Dawn Raids: the terror of racism in 1970’s NZ

Written by Amy Hema, for an assignment on ‘administrative evil’ in ANTH424.

The 1970s saw some of the darkest times for New Zealand, following the economic crash of the late 1960s. With the first waves of unemployment since the Great Depression, the country was looking for someone to blame. It was was in this context that ‘overstayers’ were deemed to be burden to New Zealand [1]. These overstayers were typically Pasifika peoples who had been actively recruited for New Zealand’s booming labour market, in the early 60’s. Now their deportation was deemed a priority.

To this end in 1974 the New Zealand police began raiding houses suspected of containing overstayers, in the early hours of the morning [2]. These came to be known as the Dawn Raids. Racially motivated, and traumatising for the Polynesian population that were often the focus, this is a moment in the country’s history that largely goes undiscussed, and yet had significant impact on a people group that were marginalised, villainised and targeted by the New Zealand government and police.

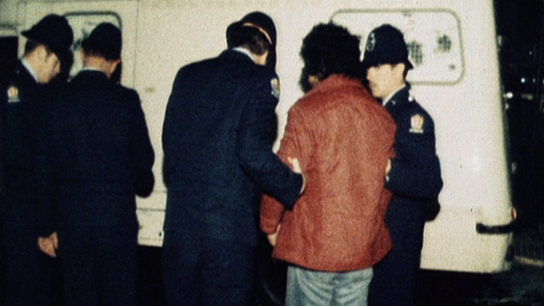

A screenshot from a 2015 ‘NZ on Screen’ documentary called ‘Dawn Raids’. The image shows a Pasifika man being taken into custody by police. The documentary represents very recent attempts to acknowledge this part of New Zealand’s history. Source: https://www.nzonscreen.com/title/dawn-raids-2005

Adams and Balfour have written extensively about the relationship between administration and evil; a relationship that is often overlooked, but powerful in enforcing ‘evil’ in the sense of harm against a particular vulnerable group [3]. The Dawn Raids are a prime example of administrative and bureaucratic authority being used to enact this harm.

Discourses of Dehumanisation

Adams and Balfour argue that our daily lives are built upon are taken for granted assumptions; that we take little time to examine the way we are living and the impact it may have. Subsequently, something as fundamental as language and storytelling can make us susceptible to participating in evil without realising it[3].

The dawn raids went largely unopposed by the general public due to the language and discourse used to describe those being targeted in the raids, being unthinkingly accepted.

In a 1975 campaign run by the National Party, Polynesians were depicted as aggressive, unwelcome pests who were taking jobs away from deserving Kiwis [4]. The ad told the story of New Zealand as a peaceful nation, one that you would want to raise your children in… until the arrival of immigrants. It claimed that these immigrants became incensed by the lack of jobs, healthcare and education, and turned angry and violent.

In these ads, the blame was being placed squarely on Polynesians; the happy compliant residents depicted were white, whilst the angry individual was brown with a large afro. As such, these ads were used to create a divide between ‘us’ and ‘them’ – those who deserved to be in NZ and those who did not.

The ads created a strong and specific narrative that became a taken for granted ‘Truth’; that Polynesians were taking advantage of New Zealand’s resources and generosity, and that they needed to be removed. Referred to simply as ‘overstayers’, ‘illegals’, and ‘browns’ and presented to the public as over-the-top caricatures, a clear message was sent about who these people were, what they were doing to the country and how they should be dealt with[5]. These catch-all terms enable the individual to refer to a group without acknowledging they are individual humans, who came to New Zealand looking for a better life, instead they are just a collective problem.

In interviews taken at the time of the raids [5], New Zealanders were clearly holding tight to these narratives. As such, they became participants in evil – accepting and condoning through acceptance that a group of people be harmed by prejudicial policies and laws. Standing back and watching it happen.

Through social discourse one can readily observe the way in which language is used to dehumanise and separate the other to allow for the continuation of administrative evil – by actively reinforcing racial stereotypes, create to separate and privilege, New Zealand citizens became passive participants.

The Social Construction of Compliance

In the case of administrative evil, there are hierarchies. Specifically, there are the policy makers and the enforcers. Since the policy makers are a few steps removed from the site of violence, they are able to distance themselves from the reality of the situation. The enforcers however are on the ground, and are active participants.

