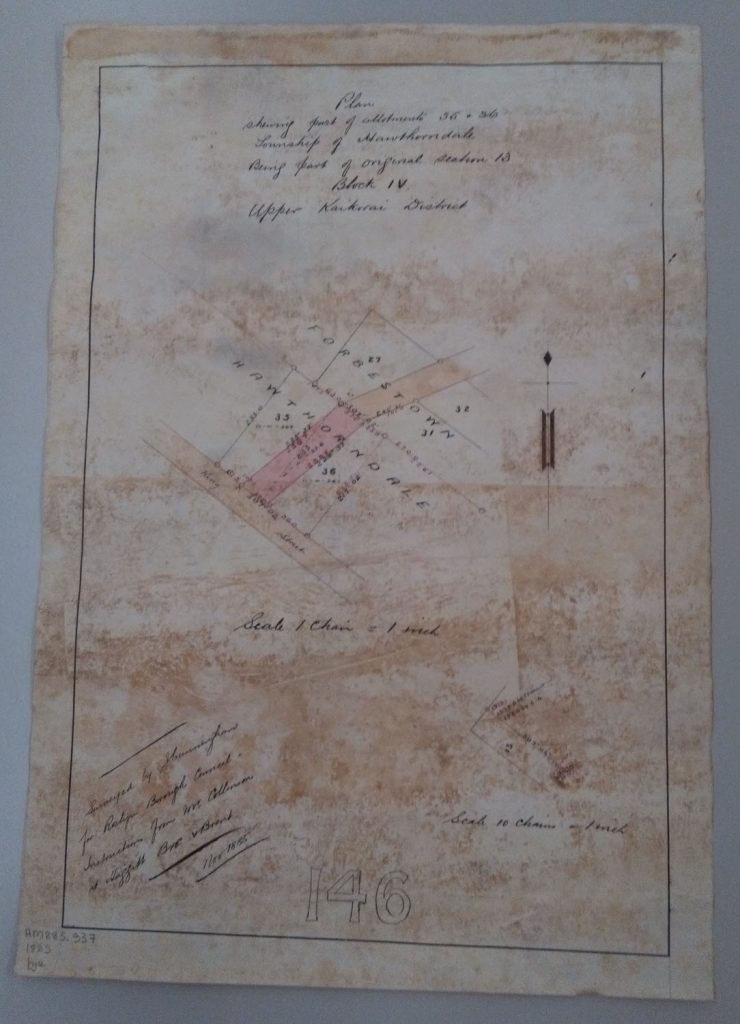

And what of John Cunningham? It seems that he may have left Reid and Duncans soon after, because in the Stone’s Trade Directory for 1884, he is listed as an independent surveyor. Hocken Collections holds some maps attributed to him alone, the earliest being from 1885:

Plan shewing part of allotments 35 & 36, township of Hawthorndale, being part of original section 13, Block IV, Upper Kaikorai District, surveyed by J. Cunningham for Roslyn Borough Council. Instruction from Mr. Collinson at Haggitt Bro’s & Brent, Nov. 1885. Hocken Maps Collection. Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago.

