The Smell of Suffering: Portrait of a Street Boy

Written by Yi Li, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

Street photographers visualise social suffering through their artwork. They engage (themselves and us) with unfamiliar experiences: shrinking cities, strange portraits. Photographers can function as both moralists and anthropologists. They are often spectators, often self-exiles – presenting a version of evil for others to interpret, but often also fulfilling their own sense of moral obligation.

My argument is that both the positionality of the street photographer, and the medium of the photograph, means that photos sometimes break free from the time and space, conveying a universalism of personal adversity. I use an example of street photography of homeless in Moscow to discuss this.

Down and Out

German photographer Miron Zownir is one of the most radical contemporary examples. His focus on marginal characters and the dark side of cities is rooted in his childhood. A Ukrainian-German who grew up in post-war Germany, Zownir as a teenager immersed himself in Eastern European literature without trusting any existing political systems or social stereotypes. His inherent interest in individualists inspired him to live in slum-like places, capturing streets with an anti-establishment attitude.

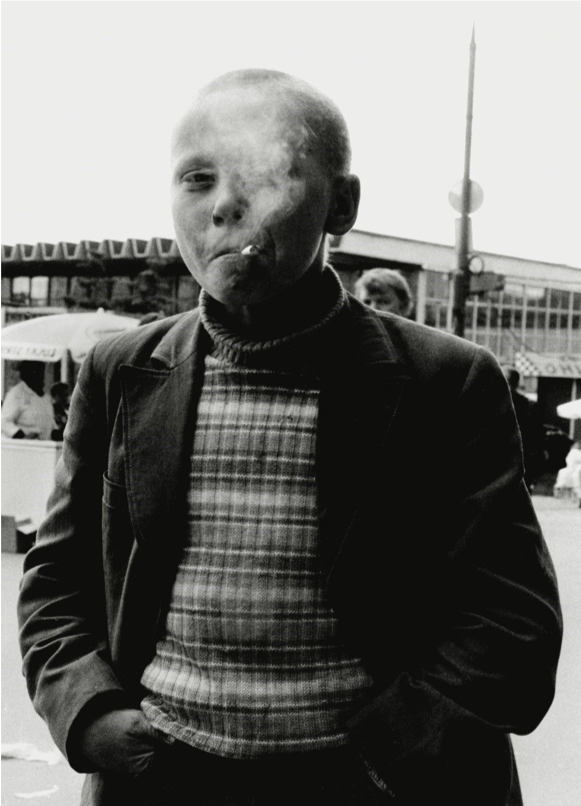

The street portrait is from Miron Zownir’s publication Down and Out in Moscow, a series of images that captured the homeless crisis in the Russian capital in 1995, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

I noticed the smoking boy with an adult expression to his cynical appearance when I first came across it in 2018. It is somehow different from the other challenging photos in his book. Momentarily, the encounter between Miron Zownir and the boy constructed a story about how individuals were abandoned by society. The diffusing cigarette smoke in front of the boy seems to allow me to smell the evil that permeated the city.

Kleinman & Kleinman (1996)[i] discuss the moral implications of photographs, through contextualising engagements within creators, audiences and images.

Zownir’s photographic experience runs through the technical transition: turning from black-and-white film to digital photography in the post-modern era. This photo was captured in a classic form, of black and white portraiture displayed in gallery spaces, and print journalism (books, and magazines). But it is worth noting that the extended agency of photographs can shift, depending on medium, from a momentary, regional realm to a worldwide standing discussion, through different forms of reprinting and representing.

How different would the viewers experience of this boy’s suffering be, scrolling past a small version in a social media feed? Touching his face on a tablet?

Moral Obligation in Street Photography: Unperceived Suffering as Social Experience

Anthropologists may ask: what is the basis of a photographer’s sense of moral obligation to take photos on streets?

