The execution of politics: how one photo of a Viet Cong prisoner shaped the war

*Trigger warning: Violent image*

I came across this particular image during my own personal exploration into global politics following World War II, in an online article about American politicians. I was shocked after reading into the caption, to find that in this image the man is already dead, with the bullet either still passing through his head, or having just passed through it.

I find this attitude towards this extremely violent situation quite striking. Even with an understanding that extensive exposure can lead to stoicism, it is intriguing to me that one can

I find this attitude towards this extremely violent situation quite striking. Even with an understanding that extensive exposure can lead to stoicism, it is intriguing to me that one canBy capturing and conveying suffering through visual imagery, the photographer becomes a witness of death, but also a moral actor. Adams believed two people were killed in that instant, “the general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera”6.

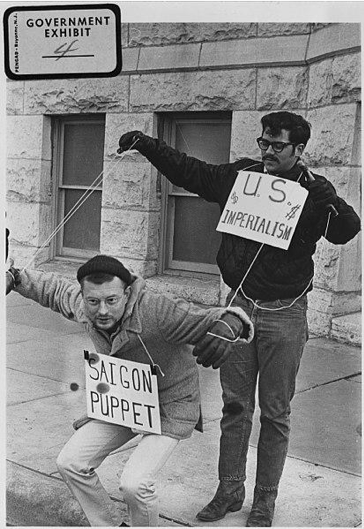

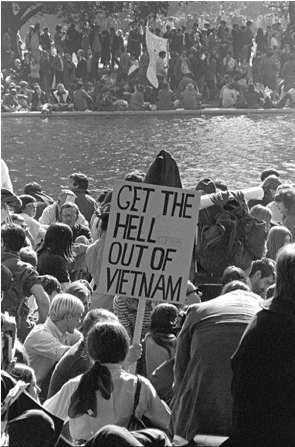

Mobilising Support for Social Action

Kleinman and Kleinman5 emphasise that visual representations of evil can be used to promote social action. Indeed this image slowly became an icon for American activism, and to this day serves as a reminder of the atrocities that arise from political conflicts. This photo was a “classic instance of the use of moral sentiment to mobilize support for social action”. A fellow Vietnam War photographer, David Hume Kennerly, put it this way: “I don’t know that it ended the Vietnam War, but it sure as hell didn’t help the cause for the government – one thing I know for sure, anybody who’s ever seen that photo has never forgotten it”.6

Kleinman and Kleinman5 emphasise that visual representations of evil can be used to promote social action. Indeed this image slowly became an icon for American activism, and to this day serves as a reminder of the atrocities that arise from political conflicts. This photo was a “classic instance of the use of moral sentiment to mobilize support for social action”. A fellow Vietnam War photographer, David Hume Kennerly, put it this way: “I don’t know that it ended the Vietnam War, but it sure as hell didn’t help the cause for the government – one thing I know for sure, anybody who’s ever seen that photo has never forgotten it”.6

The image was used to give a glimpse into the reality for those enduring such brutality, and conveyed a powerful intimacy and desperate message to the people of the USA. It is still considered in the USA to be the “Photo That Changed the Course of the Vietnam War”1.

Appropriating Suffering

This image meant that the death of the Viet Cong prisoner would not go unremembered. As Astor says, “this last instant of his life would be immortalized on the front pages of newspapers nationwide”1. However Kleinman & Kleinman5 also discuss how the suffering depicted in an image can be taken advantage of, particularly in the way that it is distributed and consumed. As is stated in their article, the use of an image to ‘right an inhumane situation’ can be inhumane in itself.

The image of suffering above was used by the American anti-war effort to serve a purpose; as a tool in the process of stopping the Vietnam War, but at what cost? The image may have succeeded in saving many lives by cutting the war shorter, however, the insensitive use of the image was disastrous for some.

For the victim’s wife, Nguyen Thi Lop3, the image served a very different purpose than it’s anti-war role in the US. For her, the use of the image played the role of messenger: informing Nguyen of her husband’s death. In a clip years on, Nguyen is recorded saying in Vietnamese that “a friend of mine brought me the newspaper and then I found out what had happened to my husband”.

The reproduction of this image did not allow this widow the privacy or respect that she deserved. It shows lack of understanding, respect and permission required in the distribution of material. Furthermore we can argue that to share the intimate destruction of human life with such a level of triviality (as glancing past it in a newspaper) de-sensitizes, and reduces from the pain of the victim. Kleinman and Kleinman explain:

“Suffering ‘though at a distance,’ is routinely appropriated in American popular culture, which is a leading edge of global popular culture. The globalization of suffering is one of the more troubling signs of the cultural transformations of the current era: troubling because experience is being used as a commodity, and through this cultural representation of suffering, the experience is being remade, thinned out, and distorted”.5

One effect of this, they argue, is the erasure and distortion of the importance of social experiences of suffering. In this case, the image itself can not inherently convey the contextual political systems that produced it; its literal content is simply a violent act between two individuals. Yet re-contextualised as part of the anti-War effort, it did serve to highlight wider political contexts, such that the social response to the image led to not only condemnation of the violent act by that one soldier, but a change in public attitudes towards US involvement in Vietnam, and eventually a shift in political decisions by the US.