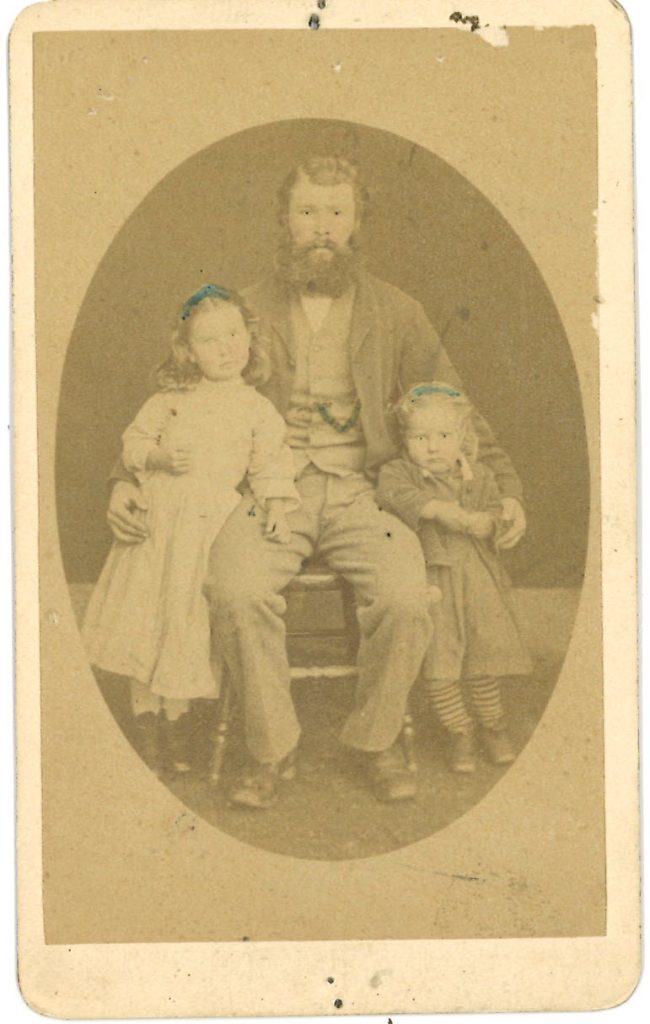

I took particular joy in seeing Cunningham’s writing and hand-drawn plan here, especially as my research began with his references to a ‘wet dog’.[30] John had married Elizabeth McKay in 1880, and they had five children. He and his wife lived in the Wakari/Halfway Bush area for the rest of his life, and are buried together in Andersons Bay cemetery. In the course of falling down a genealogical rabbit hole at the very end of my research, I found this photo of him on Ancestry. The girl is simply named ‘Betty’, and I wonder if it was John’s granddaughter Mary Elizabeth Thomson (1919-2014).

John Cunningham with Betty, posted by mtate76 in the Furneaux family tree on Ancestry, accessed 1 March 2019. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com.au/family-tree/person/tree/17373132/person/28043342587/Gallery?_phtarg=yNA12

One of the biggest challenges with researching primary material is when to stop. There is always further digging to be done, and it feels as if the connection you are seeking could be just over the page. The matters touched on above would benefit from further investigation in the land records, contemporary newspapers, biographical details of the people involved, looking into the Road Boards and Roslyn/Maori Hill Borough Council Records, and of course, more trawling through Papers Past. There are also many more employee diaries in the John Reid and Sons archives, and plenty of scope for research into their work on Dunedin’s tramways. From the people perspective, there are many more personal stories to be told from these sources.

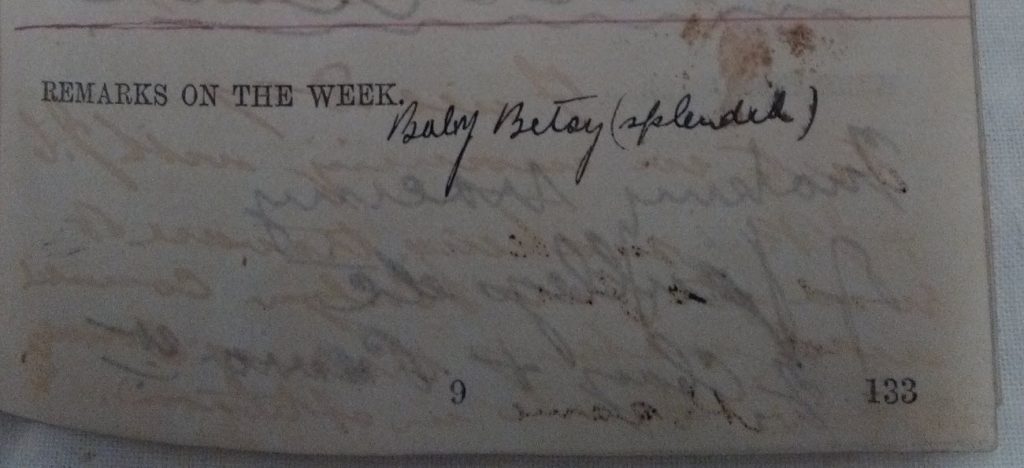

The unfinished lead from this research that has stayed with me the most is a reference from A.J. Duncan in November 1880. In the section of the diary that is used for ‘Remarks on the week’, Duncan wrote ‘Baby Betsy, splendid.’ It was the only truly personal reference in his diaries, and I felt certain that he was referring to the birth of a daughter, or perhaps the daughter of one of his 14(!) brothers and sisters. But after spending more time than I really ought to have tracking down his family members on genealogical sites, it seems unlikely that Betsy was a relative, unless he was referring to his sister Isabella’s daughter, Elsie Barbara (could her nickname have been Betsy?), who would have been turning one soon after that entry was made. Nor did John Cunningham have a daughter Betsy or Elizabeth. Perhaps Betsy was the daughter of another colleague whose diary I did not get to. But from this final piece of research I have had a taste of what draws genealogists back, again and again, to find their people: – the essence of past lives lived must be there, just around the corner, if only the researcher can pin it down. And that is the charm of primary sources: they promise to illuminate the human experiences beneath the ‘facts’ of history, if only the researcher is canny and determined enough to find them.