Street photography concentrates on people and their behaviour in public, thereby also recording personal history: though without formal consent, and with the combination of spontaneity, outsider perspective, and private exploration. These subjects of circumstances are generally unaware – either stared at or ignored until they were documented. Street photography uses these collected narratives to define cultures or places, with no duty to serve a larger whole, and no limitation on how they reconstruct these places[ii].

Kleinman & Kleinman considered that photographers represent individual suffering as part of social experience, for others to access – whether these are extreme or ordinary forms of suffering. But as anthropologists, they caution that “there is no timeless or spaceless universal shape to suffering,” (1996, p:2).

In Down and Out in Moscow, Miron Zownir photographed death, sin, and a harsh lived reality. Underlying the powerless state, the rampantly violent proliferation pushed Moscow to become a hotbed of criminal forces in the 1990s; “the most aggressive and dangerous city, … people were dying right there on the street”.[iii] Such tension immediately changed Zownir’s original mission: to document Moscow’s nightlife with three-month project funding from a photographic committee.

Suffering is one of the existential grounds of human experience, and Kleinman & Kleinman suggest that moral witnessing also must involve a sensitivity to others, albeit with unspoken moral and political assumptions. Still functioning as a photographer, Zownir did not tend to query the government, or alter Moscow residents’ condition – but instead chose to live briefly in this shadowed twilight zone, to experience the nightmare.

Individual into the Universal: Reflexive Appreciation against the Silent Oblivion

How can we perceive a stranger’s suffering as universal? Here, a street boy’s sophisticated body language is beyond verbal expressions: dressing in a suit over a horizontal striped turtleneck sweater, his hands are hidden in his pants pockets like a social youth. He looks indifferent to the surroundings and unmoved by the photographer. He is clothed, unlike many beggars, and yet he was banished to a community where no-one had a home.

This portrait reminded me of the 1994 film In the Heat of the Sun. The film is based on Chinese writer Wang Shuo’s novel Wild Beast, which is set in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution, and tells how a teenage boy and his friends are free to roam the streets day and night in a period in which all the social and educational systems are extremely non-functional. Both protagonists are undergoing suffering – the film an example of the way their individual experiences can be abstracted and universalised, for the consumption of a wide variety of audiences. Yet this this also shows us how images and films can provide an insight into personal suffering that is usually invisible – although the harsh realities behind the lives they represent often go on unchanged.

The unwitting suffering of Zownir’s street boy is entangled with the political unrest in Moscow. But as a photograph, it also exists apart from the historical context: “a professional transformation of social life […] a constructed form that ironically naturalised experience.”[iv]

The frame itself cannot communicate this context. Yet it can communicate something else – the universality of human feeling event amidst diverse and ethically incommensurable [v] societies. Perhaps this is the power of portraiture – indeed the seminal psychological research of Ekman, and others, has asserted that emotional expression on faces is universal [vi] – meaning that moods and feelings may at times transcend cultural limitations, an idea often grappled with in the anthropology of emotion.

Conclusion: photography as a container of truth and imagination

Miron Zownir wrote in his poetry: When the earth returns with a thousand sunsets, the truth of the universal is darkness.[vii]

Photography blurs social facts, but seals emotions. Whether the boy would recognise the chaos, ignorance and madness that Zownir’s book communicates, in his free childhood in post-collapse Moscow, cannot be known. Yet seeing this photo as a cultural artefact, we can recognise that both the photographer and the audience as complicit in reproducing and politicising fragmented histories in photography. The photograph becomes a container for these forms of imagination.

Several years later after this photo was taken, when Miron Zownir was back in Moscow for his upcoming exhibition, the city’s exterior had been cleaned up. The silent responses of audiences standing in front of an enlarged version of this photograph, seemed at a vast remove from its original context. What meaning, what comfort, did it hold then? Yet the world still calls for images, as ‘the mixture of moral failures and global commerce is here to stay’ (Kleinman & Kleinman 1996: p. 7).

