Night terrors: Counting loss in a global pandemic

A post written by Ellan Baker and Susan Wardell, based on an ANTH424 assignment on ‘visual images and the communication of suffering and evil’.

On March 19th 2020, social media and news sites were flooded with images of military trucks, moving the dead out of the overwhelmed small Italian city of Bergamo, for cremation elsewhere [i]. Europe had replaced China as a new epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Northern Italy is known for having small towns and tightly-knit communities, as well as for the beautiful scenery, cuisine and fashion which attract both domestic and international tourists iv. It was largely through travel and social interaction, that the new strain of coronavirus (named SARS-CoV-2) was spreading. Places like Bergamo, a city of just over 100,000 residents, had little time to prepare iii ii.

Picturing the scale of loss

One of the images from mainstream television (Sky News) showing Italian army trucks transporting the dead. Source: https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-italian-army-called-in-to-carry-away-corpses-as-citys-crematorium-is-overwhelmed-11959994

At the time that images of the crematory trucks were released, Italy was in an exponential climb in the number of cases. The number of deaths had now become a few hundred a day, despite best efforts of intervention and prevention. On March 19th, total fatalities had reached 3,405 and were still increasing vi.

As the pandemic spread, people all over the world took in this type of numerical information, to make sense of what was happening v . Rates of spread, death tolls, graphs and spreadsheets… these were forms of knowledge about the reality of Covid-19, which were also somewhat removed from acknowledgements of the level of human suffering it was creating, with every new case, and with every death of a unique human person that those numbers represented.

In this blog we discuss the ideas that images, as a different way of communicating suffering and loss, can help to rehumanise topics such as this. We argue they provide understanding of the scale of devastation in a different way than numbers do, and can be part of catalysing social change because of this.

Echoes of (an invisible) war

Perhaps the most highly circulated images of the trucks (left) carrying the deceased through Bergamo, came from a tweet by Guido Salvaneschi, a citizen of Bergamo vii.

Perhaps the most highly circulated images of the trucks (left) carrying the deceased through Bergamo, came from a tweet by Guido Salvaneschi, a citizen of Bergamo vii.

Tightly packed, the military-style trucks are moving in single file down the street. The arrangement of the trucks on the empty street has a ceremonial feel; dark colours, and a string of lights. The road is clearly in an everyday residential area, with a shop, carpark and green field visible alongside. But here it becomes a platform for procession vii.

The escort occurred at night – the image taken at 9:28pm – almost as if they needed to hide the moving of the dead, and shelter the living population vii. Was the suffering so great, that it could not be experienced during the day? Like the living, the day is sheltered from agony; maintaining its symbolic goodness, while night is reserved for pain.

In the photo there are many trucks, and within each truck, there are many bodies vii. The photo both is and isn’t about numbers. The impact of this photo is largely because the trucks are in fact innumerable, their line extends out both sides of the frame of the photograph. It asks us to recognise the scale of loss without making us, or letting us, count and quantify. It evokes the horror of scale, without relying on numbers. It makes an affective connection to the topic, without being explicit.

The image of a fleet of military trucks can’t help but raise the ghosts of war; historical echoes that will have different levels of feeling attached for different viewers, in different places. At very least, the string of large trucks connotes a high number of casualties, and yet there is a disjunct for the viewer, since absent from the still and tidy environment they move through is any evidence of danger or threat. The toll is being counted, truck by truck, but the enemy itself is a ghostly absence; an invisible virus, impossible to see or to conceptualise, except through its effects.

Watching from afar

At this time this photo was taken and posted, New Zealand and many other countries felt far from the ‘front line’. The need to take action here was not yet evident. So we watched the situation unfold through images like this, but even as we did, the virus exponentially spread once again, leaving tremendous amounts of uncertainty in its wake iii

The now-famous images of these trucks did not come, in the first instance, from scientists, journalists, or other authoritative communicators. Rather they appeared in the often informal domain of social media. The context of apartments opposite implies that this photo too is taken from an apartment window, looking down. The photographer is distant from the street, giving an even more heightened sense of risk or taboo in the scene below.

The juxtaposition of the sombre with the everyday (both in terms of the setting, the intimate framing of the photo, and its context on social media) makes looking at it all the more difficult.

Images of tragedy and horror often circulate well on the media – like this one, going viral, reaching around the world. Anthropologists Arthur and Joan Kleinman wrote about the circulation of images in the media in 1996, before the advent of social media, and yet they discussed many trends we could see continuing, and even increasing, today. They note, for example “viewers become overwhelmed” from a distance and come to have “moral fatigue, exhaustion of empathy, and political despair.” ix

Given the continuous flow of numbers and statistics, of images and video, through the news, this could well have been the case. Yet people seemed to want to look. Kleinman & Kleinman also discuss that despite their potential to overwhelm, images of suffering are often appealing because they leave the viewer asking questions ix.

The unending line of crematory trucks going beyond the photo’s borders shows the impact of the viruses devastation. But what questions does it ask? Are they questions that are answerable? Either way, they were questions that New Zealand did have to approach, as citizens, and as a nation, not long after Italy.

The human struggle

“Struggling to cope” vii the photo caption says. This is, on one level, a comment about institutional and systemic capacity to practically process so many dead – since these trucks were deployed for the purpose of relieving an already overloaded crematory system vii. But the phrase can also read as a marker of psychological overwhelm for those living through the experience.

The pain that the virus has caused is immense. Images of the COVID 19 pandemic re-humanise numerical information, by bringing Twitter users closer to the suffering of those who are grieving losses of loved ones. This can be contrasted to the insistent numerical broadcasting, which removes the emotional quality and the human context of information, and by itself, refuses to acknowledge the human lives behind them. As the quote often attributed to Stalin goes: “if only one man dies … that is a tragedy. If millions die, that’s only statistics.” x

Meanwhile, images have a variety of different ways of highlighting the specific, situated, and human meanings of these numbers. For example, the image below is of a blessing taking place by the service providers, to finalise the deceased person’s life, with dignity.

Photo of two men giving dignity to the dead, despite the large number of dead and the lack of family or friends of the loved one present. Source: Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/5e30a130-d62a-4c4c-a81f-b89f2448d9c8

This image, taken by Italian news photographer Piero Cruciatti, offers something different to the sense of scale of death and loss in Salvanechi’s image, in terms of communicating the impact of COVID-19. It reveals one part of the story behind each number, behind each body that the viewer understands to be concealed in those many military trucks. It shows the layers of human care and meaning invested into each of them; how the people closest to the suffering still muster the strength and urgency to undertake the enormous amount of cultural and physical work required to bring each person’s precious life to a close.

It shows, perhaps, the tragedy of the ‘one man’ rather than the thousands, and in doing so, it arguably brings a different kind of understanding of this event, than it does to contemplate the thousands.

Image and response

Paul Frosh, an academic writing about digital media, and specifically how people view and respond to the suffering of distant othersxi. One’s moral “response-ability”, he argues, is linked to the sensory mediums through which one is viewing and responding. People who viewing Salvanechi’s photo on Twitter, for example, had to choose how to respond, with their eyes, hands, and attention. Practically this could mean many things; clicking, commenting, sharing. More broadly, categories such as ‘witnessing’ explain what type of moral response these micro-actions may represent.

Images can broach both a geographical and emotional distance, and act as a testimony and a memorial in and of themselves, to human experience, and human suffering. In Salvanechi’s photo, and the photo by Piero Cruciatti, we are forced to consider the suffering that quickly can become incomprehensible and overwhelming vii– given a chance to hold our gaze, and to be witnesses to this horrible reality. And in doing so, to form a kind of momentary connection with other people’s life world’s that is void in the production of infographics and statistical data in journalism.

In addition, there are practical responses that can flow on from this deeper kind of acknowledgement. Read in full, the caption on Salvanechi’s candid night-time photograph has a clear intended purpose; asking for more serious adherence to policies of social isolation, as a tactic to slow the spread of COVID-19. Kleinman and Kleinman’s article acknowledges that images can become a social and symbolic commodity for igniting action and change ix.

When New Zealand’s time came, we also had to make choices about setting policy, and also following policy. About lockdowns and closures and social distancing, and other dramatic social changes. Who can say whether the things we had already witnessed overseas, through the lens and eyes of journalists and everyday citizens on social media, was part of shaping our response?

To conclude…

Whether directly affected or not, in this strange period of human history we have all become ‘online witnesses’ the the COVID19 pandemic. Many of us have absorbed large amounts of numerical and statistical information every day iii, vi. While this information provides easily absorbable overviews of the virus’ impact, it cannot contain or express the more human aspects of this moment in time. However, sprinkled throughout the media coverage, have been images that have also mapped the scope and scale of the pandemic, but in an entirely different way.

Images can hurt us, can wound us. They can also, at the same time, offer an embodied empathetic experience of the suffering of others.. Sometimes they can contribute to changes not only in how we understand the world, but the choices we make in response to it. The images of crematory trucks in Northern Italy expressed the large scale devastation of the virus, at a moment in which the whole world was watching, and deciding how to react. What we owe to these cannot be measured.

