Hip-hop Dunedin: An ethnographic soundscape

A soundscape produced by Biruk Mengstu, for ANTH210 (Translating Culture)

About the soundscape:

My research question was around the influence of Hip-hop on some students in Dunedin. All these sounds were retrieved from the fieldwork (studio apartment and live underground hip hop showcase) and reconstructed to tell a story of the extent of influence hip-hop has on these students.

My research question was around the influence of Hip-hop on some students in Dunedin. All these sounds were retrieved from the fieldwork (studio apartment and live underground hip hop showcase) and reconstructed to tell a story of the extent of influence hip-hop has on these students.

About the ANTH210 process:

Throughout my high school and university life, I have always been interested in the natural science field. However, I have always wanted to learn more about my surroundings and the social science aspect. When I found out about the ANTH210 paper, I thought it would be an excellent opportunity to challenge myself and to get out of my comfort zone as I have never taken an anthropology paper before.

This paper has opened my mind to a different way of thinking and has shown me that there are so many different cultures that are all around which we sometimes don’t realise. This paper has allowed me to get in touch with my creative side, which I never really had the chance to express before. Overall I enjoyed and learned a lot by being a part of the Anthropology 210 (Translating Culture) class.

Easy Words: An Open Letter to Critic

Dear Critic – Te Arohi – Student Magazine,

Title image from the Critic article [25th Feb 2019]

To be honest, I think we were more perturbed about the handful of our papers that you decided were too ‘difficult’ to include.

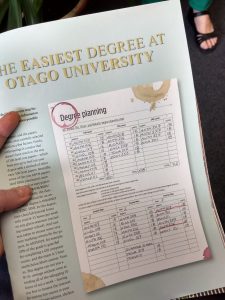

Critic’s dabbles in degree planning… featuring ANTH325 (Death, Grief, and Ritual) and ANTH327 (Anthropology of Money)

But it makes me think a little more about why we study what we do, at Uni. Why would we want a degree that was ‘easy’? Critic’s analysis of a dream degree holds some internal contradictions about achievement, it seems to me…

The article is a ‘how to’ guide for the minimum effort possible to achieve a qualification. This is erroneously calculated of course: all 18 points at the University of Otago are designed to be around 10 – 15 hours of both contact and non-contact time per week. Papers pass through a rigorous review to ensure this – ask the OUSA education officer, who sits on these Divisional Academic Committee Meetings!

Social anthropology papers include large amounts of background reading, ethically approved fieldwork and independent study and analysis, alongside contact hours – skipping over these elements of learning are not the pathway to an A+ but perhaps a C.

But let me return to what it is that we value in our degrees. Is it the piece of paper and a string of Cs? Or is it the experience, the self awareness and critical insights that a capacity for life long learning instills in us? Critic has one answer, but a lot of my own students have another:

“Your course [in social anthropology] has profoundly influenced my path over the last 7 years: I’m currently a student midwife at Ryerson University, Canada, and think back often to the critical and curious lens that your teaching afforded me… In my work, political life, and student life, I work to ground myself in the engaged critical practices I was lucky enough to learn from professors like yourself…I really credit your course as an important part of why I do the work that I do!

– Unsolicited email, Alumna, 2009

In fact, dear Critic, it is thanks in fact to these very (critical thinking) skills, that our students have been so quick to place your article into its wider socio-political context – an ideological shift towards devaluing the humanities.

In Facebook comments and hallway conversations, many made a clear and disgruntled connection between this article and a bigger trend of “arts bashing”, and jumped to defend their degrees accordingly. One recent BA (social anth) graduate shared:

“I studied damn hard to get my Anth major […] they’re so much harder cause it’s not just straight up facts but looking into things and understanding lots of different ways to see something.”

Another BA(Hons) social anth graduate says:

“clearly no one at critic has actually taken any Anth papers! Easy is not the word I’d use… Diverse and broad based perhaps… I mean where else do you get to cover papers in one subject on medicine, death, reproduction, economics, religion, evil and supernatural forces, globalism and philosophical movements.”

Yet another affirms that the experience hinges on if you “take the time to really make an effort”. Perhaps ‘easy’ is an approach, rather than a characteristic of any one paper or degree.

Graduation 2018: Prof Ruth Fitzgerald standing with BA (Hons) Social Anthropology graduate Jennifer Bell. Jennifer was offered a job at the Ministry of Justice, before she had even finished the year.

So let me encourage and admire all of our past and present students who have worked hard to engage meaningfully with their studies, and who have achieved distinctions like local and international scholarships, and awards for their dissertations and conference presentations. Not to mention all of those marvellous transcripts full of B’s and A’s, achieved through hard work, integrity of purpose, and dedication to the ideals of good scholarship.

I think it’s easy to see the difference.

Yours Sincerely

Prof. Ruth Fitzgerald

Social Anthropology Programme, School of Social Sciences

“I did this, and this is anthropology!”: Interning at a Community Non-Profit

Though many of us who study social anthropology have a keen interest in helping others, from an uncomfortable seat in a crowded lecture hall it can often be difficult to envision how skills being learnt in the classroom might be applicable in a broader setting.

