The Smell of Suffering: Portrait of a Street Boy

Written by Yi Li, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

Street photographers visualise social suffering through their artwork. They engage (themselves and us) with unfamiliar experiences: shrinking cities, strange portraits. Photographers can function as both moralists and anthropologists. They are often spectators, often self-exiles – presenting a version of evil for others to interpret, but often also fulfilling their own sense of moral obligation.

My argument is that both the positionality of the street photographer, and the medium of the photograph, means that photos sometimes break free from the time and space, conveying a universalism of personal adversity. I use an example of street photography of homeless in Moscow to discuss this.

Down and Out

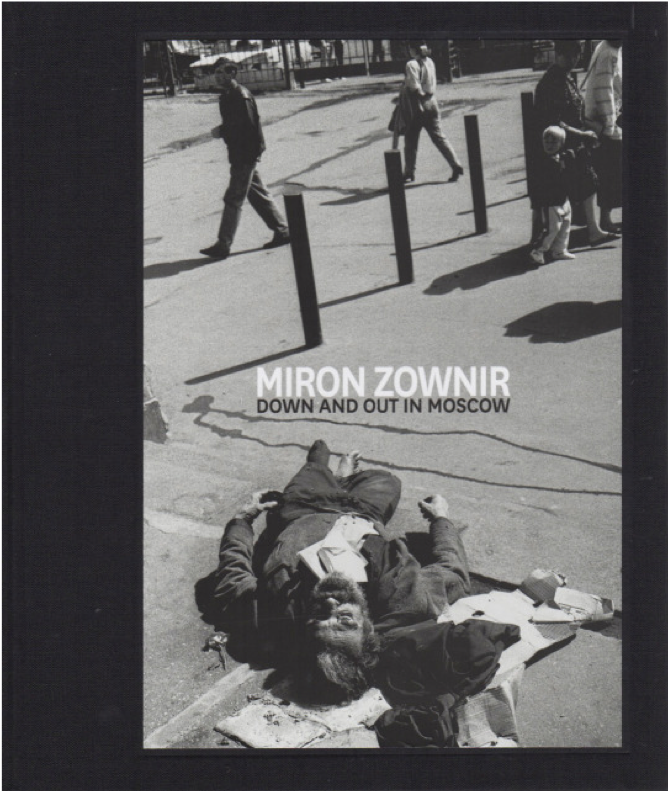

German photographer Miron Zownir is one of the most radical contemporary examples. His focus on marginal characters and the dark side of cities is rooted in his childhood. A Ukrainian-German who grew up in post-war Germany, Zownir as a teenager immersed himself in Eastern European literature without trusting any existing political systems or social stereotypes. His inherent interest in individualists inspired him to live in slum-like places, capturing streets with an anti-establishment attitude.

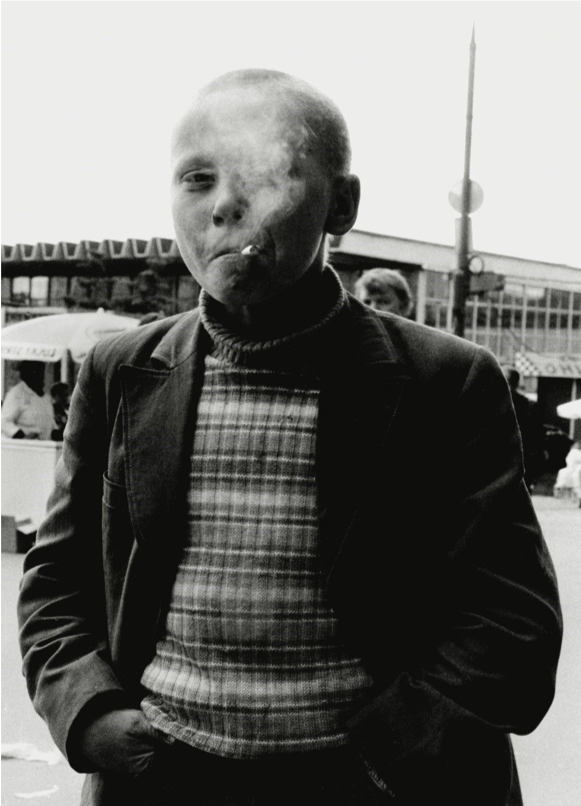

The street portrait is from Miron Zownir’s publication Down and Out in Moscow, a series of images that captured the homeless crisis in the Russian capital in 1995, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

I noticed the smoking boy with an adult expression to his cynical appearance when I first came across it in 2018. It is somehow different from the other challenging photos in his book. Momentarily, the encounter between Miron Zownir and the boy constructed a story about how individuals were abandoned by society. The diffusing cigarette smoke in front of the boy seems to allow me to smell the evil that permeated the city.

