Contrasting Evils: The raising of the Soviet flag over the Reichstag building

Written by Etienne DeVilliers, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

World War two was one of if not the most costly wars in human history. It has had ongoing significance in global spaces and memory like almost no other event in human history.

The final days of this far-reaching conflict were of particular importance to two groups; the USA and the Soviet Union. In many ways both were trying to present themselves as the hegemonic power of the future [1] with the USA pushing capitalism and the Soviet Union Communism. In particular the “race for Berlin” encapsulates this – with the USA, the French and the British approaching from the western front, and the Soviet Union approaching from the Eastern Front. In many ways, in the closing days of the war the USA were facing two enemies, the remnants of the Axis (in the Japanese and Germans) but also their supposed ally, the Soviet Union [2].

The raising of the Soviet flag over the Reichstag Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raising_a_Flag_over_the_Reichstag#/media/File:Reichstag_flag_original.jpg

An image that encapsulates this complex and nuanced state was the photo of the Raising of the flag of the Soviet Union over the Reichstag building in Berlin in 1945.

Changing meanings, shifting allegiances

The image of the flag on the Reichstag represented different thing to the two hegemonic powers of the USA and the Soviet Union. To the Americans in was a symbol of the raising of a great evil, to the Soviet Union it was a symbol of victory and revenge over an unjust enemy.

The photo itself shows 3 men raising the red flag with the hammer and sickle over the Reichstag surrounded by plumes of smoke. The photographer, Yevgeny Khaldei, stated that he was heavily inspired by the American WWII photograph of the raising of the flag on Iwo Jima, and wished to do something similar. Soviet Union sensitivities meant that Yevgeny Khaldei was not known to be the photographer for many years, the identity of the three men was also unknown until relatively recently.

The imagery present in the photo has shifted meaning drastically over time, as well as having very different meanings within different countries and political alignments.

For the Allies, the Reichstag was in many ways a symbol of their enemy – being in the past the center of German government, the building itself was symbolically constructed to symbolize a unified Germany following its unification in 1871. The Reichstag was covered with statues and images linked to Germany’s mythic past. This highlights the symbolic importance of the Reichstag despite it not being built by the Nazis it reflected much of their ideology. Due to its importance in German history, identity and politics it became a symbol to the allies to – an embodiment of Nazi Germany, and a symbol of what they fought against. This was why the Reichstag was at the center of the Soviet attack on Berlin, despite the fact that it had been a shell of its former self for about 12 years after it was burnt down in 1933.

It was in late April/early May of 1945 that the Reichstag was captured by the ‘red army’ [3]. Many soviet flags were raised on the Reichstag. Out of all the flags raised only one remains in existence today; often referred to as the Victory banner, alluding to the connections of the capturing of the Reichstag and victory within the Soviet mind-set [4]. The victory banner is used at ceremonies commemorating the end of World War 2 and has become of symbol of victory over evil.

Freedom, fascism, and the communist as liberator

Another way that the specific imagery within the photo has be construed by contemporary groups is as a symbol of “Victory over Fascism” by groups such as the international Freedom Battalion (IFB) a far left militant group fighting in places such as Syria against groups such as ISIS [5]. Below is a photograph taken by the IFB in the Syrian city of Raqqa clearly echoing the photo of the Soviet flag on the Reichstag:

The raising of a soviet flag in the Syrian city of Raqqa Source: https://external-preview.redd.it/vFh4-62I3K04F-sgB3qwrxFytHBqY3hK-9BpFYFZbXU.jpg?auto=webp&s=3b37f8dab75a94068502729d08f518d10ae26cbd

To the IFB the photograph represent victory over the evil of facism and as the flag over the Reichstag represented victory over the Nazis the flag in Raqqa to them represents a victory over the Fascism of ISIS [5]. In that regard the Flag raising of the Soviet flag fits into larger trends namely the appeal of experience [7].