Interviews with former police officers evidence the same position; they may have been overzealous in their attempts to identify and charge overstayers, but they believed their cause was just, and they were following orders[5]. Adams and Balfour have discussed these attitudes in what they call ‘the social construction of compliance’ – in which the an individual is pushed to perform violence under the direction of authority – whether or not they agree with the process becomes irrelevant as they are no longer acting as an individual but as a cog in a machine.

Adams and Balfour argue that as a culture that has come to place so much value on individualism, the USA has come to expect that when presented with a difficult choice, an individual will stick to their morals and refuse to comply[3]. Did the normative ‘Pakeha’ 1970’s New Zealand share a similar moral system? We know from the overzealous policing that during the dawn raids, the police force became aggressive in their pursual of overstayers. They stopped individuals on the street and asking for identification, in what was essentially ‘stop and frisk’, since the individuals stopped were done so based on the colour of their skin. They raided homes at the crack of dawn, deliberately when individuals and families were vulnerable.

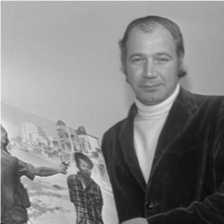

A New Zealand police officer on Lambton Quay, in 1975. Source: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/crime/80132822/decades-investigating-darkest-crimes-does-not-dent-top-detectives-optimism?fbclid=IwAR0gWhk-M76ykJswrlncS8Rsgz4TT6-krw44NeDlEA1LNJ_5jBqvUq6948g

The actions taken by the police and the legal system were extreme, and individuals were being persecuted for minor crimes (such as petty theft) to the fullest extent of the law, at an unprecedented rate – though this was all technically legal, functioning within the system rather than as an exception to it.

Policy makers and police officers put their own opinions and feelings aside to carry out the policies set in place – even if it meant brining harm by enforcing racist ideologies. Whilst there was some push back on the stop and frisk policies, they were ultimately widely enacted by law enforcement[5]. What one can observe from the police tactics at the time is that group morality had the capacity to overrule individualism – a fact not readily embraced by many who believe in individualism.

Concluding Thoughts

Women performing at a Pacifica conference in 1975. Source: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/women-together/pacifica

What is made evident by examining the history of the Dawn Raids in New Zealand, is that administrative evil relies on both passive and active participation. By sharing narratives of harmful individuals who are taking away jobs from more deserving individuals, and upholding policies that allowed law enforcement to act on racism and stereotypes, a culture was created that allowed evil to continue in a way that was accepted by the mainstream populace.

Adams and Balfour stress that administrative evil flourishes under conditions in which people believe in the cause or adopt the ideologies as taken for granted facts – the success of administrative evil then rests in the failure to identify the evil nature of the act until it’s too late.

References

[1] ‘Dawn Raids’. nd. http://dawnraidsnz.weebly.com/

[2] New Zealand History. ‘The 1970’s. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/the-1970s/1976

[3] Adams, G. & Balfour, D.L. (2014). Unmasking Administrative Evil: the dynamics of evil and administrative evil. Sage Publications.

[4] Te Ara (1975) ‘National Party Election Campaign Ad’ https://teara.govt.nz/en/video/2158/national-party-advertisement

[5] ‘NZ/Samoan Dawn Raids’ Documentary New Zealand. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZviIkSxjV0k

The execution of politics: how one photo of a Viet Cong prisoner shaped the war

*Trigger warning: Violent image*

I came across this particular image during my own personal exploration into global politics following World War II, in an online article about American politicians. I was shocked after reading into the caption, to find that in this image the man is already dead, with the bullet either still passing through his head, or having just passed through it.

I find this attitude towards this extremely violent situation quite striking. Even with an understanding that extensive exposure can lead to stoicism, it is intriguing to me that one can

I find this attitude towards this extremely violent situation quite striking. Even with an understanding that extensive exposure can lead to stoicism, it is intriguing to me that one canBy capturing and conveying suffering through visual imagery, the photographer becomes a witness of death, but also a moral actor. Adams believed two people were killed in that instant, “the general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera”6.