References

i National Post, 2020. COVID-19 Italy: Military fleet carries coffins of coronavirus victims out of overwhelmed town. [Online]

Available at: https://nationalpost.com/news/world/covid-19-italy-videos-show-military-fleet-transporting-coffins-of-coronavirus-victims-out-of-overwhelmed-town

[Accessed 09 April 2020].

ii Worldometer, 2020. Italy Population (LIVE). [Online]

Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/italy-population/

[Accessed 20 April 2020].

iii NZHerald, 2020. Covid 19 coronavirus: How virus overwhelmed Italy with almost 5000 deaths in a month. [Online]

Available at: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/world/news/article.cfm?c_id=2&objectid=12318768

[Accessed 20 April 2020].

iv Turismo Bergamo, 2020. Visit Bergamo: An Italian masterpiece. [Online]

Available at: https://www.visitbergamo.net/en/news/item/278/

[Accessed 21 April 2020].

v Knox, C., 2020. NZHerald. [Online]

Available at: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12322890

[Accessed 04 May 2020].

vi Worldometers.info, 2020. WORLD / COUNTRIES / ITALY. [Online]

Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/italy/

[Accessed 20 April 2020].

vii Salvaneschi, G., 2020. Twitter.com. [Online]

Available at: https://twitter.com/guidosalva/status/1240555847849312256

[Accessed 09 April 2020].

viii Clark, H., 2020. Missing In Action: the lack of a globally co-ordinated response to Covid-19. [Online]

Available at: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/coronavirus/120969978/missing-in-action-the-lack-of-a-globally-coordinated-response-to-covid19

[Accessed 04 May 2020].

ix Kleinman, A. a. K. J., 1996. The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times. Daedalus, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

x Stalin, J., 1947. A Single Death is a Tragedy; a Million Deaths is a Statistic. [Online]

Available at: https://quoteinvestigator.com/2010/05/21/death-statistic/

[Accessed 21 April 2020].

xi Frosh, P., 2016. The mouse,the screen and the Holocaust witness: Interface aesthetics and moral response. New Media and Society, 20(1), pp. 351-368.

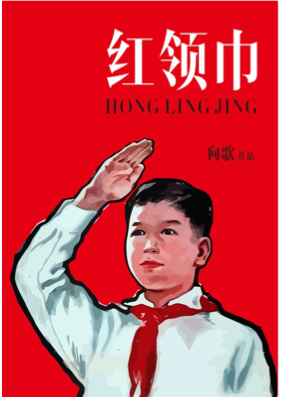

The Red Scarf: Obedience, Governance, and Bureaucracy in Chinese Primary Schools

Written by Yi Li, for an assignment on ‘administrative evil’ in ANTH424, edited and published with assistance from Dr Susan Wardell.

When I was almost six, at the beginning of primary school, my teacher told me: “You are not old enough to join the Young Pioneers.” I remember feeling depressed because this meant I could not wear a red scarf (Hong Ling Jin) until the following year. It meant that I would be separated from those marked as first-class pupils.

The Red Scarf as a symbol of youth glory

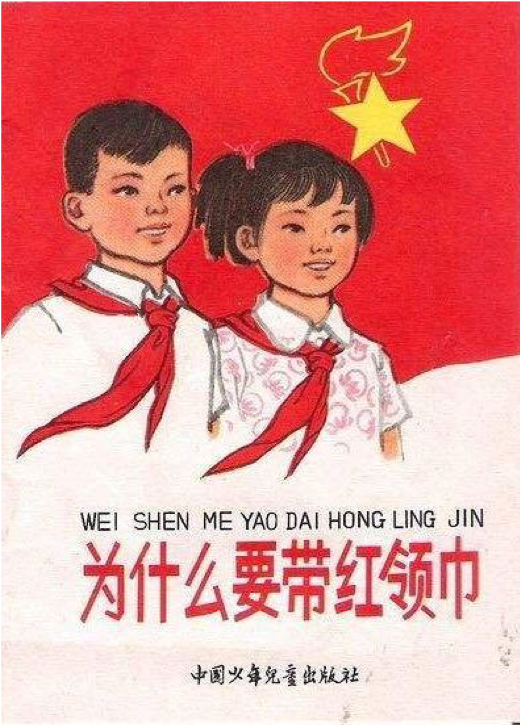

Figure 1: The Book Cover of ‘Why Wear a Red Scarf?’ Published by China Children’s Press, Photo from Google Images

In China, publications for children (as per Figure 1) and political education within the schooling system, jointly construct stories about how the Chinese martyrs and heroes’ blood dyed scarves red. Once the institutional power (of political and educational structures) authorised the narrative of ‘honour’ associated with these scarves, it was taken up as a political fashion among young people. However, only the most outstanding pupils – young people aged six to fourteen – were allowed to wear the red scarves issued by the government, as part of a movement called ‘Young Pioneers of China’. Similar movements successively appeared in many Communist countries, such as North Korea and the Soviet Republic.

The motto of the Young Pioneers of China is “To fight for the cause of communism: Be ready! Always being ready!”

This reflects the socialist construction of ‘red’ emotions, such as enthusiasm and selflessness. In turn this shows how ideology informs moral values and behaviours – forming a distinctly Chinese tradition (Kleinman and Kleinman, 1985, p. 473).

This is true even for my generation, who were born in peace-time. As children, we committed to follow the notion of the Young Pioneers: to be self-disciplined, and contribute to society. In doing so we took on forms of moral behaviour that were embedded in political systems.

In this blog post I argue the ‘administrative evil’ of Young Pioneers not only produces soft violence through formal and informal rule-making and punishments, but also generates social inequality. I also argue that the process creates a ‘shadow’ in adulthood, that I reflect on as being part of the social machinery of oppression as it functions in the collective childhood of Chinese students.

Establishing the Administration: inclusion and exclusion

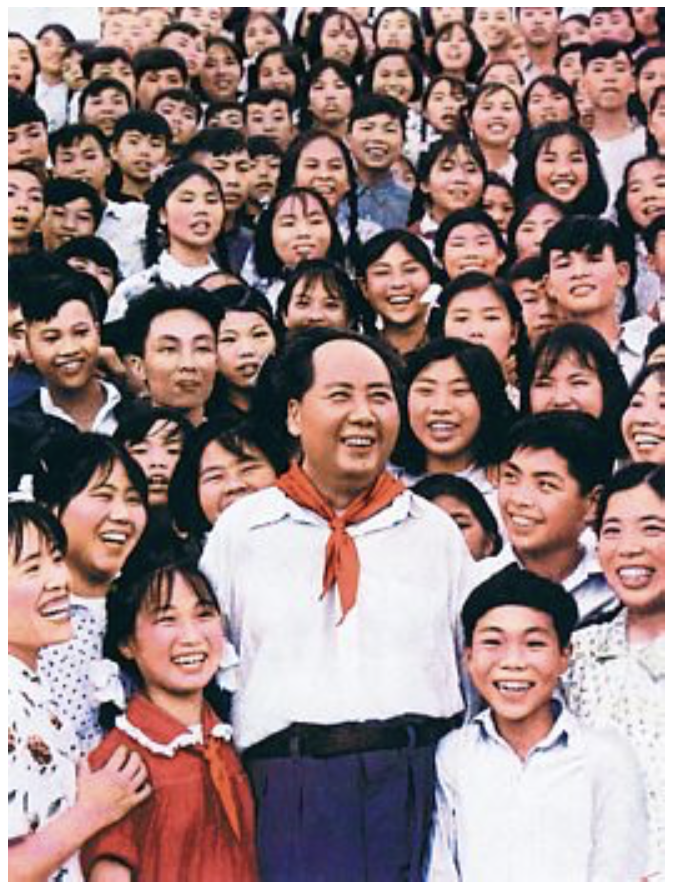

Figure 2: Young Pioneers Representative offered Red Scarf to Mao Zedong on 25th June 1959, in Mao’s hometown Shaoshan, Hunan province. (Photo from People.cn http://politics.people.com.cn/GB/1026/4792695.html)

In the middle of the 20th century (Figure 2), wearing a red scarf was the least privilege for very few authorised young pioneers. Two representatives (the boy and the girl next to Mao) were able to join first-class universities in Beijing once the government processed the resumption of college entrance examination in 1978. After graduation, they were expected to marry, because of this shared honour during childhood.

In contemporary primary schools (especially after the reform and opening-up policy in 1979), most pupils joined the Young Pioneers of China. To wear a red scarf on school days became everyone’s responsibility; for their class honour and individual dignity. Under the governance of senior pioneers, children’s obedience was cultivated by the ideological administration of youth glory.

Children who could not, or did not, join the young pioneers and wear red scarves became the minority among their peers (Figure 3). They would be excluded as outcasts for this. In this way, red scarves acted with authority, to include or exclude.

I vividly remember one day at school, when all my classmates shamed my desk-mate, for being the only person who had forgotten to wear the red scarf. A young ‘senior pioneer’ who was on duty deducted our class’ points, which led to us losing our status as ‘advanced’ level, in the final grade. My desk-mate was isolated by most classmates and mentors, for his accidental lapse. I remember that I remained silent, although I thought their behaviour toward him was wrong. Three months later, his father decided to transfer him to another school.

