Stories, Songs, and Survival: the role of narrative in slave religion

Posted on by smisu13p

Written by: Meena Al-Emleh.

[Adapted from an essay written for ANTH228/328: Anthropology of Religion and the Supernatural]

Preacher detail dhs spet. 1874 p. 463 congregation. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jimsurkamp/33698015396/

African American culture has been described as a narrative culture[i]. Gospel churches in particular are examples of the strong cultural ties between storytelling and Black spiritual identity. This narrative tradition did not begin with the conversion of enslaved Africans to Christianity, however. Rather it was formed as Christian traditions were actively fused with deep-rooted narrative traditions from diverse African peoples.

If we examine how this took place, we can see that the religion that came to be practiced by slaves during the Antebellum period was characterised cultural adaptation. The narratives at the heart of this religion played a key role in negotiations of memory, pain, and fractured cultural identities and beliefs. They created conceptual spaces where community and autonomy could be asserted, and new identities developed.

So how exactly did stories achieve all of this?

Context and cultural change

The context from which ‘slave religion’ grew is complex – the term itself given by religious scholar Albert Raboteau to the varied Christian-adjacent religious practices among new-world slaves.

The first African slaves were brought to the ‘New World’ in the early 17th century. They were uprooted from their entire social worlds – moved around and sold without any regard for their tribal and linguistic relations, nor family ties. Slavery was a systematic eradication of culture, selfhood, and humanity, which in many ways constituted a “social death” for slaves[ii].

While much was lost in this process, plantation life did not fully erase slaves’ cultures. Instead many living traditions were carried with people into their new lives, and adapted to fit the new social and spiritual frameworks presented to them. Many slaves were from tribes in West and Central Africa, and as they lived and worked together, these shared beliefs and experiences developed into a “quasi-African worldview.”[iii]

Louis Armstrong Park, New Orleans. A plaque reads: “During the late 17th century and well into the 18th centuries. slaves gathered at Congo Square on Sundays and sang, danced, and drummed in authentic West Aftrican style. This rich legacy of African celebration is the foundation of New Orleans’ unique musical traditions, including Jazz.” Sculpture by Adewale S. Adenle, dedocated April, 2010. Photo October 9, 2014 (by Kent Kanouse).

On plantations in North America, slaves came into contact with Christian concepts and biblical stories, and many individuals and communities responded to these. Yet they were often excluded from the actual institution of Christianity by racist ideologies that held them as ‘soul-less’ and therefore exempt from salvation[iv]. Because of this, many of their own religious meetings were held in secret[v]. These were spaces where the complexities of slave life could be negotiated, and where new communal identities could begin to develop[vi].

Folktales and the forging of new identities

One key form of narrative for African slaves in the Antebellum era, was the folktale. Folk stories brought from Africa did not remain static, but changed alongside the tellers’ social contexts – an active negotiation of social life occurring in the telling.

Call-and-response was a prominent feature of oral storytelling – a style originating in West and Central Africa, and heavily encouraging group participation[vii]. Cortazzi believes that in typical oral narratives, the audience’s cultural positionality and beliefs are reinforced by the singular teller[viii]. As call-and-response is driven by the whole group rather than a single storyteller, it offers group-driven communal positioning. In this way the folklore functioned as a counter to the dislocation of slavery, as together slaves could develop new shared systems of understanding.

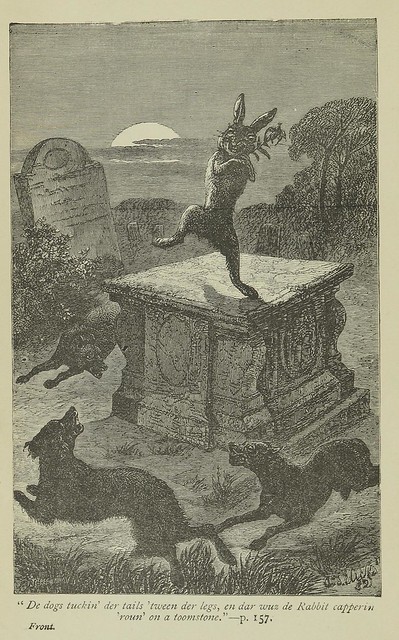

Uncle Remus, or, Mr. Fox, Mr. Rabbit, and Mr. Terrapin, 1891 (circa). Mr Fox is another example of a trickster character, in a moral tale. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/43021516@N06/20712823746/

Records of popular characters and scenarios in Antebellum era folk tales show an integration of Christian concepts into African stories. For example, the Devil portrayed in these tales bears a closer resemblance to the trickster of West African folklore than the explicitly evil Satan within Christianity[ix]. As is seen in the stories of ‘how Jack beat the Devil’ and ‘how John married the Devil’s daughter’, the Devil is a figure who makes deals for your soul through mischief, and who is ultimately beaten by a cultural hero with similar trickster qualities[x].

