Contrasting Evils: The raising of the Soviet flag over the Reichstag building

Written by Etienne DeVilliers, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

World War two was one of if not the most costly wars in human history. It has had ongoing significance in global spaces and memory like almost no other event in human history.

The final days of this far-reaching conflict were of particular importance to two groups; the USA and the Soviet Union. In many ways both were trying to present themselves as the hegemonic power of the future [1] with the USA pushing capitalism and the Soviet Union Communism. In particular the “race for Berlin” encapsulates this – with the USA, the French and the British approaching from the western front, and the Soviet Union approaching from the Eastern Front. In many ways, in the closing days of the war the USA were facing two enemies, the remnants of the Axis (in the Japanese and Germans) but also their supposed ally, the Soviet Union [2].

The raising of the Soviet flag over the Reichstag Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raising_a_Flag_over_the_Reichstag#/media/File:Reichstag_flag_original.jpg

An image that encapsulates this complex and nuanced state was the photo of the Raising of the flag of the Soviet Union over the Reichstag building in Berlin in 1945.

Changing meanings, shifting allegiances

The image of the flag on the Reichstag represented different thing to the two hegemonic powers of the USA and the Soviet Union. To the Americans in was a symbol of the raising of a great evil, to the Soviet Union it was a symbol of victory and revenge over an unjust enemy.

The photo itself shows 3 men raising the red flag with the hammer and sickle over the Reichstag surrounded by plumes of smoke. The photographer, Yevgeny Khaldei, stated that he was heavily inspired by the American WWII photograph of the raising of the flag on Iwo Jima, and wished to do something similar. Soviet Union sensitivities meant that Yevgeny Khaldei was not known to be the photographer for many years, the identity of the three men was also unknown until relatively recently.

The imagery present in the photo has shifted meaning drastically over time, as well as having very different meanings within different countries and political alignments.

For the Allies, the Reichstag was in many ways a symbol of their enemy – being in the past the center of German government, the building itself was symbolically constructed to symbolize a unified Germany following its unification in 1871. The Reichstag was covered with statues and images linked to Germany’s mythic past. This highlights the symbolic importance of the Reichstag despite it not being built by the Nazis it reflected much of their ideology. Due to its importance in German history, identity and politics it became a symbol to the allies to – an embodiment of Nazi Germany, and a symbol of what they fought against. This was why the Reichstag was at the center of the Soviet attack on Berlin, despite the fact that it had been a shell of its former self for about 12 years after it was burnt down in 1933.

It was in late April/early May of 1945 that the Reichstag was captured by the ‘red army’ [3]. Many soviet flags were raised on the Reichstag. Out of all the flags raised only one remains in existence today; often referred to as the Victory banner, alluding to the connections of the capturing of the Reichstag and victory within the Soviet mind-set [4]. The victory banner is used at ceremonies commemorating the end of World War 2 and has become of symbol of victory over evil.

Freedom, fascism, and the communist as liberator

Another way that the specific imagery within the photo has be construed by contemporary groups is as a symbol of “Victory over Fascism” by groups such as the international Freedom Battalion (IFB) a far left militant group fighting in places such as Syria against groups such as ISIS [5]. Below is a photograph taken by the IFB in the Syrian city of Raqqa clearly echoing the photo of the Soviet flag on the Reichstag:

The raising of a soviet flag in the Syrian city of Raqqa Source: https://external-preview.redd.it/vFh4-62I3K04F-sgB3qwrxFytHBqY3hK-9BpFYFZbXU.jpg?auto=webp&s=3b37f8dab75a94068502729d08f518d10ae26cbd

To the IFB the photograph represent victory over the evil of facism and as the flag over the Reichstag represented victory over the Nazis the flag in Raqqa to them represents a victory over the Fascism of ISIS [5]. In that regard the Flag raising of the Soviet flag fits into larger trends namely the appeal of experience [7].

This photographic reproduced advances the perception of a continuing tradition of Communists working as liberators. When questioned in regards to the photo these sentiments among IFB members become even clearer “When the red flag flew over Berlin, it was the symbol of victory over nazi-fascism. We consider Raqqa to mean the defeat of Isis-fascism and ourselves to be in the same communist tradition as the liberating troops.”[5]

However, from the perspective of the USA (and many others in the Western block) the image of the communist hammer and sickle on the Reichstag must have seemed an image of two evils: the dying evil of Nazi Germany and the raising evil of the Soviet Union.