This photographic reproduced advances the perception of a continuing tradition of Communists working as liberators. When questioned in regards to the photo these sentiments among IFB members become even clearer “When the red flag flew over Berlin, it was the symbol of victory over nazi-fascism. We consider Raqqa to mean the defeat of Isis-fascism and ourselves to be in the same communist tradition as the liberating troops.”[5]

However, from the perspective of the USA (and many others in the Western block) the image of the communist hammer and sickle on the Reichstag must have seemed an image of two evils: the dying evil of Nazi Germany and the raising evil of the Soviet Union.

We can see this image, showing Soviet Victory over, and the evil it evoked to the Americans, as contributing to the American decision to use the only two nuclear bombs ever used in warfare [2], in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as a display of strength in the face of their greatest rival, the Soviet Union. Yet this act can be interpreted as evil as well.

Contemporary Controversies

As the power of the Nazis waned and the cold war started with the raising of the iron curtain and the division of Berlin the image of the Soviet flag over the Reichstag would have taken on a whole new meaning, a symbol of a race lost…. as well as a symbol of the division of Berlin, and by extension Europe and the world, into the Eastern block and the Western block, separated by an ‘iron curtain’. Thus it was in the wake of the Cold War that the Soviet flag became to many a symbol of evil in a new way.

This can be seen within contemporary spaces where the Soviet flag no longer commands the political power it once did, it still conveys it. To some it represents liberation and equality but to others it still represents the great other of the Cold War as well as a great evil.

An example of the complex space in which the Soviet flag now sits, its raising at the funeral of a man who had been a communist in Stalybridge, in England in 2019 [6]. From the perspectives of the family it was honoring a relative but to the wider population of the town and wider society it was a brought forth feelings of dismay and outrage [7].

The controversial raising of a Soviet flag at a funeral in Salybridge England. Source: https://twitter.com/guidofawkes/status/972131282644856834

The outcry on social media echoed these sentiments within the population as many considered it inappropriate, following a recent suspected Russian involvement in a nerve gas attack on a journalist. This is due to the intrinsic link the Soviet flag has to Russia, and by extension its connection to the suffering inflicted on people by the Russian state.

The ideas surrounding the two evils present in the photograph of the raising of the flag over the Reichstag have not remained static through history. Rather they have be reshaped by time and by space.

In contemporary Russia the photo is a symbol of righteous revenge, and victory over Nazi Germany. For the USA its meaning has shifted, with the raising of the Iron Curtain and the pressures of the Cold War to come, as a former ally became their greatest enemy. A two very different ideologies clashed, for the USA the Flag of the Soviet Union became an evil as great as the evil incapsulated by the Reichstag itself.

References

- Wallerstein, I., 1993. The world-system after the cold war. Journal of Peace Research, 30(1), pp.1-6.

- Sherwin, M.J., 1995. Hiroshima as politics and history. The Journal of American History, 82(3), pp.1085-1093.

- Hicks, J., 2017. A Holy Relic of War: The Soviet Victory Banner as Artefact. Remembering the Second World War, pp.197-216.

- Tony, L.T.M., 2013. Race for the Reichstag: The 1945 Battle for Berlin. Routledge.

- Oak, G. 2018. A red flag over Raqqa. The Morning star retrieved from: https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/red-flag-over-raqqa

- Bugby, T. 2019. Family explains flying of Soviet flag in Stalybridge retrieved from: http://www.stalybridgecorrespondent.co.uk/2018/03/10/family-explains-flying-of-soviet-flag-in-stalybridge/

- Kleinman, A. and Kleinman, J., 1996. The appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times. Daedalus, 125(1), pp.1-23.

The Smell of Suffering: Portrait of a Street Boy

Written by Yi Li, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

Street photographers visualise social suffering through their artwork. They engage (themselves and us) with unfamiliar experiences: shrinking cities, strange portraits. Photographers can function as both moralists and anthropologists. They are often spectators, often self-exiles – presenting a version of evil for others to interpret, but often also fulfilling their own sense of moral obligation.