The main characters jump in and out of expected roles, according to the demands of the situation, deploying patterns of behaviour like shamming, silence, and masking to stay alive. This parallels the lived cultural reality of the enslaved people who participated in the telling. It also provides a narrative space for the formation of new identities and world views – distinct from either white Christian, or African identities, and yet more complex than a simple blend of the two.

The ‘Negro Spiritual’: songs of suffering and deliverance

Another narrative form that took shape within religious slave communities is that of the ‘spiritual’ – Christian songs created to emphasise particular Christian values and express the pain of slavery.

The traditions of musical speech and musical selfhood in this context is intrinsically African, as it draws from the tonal languages and antiphonal music of these slaves’ ancestors[xi]. Like stories they often used call-and-response styles to involve the whole group. The songs are thought to have emerged creatively between the musicality of the preacher and the “talk back” of the congregation[ii] – a specific mode of song-speech.

The spirituals also repositioned the communal narrative of these antebellum-era slaves, as a narrative of deliverance. They frequently supplanted the Old Testament story of the Children of Israel with their own narrative of captivity, positioning them within a long history of survival stretching back to Moses. The theme of deliverance and a focus on a hopeful future are key in the lyrics. For example the spiritual Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel? which says: “Didn’t my Lord deliver Daniel, an’ why not-a every man.”[xiii]

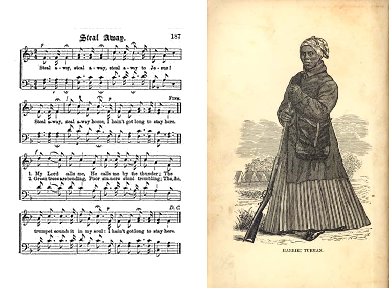

“Steal Away to Jesus” was a song allegedly used by Harriet Tubman (pictured) to announce to potential freedom seekers that she was going to lead people out of slavery. The drawing of Harriet Tubman courtesy of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Source: http://www.actaonline.org/content/revolution-song-healing-through-negro-spirituals-glides-womens-center

Survival was central, but also resistance. Spirituals reminded people that survival depended on collective strength. They also became a messaging tool among emancipationist conspirators, who reworked the songs with new, secret references to escape routes, meeting times, and safe houses[ii].

This way of coding messages had close roots in folklore traditions – a technique frequently used by protagonists in trickster stories. In this way, spirituals acted as both a literal and figurative way to share and protect new African-American ways of being.

Conclusions on narrative, identity, and culture

Enslaved Africans in the Antebellum United States used narrative, in its many forms, to gradually unify memory, traditions, beliefs, and cultural changes into a communal identity. As such the narratives central to ‘slave religion’ became a way of protecting themselves against the spiritual violence enacted on them by the system of slavery – the loss of place, connectedness, and identity.

Cortazzi asserts that “Narrative […] is a discourse structure or genre which reflects culture.[viii]” However in this this context, narrative did more than that: it shaped the future of a people by reflecting not just what the culture was, but also what it needed to be.

References [i] Tolagbe Ogunleye, “African American Folklore: It’s Role in Reconstructing African American History.” Journal of Black Studies 27 no. 4 (1997), 16; Waldo F. Martin Jr., “The Sounds of Blackness” In Upon These Shores: Themes in the African-American Experience 1600 to the Present, ed. William Scott & William Shade (London: Routledge, 2013), 254. [ii] Luke Powery, Dry Dem Bones: Preaching, Death, and Hope (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2012), 19-50; 23; 60 [iii] Steve Vaughn, “Making Jesus Black: The Historiographical Debate on the Roots of African-American Christianity.” Journal of Negro History 82 no.1 (1997), 28. [iv] Jon Sensbach, “Slaves to Intolerance: African American Christianity and Religious Freedom in Early America” In The First Prejudice: Religious Tolerance and Intolerance in Early America, ed. Chris Beneke & Christopher Grenda (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 204. [v] Charles Orser, “The Archaeology of African-American Slave Religion in the Antebellum South” In Southern Crossroads: Perspectives on Religion and Culture, ed. Walter Conser & Rodger Payne (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2008), 45. [vi] Edward Pavlic, Crossroads Modernism: Descent and Emergence in African-American Literary Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), 7-8. [vii] Wallace D. Best, Passionately Human, No Less Divine: Religion and Culture in Black Chicago, 1915-1952 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2005), 98. [viii] Martin Cortazzi, Narrative Analysis (London: Routledge, 2014), 167-193; 168. [ix] David Murray, Matter, Magic, and Spirit: Representing Indian and African American Belief (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), 58. [x] Zora Neale Hurston, Mules and Men (New York: Harper Collins, 2009). [xi] Albert Raboteau, Slave Religion: the Invisible Institution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 52. [xiii] David Spener, We Shall Not Be Moved: Biography of Song and Struggle (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2016), 33.