We can see this image, showing Soviet Victory over, and the evil it evoked to the Americans, as contributing to the American decision to use the only two nuclear bombs ever used in warfare [2], in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as a display of strength in the face of their greatest rival, the Soviet Union. Yet this act can be interpreted as evil as well.

Contemporary Controversies

As the power of the Nazis waned and the cold war started with the raising of the iron curtain and the division of Berlin the image of the Soviet flag over the Reichstag would have taken on a whole new meaning, a symbol of a race lost…. as well as a symbol of the division of Berlin, and by extension Europe and the world, into the Eastern block and the Western block, separated by an ‘iron curtain’. Thus it was in the wake of the Cold War that the Soviet flag became to many a symbol of evil in a new way.

This can be seen within contemporary spaces where the Soviet flag no longer commands the political power it once did, it still conveys it. To some it represents liberation and equality but to others it still represents the great other of the Cold War as well as a great evil.

An example of the complex space in which the Soviet flag now sits, its raising at the funeral of a man who had been a communist in Stalybridge, in England in 2019 [6]. From the perspectives of the family it was honoring a relative but to the wider population of the town and wider society it was a brought forth feelings of dismay and outrage [7].

The controversial raising of a Soviet flag at a funeral in Salybridge England. Source: https://twitter.com/guidofawkes/status/972131282644856834

The outcry on social media echoed these sentiments within the population as many considered it inappropriate, following a recent suspected Russian involvement in a nerve gas attack on a journalist. This is due to the intrinsic link the Soviet flag has to Russia, and by extension its connection to the suffering inflicted on people by the Russian state.

The ideas surrounding the two evils present in the photograph of the raising of the flag over the Reichstag have not remained static through history. Rather they have be reshaped by time and by space.

In contemporary Russia the photo is a symbol of righteous revenge, and victory over Nazi Germany. For the USA its meaning has shifted, with the raising of the Iron Curtain and the pressures of the Cold War to come, as a former ally became their greatest enemy. A two very different ideologies clashed, for the USA the Flag of the Soviet Union became an evil as great as the evil incapsulated by the Reichstag itself.

References

- Wallerstein, I., 1993. The world-system after the cold war. Journal of Peace Research, 30(1), pp.1-6.

- Sherwin, M.J., 1995. Hiroshima as politics and history. The Journal of American History, 82(3), pp.1085-1093.

- Hicks, J., 2017. A Holy Relic of War: The Soviet Victory Banner as Artefact. Remembering the Second World War, pp.197-216.

- Tony, L.T.M., 2013. Race for the Reichstag: The 1945 Battle for Berlin. Routledge.

- Oak, G. 2018. A red flag over Raqqa. The Morning star retrieved from: https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/red-flag-over-raqqa

- Bugby, T. 2019. Family explains flying of Soviet flag in Stalybridge retrieved from: http://www.stalybridgecorrespondent.co.uk/2018/03/10/family-explains-flying-of-soviet-flag-in-stalybridge/

- Kleinman, A. and Kleinman, J., 1996. The appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times. Daedalus, 125(1), pp.1-23.

Selling Che: the commodification of a communist icon

Written by Jayden Glen, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

Images are powerful. They can inspire fear, love and even sadness. As the common saying goes, ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’. But images can be manipulated out of their original context, and be used to enforce values against their original intention, as shown by the commercial circulation of images of Che Guevara.