Conclusion

Visual depictions of suffering can be used to make us aware of the suffering experienced in other parts of the world. These visual depictions have the potential to be used as a tool to support social movements. However, the use of images does have its limitations and concerns, transforming the intimate suffering of real people into a tool. It is still up to debate whether this is an acceptable price for social change, and who gets to drive the production and circulation of such images, what they mean, and for what purpose.

References

- Astor, M. (2018, February 1). A Photo That Changed the Course of the Vietnam War. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/01/world/asia/vietnam-execution-photo.html

- Watson, A. M. (2015). PULITZER PRIZE PHOTOGRAPHY: SAIGON EXECUTION. Retrieved from http://www.newseum.org/2015/05/12/pulitzer-prize-photography-saigon-execution/

- VIETNAM: VIETNAM WAR ANNIVERSARY: MEDIA (2). (2000).. Retrieved from http://www.aparchive.com/metadata/youtube/3061fe038ddb4dece288d433331d7b91

- Adler, M. (2009). The Vietnam War, Through Eddie Adams’ Lens.All Things Considered. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2009/03/24/102112403/the-vietnam-war-through-eddie-adams-lens

- Kleinman, A. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1–23. Available at: https://ezproxy.otago.ac.nz/login?url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027351. ISSN: 00115266

- Ruane, M. E. (2018, February 1). A grisly photo of a Saigon execution 50 years ago shocked the world and helped end the war. Washington Post. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/02/01/a-grisly-photo-of-a-saigon-execution-50-years-ago-shocked-the-world-and-helped-end-the-war/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.5374c97d4477

- Prescott, T. L. Appropriation and Representation. Image Journal, (97). Retrieved from https://imagejournal.org/article/appropriation-and-representation/

- Mitchell, R. (2018, March 31). A ‘Pearl Harbor in politics’: LBJ’s stunning decision not to seek reelection. Retrieved April 26, 2019, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/03/31/a-pearl-harbor-in-politics-lbjs-stunning-decision-not-to-seek-reelection/?utm_term=.cdd2e6ec89aa

Selling Che: the commodification of a communist icon

Written by Jayden Glen, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

Images are powerful. They can inspire fear, love and even sadness. As the common saying goes, ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’. But images can be manipulated out of their original context, and be used to enforce values against their original intention, as shown by the commercial circulation of images of Che Guevara.