Posted in Case study, Undergrad coursework | Tagged African-American, Antebellum, anthropology, Christianity, culture, faith, identity, Narrative, plantation, religion, Slaves, solidarity, songs, spirituality, stories, United States | Leave a reply

Speaking to Socks: An Anthropologist gets KonMari-ed

Posted on by smisu13p

Marie Kondo’s 2014 book, which was a #1 New York Times Bestseller, is reaching new fame through a Netflix TV series in 2019.

Three years ago, I (an anthropologist, feminist, mother, and wife) bought a book. The book was The Life Changing Magic of Tidying.

I read it. I loved it. I sorted my entire house and started folding things for the first time in years. Then I tucked the book into the far corner of a bookshelf and quietly kept folding.

Now suddenly it is cool, and I can come out of the (miraculously tidy) closet as a fan of Marie Kondo.

An image of my husband’s socks and undies drawer, which I ‘Kondo-ed’ last weekend. Am I a bad feminist, or a good wife? No idea, but it sure was satisfying. NB. Marie recommends folding socks and storing upright… ‘balled up’ socks are angsty socks!

On the electric updraft from the Netflix ‘Tidying up with Marie Kondo’ special, there has been a frenzy of decluttering across New Zealand. There are reports of op-shops closing under a flood of donated goods. Kitchens cupboards across the country have never been so organised. Garages have never seemed so spacious. Folding is at an all-time high.

Having run out of drawers to tidy myself, I thought it was time to put on my anthropology hat for a moment and ask: Does this craze mean anything? What is it about a small cheerful Japanese woman who speaks to socks, that is also resonating so deeply in the USA, and NZ, at this moment?

Decluttering the context: gender, class, and the ‘spirit’ of things

Let’s be clear, there is a gendered component to this trend: and I’ll admit the amount of thought I give to stratagizing about the organisation and maintenance of my home gives me mixed feelings as a feminist. The burden of both physical and mental labour to do with the house is typically female. There is also a classed component: the ability to buy, the types of things we buy, and how we view material possessions in relation to both identity and security, in socioeconomic categories and inequalities. Not to mention where and how we are housed. It’s fair to view the success of KonMarie as a largely middle-class female phenomena.

It is interesting too though, how a method that in many ways relates to Asian apartment-style living became so successfully exportable to the USA, NZ, and many other western nations. The geographic component seems no obstacle, but is there a something deeper: a cultural component? And how does it translate?

It seems to me that Marie’s method draws on distinctly Japanese (or at very least, non-European) ways of seeing the world. Particularly what could be broadly called ‘animism’, which is a belief in the aliveness, the ‘essence’ of both sentient and non-sentient things. Animism allows that animals, trees, rocks, mountains, rivers… and yes, socks… all have a ‘spirit’.

This approach to paves the way for a holism that sees our material life as entangled with our own physical, spiritual, and social wellbeing and success.

“What I’d like you to remember as you go through this process is that you’re not alone, the house itself and all your belongings are there to support you and go with you” – Marie to recently-widowed Margie (from ‘Sparking Joy after a loss: episode * in ‘Tidying Up with Marie Kondo’ (Netflix 2019).

So I’m interested to ask now more than ever: in the traditionally dualist or materialist ‘West’, what is drawing us to (or driving us to?) this more animist way of understanding material life?

Joy! (and the dogs of dread on its heels)

Marie Kondo’s central mantra is to surround yourself with only things that ‘spark joy’. Doesn’t that sound delightful? But I think it’s uptake makes most sense when we recognise that material things in many people’s homes, in their amount if not their nature, sparks not joy but shame, anger, dread and exhaustion.