Giving Context to the Iconic Image

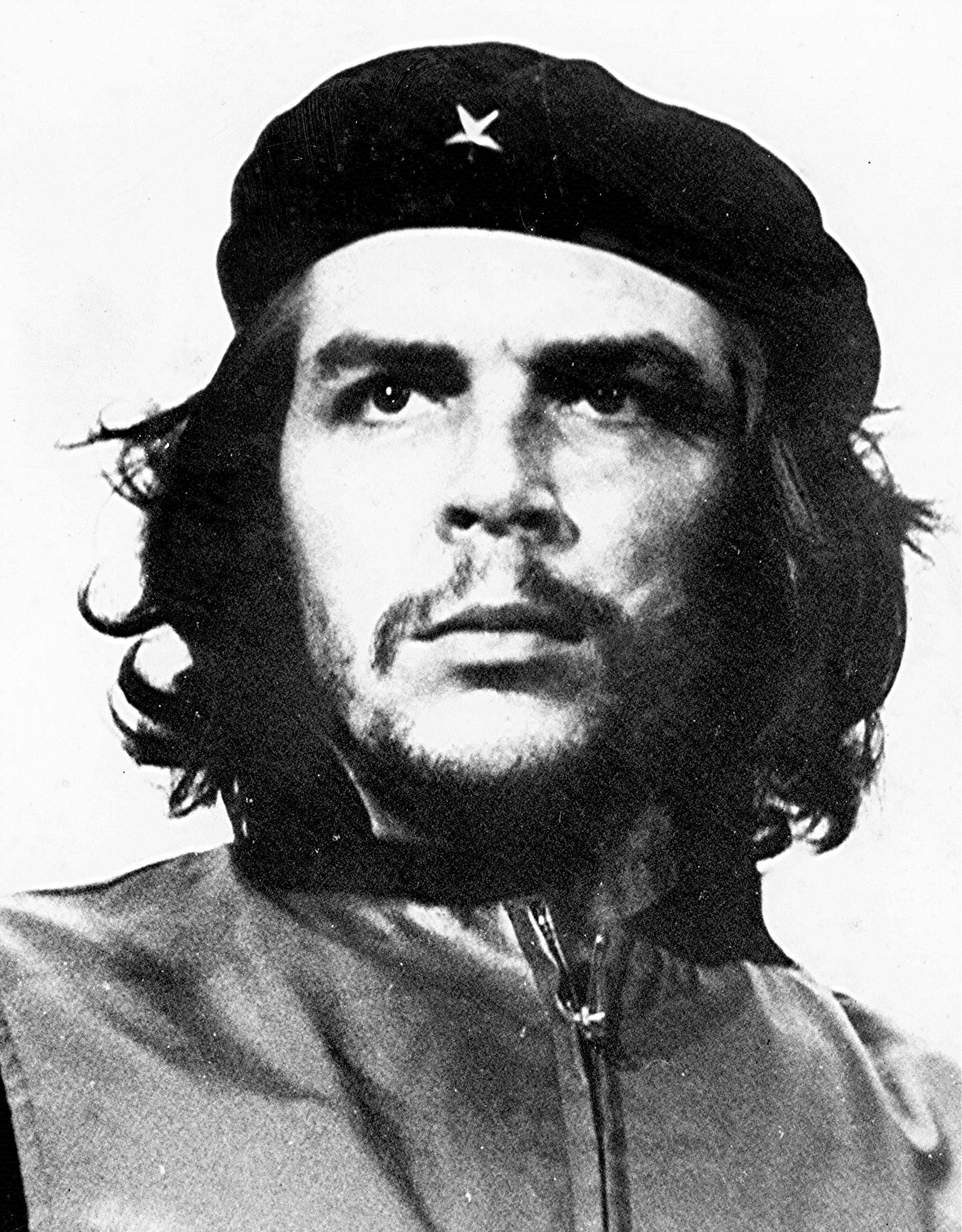

The Guerrillero Heroico or the “Heroic Guerrilla Fighter”, is an iconic photo of Che Guevara, an Argentine Marxist revolutionary from mid 1900’s Cuba.

Guevara fought for communism in Cuba, becoming a strong symbol of the revolution. He remains controversial because of the many extreme measures he took in this fight, despite being widely revered. This iconic picture of him was taken by Alberto Korda on March 5th 1960, during a funeral service for lives lost as a result of the explosion of a munitions freight boat.[1]

The photographer was, at the time, working for the Cuban newspaper Revolución. Koda explained that he was struck by Che Guevara’s powerful expression, a stare over the crowd that showed “absolute implacability”, anger and pain.[1] The newspaper never printed this photo in its coverage of the service, but Koda held on to the portrait in his own studio.[1]

It become “viral” in 1967 when Koda gave two prints to an Italian, who published it for the Cuban government. The photo then began to show up all over the world – particularly in magazines and newspaper, and then in popular culture, such as the colour poster done by Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick.[1]

Che’s later execution in October 1967 cemented his place in history, and this photo in particular would immortalize Che in popular culture too.[1] But I argue that the commercialisation of his image is itself evil, as it goes against the morals that he embodied.

The evil nature of commodifying Che

In popular culture Che Guevara’s face has become a symbol for “the power of individual expression”, reinforcing ideas of resistance to conformity and oppression.[2] These ideas resonated with many people and groups at the time, and continue to do so today. In fact, stylised as it often is into a stencil/pop-art look, as a cultural artefact the “Heroic Guerrilla Fighter” has become one of the most popular and marketable images of all time.