In this case, ordinary people like youth pioneers act appropriately to their organisational obligations, doing what those around them would agree they should be doing. Yet they participated in, or contributed to, what a critical and reasonable external observer might identify as morally wrong, in the distress they inflicted upon that one child.

What is administrative evil?

Social scientists Adams and Balfour (1998) deem that the technical-rational approach to social and political problems that characterises the modern age, has enabled a new and frightening form of evil. This evil is associated not with sadistic intention, but with harm caused by participation in the administration of everyday systems (Adams and Balfour, 1998, p. 13). Typically, and unlike many other forms of ethical failure, the appearance of ‘administrative evil’ is masked (Adams and Balfour, 1998). People can engage in acts of evil, unaware that they are doing so (Balfour and Alibašić, 2016).

Figure 3: Xi Jinping celebrated International Children’s Festival with Young Pioneers in Beijing Ethnicity Primary School on the 30th May 2014 (Credited by Xinhuanet, Photo from CCTV News http://news.cctv.com/2018/06/01/ARTISXoZr80oKgiYmjswGq3F180601.shtml)

As a child, I regarded the red scarf as the symbol of glory, as I was taught to do. But through this lens, as a scholar of anthropology now, I realise that it was a tool through which the children could enact and reinforce everyday systems of power, through bureaucratic systems within schools. In the harm it enacted on some children, it fits very closely with Adams and Balfour’s description of administrative evil.

Anthropologist Caton (2010, p.167) uses two philosophical concepts to unpack the idea of guilt or culpability in acts of evil: intentionality and contingency. These ideas highlight the way an anthropological analysis of evil should note the roots and contexts of actions; the role of both self-awareness (or lack thereof), and circumstance. In a similar way, Farmer (2004) proposes that anthropology of structural violence can often be understood as patterned by history, biology, and political economy (Farmer, 2004, p. 308), as well as individual ‘choice’.

Both of these views call for a holistic understanding of evil: linking macro forces to personal experience. Employing these theories is useful to examine the formation and social effect of Youth Pioneers movement, as an example of administrative power. In doing this I have also noted the rising collective nostalgia associated with red scarves, across now-adult populations.

The price of growth: collective nostalgia

In different historical contexts, both generations before and after the 1979 reform have been educated by the ideology of the red scarf – with wearing red scarves part of the recognition of excellence. When National leaders meet children who are honourees of the Young Pioneer programme, they do so knowing this glorious moment will be remembered (by the children, and others) as part of the chid’s lifelong glory.

For some individuals though, being deprived of the red scarf as a punishment has also become a part of the collective memory of a Chinese childhood.

Interestingly two different recent short films – Hong Ling Jin (2011) and The Red (2010) – both tell a story about boys were punished by confiscating their red scarves because they read cartoon books in classes. Under the punishment of the Young Pioneers, and under the institutions’ supervision, these actions cause the protagonists to fall into rebellion and self-doubt.

Both of the film’s directors were born in 1980s’ China. They described their creations as part of “nostalgia”, representing their experience in primary schools.

The social media response to these films reflects a recognition that the heart-breaking moment of losing a red scarf has formed a deeply emotional part of Chinese people’s individual and collective identity. However other aspects of public discussion on social media tends to interpret their films as the “indictment of red scarves”.

Onwards

The red scarf, a symbol accompanied by a legend about political heroes, presents a vision of glory to Chinese children. Wearing a red scarf encouraged me to embody the moral emotions of communism. However the scarf as a visible sign of being a Youth Pioneer, also became the sign of privilege, and functioned to produce obedience at an early age, via reproducing established systems of governance though bureaucratic systems. It shaped our behaviour, even to the point of our participation in emotionally harming ‘divergent’ peers.

How can a child make a moral judgement, when he/she submits to the collective? For me, the red scarf is a reminder that I, like others, I have passed through the valley of administrative evil – where no one is innocent, and no one is exempt.

References:

- Adams, G. B. and Balfour, D. L. (1998) ‘The Dynamics of Evil and Administrative Evil’, in Unmasking Administrative Evil. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 2–13. doi: 10.4324/9781315716640-1.

- Balfour, D. and Alibašić, H. (2016) ‘Administrative Evil’, in Farazmand, A. (ed.) Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–5. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_1119-1.

- Caton, S. C. (2010) ‘Abu Ghraib and the Problem of Evil’, in Ordinary Ethics : Anthropology , Language , and Action. New York: Fordham University Press, pp. 165–184. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13x07p9.12.

- Farmer, P. (2004) ‘Sidney W. Mintz Lecture for 2001: An anthropology of structural violence’, Current Anthropology, 45(3), pp. 305–325. doi: 139.080.239.064.

- Kleinman, A. and Kleinman, J. (1985) ‘Somatization: the interconnections in Chinese society among culture, depressive experiences, and the meanings of pain’, in Lock, M. and J. F. (ed.) Beyond the Body Proper: Reading the Anthropology of Material Life. Durham and London: Duke University Press, pp. 468–474.

Dawn Raids: the terror of racism in 1970’s NZ

Written by Amy Hema, for an assignment on ‘administrative evil’ in ANTH424.

The 1970s saw some of the darkest times for New Zealand, following the economic crash of the late 1960s. With the first waves of unemployment since the Great Depression, the country was looking for someone to blame. It was was in this context that ‘overstayers’ were deemed to be burden to New Zealand [1]. These overstayers were typically Pasifika peoples who had been actively recruited for New Zealand’s booming labour market, in the early 60’s. Now their deportation was deemed a priority.

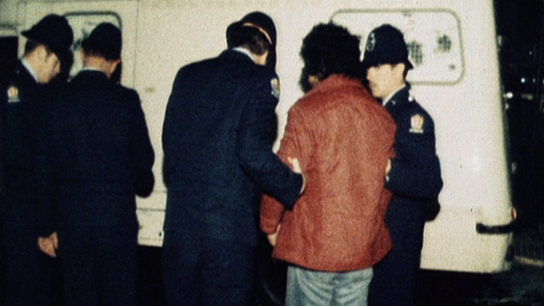

To this end in 1974 the New Zealand police began raiding houses suspected of containing overstayers, in the early hours of the morning [2]. These came to be known as the Dawn Raids. Racially motivated, and traumatising for the Polynesian population that were often the focus, this is a moment in the country’s history that largely goes undiscussed, and yet had significant impact on a people group that were marginalised, villainised and targeted by the New Zealand government and police.

A screenshot from a 2015 ‘NZ on Screen’ documentary called ‘Dawn Raids’. The image shows a Pasifika man being taken into custody by police. The documentary represents very recent attempts to acknowledge this part of New Zealand’s history. Source: https://www.nzonscreen.com/title/dawn-raids-2005

Adams and Balfour have written extensively about the relationship between administration and evil; a relationship that is often overlooked, but powerful in enforcing ‘evil’ in the sense of harm against a particular vulnerable group [3]. The Dawn Raids are a prime example of administrative and bureaucratic authority being used to enact this harm.

Discourses of Dehumanisation

Adams and Balfour argue that our daily lives are built upon are taken for granted assumptions; that we take little time to examine the way we are living and the impact it may have. Subsequently, something as fundamental as language and storytelling can make us susceptible to participating in evil without realising it[3].

The dawn raids went largely unopposed by the general public due to the language and discourse used to describe those being targeted in the raids, being unthinkingly accepted.

In a 1975 campaign run by the National Party, Polynesians were depicted as aggressive, unwelcome pests who were taking jobs away from deserving Kiwis [4]. The ad told the story of New Zealand as a peaceful nation, one that you would want to raise your children in… until the arrival of immigrants. It claimed that these immigrants became incensed by the lack of jobs, healthcare and education, and turned angry and violent.

In these ads, the blame was being placed squarely on Polynesians; the happy compliant residents depicted were white, whilst the angry individual was brown with a large afro. As such, these ads were used to create a divide between ‘us’ and ‘them’ – those who deserved to be in NZ and those who did not.

The ads created a strong and specific narrative that became a taken for granted ‘Truth’; that Polynesians were taking advantage of New Zealand’s resources and generosity, and that they needed to be removed. Referred to simply as ‘overstayers’, ‘illegals’, and ‘browns’ and presented to the public as over-the-top caricatures, a clear message was sent about who these people were, what they were doing to the country and how they should be dealt with[5]. These catch-all terms enable the individual to refer to a group without acknowledging they are individual humans, who came to New Zealand looking for a better life, instead they are just a collective problem.

In interviews taken at the time of the raids [5], New Zealanders were clearly holding tight to these narratives. As such, they became participants in evil – accepting and condoning through acceptance that a group of people be harmed by prejudicial policies and laws. Standing back and watching it happen.

Through social discourse one can readily observe the way in which language is used to dehumanise and separate the other to allow for the continuation of administrative evil – by actively reinforcing racial stereotypes, create to separate and privilege, New Zealand citizens became passive participants.