Here postgrad Social Anthropology student Jordan Webb interviews undergrad student Mika Young[1], about their experience participating in the new HUMS301 humanities internship practicum where they had a chance to translate anthropological theory into ‘real’ world practice at a community organisation; Life Matters Suicide Prevention Trust.

Q. Could you briefly explain the humanities internship paper?

A. I guess it’s about applying what you have learnt in class to a practical context. Every student will go out to an organisation in the community and do some sort of project for them, whether it is research or a practical project. Mine happens to be a mix between the two. Since I already have experience working with organisations in the community, I am helping Life Matters Suicide Prevention in creating a new volunteer training programme.

A. I guess it’s about applying what you have learnt in class to a practical context. Every student will go out to an organisation in the community and do some sort of project for them, whether it is research or a practical project. Mine happens to be a mix between the two. Since I already have experience working with organisations in the community, I am helping Life Matters Suicide Prevention in creating a new volunteer training programme.

Q. What initially drew you to this internship opportunity?

A. I often find it difficult to communicate with people about what anthropology can offer outside of research. So I thought because I am already interested in pursuing community work after my degree that this paper would be a good chance to learn how anthropology works in a practical sense. To get some experience in the area, and then be able to communicate to other organisations, this is what I have done and this is how I can help you.

Q. How did you use your anthropology major during your placement?

A. I drew a lot from Wollcot’s ‘3 E’s’ – experiencing, enquiring, and examining[2]. I think it is really useful drawing on your own experience, doing the research to make sure you are well informed, and also talking to people and including their experiences. So for the organisations I researched on behalf of Life Matters, it was important to hear their perspectives on their existing training programmes. That’s how I try to see anthropology, and when I am going into an organisation I make sure I’ve covered these three aspects

Q. There has been a lot of talk in the tertiary teaching community about capstone papers which consolidate entire undergraduate experiences, how does this relate to your experience?

A. I’d say very well in the final semester of my degree. That was another motivating factor as I think it helps to bridge between academic and public world beyond, particularly with anthropology as it can be difficult to communicate what your skills are. It gives you an example of, ‘I did this, and this is anthropology’!

Q. How has this experience helped you to communicate the potential applications of anthropology?

A. It’s still a challenge! I think this also a difficulty discipline wide, translating anthropology for a the general public. But it is definitely nice having this concrete example of how a practical task could be approached from an anthropological perspective. For example, one thing that I was able to offer was approaching other organisations and translating the knowledge they had already developed, in combination with my own volunteer experience, and contributing an anthropological understanding of why this information is important. It helps the organisation as much as it helps me, providing them with a new perspective.

Q. What was your overall impression of the internship and paper?

A. I thought the biggest challenge would be making the paper count toward my anthropology major, but that aspect seems to have been quite seamless. In terms of, workload, the initial groundwork and planning took a lot of time and effort, but after that three week period it became a lot easier to manage my own workload as I became more familiar with the role and the organisation.

Q. Would you recommend the paper to other students?

A. Definitely! I think it is good practice to make those conceptual links between what anthropology is in the classroom and how you can apply that to different situations. I think a lot of students struggle because anthropology is so broad, everything can be anthropology if you want it to be! So the paper helps with developing both anthropological skills and real world skills, and being able to keep an open dialogue with organisations about how anthropology can be used to help them.

A. Anyone can do the internship, but being open to adapting, developing communication, and being willing to learn will all add to the value of the paper and the role. The advice I would give to others would be to find an organisation that suits your interests and experience, and find out what works best for you.

***

Many of us are interested in translating anthropology: imagining how we might be able to benefit our communities once we finally graduate! As Mika has suggested, the humanities internship paper might be one of the ways to help negotiate this transition, and to develop and refine ethnographic skills through sharing their application with others.

As Mika remarked, “The tools we are learning are helpful in an academic context but they are also just life skills! It is challenging finding applied uses for anthropology, but ultimately it is about being human, right?”

[1] Mika Young was also the winner of the 2018 Sites Senior Student Essay Competition.Their winning essay is entitled ‘Tā Moko and the Cultural Politics of Appropriation’, and will be published in the 2018 December issue of Sites.

[2] Wolcott, H.F. (2008). Ethnography: A Way of Seeing. 2nd ed. Blueridge Summit: Altamira Press.

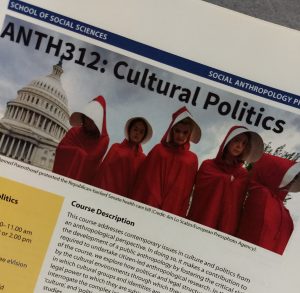

A crash course on the anthropology of evil

Posted on by smisu13p

Dr Susan Wardell teaches a course called ‘The Anthropology of Evil’ (ANTH424). Last week she responded to the Christchurch mosque shootings with a twitter thread, drawing on course content to ask pointed questions about social patterns of sense-making in New Zealand, and in the media, in the wake of the attack. The full (19-point) thread is available in the link below, and also pasted as text below

https://twitter.com/Unlazy_Susan/status/1107760378694385664

Crash course: I teach a paper called ‘The Anthropology of Evil’ at

@Otago. It just got very real. This thread will unpack some ideas from the course in relation to the#ChristchurchTERRORISTattack. Questions, not answers.#anthropology#anthrotwitter#ChristchurchMosqueAttack [1]When the world is shattered, human meaning-making kicks in fast. We try to ‘locate’ evil within existing worldviews, including theological, secular, and academic. We collectively ask what/who/where, & WHY?! This gives us the social resources to assign blame, prescribe action. [2]