Kleinman & Kleinman (1996)[i] discuss the moral implications of photographs, through contextualising engagements within creators, audiences and images.

Zownir’s photographic experience runs through the technical transition: turning from black-and-white film to digital photography in the post-modern era. This photo was captured in a classic form, of black and white portraiture displayed in gallery spaces, and print journalism (books, and magazines). But it is worth noting that the extended agency of photographs can shift, depending on medium, from a momentary, regional realm to a worldwide standing discussion, through different forms of reprinting and representing.

How different would the viewers experience of this boy’s suffering be, scrolling past a small version in a social media feed? Touching his face on a tablet?

Moral Obligation in Street Photography: Unperceived Suffering as Social Experience

Anthropologists may ask: what is the basis of a photographer’s sense of moral obligation to take photos on streets?

Street photography concentrates on people and their behaviour in public, thereby also recording personal history: though without formal consent, and with the combination of spontaneity, outsider perspective, and private exploration. These subjects of circumstances are generally unaware – either stared at or ignored until they were documented. Street photography uses these collected narratives to define cultures or places, with no duty to serve a larger whole, and no limitation on how they reconstruct these places[ii].

Kleinman & Kleinman considered that photographers represent individual suffering as part of social experience, for others to access – whether these are extreme or ordinary forms of suffering. But as anthropologists, they caution that “there is no timeless or spaceless universal shape to suffering,” (1996, p:2).

In Down and Out in Moscow, Miron Zownir photographed death, sin, and a harsh lived reality. Underlying the powerless state, the rampantly violent proliferation pushed Moscow to become a hotbed of criminal forces in the 1990s; “the most aggressive and dangerous city, … people were dying right there on the street”.[iii] Such tension immediately changed Zownir’s original mission: to document Moscow’s nightlife with three-month project funding from a photographic committee.

Suffering is one of the existential grounds of human experience, and Kleinman & Kleinman suggest that moral witnessing also must involve a sensitivity to others, albeit with unspoken moral and political assumptions. Still functioning as a photographer, Zownir did not tend to query the government, or alter Moscow residents’ condition – but instead chose to live briefly in this shadowed twilight zone, to experience the nightmare.

Individual into the Universal: Reflexive Appreciation against the Silent Oblivion

How can we perceive a stranger’s suffering as universal? Here, a street boy’s sophisticated body language is beyond verbal expressions: dressing in a suit over a horizontal striped turtleneck sweater, his hands are hidden in his pants pockets like a social youth. He looks indifferent to the surroundings and unmoved by the photographer. He is clothed, unlike many beggars, and yet he was banished to a community where no-one had a home.

This portrait reminded me of the 1994 film In the Heat of the Sun. The film is based on Chinese writer Wang Shuo’s novel Wild Beast, which is set in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution, and tells how a teenage boy and his friends are free to roam the streets day and night in a period in which all the social and educational systems are extremely non-functional. Both protagonists are undergoing suffering – the film an example of the way their individual experiences can be abstracted and universalised, for the consumption of a wide variety of audiences. Yet this this also shows us how images and films can provide an insight into personal suffering that is usually invisible – although the harsh realities behind the lives they represent often go on unchanged.

The unwitting suffering of Zownir’s street boy is entangled with the political unrest in Moscow. But as a photograph, it also exists apart from the historical context: “a professional transformation of social life […] a constructed form that ironically naturalised experience.”[iv]

The frame itself cannot communicate this context. Yet it can communicate something else – the universality of human feeling event amidst diverse and ethically incommensurable [v] societies. Perhaps this is the power of portraiture – indeed the seminal psychological research of Ekman, and others, has asserted that emotional expression on faces is universal [vi] – meaning that moods and feelings may at times transcend cultural limitations, an idea often grappled with in the anthropology of emotion.