The Social Construction of Compliance

In the case of administrative evil, there are hierarchies. Specifically, there are the policy makers and the enforcers. Since the policy makers are a few steps removed from the site of violence, they are able to distance themselves from the reality of the situation. The enforcers however are on the ground, and are active participants.

Interviews with former police officers evidence the same position; they may have been overzealous in their attempts to identify and charge overstayers, but they believed their cause was just, and they were following orders[5]. Adams and Balfour have discussed these attitudes in what they call ‘the social construction of compliance’ – in which the an individual is pushed to perform violence under the direction of authority – whether or not they agree with the process becomes irrelevant as they are no longer acting as an individual but as a cog in a machine.

Adams and Balfour argue that as a culture that has come to place so much value on individualism, the USA has come to expect that when presented with a difficult choice, an individual will stick to their morals and refuse to comply[3]. Did the normative ‘Pakeha’ 1970’s New Zealand share a similar moral system? We know from the overzealous policing that during the dawn raids, the police force became aggressive in their pursual of overstayers. They stopped individuals on the street and asking for identification, in what was essentially ‘stop and frisk’, since the individuals stopped were done so based on the colour of their skin. They raided homes at the crack of dawn, deliberately when individuals and families were vulnerable.

A New Zealand police officer on Lambton Quay, in 1975. Source: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/crime/80132822/decades-investigating-darkest-crimes-does-not-dent-top-detectives-optimism?fbclid=IwAR0gWhk-M76ykJswrlncS8Rsgz4TT6-krw44NeDlEA1LNJ_5jBqvUq6948g

The actions taken by the police and the legal system were extreme, and individuals were being persecuted for minor crimes (such as petty theft) to the fullest extent of the law, at an unprecedented rate – though this was all technically legal, functioning within the system rather than as an exception to it.

Policy makers and police officers put their own opinions and feelings aside to carry out the policies set in place – even if it meant brining harm by enforcing racist ideologies. Whilst there was some push back on the stop and frisk policies, they were ultimately widely enacted by law enforcement[5]. What one can observe from the police tactics at the time is that group morality had the capacity to overrule individualism – a fact not readily embraced by many who believe in individualism.

Concluding Thoughts

Women performing at a Pacifica conference in 1975. Source: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/women-together/pacifica

What is made evident by examining the history of the Dawn Raids in New Zealand, is that administrative evil relies on both passive and active participation. By sharing narratives of harmful individuals who are taking away jobs from more deserving individuals, and upholding policies that allowed law enforcement to act on racism and stereotypes, a culture was created that allowed evil to continue in a way that was accepted by the mainstream populace.

Adams and Balfour stress that administrative evil flourishes under conditions in which people believe in the cause or adopt the ideologies as taken for granted facts – the success of administrative evil then rests in the failure to identify the evil nature of the act until it’s too late.

References

[1] ‘Dawn Raids’. nd. http://dawnraidsnz.weebly.com/

[2] New Zealand History. ‘The 1970’s. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/the-1970s/1976

[3] Adams, G. & Balfour, D.L. (2014). Unmasking Administrative Evil: the dynamics of evil and administrative evil. Sage Publications.

[4] Te Ara (1975) ‘National Party Election Campaign Ad’ https://teara.govt.nz/en/video/2158/national-party-advertisement

[5] ‘NZ/Samoan Dawn Raids’ Documentary New Zealand. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZviIkSxjV0k

Women Walking Alone: An ethnographic soundscape

A soundscape produced by Laura Gunther, for ANTH210 (Translating Culture)

About the soundscape:

The soundscape I produced for ANTH210 responded to my research question: ‘What are some of the challenging experiences of being (cisgender) female in Dunedin?’

The soundscape I produced for ANTH210 responded to my research question: ‘What are some of the challenging experiences of being (cisgender) female in Dunedin?’

This is a topic that felt most relevant to me and what was/is applicable to Dunedin culture. In order to encompass this in an audio format, I explored both my personal experiences as a woman, along with those experienced by others through a collection of audio recordings, woven together to produce the sound of a woman walking alone at night.

About the ANTH210 process:

The process of recording the soundscape audio came with its challenges; sound interruption was one of them. Many of my audio clips had to be re-recorded in order to achieve what I wanted out of my ethnographic research. Furthermore, finding relevant audio recordings came as a struggle. It came as quite a challenge to decide upon sounds produced within Dunedin that would provide me with the environment I had pictured within my mind. While this was eventually resolved, I also feared that my lack of technological experience would interfere with the quality of my soundscape, and I continued to believe this up until its submission. But thankfully, I recall that technological experience is not what defines the quality of a soundscape – rather it is its content and how it all comes together that matters.

My chosen format for the soundscape was intended to immerse the listener into the mind of a fearful woman – as many feel – when travelling alone at night. While this is not felt by all women, I wanted to produce a soundscape that was a harsh reality. Through these chosen sounds, a woman’s experiences, along with fears, is captured – producing an insight as to what a woman may experience – even in a student environment such as Dunedin.

Emmett Till: the photograph that made a martyr, started a movement

Written by Amy Hema, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424.

Emmett Till as pictured at his funeral, in an open casket; deformations the results of the violent nature of his race-based murder.

When thinking about images of evil, this photo immediately comes to mind. I was introduced to it eight years ago, and to me it has always been the epitome of evil.

The photo is of a young boy named Emmett Till, who became a martyr for the US Civil Rights movement after his tragic murder.

But how did one tragedy influence a whole country? With a photograph.

The Murder of Emmett Till

Emmett was a 14-year-old African American boy, who in the summer of 1955 travelled from his hometown [1] Chicago to Mississippi. Before boarding the train, he kissed his mother goodbye, unbeknownst to them both, for the last time.

On August 24th Emmett entered Bryant’s market in the small-town of Money.

The interaction that took place in that store has been debated for decades, but what was reported at the time was that Emmett had been inappropriate with and whistled at the white grocery clerk, Carolyn Bryant [1]

Four days after the alleged incident Carolyn’s husband and his half-brother entered the home where Emmett was staying. They kidnapped, tortured and killed Emmett before tying a cotton gin fan to his neck and throwing his body into the Tallahatchie river, where it would be discovered days later. Emmett’s body had been so badly beaten, the only way to identify him was by his father’s signet ring [1]

Photograph shows the jury at the trial of two white men, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, charged with murdering Emmett Till. 9/20/1955. Courtesy: Library of Congress

Roy Bryant and J W Milam were arrested and charged with murder.

They were tried in front of an all-white jury, in a scene Harper Lee herself could have written. After only an hour of deliberation, both Bryant and Milam were found ‘not guilty’[2].

A photo that incensed a nation

I argue that the reason why Emmett became a ‘martyr’, in the sense of his death taking on wider moral and political meaning, is because this photo of his body exists.

Emmett Till was not the first boy to be lynched. At the time, lynching was part of lived reality of African-American communities in the USA [3]. The difference for Emmett is the proliferation of this photograph. This photo exists because Emmett’s mother, Mamie Elisabeth Till-Mobley, made an incredibly difficult decision; to have an open casket funeral. Mamie had to fight for her sons remains to be returned to her, and when she received his remains, she was told the casket had to remain closed [1]

Mamie Till looks stoically over her son. David Jackson (1955). Source: Time: 100 photos http://100photos.time.com/photos/emmett-till-david-jackson NB. In other photos Mamie leans over the casket with an expression of absolute pain and grief.

However, after seeing the horrors that were inflicted upon him, Mamie knew the world had to see what she had seen[4]. The existence of this photo is the enactment of her moral obligation, to a child who could not share his story which needed to be told, and to the world that needed to hear it.

Photos of the body were circulated by Jet Magazine, capturing the brutality of the violence that Emmett had suffered. At the time, these images were circulated within African American audiences only. Being too brutal to publish in mainstream magazines, it would be years before the image became a global phenomenon.

I link this to what anthropologists Kleinman and Kleinman have discussed as the role of suppression in visual representations of suffering[5]. Withholding evidence of suffering denied the public the chance to stand as moral witnesses. The circulation of images like this often by nature only convey one ‘slice’ of a complex reality. However by choosing to not circulate his image, mainstream media outlets were denying and erasing the suffering of Emmett, his family, and the African-American community.

Emmett and the Civil Rights Movement

Kleinman and Kleinman have also argued that images have been used to confront viewers with a moral issue, and call for social action[5]. The photo of Emmett Till is a prime example of moral sentiment being used to rally people toward social justice. Sociologist Joyce Ladner coined the phrase the “Emmett Till Generation” of black activists, to describe the individuals living in the United States who after the death of Emmett Till became heavily involved with civil rights. That term offers a perfect summation of how the image impacted the lives of African Americans[6].

Many consider Emmett’s death and the circulation of the photos to be a catalyst for the civil rights movement, influential activists stated that the death of Emmett had a significant impact on their lives and consequentially their involvement with the civil rights movement. In her memoir, Anne Moody details how the death of Emmett Till made her aware of her own position within society, how after his murder she became afraid of being killed because she was black. Moody went on to describe the rage she felt, at the people who had killed Emmett and the African Americans who, out of fear, stood by and allowed these things to keep happening[7]. Moody’s personal history with the photo demonstrates how moral witnessing, in visual form, not only rallied a generation but created new understandings of how people fit into the world.