What is ‘evil’? An inherent quality of a person? Their intention/motivation? The action itself? The consequences of the action? Watch how the media and legal system frames this for

#ChristchurchTerrorAttack. And what about a white supremacist who has never committed violence? [3]What role can social scientists play in responding to the

#christchurchtmosque attack? Should we be thoroughly analysing moral topics, whilst bracketing our own views (Fassin 2009), or formally taking sides, being politically engaged (Scheper-Hughes 1995)#anthrotwitter [4]Does social science have a language appropriate to representing suffering? Is this thread itself unethical, in its stilted, theoretical removal from very real pain, grief, loss of the

#ChristchurchMosqueShootings? How should we analyse atrocity without being reductive, cold? [5]I’ve seen many posts arguing against learning the terrorists name and background because they don’t want to ‘humanize him’. It’s easy to create a ‘monstrous’ other. Monster = not human. But he is a human. That’s scarier to acknowledge. HE is us, as well as ‘they’ are [6]

The terrorist is described as ‘evil’.”‘Evil’ is part of the vocabulary of hatred, dismissal, or incomprehension” (Morton 2004). SHOULD we seek to understand the lives, worlds, & thinking of white supremacists? Are condemnation & understanding incompatible? [7]

#anthropologyHow are we fitting the story of the

#christchurchmosqueattack into existing, familiar narratives? What is the risk? Yesterday a student & I bet that we would soon see references to mental illness – a common narrative for white male violent offenders. Came true within hours. [8]What elements of news about the

#christchurchmosqueattack have affected you most? I’m going to guess it’s the images. Images are sometimes seen as a more authentic language for pain than words, but also function to ‘frame’ complex realities. Reflect on the ones you’ve shared [9]Kleinman (1996) warns that mass media circulation of images means suffering can be “remade, thinned out, distorted”. Susan Sontag saw photography as ‘predatory’. Let’s think about: who took the images and why? Who is sharing them, and why? Who is in them, and who isn’t? [10]

Frosh (2016) discusses digital morality: the cursor as a proxy moral compass. What do we click on, or watch, & why? A sense of obligation to ‘witness’ tragedy? Empathetic hedonism? (Recuber 2016, also see: https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/inplural/wp-admin/post.php?post=122&action=edit … ) What would it mean to NOT watch/view/click? [11]

Lots of discussion about what NOT to view (the manifesto, the livestream). Calls to give attention to victims, not perpetrator. We are exercising agency, within the ‘attention economy’ of social and mass

#media. Capital-driven systems, but with room for resistance. [12]What makes something or someone LOOK evil? How are particular features of particular bodies, coded as evil? Places and objects can also take on strong (through fluid) meanings, and emotions. What have mosques symbolised in NZ in the past? Now? What about the hijab? Guns? [13]

A typical terrorist tale involves a villain who has infiltrated a community, but is an outsider (Loseke 2016). Does the fact that the

#christchurchmosqueattack terrorist was an Australian, change how NZ will address its own racism? Do we still get to be the ‘goodies’? [14]How does hate come to circulate around specific people, bodies, or identity markers? Sara Ahmed (2004) writes is not not just part of ‘extremism’ and crime, but is a “product of the ordinary” Hate crimes do not just involve visceral power, but broader structures of power [15]

‘Banal’ evil refers to everyday, complicit, thoughtless evil (not sadistic malice). Is racism in NZ like this? Is racism part of ‘structural evil’: the longstanding formal (legal/bureaucratic/political) systems that discriminate and harm through their normal functionality. [16]

It’s through the cultivation of collective emotions that people come to FEEL, to BELIEVE in the imaginary social unit called the ‘nation’. In NZ’s past, who has been ‘othered’ to build a stronger sense of ‘us’? What does it mean to now say ‘they are us’, & is it enough? [17]

There has been talk about lack of Muslim voices even in the mainstream media coverage of the

#ChristchurchTerrorAttack. Testimony has a power not despite, but BECAUSE of subjective experience. When Muslims say they are shocked, broken, but not SURPRISED, are we listening? [18]Silence can help diagnose power. We must pay attention to silences, gaps in narratives, forgetting, vagueness, or selective remembering, about our own history, including the many instances where white supremacists acted publicly in NZ before this, as pointed out in a blog post by Catherine Trundle (an anthropologist from Victoria University, Wellington): https://bit.ly/2TIJ4Ti [19]

Posted in Curriculum and Pedagogy, Media/political commentary | Tagged anthropology, christchurch mosque shooting, Christchurch terrorist attack, evil, islam, media, othering, pedagogy, Social anthropology, teaching, terrorism | Leave a reply