Conclusion: photography as a container of truth and imagination

Miron Zownir wrote in his poetry: When the earth returns with a thousand sunsets, the truth of the universal is darkness.[vii]

Photography blurs social facts, but seals emotions. Whether the boy would recognise the chaos, ignorance and madness that Zownir’s book communicates, in his free childhood in post-collapse Moscow, cannot be known. Yet seeing this photo as a cultural artefact, we can recognise that both the photographer and the audience as complicit in reproducing and politicising fragmented histories in photography. The photograph becomes a container for these forms of imagination.

Several years later after this photo was taken, when Miron Zownir was back in Moscow for his upcoming exhibition, the city’s exterior had been cleaned up. The silent responses of audiences standing in front of an enlarged version of this photograph, seemed at a vast remove from its original context. What meaning, what comfort, did it hold then? Yet the world still calls for images, as ‘the mixture of moral failures and global commerce is here to stay’ (Kleinman & Kleinman 1996: p. 7).

References:

[i] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[ii] Levy, S. (2019) ‘Street photography as a process’ in Lens Culture Guide to Street Photography, pp. 8-12

[iii] Zownir, M. (2014) ‘I was always an individualist’, Berlin Interviews, by Katerina, http://berlininterviews.com/?p=1375.

[iv] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[v] Fassin, D. (2009) ‘Beyond good and evil?: Questioning the anthropological discomfort with morals.’, Anthropological Theory. Sage, 8(4), pp. 333–344.

[vi] Ekman P, Friesen W (1976). Pictures of Facial Affect. Consulting Psychologists Press : Palo Alto.

[vii] Zownir, M. (2018) ‘Black’, Vision

Fire and Flood: Grounding disaster, trauma, and emotion

I recently read Sociologist Timothy Recuber’s (2016) book, Consuming Catastrophe: Mass Media in America’s Decade of Disaster. It is a great book, and I loved it particularly for acknowledging that media is not just informational, but involves aesthetic and performative cues for emotional response. Recuber draws on case studies of 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina, among others. His writing is specific to the USA and acknowledges its scope as such.

I recently read Sociologist Timothy Recuber’s (2016) book, Consuming Catastrophe: Mass Media in America’s Decade of Disaster. It is a great book, and I loved it particularly for acknowledging that media is not just informational, but involves aesthetic and performative cues for emotional response. Recuber draws on case studies of 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina, among others. His writing is specific to the USA and acknowledges its scope as such.

As an Antipodean social anthropologist, I am struck by the need for a cross-cultural and de-centred lens on these topics. There is space for ethnographic studies that highlight the locally situated nature of disaster and disaster-response – the way the narratives, symbols, words and meanings that make sense of catastrophes around culturally grounded and particular,

Black Saturday: reviewing art on the anniversary of disaster

Last week I attended a talk by Dr. Grace Moore, called ‘The Art of Recovery’. Before moving to Otago’s English Department, Dr Moore worked with the ARC (Australian Research Council) Centre for Excellence for the History of Emotions, her research focussing on fire in Australian historical writing and art. But timing and location meant her response also engaged heavily with the devastating Victorian bushfires of ‘Black Saturday’, in 2009. On this 10-year anniversary of the event, she presented some pieces from a collection of art created by survivors.

Last week I attended a talk by Dr. Grace Moore, called ‘The Art of Recovery’. Before moving to Otago’s English Department, Dr Moore worked with the ARC (Australian Research Council) Centre for Excellence for the History of Emotions, her research focussing on fire in Australian historical writing and art. But timing and location meant her response also engaged heavily with the devastating Victorian bushfires of ‘Black Saturday’, in 2009. On this 10-year anniversary of the event, she presented some pieces from a collection of art created by survivors.

William Strutt’s oil painting ‘Black Thursday’ (1861). Referencing the largest fires ever recorded in Australia, taking place in Victoria 1851.

Dr. Moore’s work makes some fascinating comparisons between this, and 19th century European colonists’ narratives and paintings of bushfire. As such she has been able to highlight some of the moral frameworks and social relationships (i.e. heroism, mateship) that have made sense of bushfires in a culturally-specific way. She notes also that there is a rich tradition of depicting fire among many indigenous Australian communities, which would beg deeper research.

The connection between Moore’s talk and Recuber’s book struck me, in that both addressed representations of disaster (and its aftermath), and also that both discussed the role of emotion and affect as they circulated through particular mediums of communication.