Only a few months after the circulation of Emmett’s photo, Rosa parks famously refused to give her bus seat to a white woman, leading to the Montgomery Bus Boycott. When asked why she made that decision she said, ‘I thought of Emmett Till and when the bus driver ordered me to move to the back, I just couldn’t.[4]’

Although Emmett may have not been directly responsible for the civil rights movement, his image was a confrontation of the truth; people could no longer deny that these things were happening and that they could happen to any Black American.

Why does Emmett Till still matter?

Racism still exists within the United States, albeit not in the same way it did 60 years ago. There are no signs separating water fountains or bathrooms. But racism persists in the form of stereotypes, inequality in housing, education and employment opportunities.

Racism in the USA today is the over-representation of unarmed African American teens being killed. Each time there is a killing of a black male in the US, Emmett’s name re-enters the spotlight[8], through his image he has become forever linked with racial violence. Emmett Till was the face of the Black Lives Matter Movement before it existed.

One of the most notorious killings in recent history was that of Trayvon Martin, following the murder of Martin, Emmett Till was once again thrusted into the spotlight. Trayvon and Emmett’s deaths shared a striking resemblance, as the Washington Monthly put it “Separated by a thousand miles, two state borders, and nearly six decades, two young African American boys met tragic fates that seem remarkably similar today: both walked into a small market to buy some candy; both ended up dead.[8]”

The fact that Emmett is still brought up to this day, as a representation of racism and hatred is testament to the power not only of his photo but of images in general, they are lasting, they freeze a moment in time and hold it there. Emmett will never stop being a martyr, because he has been frozen in time as one.

Despite the immense influence of this image, there is still a few glaring questions; sixty years after the circulation of the photo of Emmett, how is it that we are still in the same place? How is it that we are still being bombarded with images of African- American suffering? Have we become, as Frosh put it, desensitised [9]?

We are in a unique period where we can constantly access news and images, in every facet of our lives we are exposed to the suffering of others, but from a position that is so far removed, after a while it becomes harder to empathise. Have we become numb to these killings?

And finally, how many more Emmett Tills will we have to look upon before people change?

References:

[1] See the Documentary: ‘The Murder of Emmett Till’ (2003, PBS).

[2] PBS (n.d.) ‘The Murder of Emmett Till: The Trial of J.W. Milan and Roy Bryant’. PBS: The American Experience. Available at: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/emmett-trial-jw-milam-and-roy-bryant/

[3] In the 75 years leading up to Emmett’s death, it is estimated the over 500 African American’s were lynched within Mississippi, most of them were men accused of associating with white women. https://youtu.be/7uTtNnCw69w?t=426

[4] The Washington Post. ‘Emmett Till’s mother opened his casket and sparked the civil rights movement’. The Washington Post. Available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/07/12/emmett-tills-mother-opened-his-casket-and-sparked-the-civil-rights-movement/

[5] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. 1996. ‘The Appeal of Experience; the dismay of images: Cultural Appropriations of sufferings in our times.’ Daedalus, 125(1).

[6] Kolin, P.C. The Legacy of Emmett Till

[7] Moody, A. (1968) Coming of Age in Mississippi. Penguin Randomhouse reprint.

[8] Gorn, E.J. (2018). ‘Why Emmett Till still matters’ Chicago Tribune. July 20th. Available: https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-perspec-emmett-till-mississippi-murder-reinvestigation-whistle-white-woman-carolyn-bryant-20180722-story.html

[9] Frosh, P. (2018). ‘The Mouse, the screen and the holocaust witness: Interface aesthetics and moral response’, New Media & Society, 20(1), pp351-368.

Hip-hop Dunedin: An ethnographic soundscape

A soundscape produced by Biruk Mengstu, for ANTH210 (Translating Culture)

About the soundscape:

My research question was around the influence of Hip-hop on some students in Dunedin. All these sounds were retrieved from the fieldwork (studio apartment and live underground hip hop showcase) and reconstructed to tell a story of the extent of influence hip-hop has on these students.

My research question was around the influence of Hip-hop on some students in Dunedin. All these sounds were retrieved from the fieldwork (studio apartment and live underground hip hop showcase) and reconstructed to tell a story of the extent of influence hip-hop has on these students.

About the ANTH210 process:

Throughout my high school and university life, I have always been interested in the natural science field. However, I have always wanted to learn more about my surroundings and the social science aspect. When I found out about the ANTH210 paper, I thought it would be an excellent opportunity to challenge myself and to get out of my comfort zone as I have never taken an anthropology paper before.

This paper has opened my mind to a different way of thinking and has shown me that there are so many different cultures that are all around which we sometimes don’t realise. This paper has allowed me to get in touch with my creative side, which I never really had the chance to express before. Overall I enjoyed and learned a lot by being a part of the Anthropology 210 (Translating Culture) class.

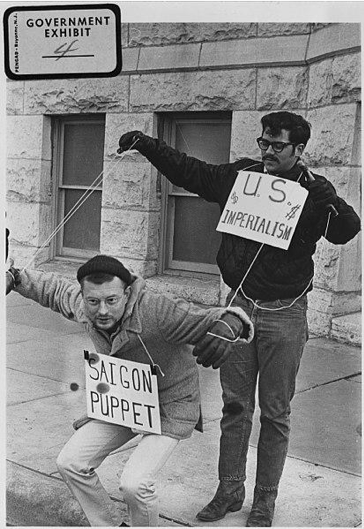

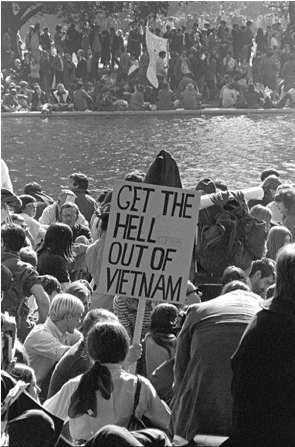

The execution of politics: how one photo of a Viet Cong prisoner shaped the war

*Trigger warning: Violent image*

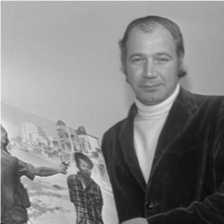

I came across this particular image during my own personal exploration into global politics following World War II, in an online article about American politicians. I was shocked after reading into the caption, to find that in this image the man is already dead, with the bullet either still passing through his head, or having just passed through it.

I find this attitude towards this extremely violent situation quite striking. Even with an understanding that extensive exposure can lead to stoicism, it is intriguing to me that one can

I find this attitude towards this extremely violent situation quite striking. Even with an understanding that extensive exposure can lead to stoicism, it is intriguing to me that one canBy capturing and conveying suffering through visual imagery, the photographer becomes a witness of death, but also a moral actor. Adams believed two people were killed in that instant, “the general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera”6.

Mobilising Support for Social Action

Kleinman and Kleinman5 emphasise that visual representations of evil can be used to promote social action. Indeed this image slowly became an icon for American activism, and to this day serves as a reminder of the atrocities that arise from political conflicts. This photo was a “classic instance of the use of moral sentiment to mobilize support for social action”. A fellow Vietnam War photographer, David Hume Kennerly, put it this way: “I don’t know that it ended the Vietnam War, but it sure as hell didn’t help the cause for the government – one thing I know for sure, anybody who’s ever seen that photo has never forgotten it”.6

Kleinman and Kleinman5 emphasise that visual representations of evil can be used to promote social action. Indeed this image slowly became an icon for American activism, and to this day serves as a reminder of the atrocities that arise from political conflicts. This photo was a “classic instance of the use of moral sentiment to mobilize support for social action”. A fellow Vietnam War photographer, David Hume Kennerly, put it this way: “I don’t know that it ended the Vietnam War, but it sure as hell didn’t help the cause for the government – one thing I know for sure, anybody who’s ever seen that photo has never forgotten it”.6

The image was used to give a glimpse into the reality for those enduring such brutality, and conveyed a powerful intimacy and desperate message to the people of the USA. It is still considered in the USA to be the “Photo That Changed the Course of the Vietnam War”1.

Appropriating Suffering

This image meant that the death of the Viet Cong prisoner would not go unremembered. As Astor says, “this last instant of his life would be immortalized on the front pages of newspapers nationwide”1. However Kleinman & Kleinman5 also discuss how the suffering depicted in an image can be taken advantage of, particularly in the way that it is distributed and consumed. As is stated in their article, the use of an image to ‘right an inhumane situation’ can be inhumane in itself.

The image of suffering above was used by the American anti-war effort to serve a purpose; as a tool in the process of stopping the Vietnam War, but at what cost? The image may have succeeded in saving many lives by cutting the war shorter, however, the insensitive use of the image was disastrous for some.

For the victim’s wife, Nguyen Thi Lop3, the image served a very different purpose than it’s anti-war role in the US. For her, the use of the image played the role of messenger: informing Nguyen of her husband’s death. In a clip years on, Nguyen is recorded saying in Vietnamese that “a friend of mine brought me the newspaper and then I found out what had happened to my husband”.