Giving Context to the Iconic Image

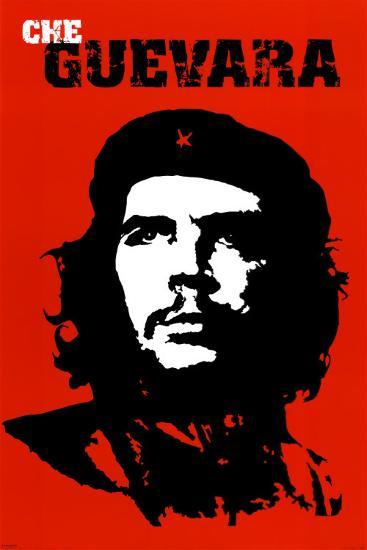

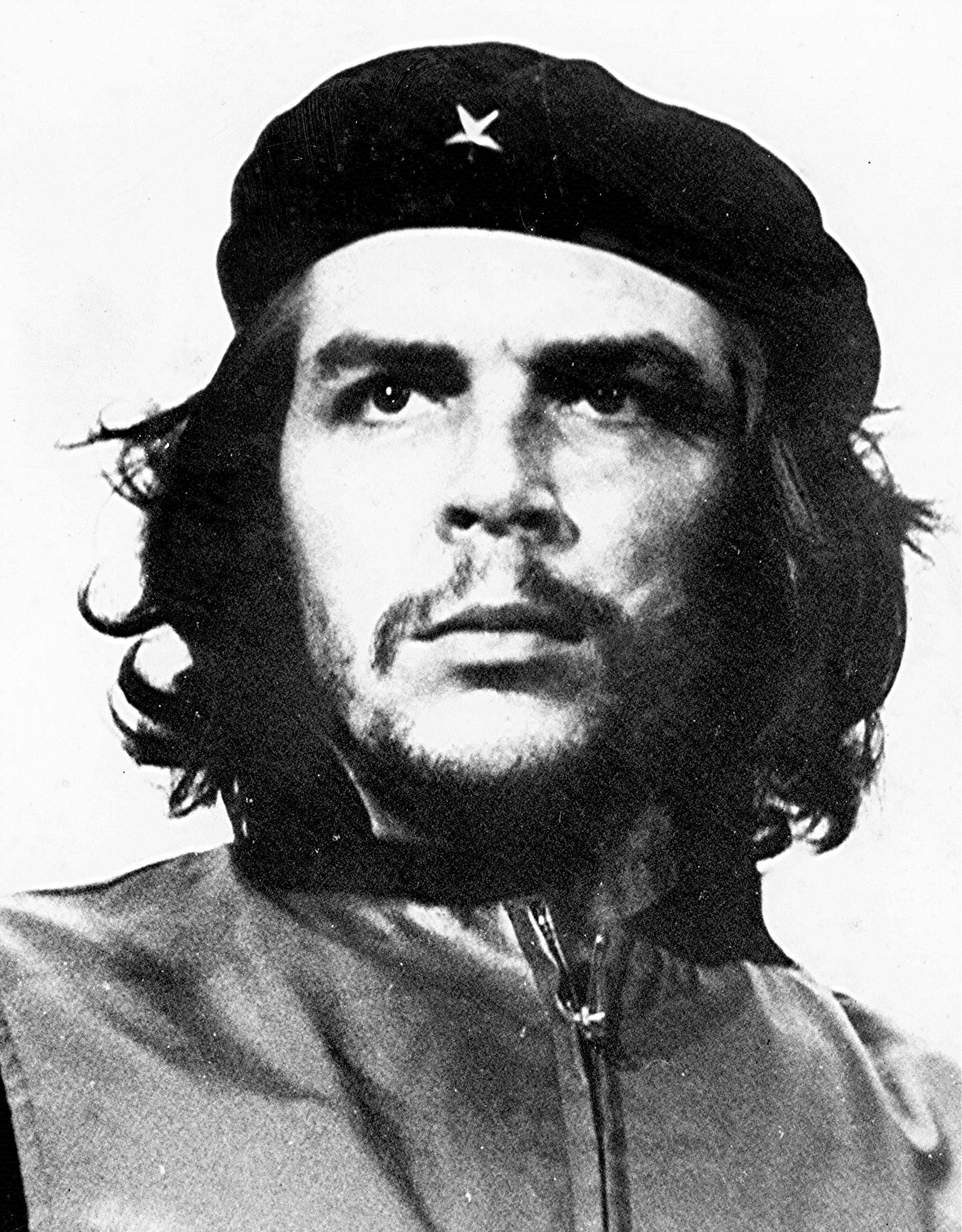

The Guerrillero Heroico or the “Heroic Guerrilla Fighter”, is an iconic photo of Che Guevara, an Argentine Marxist revolutionary from mid 1900’s Cuba.

Guevara fought for communism in Cuba, becoming a strong symbol of the revolution. He remains controversial because of the many extreme measures he took in this fight, despite being widely revered. This iconic picture of him was taken by Alberto Korda on March 5th 1960, during a funeral service for lives lost as a result of the explosion of a munitions freight boat.[1]

The photographer was, at the time, working for the Cuban newspaper Revolución. Koda explained that he was struck by Che Guevara’s powerful expression, a stare over the crowd that showed “absolute implacability”, anger and pain.[1] The newspaper never printed this photo in its coverage of the service, but Koda held on to the portrait in his own studio.[1]

It become “viral” in 1967 when Koda gave two prints to an Italian, who published it for the Cuban government. The photo then began to show up all over the world – particularly in magazines and newspaper, and then in popular culture, such as the colour poster done by Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick.[1]

Che’s later execution in October 1967 cemented his place in history, and this photo in particular would immortalize Che in popular culture too.[1] But I argue that the commercialisation of his image is itself evil, as it goes against the morals that he embodied.