Screenshot of some of the merchandise available from www.thechestore.com, where as we can see Che Guevara’s image and other images of communism being used for profit.

Many (though not all) people may purchase these items because they share a degree of resonance with Che’s political philosophies. But the irony is that “Che would have used the royalties from any such commercial ventures to destroy the social and economic system that produced them”.[2]

The mass consumption of Che’s imagery, I believe, is reflective of what is termed “disordered capitalism”, a term used to describe how aspects of morality and politics are now intertwined with the commercial.[3] This is most observable is in the commodification of suffering, where “experiences of atrocity and abuse” have become highly profitable. This applies to the marketization of Guevara’s image primarily because his global profile occurred after his death – via execution. The significance and viral popularity, implicitly references this.

Che devoted his life to fighting against a capitalist system that in his view was significantly destroying the way of life of poorer people. As well as making money off his martyrdom to this cause, commodification of his image ignores the pain and suffering he endured through his revolutionary campaign while alive, and ignores the suffering of the people he fought for.

From an anthropological lens, this is also a case of global and local systems interacting. The image is consumed by global ‘fans’ and profited on by companies in many other countries. But the sale of his image undermines the political and ideological value that he has as a symbol to Cuban citizens in particular. The commodification of his image shows an attempt to disempower his communistic ideals.

In their analysis of suffering and its representation in media, Kleinman and Kleinman discuss suffering as “one of the existential grounds of human experience”.[3] But in a saturated media age, they argue that North American society has become de-sensitized to images of trauma.[3] Moreover many engagements with the suffering of others, via the media, are as part of a commodified system where cultural capital is gained through the presentation and circulation of trauma stories. So much so that complicated stories are reduced “to a core cultural image of victimization”.[3] Stories like Che Guevara’s become lost in an over saturation of his image, and other images of suffering – removed from context and significance, now bearing cultural and economic capital but losing moral and political potency.

A moral use of images

Frosh’s (2018) work on the way a sense of moral obligations can shape public interactions with stories and images of suffering, can help further unpack the complexities of commodifying and consuming Che Guevara’s image. In his study of Holocaust survivor testimonies, Frosh [4] reinforces that through the production and consumption of these testimonies through digital sites, individuals express and experience a “moral obligation to the past and to the dead”.

Can the same be said of Che Guevara? Should there not be a moral obligation to preserve the mindset and values of this deceased man? If so, should it be via consuming his image as a product, or by refusing to?

There are other reasons of course why this image may be rejected. Che is controversial because while he was viewed by a freedom fighter and hero by Cubans oppressed by the capitalist system of the time, he was also seen as a violent extremist and dictator: in the pursuit of revolution and freedom.

While there are many valid arguments against the man himself as, it is important to stress that even men perceived as evil can generate genuine love and admiration from people. Che is treated with and regarded as a Saint in some parts of the world due to his fight against oppressive and demeaning forces of capitalism – for example in Bolivia, where many worship him as “Saint Ernesto”, or in Cuba, where residents of Havana worship and pray to “Saint Che” by lighting a candle.[5]

As well as obligations to the dead, Frosh talks about obligations to the witness-survivor. In relation to Che Guevara, this could be examined in relation focused toward those that continue to praise and revere Che as a central part of their political ideology, and their real and personal history – in Cuba in particular, but also further afield.[4] This includes those who fought with him and for his cause, and continue to today. It includes intellectuals, workers and students.

We can apply Frosh’s idea to highlight a moral obligation to those living people connected to Che Guevara – those that remember and revere him. Including those Cubans that Che attempted to save as they were belittled and demeaned by an oppressive capitalist system. How would this additional layer of obligation be enacted, in our engagement with this image?

Concluding (and condemning)

Image retrieved from: https: //www.allposters.com/-sp/Che-Guevara-Posters_i1181_.htm accessed 8/4/19

Che Guevara was (and is) a controversial and influential figure. In examining the use of his image I have demonstrated the complexity of moral engagements with iconic political images such as this.

As a man he fought against capitalistic ideals, and has become a cultural icon. As a cultural artefact, his image on merchandise becomes a site of contention considering the moral obligations we not only have to the dead but also the living.

While debate about the evilness of Che the man remains prevalent, I conclude with the assertion that the capitalistic capture of his image for monetary gain is truly evil regardless.

References

[1] Meltzer, S. (2013). The extraordinary story behind the iconic image of Che Guevara and the photographer who took it. [online] Imaging-resource.com. Available at: https://www.imaging-resource.com/news/2013/06/06/the-extraordinary-story-behind-the-iconic-image-of-che-guevara [Accessed 11 Apr. 2019].