My argument is that both the positionality of the street photographer, and the medium of the photograph, means that photos sometimes break free from the time and space, conveying a universalism of personal adversity. I use an example of street photography of homeless in Moscow to discuss this.

Down and Out

German photographer Miron Zownir is one of the most radical contemporary examples. His focus on marginal characters and the dark side of cities is rooted in his childhood. A Ukrainian-German who grew up in post-war Germany, Zownir as a teenager immersed himself in Eastern European literature without trusting any existing political systems or social stereotypes. His inherent interest in individualists inspired him to live in slum-like places, capturing streets with an anti-establishment attitude.

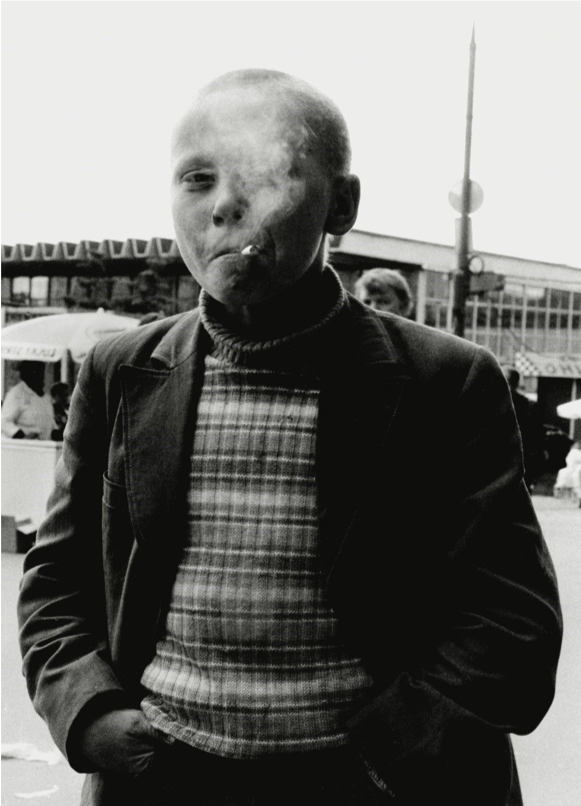

The street portrait is from Miron Zownir’s publication Down and Out in Moscow, a series of images that captured the homeless crisis in the Russian capital in 1995, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

I noticed the smoking boy with an adult expression to his cynical appearance when I first came across it in 2018. It is somehow different from the other challenging photos in his book. Momentarily, the encounter between Miron Zownir and the boy constructed a story about how individuals were abandoned by society. The diffusing cigarette smoke in front of the boy seems to allow me to smell the evil that permeated the city.

Kleinman & Kleinman (1996)[i] discuss the moral implications of photographs, through contextualising engagements within creators, audiences and images.

Zownir’s photographic experience runs through the technical transition: turning from black-and-white film to digital photography in the post-modern era. This photo was captured in a classic form, of black and white portraiture displayed in gallery spaces, and print journalism (books, and magazines). But it is worth noting that the extended agency of photographs can shift, depending on medium, from a momentary, regional realm to a worldwide standing discussion, through different forms of reprinting and representing.

How different would the viewers experience of this boy’s suffering be, scrolling past a small version in a social media feed? Touching his face on a tablet?

Moral Obligation in Street Photography: Unperceived Suffering as Social Experience

Anthropologists may ask: what is the basis of a photographer’s sense of moral obligation to take photos on streets?

Street photography concentrates on people and their behaviour in public, thereby also recording personal history: though without formal consent, and with the combination of spontaneity, outsider perspective, and private exploration. These subjects of circumstances are generally unaware – either stared at or ignored until they were documented. Street photography uses these collected narratives to define cultures or places, with no duty to serve a larger whole, and no limitation on how they reconstruct these places[ii].

Kleinman & Kleinman considered that photographers represent individual suffering as part of social experience, for others to access – whether these are extreme or ordinary forms of suffering. But as anthropologists, they caution that “there is no timeless or spaceless universal shape to suffering,” (1996, p:2).