A relatively small pile compared to some of the mountains features in the Netflix show. Image source: https://www.today.com/series/one-small-thing/life-changing-magic-tidying-testing-marie-kondos-method-t21356

Indeed the ‘pile it all up’ part of Marie’s method is designed to confront, and motivate. It certainly highlights the troubling excesses of capitalist consumer society (though that is hopefully news to no-one). This is where the Netflix show grabs me. Watching the mothers, the widows, the retirees – their struggle, their suffocation. Then eventually, their relief.

Honestly I am myself light-years from being a minimalist, before OR after Marie Kondo upends my home. In fact it is the persistence and constancy of clutter in my life brings, it’s crushing weight, that most draws me to KonMari.

One of iteration of memes emerging around Marie Kondo. Source: https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/1447776-tidying-up-with-marie-kondo

I believe that the way ‘we’ (middle-class folk in developed countries) experience this material crisis of clutter in our homes is in its own way, as an existential crisis. I think that the frustration and paralysis about stuff, and what to do with it, goes far beyond being a practical concern. Rather it embodies deep uncertainties about moral ways of living and being; of relating between both present and absent family members; of reconciling past, present, and imagined futures, in our homes and our lives. It is in this context that KonMari method appears as such a shining salvation… a gently charted path (with a cheerful guide) through a minefield of shame, uncertainty, and kitchen appliances.

Certainly when I think about it, it’s not the meaningless-ness of the stuff in my home that bothers me, it’s its meaningfulness. In fact it makes me question the taken-for-granted connection between materialism and individualism. So much of the stuff that entangles us is not because of any innate qualities of the things themselves. It’s not only stuff we bought, but stuff we were given. Stuff we inherited, or hope to pass on. Things that represent who we were, or who we want to be. Things we like to show off, things we want to forget are even there. It’s about social relationships, and identities, memories and hopes and connections. It’s not really material at all. Or individual.

The KonMari method simply lets us acknowledge that. It asks us to feel that, in fact – intimately, as we hold each item in our hands. It reminds us that our homes and our possessions have a history: a social quality and an experiential one. Why not call it a ‘spirit’? Why not speak to it when we want to make a change? It might just work, and here is why…

Why it works: Ritual, emotion, and behaviour

Ritual is a powerful tool for dealing with emotion, and it is sprinkled all throughout the KonMari method: Greeting a house. Feeling a casserole dish. Waking up piles of books. Thanking a pair of socks.

Rituals by definition are actions that carry shared meaning. But they don’t just solidify existing meanings – they can also change them. Rituals are often used to transition things (and people) between different categories. So even a small moment of saying ‘thank you’ to used items can make it easier to mentally move them from the category of ‘possession’ to that of ‘donation’ or ‘trash’, which in turns makes it easier to change our behaviour towards it. To let it go. This works for items we keep as well – rituals of holding, feeling joy, and even folding can and do have the ability to change and how those items will be treated and experienced by their owners.

As an avid second-hand shopper, my wardrobe has always been particularly out of control, but I enjoy my clothes more now not only because I have less and can actually see them in the wardrobe, but because I value them more. They don’t just have functional value, but each one is deliberately chosen, treasured. I find I also think twice before I buy more because I know and value what I have. Also when I do farewell an item I can recognise what it has already given me, rather than feeling guilty.

In this way the KonMarie method is not ‘anti-stuff’ at all. Quite the opposite… it teaches a love, connection, and attachment to material life that seems antithetical to goals of decluttering, but isn’t. It opens a space that paradoxically begins to bring an almost hedonism, to minimalism – but one distinct from the excesses of consumerism.

Marie Kondo. Image source: https://i.cbc.ca/1.4972060.1547065914!/fileImage/httpImage/image.jpg_gen/derivatives/16x9_780/marie-kondo.jpg

When a drawer closes, a window opens…

A summary of these brief anthropological thoughts would be this: Emerging from a Japanese context, the KonMari method is somehow also a timely response to western existential crises of clutter (that are moral, as well as material). Yes it is practical, but it is more than that.

With a persistent cheer and a handful of quiet rituals, Marie is opening a small window in the stuffy room of western rationality. Her methods let us acknowledge our relationship to places and things at the level of affect and being. To both hold on, and let go, with joy.