[2] McCormick, G. (1997). Che Guevara: The Legacy of a Revolutionary Man. World Policy Journal, [online] 14(4), pp.63-79. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40209557 [Accessed 26 Mar. 2019]. [64]

[3] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996). ‘The appeal of experience; the dismay of images: Cultural appropriations of suffering in our times.’ Daedalus, 125 (1): 1–24. [8; 1; 9; 10]

[4] Frosh, P. (2016) ‘The mouse, the screen and the Holocaust witness: Interface aesthetics and moral response’, New media and society. Sage Publications, 20(1): 351–368 [ pg.353]

[5] Lazo, O. (2016). The Story Behind Che’s Iconic Photo. [online] Smithsonian. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/iconic-photography-che-guevara-alberto-korda-cultural-travel-180960615/ [Accessed 11 Apr. 2019].

The Red Scarf: Obedience, Governance, and Bureaucracy in Chinese Primary Schools

Posted on by smisu13p

Written by Yi Li, for an assignment on ‘administrative evil’ in ANTH424, edited and published with assistance from Dr Susan Wardell.

When I was almost six, at the beginning of primary school, my teacher told me: “You are not old enough to join the Young Pioneers.” I remember feeling depressed because this meant I could not wear a red scarf (Hong Ling Jin) until the following year. It meant that I would be separated from those marked as first-class pupils.

The Red Scarf as a symbol of youth glory

Figure 1: The Book Cover of ‘Why Wear a Red Scarf?’ Published by China Children’s Press, Photo from Google Images

In China, publications for children (as per Figure 1) and political education within the schooling system, jointly construct stories about how the Chinese martyrs and heroes’ blood dyed scarves red. Once the institutional power (of political and educational structures) authorised the narrative of ‘honour’ associated with these scarves, it was taken up as a political fashion among young people. However, only the most outstanding pupils – young people aged six to fourteen – were allowed to wear the red scarves issued by the government, as part of a movement called ‘Young Pioneers of China’. Similar movements successively appeared in many Communist countries, such as North Korea and the Soviet Republic.

The motto of the Young Pioneers of China is “To fight for the cause of communism: Be ready! Always being ready!”

This reflects the socialist construction of ‘red’ emotions, such as enthusiasm and selflessness. In turn this shows how ideology informs moral values and behaviours – forming a distinctly Chinese tradition (Kleinman and Kleinman, 1985, p. 473).

This is true even for my generation, who were born in peace-time. As children, we committed to follow the notion of the Young Pioneers: to be self-disciplined, and contribute to society. In doing so we took on forms of moral behaviour that were embedded in political systems.

In this blog post I argue the ‘administrative evil’ of Young Pioneers not only produces soft violence through formal and informal rule-making and punishments, but also generates social inequality. I also argue that the process creates a ‘shadow’ in adulthood, that I reflect on as being part of the social machinery of oppression as it functions in the collective childhood of Chinese students.

Establishing the Administration: inclusion and exclusion

Figure 2: Young Pioneers Representative offered Red Scarf to Mao Zedong on 25th June 1959, in Mao’s hometown Shaoshan, Hunan province. (Photo from People.cn http://politics.people.com.cn/GB/1026/4792695.html)

In the middle of the 20th century (Figure 2), wearing a red scarf was the least privilege for very few authorised young pioneers. Two representatives (the boy and the girl next to Mao) were able to join first-class universities in Beijing once the government processed the resumption of college entrance examination in 1978. After graduation, they were expected to marry, because of this shared honour during childhood.

In contemporary primary schools (especially after the reform and opening-up policy in 1979), most pupils joined the Young Pioneers of China. To wear a red scarf on school days became everyone’s responsibility; for their class honour and individual dignity. Under the governance of senior pioneers, children’s obedience was cultivated by the ideological administration of youth glory.

Children who could not, or did not, join the young pioneers and wear red scarves became the minority among their peers (Figure 3). They would be excluded as outcasts for this. In this way, red scarves acted with authority, to include or exclude.

I vividly remember one day at school, when all my classmates shamed my desk-mate, for being the only person who had forgotten to wear the red scarf. A young ‘senior pioneer’ who was on duty deducted our class’ points, which led to us losing our status as ‘advanced’ level, in the final grade. My desk-mate was isolated by most classmates and mentors, for his accidental lapse. I remember that I remained silent, although I thought their behaviour toward him was wrong. Three months later, his father decided to transfer him to another school.