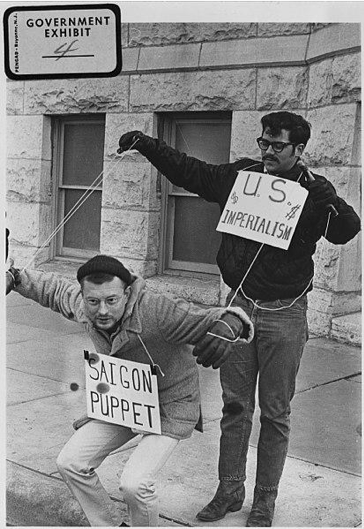

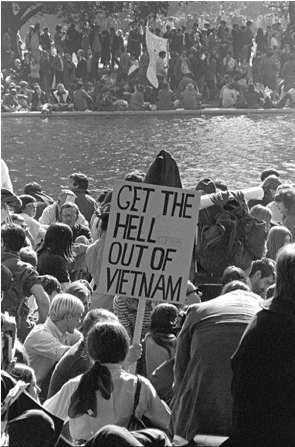

Mobilising Support for Social Action

Kleinman and Kleinman5 emphasise that visual representations of evil can be used to promote social action. Indeed this image slowly became an icon for American activism, and to this day serves as a reminder of the atrocities that arise from political conflicts. This photo was a “classic instance of the use of moral sentiment to mobilize support for social action”. A fellow Vietnam War photographer, David Hume Kennerly, put it this way: “I don’t know that it ended the Vietnam War, but it sure as hell didn’t help the cause for the government – one thing I know for sure, anybody who’s ever seen that photo has never forgotten it”.6

Kleinman and Kleinman5 emphasise that visual representations of evil can be used to promote social action. Indeed this image slowly became an icon for American activism, and to this day serves as a reminder of the atrocities that arise from political conflicts. This photo was a “classic instance of the use of moral sentiment to mobilize support for social action”. A fellow Vietnam War photographer, David Hume Kennerly, put it this way: “I don’t know that it ended the Vietnam War, but it sure as hell didn’t help the cause for the government – one thing I know for sure, anybody who’s ever seen that photo has never forgotten it”.6

The image was used to give a glimpse into the reality for those enduring such brutality, and conveyed a powerful intimacy and desperate message to the people of the USA. It is still considered in the USA to be the “Photo That Changed the Course of the Vietnam War”1.

Appropriating Suffering

This image meant that the death of the Viet Cong prisoner would not go unremembered. As Astor says, “this last instant of his life would be immortalized on the front pages of newspapers nationwide”1. However Kleinman & Kleinman5 also discuss how the suffering depicted in an image can be taken advantage of, particularly in the way that it is distributed and consumed. As is stated in their article, the use of an image to ‘right an inhumane situation’ can be inhumane in itself.

The image of suffering above was used by the American anti-war effort to serve a purpose; as a tool in the process of stopping the Vietnam War, but at what cost? The image may have succeeded in saving many lives by cutting the war shorter, however, the insensitive use of the image was disastrous for some.

For the victim’s wife, Nguyen Thi Lop3, the image served a very different purpose than it’s anti-war role in the US. For her, the use of the image played the role of messenger: informing Nguyen of her husband’s death. In a clip years on, Nguyen is recorded saying in Vietnamese that “a friend of mine brought me the newspaper and then I found out what had happened to my husband”.

The reproduction of this image did not allow this widow the privacy or respect that she deserved. It shows lack of understanding, respect and permission required in the distribution of material. Furthermore we can argue that to share the intimate destruction of human life with such a level of triviality (as glancing past it in a newspaper) de-sensitizes, and reduces from the pain of the victim. Kleinman and Kleinman explain:

“Suffering ‘though at a distance,’ is routinely appropriated in American popular culture, which is a leading edge of global popular culture. The globalization of suffering is one of the more troubling signs of the cultural transformations of the current era: troubling because experience is being used as a commodity, and through this cultural representation of suffering, the experience is being remade, thinned out, and distorted”.5

One effect of this, they argue, is the erasure and distortion of the importance of social experiences of suffering. In this case, the image itself can not inherently convey the contextual political systems that produced it; its literal content is simply a violent act between two individuals. Yet re-contextualised as part of the anti-War effort, it did serve to highlight wider political contexts, such that the social response to the image led to not only condemnation of the violent act by that one soldier, but a change in public attitudes towards US involvement in Vietnam, and eventually a shift in political decisions by the US.