- Dr. Susan Wardell (‘Incorrigibly Plural’ editor, Lecturer in Social Anthropology, also found on Twitter)

Posted in Media/political commentary | Tagged animism, anthropology, capitalism, consumerism, decluttering, gender, housekeeping, Japan, KonMari, Marie Kondo, materialism, minimalism, New Zealand, religion, Ritual, spirituality, tidying, USA | Leave a reply

Healing the Self: Motivational Speakers as Shamans

Posted on by smisu13p

Written by: Emma Gamson

[Adapted from an essay written for ANTH228/328: Anthropology of Religion and the Supernatural]

Motivational speaking is a category of verbal performance where the goal is to inspire or motivate an audience 12. Motivational speakers tend to share self-narratives, to convey messages of hope, reassurance and success 8. There is no training or certification required; success depend on an individual speakers’ popularity 8, 9.

Tony Robbins is a highly influential motivational speaker whose messages focus on empowerment, self-transformation and “unleashing the inner-self” 14, 7.

Tony Robbins presents his talk ‘Why We Do What We Do’ at the February 2006 TED conference. The image shows Robbins open and powerful stage presence as he addresses as audience. Source: https://www.ted.com/talks/tony_robbins_asks_why_we_do_what_we_do

This post analyses some of Robbins’ performances, to argue that motivational speaking can be understood as a type of healing practice. I apply concepts from the anthropology of religion, such as liminality, communitas, and ritual, to understand how he frames the self, how he establishes legitimacy, and how he enacts healing.

Narrating your self into (a new) existence

Understandings of the ‘self’ varies cross-culturally. Greek philosophers Plato, and later Descatres, as well as much of early Christian thought, supported a dualist view of the person, in which the body is a physical, mechanical and matter of science, and the mind (in which the person or ‘self’ resides) is non-physical, spiritual and a matter of the church 16, 17. Conversely, Freud, Foucault, Sartre and Social Sciences have supported a non-dualism in which the self is made up of a body and mind immediately connected to each other, and both are subject to the influence of society and power 16. In anthropology, the ‘self’ is typically associated with the perception of one’s own existence, and is different to ‘identity’, which is more related to how ones existence is placed in relation to others 17.

Robbins uses narrative to convey themes of self-renewal, self-help and power of a true inner self, all of which he claims are controlled by state of mind and worldview 2, 15. His key argument is that “you can sculpt the person you want to be with whatever raw material you have available, so long as you acknowledge the early forces that shaped you” 15.

Processes of self are not just about the mind, but about the body too. In anthropology, embodiment theory emphasises the intimate connection between mind, body and culture (in in fact seeks to challenge these as separate categories, all together). Many motivational speakers also take a holistic view, including Tony Robbins, who treats the mind and body as distinct, but directly influencing each other 15.

Religion, ritual, and self-transformation

Ritual practice is a key feature of religion. Rituals can work to express meaning, and apply religious worldviews to daily life 11. Religious worldviews can form the framework against which individuals develop and create their self-narratives. Religious ritual deeply embeds this frameworks through embodied (implicit) and explicit knowledge of one’s self in the context of the world, consequently influencing how one perceives and acts in the world 11.

Tony Robbins on stage at one of his ‘Unleash the Power Within’ seminars. A three-and-a-half-day event oriented towards helping “you unlock and unleash the forces inside you to break through your limitations and take control of your life”. The image is a snapshot showing Robbins enthusiastic and big gestures that are incorporated into his stage performances. Source: https://www.tonyrobbins.com/events/unleash-the-power-within/

As a motivational speaker, Tony Robbins employs embodied, ritualized action in a way similar to religious practice. His talks verbally lay out a worldview in which individuals have an ‘inner power’. Then his rituals make this true by enacting the ‘unleashing’ of this power with bodily action 8, 15, 14.

Specifically, Robbins his audience to participate through verbal agreement 2, 15. Their vocal articulations are a ritual way of unleashing this power. By getting his audience to respond through an embodied ritual of call-and-response, in his talks and seminars, he is asking them to reposition their own self within this worldview; to re-write their self-narrative according to that. In shifting the framework for their story, he shifts the story and thus the self.

Why does ritual work? Hot coals and big crowds

The effectiveness of Robbin’s performance is contingent on his audience. Religion is a dynamic product of human activity that tends to revolve around a central source of legitimacy or authority, but this must be continuously performed, negotiated, reproduced and validated by participants and audience members 1.