Diary of A.J. Duncan (1880), November 1880, MS-3801/004, John Reid and Sons Limited: Records (1873-1915, 1929-1930), ARC-0704, Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago.

To uncover your own narratives, join us at the Hocken Collections, Monday to Saturday, 10am-5pm (Pictorial Collections open Monday-Friday, 1pm-4pm). Our staff members are impressive repositories of knowledge in their own right. Please feel free to ask for assistance or guidance.

[1] To save the researcher some time, brief biographies of 450 early surveyors can be found in Charles Lawn, The Pioneer Land Surveyors of New Zealand (Wellington: New Zealand Institute of Surveyors, 1977). Published more recently, Janet Holm’s Caught Mapping: the life and times of New Zealand early surveyors (Christchurch: Hazard Press, 2005) is another excellent source on the challenges of surveying New Zealand in the earliest days of Pākehā settlement. In September 1994, the Friends of the Hocken Collections published an extensive bibliography of the Hocken’s surveying sources as part of their regular bulletin. See Welcome to the Hocken: Friends of the Hocken Collections—bulletin (Dunedin, 1991), September 1994.

[2] ‘George Smith Duncan’, in Jane Thomson, ed., Southern People: a dictionary of Otago Southland biography (Dunedin: Longacre Press, 1998), 141; ‘John Reid and Sons’, The Cyclopedia of New Zealand (Wellington: Cyclopedia, Co., 1897) 275-6.

[3] Diary of John Cunningham (1879), (1881), (1882), MS-3801/001-003, John Reid and Sons Limited: Records (1873-1915, 1929-1930), ARC-0704, Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago.

[4] Diary of John Cunningham (1879), 9 January 1879; 3 June 1879; 13 August 1879.

[5] Stone’s Directory for 1884 lists eleven civil engineers/civil engineering firms in Dunedin (including George S. Duncan of Reid and Duncans), and 32 surveyors. Ten of the individual surveyors were also listed as civil engineers. Four of the commission / estate agent firms listed also employed surveyors.

[6] For example, see the letter from the Maori Hill Town Clerk in a Reid and Duncans Inward Letter Book discussing the offer to form and metal roads in Sections I, II, III, Block VIII, Upper Kaikorai. Letters in this book are addressed to Reid and Duncan as ‘Engineers and Surveyors’ and ‘Land and Estate Agents’. Inward Letter Book (1879-1884), 2 February 1882 MS-3801/028, John Reid and Sons Limited, ARC-0704, Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago. See also Reid and Duncans’ call for tenders ‘for construction and metalling of streets through the Littlebourne Estate’, Otago Daily Times (Dunedin, New Zealand), 10 February 1881, 1. The tender was presumably won by road contractor James O’Connor, who, six weeks later, was advertising topsoil for sale from Littleburn Estate. Evening Star (Dunedin, New Zealand), 28 March 1881, 3.

[7] Inward Letter Book (1879-1884), 14 February 1882 MS-3801/028.

[8] There is more digging to be done in the Land Records on this matter, but in 1873, five 21-year leases on two-three acre sections were offered for auction. Otago Daily Times, 30 September 1873, 4. In 1874, Kettle’s widow Amelia, Edward Bowes Cargill, and John Roberts (husband of Kettle’s daughter, Louisa) applied to have their ownership confirmed under the Land Transfer Act of 1870. Otago Daily Times, 20 July 1874, 3. In 1875, an ad appeared in the paper offering a long lease of the house and 15 acres. Evening Star, 26 November 1875, 3. The property must have been bought eventually, as in 1878, Mr F. Wayne and three partners offered all or some of the property to the Anglican Church as a bishop’s residence or cathedral site ‘on the same terms as those on which they recently purchased it, viz., £400 per annum rental for three years from 1st March next, and £8000 purchase money on the 1st March 1881.’ Otago Witness (Dunedin, New Zealand), 2 March 1878, 4. Despite a report recommending the purchase, the proposal was voted down at a meeting of the members of the Church of England. Evening Star, 10 May 1878, 4.

[9] According to Neighbourhood guide: Melrose Street, Avon Street, 23-55 Littlebourne Road, 53 Garfield Avenue, 1-12 Wallace Street (Dunedin, 199?), 1, the Kettles retained around four acres when the property was sold to Ritchie. However, the long trail of newspaper advertisements offering the property for lease or rent, and an 1881 article regarding the sale of the subdivided Littlebourne sections show that the house and 3.5 acres were also for sale, and that John Roberts bought them at auction. See Otago Daily Times, 9 March 1881.