Conclusion

Visual depictions of suffering can be used to make us aware of the suffering experienced in other parts of the world. These visual depictions have the potential to be used as a tool to support social movements. However, the use of images does have its limitations and concerns, transforming the intimate suffering of real people into a tool. It is still up to debate whether this is an acceptable price for social change, and who gets to drive the production and circulation of such images, what they mean, and for what purpose.

References

- Astor, M. (2018, February 1). A Photo That Changed the Course of the Vietnam War. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/01/world/asia/vietnam-execution-photo.html

- Watson, A. M. (2015). PULITZER PRIZE PHOTOGRAPHY: SAIGON EXECUTION. Retrieved from http://www.newseum.org/2015/05/12/pulitzer-prize-photography-saigon-execution/

- VIETNAM: VIETNAM WAR ANNIVERSARY: MEDIA (2). (2000).. Retrieved from http://www.aparchive.com/metadata/youtube/3061fe038ddb4dece288d433331d7b91

- Adler, M. (2009). The Vietnam War, Through Eddie Adams’ Lens.All Things Considered. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2009/03/24/102112403/the-vietnam-war-through-eddie-adams-lens

- Kleinman, A. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1–23. Available at: https://ezproxy.otago.ac.nz/login?url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027351. ISSN: 00115266

- Ruane, M. E. (2018, February 1). A grisly photo of a Saigon execution 50 years ago shocked the world and helped end the war. Washington Post. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/02/01/a-grisly-photo-of-a-saigon-execution-50-years-ago-shocked-the-world-and-helped-end-the-war/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.5374c97d4477

- Prescott, T. L. Appropriation and Representation. Image Journal, (97). Retrieved from https://imagejournal.org/article/appropriation-and-representation/

- Mitchell, R. (2018, March 31). A ‘Pearl Harbor in politics’: LBJ’s stunning decision not to seek reelection. Retrieved April 26, 2019, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/03/31/a-pearl-harbor-in-politics-lbjs-stunning-decision-not-to-seek-reelection/?utm_term=.cdd2e6ec89aa

Incels ‘cash out’: gendered violence and the economies of hate

Posted on by smisu13p

A post written by Jazzlin Carr, based on an ANTH424 assignment.

“He doesn’t seem like that bad of a guy. He just seems hurt, like he just wants a friend or support. I always thought incels were really bad people, but he seems like a good version of them.”

I looked over at my very liberal, ultra-feminist, Jacinda Ardern-loving partner in disbelief. We had just finished watching a YouTube video from the channel Jubilee entitled “I’m An Incel. Ask Me Anything.”.[1] The short clip features a self-proclaimed incel responding to questions from the public. While his identity is hidden from those asking the questions, he is shown to the camera.

A screenshot of the Youtube video “I’m an Incel, Ask Me Anything” posted by Jubilee. In this particular frame, a woman appears to be pointedly interrogating an incel named Derrick, whose demeanour and open palms facing up depict a certain passivity and openness. Source: https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=incel

An incel, otherwise known as an “involuntary celibate”, is a self-imposed label used by mostly young males who define themselves by their inability to secure romantic or sexual partners despite having the desire for them, often attributing this to their anxious or shy behaviours, women’s high standards, or their unattractiveness or below-average characteristics. [2] They are most often found in online forums, where discussions are often characterized by self-loathing, resentment of more attractive males (known as “Chads”), and misogyny.