The evil nature of commodifying Che

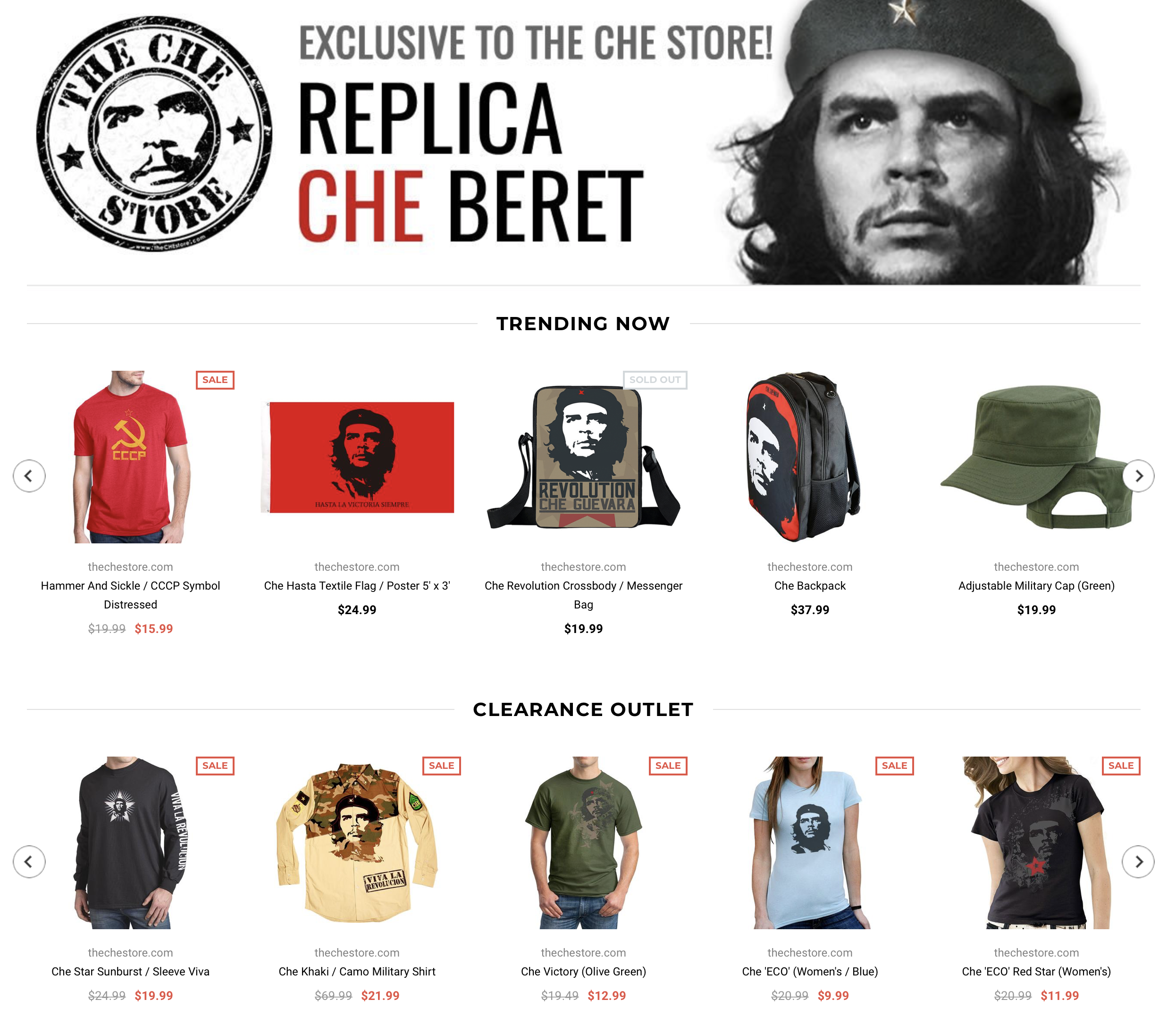

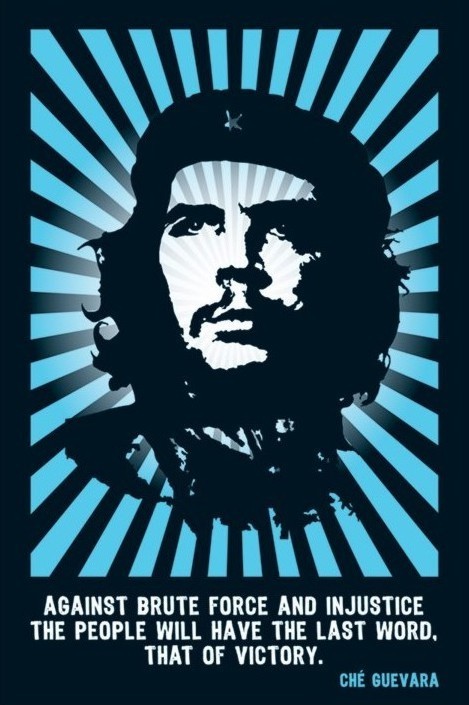

In popular culture Che Guevara’s face has become a symbol for “the power of individual expression”, reinforcing ideas of resistance to conformity and oppression.[2] These ideas resonated with many people and groups at the time, and continue to do so today. In fact, stylised as it often is into a stencil/pop-art look, as a cultural artefact the “Heroic Guerrilla Fighter” has become one of the most popular and marketable images of all time.

Screenshot of some of the merchandise available from www.thechestore.com, where as we can see Che Guevara’s image and other images of communism being used for profit.

Many (though not all) people may purchase these items because they share a degree of resonance with Che’s political philosophies. But the irony is that “Che would have used the royalties from any such commercial ventures to destroy the social and economic system that produced them”.[2]

The mass consumption of Che’s imagery, I believe, is reflective of what is termed “disordered capitalism”, a term used to describe how aspects of morality and politics are now intertwined with the commercial.[3] This is most observable is in the commodification of suffering, where “experiences of atrocity and abuse” have become highly profitable. This applies to the marketization of Guevara’s image primarily because his global profile occurred after his death – via execution. The significance and viral popularity, implicitly references this.

Che devoted his life to fighting against a capitalist system that in his view was significantly destroying the way of life of poorer people. As well as making money off his martyrdom to this cause, commodification of his image ignores the pain and suffering he endured through his revolutionary campaign while alive, and ignores the suffering of the people he fought for.

From an anthropological lens, this is also a case of global and local systems interacting. The image is consumed by global ‘fans’ and profited on by companies in many other countries. But the sale of his image undermines the political and ideological value that he has as a symbol to Cuban citizens in particular. The commodification of his image shows an attempt to disempower his communistic ideals.