[10] Diary of John Cunningham (1881), 31 January 1881, 4 February 1881, 4 March 1881, MS-3801/002.

[11] Ibid., 23 May 1881, 25 May 1881.

[12] Ibid., 14 November 1881. Maori Hill had been proclaimed a borough in 1876, and Roslyn in 1877. Albert Green, ‘A necklace of jade: the Dunedin Town Belt 1848-1903 (M.A. thesis, University of Otago, 2003), 24.

[13] Duncan also refers to surveying the land for the Synagogue in Moray Place with J. Reid and J. Cunningham. Diary of A.J. Duncan (1880), MS-3801/004, 23 July 1880, John Reid and Sons Limited: Records (1873-1915, 1929-1930), ARC-0704, Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago.

[14] Ibid., 29 October 1880.

[15] Diary of A.J. Duncan (1881), MS-3801/005, 29 January 1881; 7 February 1881; 18 February 1881; 12 September 1881;

[16] Ibid., 28 February 1881; 8 March 1881; 12 September 1881.

[17] Ibid., 19-25 September 1881. Duncan also mentions working at a survey for Mrs Ritchie, although it seems this may have been at a property at Port Chalmers.

[18] While urban surveyors were instrumental in the growth and shape of the city, a substantial discussion of their role is noticeably missing from much of the dialogue about early surveying. As Ben Schrader notes, New Zealand’s urban landscape and the role of cities in our national development has been largely overlooked by New Zealand historians, who prefer to focus on the impact of rural lifestyles on the development of New Zealand’s national identity. See Ben Schrader, Big Smoke: New Zealand cities, 1840-1920 (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 2016), 15-20. One could argue the same bias affects the study of surveying: surveying the wild, untamed landscape has been considered a more valuable contribution to the colonisation of New Zealand than the surveying of spaces already under Pākehā control.

[19] Two other Littleburn images can be seen here on Hocken’s site for digitised images: Hocken Snapshop.

[20] Etching reproduced in Neighbourhood guide, 2.

[21] Otago Daily Times, 29 January 1881, 4.

[22] Plans relating to ‘Littleburn Estate’ and ‘Township of Cannington’ (c.1881) MS-3968/001, John Reid and Sons Limited: Records (1873-1915, 1929-1930), ARC-0704, Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago.

[23] Diary of A.J. Duncan (1881), 3 February 1881; 2 April 1881, MS-3801/005.

[24] The Stuart St extension was built in 1949, and was one of the reasons for the demolition of Roberts’ Littlebourne House.

[25] See plan of the Township of Littlebourne, being Subdivision of Part of Sections 1 & 2, Block I, Upper Kaikorai, Dunedin: McLandress, Hepburn & Co., c.1881, Hocken Maps Collection, Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago. Advertisements for the sale emphasising the quality of the area, the access roads, and the proximity of the Roslyn Tramway can be found in Otago Daily Times, 29 January 1881, 4; 3 March 1881, 4; 9 March 1881, 2. Following the sale, calls for tenders for the erection of villas, gentleman’s residences and tennis-lawns at Littlebourne appeared in the paper. See ODT, 2 May 1881; 20 April 1882; 29 August 1882.

[26] See Hocken Snapshop’s image of Littlebourne House here.

[27] Jim McAloon, ‘Ritchie, John Macfarlane’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1993. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/2r24/ritchie-john-mcfarlane (accessed 23 April 2018)

[28] N.M.A. Company of New Zealand Limited : Records (c.1861-1960), UN-028. Access to this collection requires the permission of the Fletcher Trust Archives, Wellington.

[29] Cannington Estate Letter Book 1877-1885, N.M.A. Company of New Zealand Limited: Records (c.1861-1960), Box 6, UN-028, Hocken Collections, University of Otago, Dunedin.

[30] See also Plan shewing subdivision of original section 23, Block IV, Upper Kaikorai District: the property of Presbyterian Church Trustees / John Cunningham, surveyor, Oct. 1887, Hocken Maps Collection, Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago. The land he surveyed in this map belonged to the Presbyterian Church Trust, whose land can be seen adjacent to the Littlebourne subdivision on the Reid and Duncans’ map. An 1874 amendment to The Presbyterian Church of Otago Lands Act, 1866, had made provision for the Presbyterian Church Trustees to sell Trust lands to the Crown and reinvest the proceeds for the Church’s benefit. The sale of Church Trust land was a factor in Dunedin’s increasing suburban spread in this period.