Emotion and trauma: inside, outside, on the page and screen

In Dr. Moore’s talk at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, art was framed as something used to ‘confront’ and ‘work through’ trauma. It is ‘cathartic’, and ‘therapeutic.’ The vested interest in such processes, after trauma, is not entirely individual. Amidst controversy about accountability and the inadequacies of long-term support, Grace noted the investment of local government in programmes that allow people to ‘channel their emotions’.

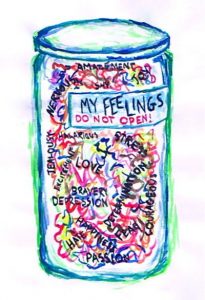

I could also say a lot here, from an anthropological perspective, about the culturally-grounded metaphors of emotion that this all relies on, and in particular the hydraulic metaphors of emotion. These are central to psychodynamic frameworks that emphasise the destructive potential of un-expressed (‘bottled up’) emotions, and the moral and therapeutic values of sharing (‘venting’) emotion.[i]

I could also say a lot here, from an anthropological perspective, about the culturally-grounded metaphors of emotion that this all relies on, and in particular the hydraulic metaphors of emotion. These are central to psychodynamic frameworks that emphasise the destructive potential of un-expressed (‘bottled up’) emotions, and the moral and therapeutic values of sharing (‘venting’) emotion.[i]

I have also written about the distinction between ‘channel’ and ‘vessel’ metaphors of emotion.[ii] In this case I think it is the intersubjectivity of affect that the frequent appearance of ‘channel’ metaphors hint at. They highlight art as not only a personal process but a relational one, a channel for survivors to connect with other people who were not present, across what is often framed as an ineffable void of experience.

Image from the DAX Centre. Source: http://castlemaineart.com/artists/konii-c-burns/konni-c-burns-dax-centre/

Alternatively perhaps the art itself is the vessel, the receptacle, which holds the emotion channelled into it. Indeed Moore noted that emotion and memories are “embedded” into the work. Regional exhibitions focussed on ‘Recording and Collecting Black Saturday’ and the longer-term efforts of DAX Centre to collect these works (and others by victims of broadly-defined ‘trauma’) could be analysed through this lens. It certainly opens up some interesting questions:

- Do these paintings and sculptures represent the materiality of suffering?

- What then, is the political or moral impetus to hold it and preserve it? To communicate it? To view, experience, or consume it?

There is considerable work still to be done examining the ‘moral economy’ of disaster communication: in mass media, and social media. Recuber’s book includes some particularly interesting work on the ‘digital archives’ that formed around the 9/11 and to Hurricane Katrina. It occurs to me that these, and the exhibitions and collections Dr Moore on, can be seen as a deliberate (and ‘high culture’) institutionalisation of the spontaneous shrine that is increasingly a mark of postmodern collective grief.[iii]

Drawing close to the flame: Empathy and its limits

Recuber talks about the ‘aura’ disaster has; the ‘haunting traces of the real’ that it leaves (p16, 26, 90). Are these possible ways to understand the social practice of collecting and preserving ‘trauma’ art?

Recuber’s idea of ‘empathetic hedonism’ also recalls itself here– “in which the desire to understand the suffering of others is pursued doggedly, through always necessarily unsatisfactorily.” (p9).

Recuber notes particular kinds of ‘stylized and idealized’ empathy evoked by mass media coverage of disaster in the contemporary USA (p19). Once again I believe comparative attention to locally situated forms of empathetic engagement in other places would be beneficial. There are undoubtedly some differences, for example, between the capitalist performative merchandise Recuber describes around the Virginia UniTech Shooter, and the patterns of charity, volunteerism, and witnessing/spectatorship specific to Black Saturday.

Stories (including Dr Moore’s own) of watching weather changes in nearby cities create what appears to me to be a distinctive, embodied, and locally-grounded experience of witnessing, mediated by the sight, smell, and taste of smoke.

In examining art made by children’ affected by the Black Saturday bushfires, Moore also poignantly highlighted the way their experience was often mediated by windows – in cars, as they fled, or in schools where they lived with constant view of devastation after the event. Windows featuring in art are indicative of “intensity, shielding, seeing” she points out. This alludes to a bigger question in the communication of catastrophe – the value (and risk) of seeing. Of empathy itself. The question of vicarious traumatisation.