In their analysis of suffering and its representation in media, Kleinman and Kleinman discuss suffering as “one of the existential grounds of human experience”.[3] But in a saturated media age, they argue that North American society has become de-sensitized to images of trauma.[3] Moreover many engagements with the suffering of others, via the media, are as part of a commodified system where cultural capital is gained through the presentation and circulation of trauma stories. So much so that complicated stories are reduced “to a core cultural image of victimization”.[3] Stories like Che Guevara’s become lost in an over saturation of his image, and other images of suffering – removed from context and significance, now bearing cultural and economic capital but losing moral and political potency.

A moral use of images

Frosh’s (2018) work on the way a sense of moral obligations can shape public interactions with stories and images of suffering, can help further unpack the complexities of commodifying and consuming Che Guevara’s image. In his study of Holocaust survivor testimonies, Frosh [4] reinforces that through the production and consumption of these testimonies through digital sites, individuals express and experience a “moral obligation to the past and to the dead”.

Can the same be said of Che Guevara? Should there not be a moral obligation to preserve the mindset and values of this deceased man? If so, should it be via consuming his image as a product, or by refusing to?

There are other reasons of course why this image may be rejected. Che is controversial because while he was viewed by a freedom fighter and hero by Cubans oppressed by the capitalist system of the time, he was also seen as a violent extremist and dictator: in the pursuit of revolution and freedom.

While there are many valid arguments against the man himself as, it is important to stress that even men perceived as evil can generate genuine love and admiration from people. Che is treated with and regarded as a Saint in some parts of the world due to his fight against oppressive and demeaning forces of capitalism – for example in Bolivia, where many worship him as “Saint Ernesto”, or in Cuba, where residents of Havana worship and pray to “Saint Che” by lighting a candle.[5]

As well as obligations to the dead, Frosh talks about obligations to the witness-survivor. In relation to Che Guevara, this could be examined in relation focused toward those that continue to praise and revere Che as a central part of their political ideology, and their real and personal history – in Cuba in particular, but also further afield.[4] This includes those who fought with him and for his cause, and continue to today. It includes intellectuals, workers and students.

We can apply Frosh’s idea to highlight a moral obligation to those living people connected to Che Guevara – those that remember and revere him. Including those Cubans that Che attempted to save as they were belittled and demeaned by an oppressive capitalist system. How would this additional layer of obligation be enacted, in our engagement with this image?

Concluding (and condemning)

Image retrieved from: https: //www.allposters.com/-sp/Che-Guevara-Posters_i1181_.htm accessed 8/4/19

Che Guevara was (and is) a controversial and influential figure. In examining the use of his image I have demonstrated the complexity of moral engagements with iconic political images such as this.

As a man he fought against capitalistic ideals, and has become a cultural icon. As a cultural artefact, his image on merchandise becomes a site of contention considering the moral obligations we not only have to the dead but also the living.

While debate about the evilness of Che the man remains prevalent, I conclude with the assertion that the capitalistic capture of his image for monetary gain is truly evil regardless.

References

[1] Meltzer, S. (2013). The extraordinary story behind the iconic image of Che Guevara and the photographer who took it. [online] Imaging-resource.com. Available at: https://www.imaging-resource.com/news/2013/06/06/the-extraordinary-story-behind-the-iconic-image-of-che-guevara [Accessed 11 Apr. 2019].

[2] McCormick, G. (1997). Che Guevara: The Legacy of a Revolutionary Man. World Policy Journal, [online] 14(4), pp.63-79. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40209557 [Accessed 26 Mar. 2019]. [64]

[3] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996). ‘The appeal of experience; the dismay of images: Cultural appropriations of suffering in our times.’ Daedalus, 125 (1): 1–24. [8; 1; 9; 10]

[4] Frosh, P. (2016) ‘The mouse, the screen and the Holocaust witness: Interface aesthetics and moral response’, New media and society. Sage Publications, 20(1): 351–368 [ pg.353]

[5] Lazo, O. (2016). The Story Behind Che’s Iconic Photo. [online] Smithsonian. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/iconic-photography-che-guevara-alberto-korda-cultural-travel-180960615/ [Accessed 11 Apr. 2019].

The Smell of Suffering: Portrait of a Street Boy

Written by Yi Li, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

Street photographers visualise social suffering through their artwork. They engage (themselves and us) with unfamiliar experiences: shrinking cities, strange portraits. Photographers can function as both moralists and anthropologists. They are often spectators, often self-exiles – presenting a version of evil for others to interpret, but often also fulfilling their own sense of moral obligation.

My argument is that both the positionality of the street photographer, and the medium of the photograph, means that photos sometimes break free from the time and space, conveying a universalism of personal adversity. I use an example of street photography of homeless in Moscow to discuss this.