This definition, however, is fluid depending on who you ask. As one incel claims in his blog, anyone can be an incel “as long as they show signs of […] struggling with attaining romantic relationships”. [3] Others, myself included, would characterize the self-radicalizing nature of incel communities as a key part of the definition. Take a scroll through one of the few incel chatrooms that have not been blacklisted from internet servers and you’ll be hard-pressed to find a single discussion that does not dehumanize women, promote racist ideologies, encourage violence, or celebrate incels who have murdered women out of spite. [4]

You may not have assumed such a thing if your only portrayal of incels is from the Jubilee video I noted above. The incel featured, named Derrick, coolly responds to a variety of questions. He reacts to leading questions with calmness and ensures the interviewers that he is there “to give more of a positive light on [the incel] community”. He discusses his mindset, believing that “promiscuity leads to increased standards in more primitive aspects such as looks and that typically makes it harder for some people to find relationships” and generalizes this to cities such as “[Los Angeles] or London, or in Auckland, New Zealand”. He notes that it was “constant years of rejection” that led him to more “radical beliefs” which he equates to “old beliefs”. It is also noteworthy that he was very quick to say that he condemns the actions of mass murders identifying as incels. Instead, he thinks “the reason why they committed those actions was […] desperation, or […] mental problems.”. When watching the video again, I can understand where my partner’s empathy to Derrick comes from. His demure presence, calm responses, and position as a “traditionalist” who has been hurt time after time again presents a convincing case towards justifying the incel perspective as a matter of difference of opinions, or a wounded community seeking internal support.

But what is the actual impact of this point of view, on the lives and bodies of women? I turn to the writing of British-Australian scholar, Sara Ahmed, to explore this:

In her book The Cultural Politics of Emotion, author Sara Ahmed discusses the organization of hate, and considers its circulation as both a defence mechanism for those who see another body as a threat to something they love, as well as its impacts on the figures who have been aligned by the narrative of hate as the “common enemy”. [5]

Her analysis seemed fitting for this topic and applying it to the performance of incels has me wonder if it may clarify why Derrick’s narrative could almost seem, dare I say, justified.

In a chapter on hate, Ahmed’s overarching theme is that hate operates as a sort of economy. Essentially, hate is fluid and moves between bodies and signs, and is not fixed on one subject. If an incel posts a rant on a chatroom about his displeasure with a woman who rejected him that day, the specific woman involved is simply a “nodal point in the economy”. The hate has another origin and destination, one which is more broadly connected to the perceived threat towards something the incel desires. In this instance, it may be their desire for a relationship and feeling loved. From this perspective, the hate’s origin was not in the encounter with the individual woman, but rather in years of rejection. The destination of that hate is not towards her, but rather, to a common body of women which the incel deems as a threat to ‘traditional’ relationships that they wish to participate in, but feel they are blocked from. In this example, we see how an incels hate is economic.

It is this inability of hate to be fixated that allows it to grow and fester in these groups. The vagueness of the enemy allows for particular narratives to be applied to any individual who may appear to be a part of that group. In the case of the incels, any woman could therefore fit the narrative as being a threat to traditional relationships.

But how does this economy of hate affect the bodies of the group considered a “threat”?

Derricks relatively innocuous comments contribute to the investment of hate towards women by furthering a narrative that their desire for more liberal roles and modern lifestyles is raising their expectations of men to the extreme, so that more traditional or less attractive men can no longer find relationships or love. For one, it is rhetoric that seals female bodies as objects of hate. This kickstarts a chain of effects that promote and support violence. It contributes to real physiological symptoms for those who must live in these bodies in a number of broader ways too. This is evident in the below photo, selected by Stuff for its news article on the event in 2015, which depicts the consequences of incel behavior on women who are not direct victims of its violence, who instead may suffer from fear, post-traumatic stress disorder, nightmares and anxiety

Two women comfort each other following the Umpqua Community College in Roseburg, Oregon. This attack killed 10 and injured eight others. The attacker was an incel, who expressed sexual frustration and blamed women’s standards for his virginity at age 26. Credit: Steve Dipaola/Reuters. Source: https://www.stuff.co.nz/world/americas/72625797/10-dead-in-shooting-at-umpqua-community-college-in-roseburg-oregon

If hate is an economy, it also performs as a form of capital. The effect of an incel’s hate does not reside solely in the individual object of their displeasure, but rather accumulates over time. I would take Ahmed’s imagery of hate as an economy a step further, and argue that is when these investments pile up and a member of the threatened community tries to “cash out” on this accumulated capital of hate that violence is used as a defence against the hated bodies. The collection of testimonies of rejection, frustration, and disappointment found on these incel chat rooms becomes so overwhelming that an incel feels justified in reacting with violence, in the same way as a person who has accumulated savings may feel enticed to splurge with the surplus.