In my own work with youth workers in Canterbury, after the Christchurch quake, metaphors not only of vessels and channels, but also of boundaries, were common in the stories of care, emotional labour, burnout and compassion fatigue I recorded.

Moore’s talk, I noted, included art by one psychologist who counselled survivors of Black Saturday and framed her art around experiences of “emotion oozing red and sad”. The ‘contagion’ model of emotion is heightened when it is extremely traumatic circumstances in question.

Sometimes keeping the channels, the windows, ‘open’ is experienced as dangerous, overwhelming, even when there appears to be a moral imperative to do so. Other times the desire to draw closer to disaster seems to overcome the distance that is safety. But all of these responses occur in situated local worlds – with their own history, their own geography, and their own socio-political contexts, as Recuber and Moore variously highlight.

In emphasising context and comparison, the anthropological lens has value here too. I am eager to see more work that ‘grounds’ disaster, and the communicative practices it generates, in this way.

Written by: Dr Susan Wardell

References:

[i] Lutz, C., White, G.M., 1986. The Anthropology of Emotions. Annual Review of Anthropology 15, 405–436. https://doi.org/10.2307/2155767

[ii] Wardell, S., 2018. Living in the Tension: Care, Selfhood, and Wellbeing Among Faith-based Youth Workers. Carolina Academic Press.

[iii] Magry, P. & Sanchez-Carretero, C. (2007) ‘Memorializing Traumatic Death’, Anthropology Today, 23(3): 1–2.

The suffering of war, the eye of the beholder

Posted on by smisu13p

A post written by Samuel McComb, for an ANTH424 assignment on ‘visual images and the communication of suffering and evil’.

I love art. Creation in different forms has provided me with an outlet where nothing else can, and exposed me to works that have not left me to this day. Some I have carried lightly, while others remain as haunting as the first time I laid eyes on them.

One particular image has remained with me in a way others have not. It sits clearly in my mind’s eye. Without demanding focus or derailing the bustle of other thoughts, it simply reminds me of its presence with a whisper – “I’m still here”. For years I have held space for it, maintaining an uneasy truce. Decontextualized, it could do no harm nor be put to rest. But upon its most recent resurgence I felt compelled to understand more. I could not have predicted how thoroughly this discovery would challenge my perception.

Witnessing

My familiarity with this image harks back to my high school years. I was around 16, or perhaps 17, and in the midst of what one might describe as a period of healthy teenage angst, channelled and encouraged by an art department with an affinity for the grunge aesthetic. A plastic skeleton lived in the corner of the art room. The gift of a perfectly mummified cat (found when a neighbour’s house was relocated) received promises of “Excellence” grades for the year’s NCEA assessments. One lunchtime, two friends and I made the plastic skeleton a cardboard house, in the middle of the classroom. It was in this environment that our subject matter would be deconstructed, remade and distorted as we explored our theme; War.

Paul Frosh (2016), a media and communications researcher with the Department of Communication and Journalism at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, made a strong argument that our ability to respond morally when witnessing suffering is shaped by how we view it – the medium used in its portrayal changes how we engage our senses. His conclusions are drawn from an analysis of user experience with Graphical User Interfaces (GUI’s) of smartphones and computers when viewing Holocaust survivor testimonies . These provided clear examples of how the experiences and actions we take when witnessing suffering shape our response.

Frosh then considered the moral obligations of the viewer when witnessing and responding to suffering. He divided these responses into three types: attention, engagement, and action. This was a useful framework within which view my own interactions with, and responses to, suffering, and specifically to explore how this raw image (fig.1) became the work I presented in my high school art folio (fig.3).

Attention

As I began my project, I was searching for images and shapes that represented an idea or a feeling. I first saw the soldier while shuffling through a stack of photocopies collected from old books and internet searches. These photos of medals, memorials, soldiers and statues had been carefully selected by the teacher to help us explore our theme. I recall that several images had been ripped by other students fighting for the ‘cool’ pictures – the ones with the biggest guns – by the time I began my search.

On one level these were just raw materials, no different to any other aesthetic resource provided by the teacher. Yet just as Frosh (2016) argued that how we access depictions of suffering plays a major role in our responses, the way I was searching for images shaped my response. I was holding history between my fingers, taking just enough time to gain some perspective of the content as I shuffled through the photocopies, before passing the stack of unsuitable pictures to the boy beside me. I could almost forget the reality behind the paper as I traced shapes overtop of figures, the smooth monotony of the paper interrupted by creases and rips as I thought of textures and colours to represent what I felt each copy contained. After the preliminary search, every raw image was subject to a deeper focus – I wanted to know what aspect of each photo captured my attention.