The reproduction of this image did not allow this widow the privacy or respect that she deserved. It shows lack of understanding, respect and permission required in the distribution of material. Furthermore we can argue that to share the intimate destruction of human life with such a level of triviality (as glancing past it in a newspaper) de-sensitizes, and reduces from the pain of the victim. Kleinman and Kleinman explain:

“Suffering ‘though at a distance,’ is routinely appropriated in American popular culture, which is a leading edge of global popular culture. The globalization of suffering is one of the more troubling signs of the cultural transformations of the current era: troubling because experience is being used as a commodity, and through this cultural representation of suffering, the experience is being remade, thinned out, and distorted”.5

One effect of this, they argue, is the erasure and distortion of the importance of social experiences of suffering. In this case, the image itself can not inherently convey the contextual political systems that produced it; its literal content is simply a violent act between two individuals. Yet re-contextualised as part of the anti-War effort, it did serve to highlight wider political contexts, such that the social response to the image led to not only condemnation of the violent act by that one soldier, but a change in public attitudes towards US involvement in Vietnam, and eventually a shift in political decisions by the US.

Conclusion

Visual depictions of suffering can be used to make us aware of the suffering experienced in other parts of the world. These visual depictions have the potential to be used as a tool to support social movements. However, the use of images does have its limitations and concerns, transforming the intimate suffering of real people into a tool. It is still up to debate whether this is an acceptable price for social change, and who gets to drive the production and circulation of such images, what they mean, and for what purpose.

References

- Astor, M. (2018, February 1). A Photo That Changed the Course of the Vietnam War. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/01/world/asia/vietnam-execution-photo.html

- Watson, A. M. (2015). PULITZER PRIZE PHOTOGRAPHY: SAIGON EXECUTION. Retrieved from http://www.newseum.org/2015/05/12/pulitzer-prize-photography-saigon-execution/

- VIETNAM: VIETNAM WAR ANNIVERSARY: MEDIA (2). (2000).. Retrieved from http://www.aparchive.com/metadata/youtube/3061fe038ddb4dece288d433331d7b91

- Adler, M. (2009). The Vietnam War, Through Eddie Adams’ Lens.All Things Considered. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2009/03/24/102112403/the-vietnam-war-through-eddie-adams-lens

- Kleinman, A. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1–23. Available at: https://ezproxy.otago.ac.nz/login?url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027351. ISSN: 00115266

- Ruane, M. E. (2018, February 1). A grisly photo of a Saigon execution 50 years ago shocked the world and helped end the war. Washington Post. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/02/01/a-grisly-photo-of-a-saigon-execution-50-years-ago-shocked-the-world-and-helped-end-the-war/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.5374c97d4477

- Prescott, T. L. Appropriation and Representation. Image Journal, (97). Retrieved from https://imagejournal.org/article/appropriation-and-representation/

- Mitchell, R. (2018, March 31). A ‘Pearl Harbor in politics’: LBJ’s stunning decision not to seek reelection. Retrieved April 26, 2019, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/03/31/a-pearl-harbor-in-politics-lbjs-stunning-decision-not-to-seek-reelection/?utm_term=.cdd2e6ec89aa

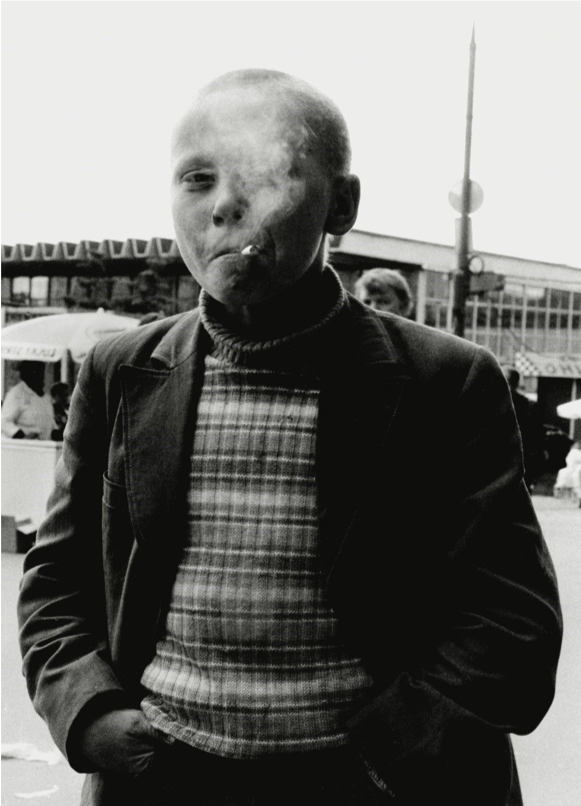

The Smell of Suffering: Portrait of a Street Boy

Written by Yi Li, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

Street photographers visualise social suffering through their artwork. They engage (themselves and us) with unfamiliar experiences: shrinking cities, strange portraits. Photographers can function as both moralists and anthropologists. They are often spectators, often self-exiles – presenting a version of evil for others to interpret, but often also fulfilling their own sense of moral obligation.

My argument is that both the positionality of the street photographer, and the medium of the photograph, means that photos sometimes break free from the time and space, conveying a universalism of personal adversity. I use an example of street photography of homeless in Moscow to discuss this.

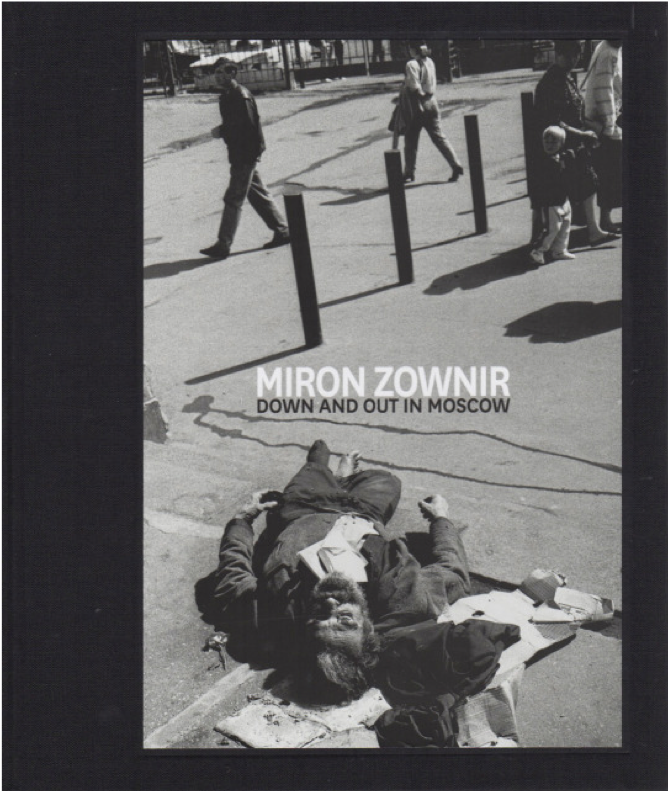

Down and Out

German photographer Miron Zownir is one of the most radical contemporary examples. His focus on marginal characters and the dark side of cities is rooted in his childhood. A Ukrainian-German who grew up in post-war Germany, Zownir as a teenager immersed himself in Eastern European literature without trusting any existing political systems or social stereotypes. His inherent interest in individualists inspired him to live in slum-like places, capturing streets with an anti-establishment attitude.

The street portrait is from Miron Zownir’s publication Down and Out in Moscow, a series of images that captured the homeless crisis in the Russian capital in 1995, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

I noticed the smoking boy with an adult expression to his cynical appearance when I first came across it in 2018. It is somehow different from the other challenging photos in his book. Momentarily, the encounter between Miron Zownir and the boy constructed a story about how individuals were abandoned by society. The diffusing cigarette smoke in front of the boy seems to allow me to smell the evil that permeated the city.

Kleinman & Kleinman (1996)[i] discuss the moral implications of photographs, through contextualising engagements within creators, audiences and images.

Zownir’s photographic experience runs through the technical transition: turning from black-and-white film to digital photography in the post-modern era. This photo was captured in a classic form, of black and white portraiture displayed in gallery spaces, and print journalism (books, and magazines). But it is worth noting that the extended agency of photographs can shift, depending on medium, from a momentary, regional realm to a worldwide standing discussion, through different forms of reprinting and representing.

How different would the viewers experience of this boy’s suffering be, scrolling past a small version in a social media feed? Touching his face on a tablet?

Moral Obligation in Street Photography: Unperceived Suffering as Social Experience

Anthropologists may ask: what is the basis of a photographer’s sense of moral obligation to take photos on streets?

Street photography concentrates on people and their behaviour in public, thereby also recording personal history: though without formal consent, and with the combination of spontaneity, outsider perspective, and private exploration. These subjects of circumstances are generally unaware – either stared at or ignored until they were documented. Street photography uses these collected narratives to define cultures or places, with no duty to serve a larger whole, and no limitation on how they reconstruct these places[ii].

Kleinman & Kleinman considered that photographers represent individual suffering as part of social experience, for others to access – whether these are extreme or ordinary forms of suffering. But as anthropologists, they caution that “there is no timeless or spaceless universal shape to suffering,” (1996, p:2).