Down and Out

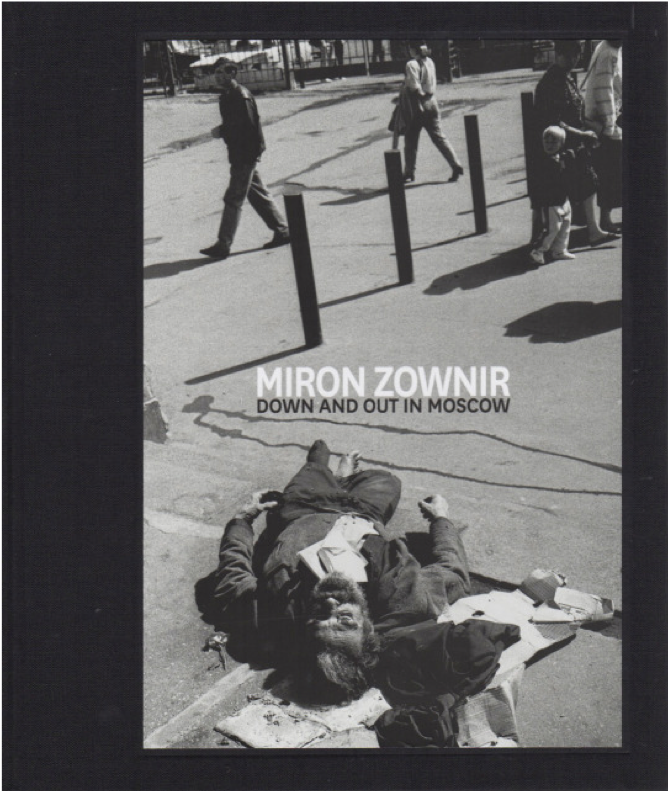

German photographer Miron Zownir is one of the most radical contemporary examples. His focus on marginal characters and the dark side of cities is rooted in his childhood. A Ukrainian-German who grew up in post-war Germany, Zownir as a teenager immersed himself in Eastern European literature without trusting any existing political systems or social stereotypes. His inherent interest in individualists inspired him to live in slum-like places, capturing streets with an anti-establishment attitude.

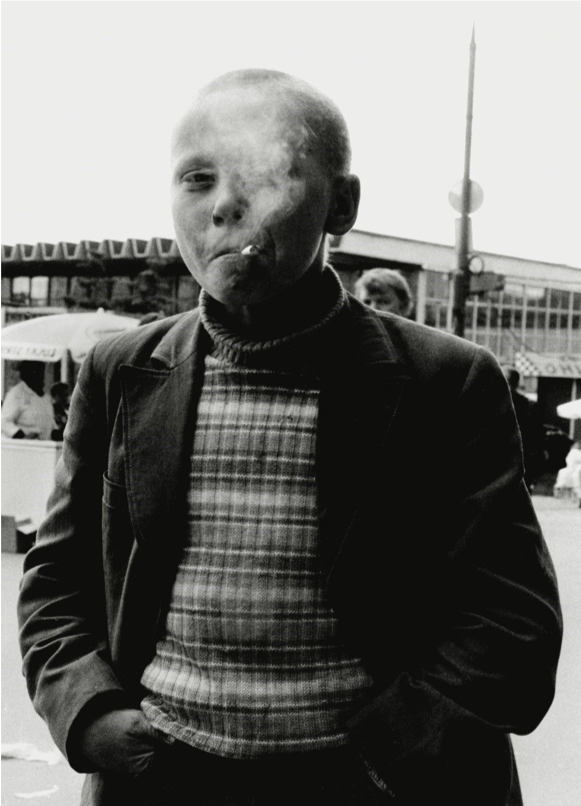

The street portrait is from Miron Zownir’s publication Down and Out in Moscow, a series of images that captured the homeless crisis in the Russian capital in 1995, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

I noticed the smoking boy with an adult expression to his cynical appearance when I first came across it in 2018. It is somehow different from the other challenging photos in his book. Momentarily, the encounter between Miron Zownir and the boy constructed a story about how individuals were abandoned by society. The diffusing cigarette smoke in front of the boy seems to allow me to smell the evil that permeated the city.

Kleinman & Kleinman (1996)[i] discuss the moral implications of photographs, through contextualising engagements within creators, audiences and images.

Zownir’s photographic experience runs through the technical transition: turning from black-and-white film to digital photography in the post-modern era. This photo was captured in a classic form, of black and white portraiture displayed in gallery spaces, and print journalism (books, and magazines). But it is worth noting that the extended agency of photographs can shift, depending on medium, from a momentary, regional realm to a worldwide standing discussion, through different forms of reprinting and representing.

How different would the viewers experience of this boy’s suffering be, scrolling past a small version in a social media feed? Touching his face on a tablet?

Moral Obligation in Street Photography: Unperceived Suffering as Social Experience

Anthropologists may ask: what is the basis of a photographer’s sense of moral obligation to take photos on streets?

Street photography concentrates on people and their behaviour in public, thereby also recording personal history: though without formal consent, and with the combination of spontaneity, outsider perspective, and private exploration. These subjects of circumstances are generally unaware – either stared at or ignored until they were documented. Street photography uses these collected narratives to define cultures or places, with no duty to serve a larger whole, and no limitation on how they reconstruct these places[ii].