Action

Once we have seen suffering we are faced with a moral decision in how we respond. I could choose to ignore what I saw and felt in the image of this young soldier. I could choose another image, another topic to explore – my resulting artwork would have been displayed in the same way, to the same audience, regardless of the content. I could have found more images of big guns, but I didn’t. I needed to share what I had seen and felt.

Frosh (2016) describes the primary response to suffering in the digital age as communicative action – sharing a video or photograph widely, to raise awareness and prevent further actions, or simply to acknowledge that the suffering occurred. Sitting in my classroom, I needed to share what I had felt when I saw my soldier – the destruction of innocence that does not choose a side, the shared suffering inflicted on humanity through war. In this case though, sharing was not the quick click of a digital button, but a belaboured process of interpretation and creation with paint.

Sometimes we can choose to filter or curate our media feed, hide from the suffering before it overwhelms us. As in social media, so too in art we can choose to cover what we don’t want to see and focus on brighter times. Indeed Frosh (2016) makes clear there is the potential, when communicating enormously tragic events, for individual stories to be lost and the narrative of suffering to become overwhelming; the viewer becoming helpless and unable to respond morally to all they are exposed to. Reflecting on my folio (fig.3) certainly could elicit this response, I have to now reflect, as the young soldier becomes one small feature within the whole composition, one piece of a larger picture.

For a moment the viewer too feels the overwhelming weight of suffering that exists behind the barrier of our screens, and we become like my soldier, or perhaps the photographer – left with nothing but the ability to witness and remember.

Revelation

I never tried to find out more about the photographs I used at the time, nor in the ten years since I made this board. I knew the wars they came from, perhaps who they fought for, but not the stories of the men. In hindsight I was hiding from the full truth, keeping the distance of ignorance to keep from being overwhelmed. The folio received an Excellence, and placed second in my school that year, yet I have been almost ashamed to share it knowing so little about the history of my source materials. The most recent time my soldier whispered, I listened, intending at last to let him rest.

To my surprise it turns out the soldier who inspired my art, who has stayed with me for so long, was a work of fiction – filmmaker Berhnhard Wicki’s own moral response to suffering. My soldier’s photo was in fact a still from his film “Die Brücke”. Released in 1959, this West German film follows a group of seven 16 year old school students enlisting late in 1945. The film shows their experiences as they are sent to defend a bridge in their home town with almost no training, and all but one of the boys die as they experience the horrible reality of war. The film ends noting that it was based on a true story (IMDB, 2020).

Several things suddenly made sense when I found this out. Firstly, the affinity I had felt was real because the soldier was my age. Secondly, everything had been designed to elicit an emotional response from the viewer – camera angle, posture, positioning. I wondered if it was a sense of difference that made my soldier’s photo stand out among the stack – subconscious awareness that it was somehow wrong, or staged. But I soon realised that did not matter.

The intent of Die Brücke was to share an emotional response to the horror of war. More than fifty years on it continues to do so with just one frame. In doing so it continues to offer me a choice of moral action – turn away from the suffering, or witness it, and share a moral response of my own. The eye of the artist may say “This is Not a Soldier”, but through the eye of the beholder we can still say “This is Suffering”.

Sources:

Frosh, P. (2016). The mouse, the screen and the Holocaust witness: Interface aesthetics and moral response. New Media & Society, 20(1), 351–368.

The Bridge. (1959, October 22). Retrieved April 10, 2020, from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0052654/

Fig.1 Source: Teeuwisse, J. H. (2017, March 3). NOT a photo of German child soldiers at the end of WW2. Retrieved April 2020, from https://www.flickr.com/photos/hab3045/33231024585/in/photostream/

Fig.2 Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Treachery_of_Images Retrieved April 2020

Fig.3 & Fig.4: My own work, photographed April 2020

Posted in ANTH424 (Anthropology of Evil), Case study, Media/political commentary | Tagged ANZAC, art, cultural anthropology, Digital, film, moral anthropology, morality, peace, Social anthropology, soldier, visual anthropology, war, witnessing, WWII | Leave a reply