In Down and Out in Moscow, Miron Zownir photographed death, sin, and a harsh lived reality. Underlying the powerless state, the rampantly violent proliferation pushed Moscow to become a hotbed of criminal forces in the 1990s; “the most aggressive and dangerous city, … people were dying right there on the street”.[iii] Such tension immediately changed Zownir’s original mission: to document Moscow’s nightlife with three-month project funding from a photographic committee.

Suffering is one of the existential grounds of human experience, and Kleinman & Kleinman suggest that moral witnessing also must involve a sensitivity to others, albeit with unspoken moral and political assumptions. Still functioning as a photographer, Zownir did not tend to query the government, or alter Moscow residents’ condition – but instead chose to live briefly in this shadowed twilight zone, to experience the nightmare.

Individual into the Universal: Reflexive Appreciation against the Silent Oblivion

How can we perceive a stranger’s suffering as universal? Here, a street boy’s sophisticated body language is beyond verbal expressions: dressing in a suit over a horizontal striped turtleneck sweater, his hands are hidden in his pants pockets like a social youth. He looks indifferent to the surroundings and unmoved by the photographer. He is clothed, unlike many beggars, and yet he was banished to a community where no-one had a home.

This portrait reminded me of the 1994 film In the Heat of the Sun. The film is based on Chinese writer Wang Shuo’s novel Wild Beast, which is set in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution, and tells how a teenage boy and his friends are free to roam the streets day and night in a period in which all the social and educational systems are extremely non-functional. Both protagonists are undergoing suffering – the film an example of the way their individual experiences can be abstracted and universalised, for the consumption of a wide variety of audiences. Yet this this also shows us how images and films can provide an insight into personal suffering that is usually invisible – although the harsh realities behind the lives they represent often go on unchanged.

The unwitting suffering of Zownir’s street boy is entangled with the political unrest in Moscow. But as a photograph, it also exists apart from the historical context: “a professional transformation of social life […] a constructed form that ironically naturalised experience.”[iv]

The frame itself cannot communicate this context. Yet it can communicate something else – the universality of human feeling event amidst diverse and ethically incommensurable [v] societies. Perhaps this is the power of portraiture – indeed the seminal psychological research of Ekman, and others, has asserted that emotional expression on faces is universal [vi] – meaning that moods and feelings may at times transcend cultural limitations, an idea often grappled with in the anthropology of emotion.

Conclusion: photography as a container of truth and imagination

Miron Zownir wrote in his poetry: When the earth returns with a thousand sunsets, the truth of the universal is darkness.[vii]

Photography blurs social facts, but seals emotions. Whether the boy would recognise the chaos, ignorance and madness that Zownir’s book communicates, in his free childhood in post-collapse Moscow, cannot be known. Yet seeing this photo as a cultural artefact, we can recognise that both the photographer and the audience as complicit in reproducing and politicising fragmented histories in photography. The photograph becomes a container for these forms of imagination.

Several years later after this photo was taken, when Miron Zownir was back in Moscow for his upcoming exhibition, the city’s exterior had been cleaned up. The silent responses of audiences standing in front of an enlarged version of this photograph, seemed at a vast remove from its original context. What meaning, what comfort, did it hold then? Yet the world still calls for images, as ‘the mixture of moral failures and global commerce is here to stay’ (Kleinman & Kleinman 1996: p. 7).

References:

[i] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[ii] Levy, S. (2019) ‘Street photography as a process’ in Lens Culture Guide to Street Photography, pp. 8-12

[iii] Zownir, M. (2014) ‘I was always an individualist’, Berlin Interviews, by Katerina, http://berlininterviews.com/?p=1375.

[iv] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[v] Fassin, D. (2009) ‘Beyond good and evil?: Questioning the anthropological discomfort with morals.’, Anthropological Theory. Sage, 8(4), pp. 333–344.

[vi] Ekman P, Friesen W (1976). Pictures of Facial Affect. Consulting Psychologists Press : Palo Alto.

[vii] Zownir, M. (2018) ‘Black’, Vision