Kleinman & Kleinman considered that photographers represent individual suffering as part of social experience, for others to access – whether these are extreme or ordinary forms of suffering. But as anthropologists, they caution that “there is no timeless or spaceless universal shape to suffering,” (1996, p:2).

In Down and Out in Moscow, Miron Zownir photographed death, sin, and a harsh lived reality. Underlying the powerless state, the rampantly violent proliferation pushed Moscow to become a hotbed of criminal forces in the 1990s; “the most aggressive and dangerous city, … people were dying right there on the street”.[iii] Such tension immediately changed Zownir’s original mission: to document Moscow’s nightlife with three-month project funding from a photographic committee.

Suffering is one of the existential grounds of human experience, and Kleinman & Kleinman suggest that moral witnessing also must involve a sensitivity to others, albeit with unspoken moral and political assumptions. Still functioning as a photographer, Zownir did not tend to query the government, or alter Moscow residents’ condition – but instead chose to live briefly in this shadowed twilight zone, to experience the nightmare.

Individual into the Universal: Reflexive Appreciation against the Silent Oblivion

How can we perceive a stranger’s suffering as universal? Here, a street boy’s sophisticated body language is beyond verbal expressions: dressing in a suit over a horizontal striped turtleneck sweater, his hands are hidden in his pants pockets like a social youth. He looks indifferent to the surroundings and unmoved by the photographer. He is clothed, unlike many beggars, and yet he was banished to a community where no-one had a home.

This portrait reminded me of the 1994 film In the Heat of the Sun. The film is based on Chinese writer Wang Shuo’s novel Wild Beast, which is set in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution, and tells how a teenage boy and his friends are free to roam the streets day and night in a period in which all the social and educational systems are extremely non-functional. Both protagonists are undergoing suffering – the film an example of the way their individual experiences can be abstracted and universalised, for the consumption of a wide variety of audiences. Yet this this also shows us how images and films can provide an insight into personal suffering that is usually invisible – although the harsh realities behind the lives they represent often go on unchanged.

The unwitting suffering of Zownir’s street boy is entangled with the political unrest in Moscow. But as a photograph, it also exists apart from the historical context: “a professional transformation of social life […] a constructed form that ironically naturalised experience.”[iv]

The frame itself cannot communicate this context. Yet it can communicate something else – the universality of human feeling event amidst diverse and ethically incommensurable [v] societies. Perhaps this is the power of portraiture – indeed the seminal psychological research of Ekman, and others, has asserted that emotional expression on faces is universal [vi] – meaning that moods and feelings may at times transcend cultural limitations, an idea often grappled with in the anthropology of emotion.

Conclusion: photography as a container of truth and imagination

Miron Zownir wrote in his poetry: When the earth returns with a thousand sunsets, the truth of the universal is darkness.[vii]

Photography blurs social facts, but seals emotions. Whether the boy would recognise the chaos, ignorance and madness that Zownir’s book communicates, in his free childhood in post-collapse Moscow, cannot be known. Yet seeing this photo as a cultural artefact, we can recognise that both the photographer and the audience as complicit in reproducing and politicising fragmented histories in photography. The photograph becomes a container for these forms of imagination.

Several years later after this photo was taken, when Miron Zownir was back in Moscow for his upcoming exhibition, the city’s exterior had been cleaned up. The silent responses of audiences standing in front of an enlarged version of this photograph, seemed at a vast remove from its original context. What meaning, what comfort, did it hold then? Yet the world still calls for images, as ‘the mixture of moral failures and global commerce is here to stay’ (Kleinman & Kleinman 1996: p. 7).

References:

[i] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[ii] Levy, S. (2019) ‘Street photography as a process’ in Lens Culture Guide to Street Photography, pp. 8-12

[iii] Zownir, M. (2014) ‘I was always an individualist’, Berlin Interviews, by Katerina, http://berlininterviews.com/?p=1375.

[iv] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[v] Fassin, D. (2009) ‘Beyond good and evil?: Questioning the anthropological discomfort with morals.’, Anthropological Theory. Sage, 8(4), pp. 333–344.

[vi] Ekman P, Friesen W (1976). Pictures of Facial Affect. Consulting Psychologists Press : Palo Alto.