In Down and Out in Moscow, Miron Zownir photographed death, sin, and a harsh lived reality. Underlying the powerless state, the rampantly violent proliferation pushed Moscow to become a hotbed of criminal forces in the 1990s; “the most aggressive and dangerous city, … people were dying right there on the street”.[iii] Such tension immediately changed Zownir’s original mission: to document Moscow’s nightlife with three-month project funding from a photographic committee.

Suffering is one of the existential grounds of human experience, and Kleinman & Kleinman suggest that moral witnessing also must involve a sensitivity to others, albeit with unspoken moral and political assumptions. Still functioning as a photographer, Zownir did not tend to query the government, or alter Moscow residents’ condition – but instead chose to live briefly in this shadowed twilight zone, to experience the nightmare.

Individual into the Universal: Reflexive Appreciation against the Silent Oblivion

How can we perceive a stranger’s suffering as universal? Here, a street boy’s sophisticated body language is beyond verbal expressions: dressing in a suit over a horizontal striped turtleneck sweater, his hands are hidden in his pants pockets like a social youth. He looks indifferent to the surroundings and unmoved by the photographer. He is clothed, unlike many beggars, and yet he was banished to a community where no-one had a home.

This portrait reminded me of the 1994 film In the Heat of the Sun. The film is based on Chinese writer Wang Shuo’s novel Wild Beast, which is set in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution, and tells how a teenage boy and his friends are free to roam the streets day and night in a period in which all the social and educational systems are extremely non-functional. Both protagonists are undergoing suffering – the film an example of the way their individual experiences can be abstracted and universalised, for the consumption of a wide variety of audiences. Yet this this also shows us how images and films can provide an insight into personal suffering that is usually invisible – although the harsh realities behind the lives they represent often go on unchanged.

The unwitting suffering of Zownir’s street boy is entangled with the political unrest in Moscow. But as a photograph, it also exists apart from the historical context: “a professional transformation of social life […] a constructed form that ironically naturalised experience.”[iv]

The frame itself cannot communicate this context. Yet it can communicate something else – the universality of human feeling event amidst diverse and ethically incommensurable [v] societies. Perhaps this is the power of portraiture – indeed the seminal psychological research of Ekman, and others, has asserted that emotional expression on faces is universal [vi] – meaning that moods and feelings may at times transcend cultural limitations, an idea often grappled with in the anthropology of emotion.

Conclusion: photography as a container of truth and imagination

Miron Zownir wrote in his poetry: When the earth returns with a thousand sunsets, the truth of the universal is darkness.[vii]

Photography blurs social facts, but seals emotions. Whether the boy would recognise the chaos, ignorance and madness that Zownir’s book communicates, in his free childhood in post-collapse Moscow, cannot be known. Yet seeing this photo as a cultural artefact, we can recognise that both the photographer and the audience as complicit in reproducing and politicising fragmented histories in photography. The photograph becomes a container for these forms of imagination.

Several years later after this photo was taken, when Miron Zownir was back in Moscow for his upcoming exhibition, the city’s exterior had been cleaned up. The silent responses of audiences standing in front of an enlarged version of this photograph, seemed at a vast remove from its original context. What meaning, what comfort, did it hold then? Yet the world still calls for images, as ‘the mixture of moral failures and global commerce is here to stay’ (Kleinman & Kleinman 1996: p. 7).

References:

[i] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[ii] Levy, S. (2019) ‘Street photography as a process’ in Lens Culture Guide to Street Photography, pp. 8-12

[iii] Zownir, M. (2014) ‘I was always an individualist’, Berlin Interviews, by Katerina, http://berlininterviews.com/?p=1375.

[iv] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[v] Fassin, D. (2009) ‘Beyond good and evil?: Questioning the anthropological discomfort with morals.’, Anthropological Theory. Sage, 8(4), pp. 333–344.

[vi] Ekman P, Friesen W (1976). Pictures of Facial Affect. Consulting Psychologists Press : Palo Alto.

[vii] Zownir, M. (2018) ‘Black’, Vision

Healing the Self: Motivational Speakers as Shamans

Written by: Emma Gamson

[Adapted from an essay written for ANTH228/328: Anthropology of Religion and the Supernatural]

Motivational speaking is a category of verbal performance where the goal is to inspire or motivate an audience 12. Motivational speakers tend to share self-narratives, to convey messages of hope, reassurance and success 8. There is no training or certification required; success depend on an individual speakers’ popularity 8, 9.

Tony Robbins is a highly influential motivational speaker whose messages focus on empowerment, self-transformation and “unleashing the inner-self” 14, 7.

Tony Robbins presents his talk ‘Why We Do What We Do’ at the February 2006 TED conference. The image shows Robbins open and powerful stage presence as he addresses as audience. Source: https://www.ted.com/talks/tony_robbins_asks_why_we_do_what_we_do

This post analyses some of Robbins’ performances, to argue that motivational speaking can be understood as a type of healing practice. I apply concepts from the anthropology of religion, such as liminality, communitas, and ritual, to understand how he frames the self, how he establishes legitimacy, and how he enacts healing.

Narrating your self into (a new) existence

Understandings of the ‘self’ varies cross-culturally. Greek philosophers Plato, and later Descatres, as well as much of early Christian thought, supported a dualist view of the person, in which the body is a physical, mechanical and matter of science, and the mind (in which the person or ‘self’ resides) is non-physical, spiritual and a matter of the church 16, 17. Conversely, Freud, Foucault, Sartre and Social Sciences have supported a non-dualism in which the self is made up of a body and mind immediately connected to each other, and both are subject to the influence of society and power 16. In anthropology, the ‘self’ is typically associated with the perception of one’s own existence, and is different to ‘identity’, which is more related to how ones existence is placed in relation to others 17.

People’s sense of their ‘self’ is formed by self-narrative. In other words the stories we tell about ourselves (to others, and to ourselves), have the potential to continually reconstruct who we understand ourselves to be. 6. In this way self-narratives express an individual’s agency. However they also tend to reflect frameworks laid out by wider social structures (e.g. around gender, age, class) 6.

People’s sense of their ‘self’ is formed by self-narrative. In other words the stories we tell about ourselves (to others, and to ourselves), have the potential to continually reconstruct who we understand ourselves to be. 6. In this way self-narratives express an individual’s agency. However they also tend to reflect frameworks laid out by wider social structures (e.g. around gender, age, class) 6.

Robbins uses narrative to convey themes of self-renewal, self-help and power of a true inner self, all of which he claims are controlled by state of mind and worldview 2, 15. His key argument is that “you can sculpt the person you want to be with whatever raw material you have available, so long as you acknowledge the early forces that shaped you” 15.

Processes of self are not just about the mind, but about the body too. In anthropology, embodiment theory emphasises the intimate connection between mind, body and culture (in in fact seeks to challenge these as separate categories, all together). Many motivational speakers also take a holistic view, including Tony Robbins, who treats the mind and body as distinct, but directly influencing each other 15.

Religion, ritual, and self-transformation

Ritual practice is a key feature of religion. Rituals can work to express meaning, and apply religious worldviews to daily life 11. Religious worldviews can form the framework against which individuals develop and create their self-narratives. Religious ritual deeply embeds this frameworks through embodied (implicit) and explicit knowledge of one’s self in the context of the world, consequently influencing how one perceives and acts in the world 11.

Tony Robbins on stage at one of his ‘Unleash the Power Within’ seminars. A three-and-a-half-day event oriented towards helping “you unlock and unleash the forces inside you to break through your limitations and take control of your life”. The image is a snapshot showing Robbins enthusiastic and big gestures that are incorporated into his stage performances. Source: https://www.tonyrobbins.com/events/unleash-the-power-within/

As a motivational speaker, Tony Robbins employs embodied, ritualized action in a way similar to religious practice. His talks verbally lay out a worldview in which individuals have an ‘inner power’. Then his rituals make this true by enacting the ‘unleashing’ of this power with bodily action 8, 15, 14.

Specifically, Robbins his audience to participate through verbal agreement 2, 15. Their vocal articulations are a ritual way of unleashing this power. By getting his audience to respond through an embodied ritual of call-and-response, in his talks and seminars, he is asking them to reposition their own self within this worldview; to re-write their self-narrative according to that. In shifting the framework for their story, he shifts the story and thus the self.

Why does ritual work? Hot coals and big crowds

The effectiveness of Robbin’s performance is contingent on his audience. Religion is a dynamic product of human activity that tends to revolve around a central source of legitimacy or authority, but this must be continuously performed, negotiated, reproduced and validated by participants and audience members 1.

A seminar attendee calmly walks across a path of hot coals, embodying the beliefs and ideas that have been taught by Robbins. Behind cheers him on as they people queue for their turn. Source: http://morewealthandhealth.com/tony-robbins-fire-walk-review-read-fire-walk/

Robbins continuously negotiates and reinforces his authority when he prompt action from the audience. For example, Robbins created a ritualized action of walking over hot coals to show the power of the inner self, which many people have attempted 15. The offer would be absurd if the audience did not reinforce and embody support by actually attempting the walk, thus continuing to reinforce and legitimize the authority of Robbins and his worldview.