A seminar attendee calmly walks across a path of hot coals, embodying the beliefs and ideas that have been taught by Robbins. Behind cheers him on as they people queue for their turn. Source: http://morewealthandhealth.com/tony-robbins-fire-walk-review-read-fire-walk/

Robbins continuously negotiates and reinforces his authority when he prompt action from the audience. For example, Robbins created a ritualized action of walking over hot coals to show the power of the inner self, which many people have attempted 15. The offer would be absurd if the audience did not reinforce and embody support by actually attempting the walk, thus continuing to reinforce and legitimize the authority of Robbins and his worldview.

One key feature in the effectiveness of motivational speaking, is liminality. Anthropologists understand liminality as an intermediary stage in a ‘rite of passage’ ritual, which typically focuses on shifting someone’s social positionality. Like most motivational speakers, Robbins does indeed emphasizes ‘transformation’. We can argue that he uses his events to create a liminal space in which the possibilities for transformation occurs.

Communitas can be experienced in ‘coming of age’ rituals, rock concerts, sports games, prisons, religious events, and more.

The liminal stage is the ‘in between’ stage, and when lots of people are experiencing this together, it can lead to a state called ‘communitas’. Communitas is a state of anti-structure, where usual social boundaries and identities temporarily fall away, and people feel joined by bonds of common feeling 18. Liminality and communitas can both facilitate, acute moments of self-transformation.

Despite the perception of motivational speaking as an ‘individualistic’ form of healing, communitas appears to emerge again in ritualised acts in which Robbins’ audience participants respond collectively, rather than individually 18. After all, would it work the same if we was alone in a room with someone? His seminars can become a space of communitas – the audience all are temporarily separated from their normal lives, and united with others in their intense experiences in that room. It is together that they are remade.

Healing: is Tony Robbins a shaman?

People attending Tony Robbins talks seek empowerment. It is fair to infer then that they come with some sense of deficiency or disempowerment – while their bodies may be healthy, their ‘self’ is in need.

Religion is one framework of meaning that can help individuals make sense of what it means to have or to lose health, what it means to be lacking or whole10. While not a religion, Robbin’s talks similarly offer a framework of meaning that locate the cause of problems, and their solution, within a particular set of symbols and ideas: i.e. about ‘inner power’ and how to ‘unleash it’, and what effects (on both body and mind) this can have.

A shamanic healing ceremony, showing the jhākri (Nepali shaman) alongside a woman undergoing the healing process. Behind is a group who are also participating in and supporting the ritual (Sidkey 2010, p219)

There are similarities in particular with the way Toby Robbins works, and what anthropologists have observed of some shamanic traditions. For example, Yolmo shamans define health by the aesthetics of balance, wholeness and harmony to determine health 4. These values are embodied in the daily life of Yolmo society, embedding them in the body and shaping sensory experiences of health 4, 5. Shamans may conduct rituals involving trance states with vivid imagery to deal with illness such as soul loss 4, 5. This process not only relies on the action of the shaman themselves, but also through the participation of everyone present, including the patient 4, 5. This exemplifies the dynamic relationship between the authority of the religious healer, the participants and the social embodiment of values as key in making sense of the process of healing.

Tony Robbins seems to define health as a unity between how one lives their life and the cultivation of the power of their inner-self to create fulfilment and wellbeing. For example, in a video Robbins guides Rechaud, a 30-year-old man with a stutter, through a ritualized process of searching through memories for a cause of the stutter and bringing out Rechaud’s ‘inner warrior’ 13. Rechaud emerges ‘healed’ from his stutter and delivers a speech at one of Robbins seminars, acting as a symbol of success for this method of healing, which generated intense emotional responses from the crowd 13.

A stock image under the word ‘healing’. Source: pixabay.com

As with the Shamanic trances, Robbins guides Rechaud through a ritualized process of self-narrative that taps into imagery embedded in memories and in the symbol of the self as a ‘warrior’, to transform Rechaud and unify his inner self with his physical body to overcome the stutter.

Conclusion:

Motivational speakers in Anglo-American nations are not unlike shamans in a variety of other cultural settings – they are a culturally sanctioned form of (non-biomedical) healer, with accepted social authority. In observing Tony Robbins’ techniques, we can see how he uses this authority to lead audiences through rituals that facilitate a shift in self. His motivational seminars become a liminal space in which people are taken through a process of re-making their own narratives according to the framework he lays out, and thus are able to heal body, mind, and ‘self’.

References

Posted in Case study, Media/political commentary, Undergrad coursework | Tagged anthropology, authority, communitas, embodiment, healing, health, liminality, motivational speaking, personal growth, religion, Ritual, self, self-narrative, selfhood, shaman, shamanism, Tony Robbins, wellbeing | Leave a reply