[vii] Zownir, M. (2018) ‘Black’, Vision

A crash course on the anthropology of evil

Posted on by smisu13p

Dr Susan Wardell teaches a course called ‘The Anthropology of Evil’ (ANTH424). Last week she responded to the Christchurch mosque shootings with a twitter thread, drawing on course content to ask pointed questions about social patterns of sense-making in New Zealand, and in the media, in the wake of the attack. The full (19-point) thread is available in the link below, and also pasted as text below

https://twitter.com/Unlazy_Susan/status/1107760378694385664

Crash course: I teach a paper called ‘The Anthropology of Evil’ at

@Otago. It just got very real. This thread will unpack some ideas from the course in relation to the#ChristchurchTERRORISTattack. Questions, not answers.#anthropology#anthrotwitter#ChristchurchMosqueAttack [1]When the world is shattered, human meaning-making kicks in fast. We try to ‘locate’ evil within existing worldviews, including theological, secular, and academic. We collectively ask what/who/where, & WHY?! This gives us the social resources to assign blame, prescribe action. [2]

What is ‘evil’? An inherent quality of a person? Their intention/motivation? The action itself? The consequences of the action? Watch how the media and legal system frames this for

#ChristchurchTerrorAttack. And what about a white supremacist who has never committed violence? [3]What role can social scientists play in responding to the

#christchurchtmosque attack? Should we be thoroughly analysing moral topics, whilst bracketing our own views (Fassin 2009), or formally taking sides, being politically engaged (Scheper-Hughes 1995)#anthrotwitter [4]Does social science have a language appropriate to representing suffering? Is this thread itself unethical, in its stilted, theoretical removal from very real pain, grief, loss of the

#ChristchurchMosqueShootings? How should we analyse atrocity without being reductive, cold? [5]I’ve seen many posts arguing against learning the terrorists name and background because they don’t want to ‘humanize him’. It’s easy to create a ‘monstrous’ other. Monster = not human. But he is a human. That’s scarier to acknowledge. HE is us, as well as ‘they’ are [6]

The terrorist is described as ‘evil’.”‘Evil’ is part of the vocabulary of hatred, dismissal, or incomprehension” (Morton 2004). SHOULD we seek to understand the lives, worlds, & thinking of white supremacists? Are condemnation & understanding incompatible? [7]

#anthropologyHow are we fitting the story of the

#christchurchmosqueattack into existing, familiar narratives? What is the risk? Yesterday a student & I bet that we would soon see references to mental illness – a common narrative for white male violent offenders. Came true within hours. [8]What elements of news about the

#christchurchmosqueattack have affected you most? I’m going to guess it’s the images. Images are sometimes seen as a more authentic language for pain than words, but also function to ‘frame’ complex realities. Reflect on the ones you’ve shared [9]Kleinman (1996) warns that mass media circulation of images means suffering can be “remade, thinned out, distorted”. Susan Sontag saw photography as ‘predatory’. Let’s think about: who took the images and why? Who is sharing them, and why? Who is in them, and who isn’t? [10]

Frosh (2016) discusses digital morality: the cursor as a proxy moral compass. What do we click on, or watch, & why? A sense of obligation to ‘witness’ tragedy? Empathetic hedonism? (Recuber 2016, also see: https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/inplural/wp-admin/post.php?post=122&action=edit … ) What would it mean to NOT watch/view/click? [11]

Lots of discussion about what NOT to view (the manifesto, the livestream). Calls to give attention to victims, not perpetrator. We are exercising agency, within the ‘attention economy’ of social and mass

#media. Capital-driven systems, but with room for resistance. [12]What makes something or someone LOOK evil? How are particular features of particular bodies, coded as evil? Places and objects can also take on strong (through fluid) meanings, and emotions. What have mosques symbolised in NZ in the past? Now? What about the hijab? Guns? [13]

A typical terrorist tale involves a villain who has infiltrated a community, but is an outsider (Loseke 2016). Does the fact that the

#christchurchmosqueattack terrorist was an Australian, change how NZ will address its own racism? Do we still get to be the ‘goodies’? [14]How does hate come to circulate around specific people, bodies, or identity markers? Sara Ahmed (2004) writes is not not just part of ‘extremism’ and crime, but is a “product of the ordinary” Hate crimes do not just involve visceral power, but broader structures of power [15]

‘Banal’ evil refers to everyday, complicit, thoughtless evil (not sadistic malice). Is racism in NZ like this? Is racism part of ‘structural evil’: the longstanding formal (legal/bureaucratic/political) systems that discriminate and harm through their normal functionality. [16]

It’s through the cultivation of collective emotions that people come to FEEL, to BELIEVE in the imaginary social unit called the ‘nation’. In NZ’s past, who has been ‘othered’ to build a stronger sense of ‘us’? What does it mean to now say ‘they are us’, & is it enough? [17]

There has been talk about lack of Muslim voices even in the mainstream media coverage of the

#ChristchurchTerrorAttack. Testimony has a power not despite, but BECAUSE of subjective experience. When Muslims say they are shocked, broken, but not SURPRISED, are we listening? [18]Silence can help diagnose power. We must pay attention to silences, gaps in narratives, forgetting, vagueness, or selective remembering, about our own history, including the many instances where white supremacists acted publicly in NZ before this, as pointed out in a blog post by Catherine Trundle (an anthropologist from Victoria University, Wellington): https://bit.ly/2TIJ4Ti [19]

Posted in Curriculum and Pedagogy, Media/political commentary | Tagged anthropology, christchurch mosque shooting, Christchurch terrorist attack, evil, islam, media, othering, pedagogy, Social anthropology, teaching, terrorism | Leave a reply