One key feature in the effectiveness of motivational speaking, is liminality. Anthropologists understand liminality as an intermediary stage in a ‘rite of passage’ ritual, which typically focuses on shifting someone’s social positionality. Like most motivational speakers, Robbins does indeed emphasizes ‘transformation’. We can argue that he uses his events to create a liminal space in which the possibilities for transformation occurs.

Communitas can be experienced in ‘coming of age’ rituals, rock concerts, sports games, prisons, religious events, and more.

The liminal stage is the ‘in between’ stage, and when lots of people are experiencing this together, it can lead to a state called ‘communitas’. Communitas is a state of anti-structure, where usual social boundaries and identities temporarily fall away, and people feel joined by bonds of common feeling 18. Liminality and communitas can both facilitate, acute moments of self-transformation.

Despite the perception of motivational speaking as an ‘individualistic’ form of healing, communitas appears to emerge again in ritualised acts in which Robbins’ audience participants respond collectively, rather than individually 18. After all, would it work the same if we was alone in a room with someone? His seminars can become a space of communitas – the audience all are temporarily separated from their normal lives, and united with others in their intense experiences in that room. It is together that they are remade.

Healing: is Tony Robbins a shaman?

People attending Tony Robbins talks seek empowerment. It is fair to infer then that they come with some sense of deficiency or disempowerment – while their bodies may be healthy, their ‘self’ is in need.

Religion is one framework of meaning that can help individuals make sense of what it means to have or to lose health, what it means to be lacking or whole10. While not a religion, Robbin’s talks similarly offer a framework of meaning that locate the cause of problems, and their solution, within a particular set of symbols and ideas: i.e. about ‘inner power’ and how to ‘unleash it’, and what effects (on both body and mind) this can have.

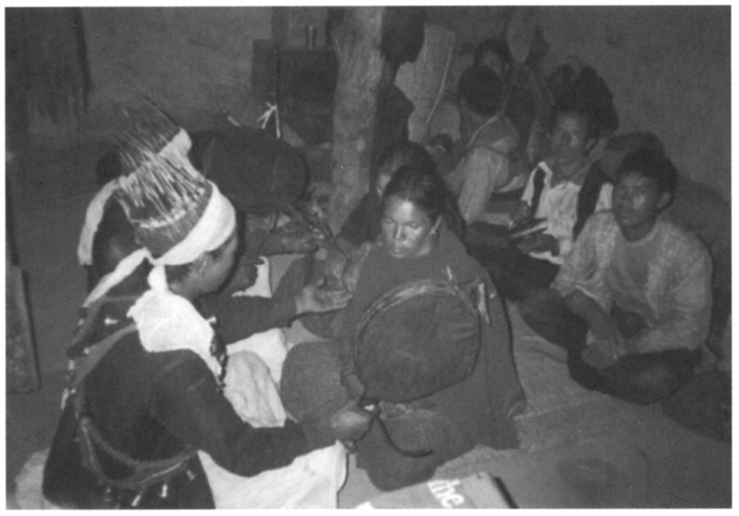

A shamanic healing ceremony, showing the jhākri (Nepali shaman) alongside a woman undergoing the healing process. Behind is a group who are also participating in and supporting the ritual (Sidkey 2010, p219)

There are similarities in particular with the way Toby Robbins works, and what anthropologists have observed of some shamanic traditions. For example, Yolmo shamans define health by the aesthetics of balance, wholeness and harmony to determine health 4. These values are embodied in the daily life of Yolmo society, embedding them in the body and shaping sensory experiences of health 4, 5. Shamans may conduct rituals involving trance states with vivid imagery to deal with illness such as soul loss 4, 5. This process not only relies on the action of the shaman themselves, but also through the participation of everyone present, including the patient 4, 5. This exemplifies the dynamic relationship between the authority of the religious healer, the participants and the social embodiment of values as key in making sense of the process of healing.

Tony Robbins seems to define health as a unity between how one lives their life and the cultivation of the power of their inner-self to create fulfilment and wellbeing. For example, in a video Robbins guides Rechaud, a 30-year-old man with a stutter, through a ritualized process of searching through memories for a cause of the stutter and bringing out Rechaud’s ‘inner warrior’ 13. Rechaud emerges ‘healed’ from his stutter and delivers a speech at one of Robbins seminars, acting as a symbol of success for this method of healing, which generated intense emotional responses from the crowd 13.

As with the Shamanic trances, Robbins guides Rechaud through a ritualized process of self-narrative that taps into imagery embedded in memories and in the symbol of the self as a ‘warrior’, to transform Rechaud and unify his inner self with his physical body to overcome the stutter.

Conclusion:

Motivational speakers in Anglo-American nations are not unlike shamans in a variety of other cultural settings – they are a culturally sanctioned form of (non-biomedical) healer, with accepted social authority. In observing Tony Robbins’ techniques, we can see how he uses this authority to lead audiences through rituals that facilitate a shift in self. His motivational seminars become a liminal space in which people are taken through a process of re-making their own narratives according to the framework he lays out, and thus are able to heal body, mind, and ‘self’.

References

- Bielo, J. S. (2015), ‘Who do you trust?”, Anthropology of Religion: The Basics, London: Routledge, 106-134

- BigMindSuccess (2017), ‘TONY ROBBINS 2016/2017 Change Your Life’, available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3jmTuzPEXTY [accessed 4th Sept 2018]

- Csordas, J. J. (1990), ‘Embodiment as a Paradigm for Anthropology ’, American Anthropological Association, 18(1), 5-47, available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/640395.

- Desjarlais, R.R. (1992), ‘Yolmo Aesthetics of Bode, Health and ‘Soul Loss’’, Department of Social Medicine, 34(10), 1105-1117

- Desjarlais, R.R. (1992) ‘Chapter 1: Imaginary Gardens with Real Toads’, Body and Emotion: The Aesthetics of Illness and Healing in the Nepal Himalayas. University of Pensylvannia Press, 3–35.

- Dunn, C. D. (2017), ‘Personal Narratives and Self-Transformation in Postindustrial Societies’, Annual Review of Anthropology, 46, 65-80, available: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102116- 041702

- Gabuna, R. (2017), ‘The world’s top 50 most popular motivational speakers’, available: speakerhub.com

- Gilbert, M. (2002), ‘Why the motivation business is booming’, Ebony, 58(2), 134-136, available: books.google.co.nz/books

- Guillebeau, C. (2010), ‘How to Be a Motivational Speaker’, available: www.psychologytoday.com

- Idler, E. L. (1995), ‘Religion, Health, and Nonphysical Senses of Self ’, Social Forces, 74(2), 683-704, available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2580497

- Lambek, M. (2014), ‘What is “Religion” for Anthropology? And What Has Anthropology Brought t Relgion?’, in Boddy, J & Lambek, M. eds., Companion to the Anthropology of Religion, Somerset: Wiley, 1-3

- Oxford University Press (2018), ‘Motivational Speaking’, available: en.oxforddictionaries.com

- RobinHood (2013), ‘Tony Robbins – 30 years of stuttering cured in 7 minutes!’, available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3eOJaprDCDA [accessed 4th Sept 2018

- Robbins Research International, INC. (2018), ‘About Tony Robbins’, available: https://www.tonyrobbins.com/biography/

- Sandmaier, M. (2017), ‘The Tony Robbins Experience’, Psychotherapy Networker, 41(6), 42-46, 58-59, available: https://search.proquest.com/docview/2075729169?accountid=14700

- Synnott, A. (1992), ‘Tomb, Temple, Machine and Self: The Social Construction of the Body’, The British Journal of Sociology, 43(1), 79-110, available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/591202 .

- Sökefeld , M. (1999), ‘Debating Self, Identity, and Culture in Anthropology ’, Current Anthropolgy, 40(4), 417-448, available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/200042

- Turner, V. (1969). ‘Liminality and Communitas’ (Abridged) in Michael Lambek (ed.) A Reader in the Anthropology of Religion. (2008)

- Sidkey, H. (2010), ‘Perspectives on Differentiating Shamans from other Ritual Intercessors’, Asian Ethnology, 69(2), 213-240, available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40961324

Incels ‘cash out’: gendered violence and the economies of hate

Posted on by smisu13p

A post written by Jazzlin Carr, based on an ANTH424 assignment.

“He doesn’t seem like that bad of a guy. He just seems hurt, like he just wants a friend or support. I always thought incels were really bad people, but he seems like a good version of them.”

I looked over at my very liberal, ultra-feminist, Jacinda Ardern-loving partner in disbelief. We had just finished watching a YouTube video from the channel Jubilee entitled “I’m An Incel. Ask Me Anything.”.[1] The short clip features a self-proclaimed incel responding to questions from the public. While his identity is hidden from those asking the questions, he is shown to the camera.

A screenshot of the Youtube video “I’m an Incel, Ask Me Anything” posted by Jubilee. In this particular frame, a woman appears to be pointedly interrogating an incel named Derrick, whose demeanour and open palms facing up depict a certain passivity and openness. Source: https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=incel