In this case, ordinary people like youth pioneers act appropriately to their organisational obligations, doing what those around them would agree they should be doing. Yet they participated in, or contributed to, what a critical and reasonable external observer might identify as morally wrong, in the distress they inflicted upon that one child.

What is administrative evil?

Social scientists Adams and Balfour (1998) deem that the technical-rational approach to social and political problems that characterises the modern age, has enabled a new and frightening form of evil. This evil is associated not with sadistic intention, but with harm caused by participation in the administration of everyday systems (Adams and Balfour, 1998, p. 13). Typically, and unlike many other forms of ethical failure, the appearance of ‘administrative evil’ is masked (Adams and Balfour, 1998). People can engage in acts of evil, unaware that they are doing so (Balfour and Alibašić, 2016).

Figure 3: Xi Jinping celebrated International Children’s Festival with Young Pioneers in Beijing Ethnicity Primary School on the 30th May 2014 (Credited by Xinhuanet, Photo from CCTV News http://news.cctv.com/2018/06/01/ARTISXoZr80oKgiYmjswGq3F180601.shtml)

As a child, I regarded the red scarf as the symbol of glory, as I was taught to do. But through this lens, as a scholar of anthropology now, I realise that it was a tool through which the children could enact and reinforce everyday systems of power, through bureaucratic systems within schools. In the harm it enacted on some children, it fits very closely with Adams and Balfour’s description of administrative evil.

Anthropologist Caton (2010, p.167) uses two philosophical concepts to unpack the idea of guilt or culpability in acts of evil: intentionality and contingency. These ideas highlight the way an anthropological analysis of evil should note the roots and contexts of actions; the role of both self-awareness (or lack thereof), and circumstance. In a similar way, Farmer (2004) proposes that anthropology of structural violence can often be understood as patterned by history, biology, and political economy (Farmer, 2004, p. 308), as well as individual ‘choice’.

Both of these views call for a holistic understanding of evil: linking macro forces to personal experience. Employing these theories is useful to examine the formation and social effect of Youth Pioneers movement, as an example of administrative power. In doing this I have also noted the rising collective nostalgia associated with red scarves, across now-adult populations.

The price of growth: collective nostalgia

Xiang Ge’s short film poster Hong Ling Jin (Red Scarf), 2011

In different historical contexts, both generations before and after the 1979 reform have been educated by the ideology of the red scarf – with wearing red scarves part of the recognition of excellence. When National leaders meet children who are honourees of the Young Pioneer programme, they do so knowing this glorious moment will be remembered (by the children, and others) as part of the chid’s lifelong glory.

For some individuals though, being deprived of the red scarf as a punishment has also become a part of the collective memory of a Chinese childhood.

Interestingly two different recent short films – Hong Ling Jin (2011) and The Red (2010) – both tell a story about boys were punished by confiscating their red scarves because they read cartoon books in classes. Under the punishment of the Young Pioneers, and under the institutions’ supervision, these actions cause the protagonists to fall into rebellion and self-doubt.

Li Xia, Cheng Teng’s animated short film The Red poster, 2010

Both of the film’s directors were born in 1980s’ China. They described their creations as part of “nostalgia”, representing their experience in primary schools.

The social media response to these films reflects a recognition that the heart-breaking moment of losing a red scarf has formed a deeply emotional part of Chinese people’s individual and collective identity. However other aspects of public discussion on social media tends to interpret their films as the “indictment of red scarves”.

Onwards

The red scarf, a symbol accompanied by a legend about political heroes, presents a vision of glory to Chinese children. Wearing a red scarf encouraged me to embody the moral emotions of communism. However the scarf as a visible sign of being a Youth Pioneer, also became the sign of privilege, and functioned to produce obedience at an early age, via reproducing established systems of governance though bureaucratic systems. It shaped our behaviour, even to the point of our participation in emotionally harming ‘divergent’ peers.

How can a child make a moral judgement, when he/she submits to the collective? For me, the red scarf is a reminder that I, like others, I have passed through the valley of administrative evil – where no one is innocent, and no one is exempt.

References:

Posted in ANTH424 (Anthropology of Evil), Case study, Media/political commentary | Tagged anthropology, behaviour, bureaucracy, childhood, China, Chinese, communism, emotion, film, governance, obediance, politics, Red Scarf, socialism, society | Leave a reply