The investment of hate on these chatrooms is made evident in the justification of violence on women when researching any of the major incel-led terror attacks of the past couple decades. After a one self-described incel posted a 137-page manifesto to a chatroom in 2014, he would thereafter kill six people and wound fourteen more in Isla Vista, California. The reaction from the online incel community was one of praise; his face quickly photoshopped onto Christian icons, and his name being associated as the “primary incel ‘saint’”, a reflection of how they believed he was the saviour of incel values. [6] In 2015, an incel in Oregon shot and killed nine classmates and a professor, and injured eight others, in what he described in his manifesto as the reaction of his frustrations to being a virgin at 26. The reaction from the incel community was one of support and empathy, with one user commenting a poem, reading “society failed him/it’s not his fault/don’t blame him/he was the hero we deserved.”. [7]

A screenshot taken from an incel forum in August 2020. The commentator notes how the van attack in Toronto was “lifefuel” for them. They go on to note preferred methods of killing in “ER” attacks, a popular incel abbreviation for violent attacks. “ER” is a reference to the initials of the “Saint” of the incel community, the Isla Vista killer. Source: http://wehuntedthemammoth.com/2018/04/24/incels-hail-toronto-van-driver-who-killed-10-as-a-new-elliot-rodger-talk-of-future-acid-attacks-and-mass-rapes/

In 2018, an incel in Toronto, Ontario used a rented van to kill ten victims and injure an additional sixteen, as a form of revenge for perceived sexual rejection from women. Most clearly evidencing the use of hate as capital for the incel community, one commentator on a chatroom posted “This shit right here is lifefuel for me”. [1]

A photo (taken 24 April 2018) of the impromptu memorial created by local residents after the Toronto Van Attack, where a man drove along the sidewalk for 2 kilometers, purposefully hitting as many pedestrians as it could. The perpetrator posted on his Facebook account shortly before the attack, with a statement referencing a man considered to be the “Saint” of incels. Credit: Quentin9906. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The original quote from my partner, that opened this blog, shows how important it is to grasp the economy of hate. Even though my partner did not agree with Derrick’s views, the empathy he felt for him could be a slippery slope into justifying the mindset of an incel, thus giving their alignment of female bodies as a threat imagined ground.

The accumulation and investment of this hate is what contributes to not only the everyday pain and victimization of women but leads to the in-group justification of violent expressions of hate, performed in terror attacks such as those mentioned above. In recognizing the performance of hate as an economy, one can work to actively question its impacts and limit the influence one perspective may have on the incel community.

References

[1] I’m An Incel. Ask Me Anything. (2019). YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DdHqzr4DyIs.

[2] Opinion | Men are in trouble. ‘Incels’ are proof. [online] Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/men-are-in-trouble-incels-are-proof/2019/06/07/8d6ad596-8936-11e9-a870-b9c411dc4312_story.html.

[3] SeventhQueen (2020). The Incel Among Us. [online] Incel Blog. Available at: https://incel.blog/the-incel-among-us/

[4] Inceldom Discussion [Online] Incels.co Source: https://incels.co/forums/inceldom-discussion.2/

[5] Ahmed, S. (2015). The cultural politics of emotion. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

[6] Beauchamp, Z. (2019). Incels: a definition and investigation into a dark internet corner. [online] Vox. Available at: https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/2019/4/16/18287446/incel-definition-reddit.

[7] bust.com. (n.d.). ‘Beta Males’ Want To Kill Women Because They Can’t Get Laid. [online] Available at: https://bust.com/feminism/15551-mo-beta-blues.html

[8] We Hunted The Mammoth. (2018). Incels hail Toronto van driver who killed 10 as a new Elliot Rodger, talk of future acid attacks and mass rapes [UPDATED]. [online] Available at: http://wehuntedthemammoth.com/2018/04/24/incels-hail-toronto-van-driver-who-killed-10-as-a-new-elliot-rodger-talk-of-future-acid-attacks-and-mass-rapes/

Posted in ANTH424 (Anthropology of Evil), Case study, Media/political commentary | Tagged anthropology, cultural anthropology, gender, gendered violence, hate, Incel, Misogyny, Sara Ahmed, Social anthropology, terrorism, violence, women | Leave a reply