References:

[i] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[ii] Levy, S. (2019) ‘Street photography as a process’ in Lens Culture Guide to Street Photography, pp. 8-12

[iii] Zownir, M. (2014) ‘I was always an individualist’, Berlin Interviews, by Katerina, http://berlininterviews.com/?p=1375.

[iv] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[v] Fassin, D. (2009) ‘Beyond good and evil?: Questioning the anthropological discomfort with morals.’, Anthropological Theory. Sage, 8(4), pp. 333–344.

[vi] Ekman P, Friesen W (1976). Pictures of Facial Affect. Consulting Psychologists Press : Palo Alto.

[vii] Zownir, M. (2018) ‘Black’, Vision

Women ‘blue’ and bleeding: Witches in contemporary East Indonesia

**Originally published on the ANTH424: Anthropology of evil blog, 22nd June 2018**

Written and visual accounts of witches have changed dramatically across cultures and time. Witches were once described by Europeans in the sixteenth century as old and evil, with wrinkled and deformed features, and are now being depicted in contemporary popular culture as feminist figures who have a pale complexion, and are glamorous and beautiful [1][2]. The visual traits of contemporary witches of East Indonesia are quite distinct from what we encounter in these European historical accounts and in popular culture.

Witches, known as dukun in Indonesia have played a fundamental role in the lives of many East Indonesians, and have impacted how they structure their communities[3]. In this post I analyse how their visual traits and characteristics relate to Mary Douglas’s[4] ideas about the relationship between the body and sociality, purity and pollution. Douglas argues that the body is a symbol of society that requires order and classification, and by referring to East Indonesian witches, one can distinguish this.

In some areas of East Indonesia, there are no distinct visual traits that set apart witches within their communities. Konstantinos Retsikas ethnography [3] concerning sorcery in East Java, Indonesia, noted that both the instigator and the sorcerer remain hidden in fear of being killed. People can only rely on rumours and whispered accusations to identify witches within East Java. As a witch, blending in is the safest approach. At the same time, they share the same motives of envy, greed and jealousy that is common in everyone, challenging people’s ability to accurately recognise the witches within their community.

In some areas of East Indonesia, there are no distinct visual traits that set apart witches within their communities. Konstantinos Retsikas ethnography [3] concerning sorcery in East Java, Indonesia, noted that both the instigator and the sorcerer remain hidden in fear of being killed. People can only rely on rumours and whispered accusations to identify witches within East Java. As a witch, blending in is the safest approach. At the same time, they share the same motives of envy, greed and jealousy that is common in everyone, challenging people’s ability to accurately recognise the witches within their community.

Although due to this lack of distinct visual traits, Retsikas found that in East Java sorcery accusations always tend to focus on one’s relatives, neighbours, friends and work colleagues. Convivial intimacy is risky and choosing one’s friends wisely is critical. Hence, their unidentifiable traits protect some witches, but also leads to uncertainty and moral panic amongst the people of East Java. The unmarked body of witches impacts the communities ability to keep things pure and in order, affecting how members of East Java respond to one another in times of conflict. Thus, this reflects on Douglas’s idea concerning how the body, whether marked or unmarked, is a key symbol in identifying how a community functions.

A key trait prominent in Kodi female hereditary witches from the coastal villages of Sumba is their association with “blue arts” [5].

In Janet Hoskins ethnography, she recognised the transformation of Kodi women into witches led to the appearance of the shade blue in and around their body. As she mentioned, “Hereditary witches have “blueness in them”, they are “bluish people” (tou morongo) whose very blood is believed to be in some way poisonous to others… Blueness is said to be deep inside the liver (ela ate dalo) of a witch, a kind of poison that can affect others even without her willing it” [5]: 322. This poisonous trait is a reflection of pollution and signifies the darkness within hereditary witches. When they are exposed to this powerful trait that can harm the community and their formal structure, it pushes witches into the margins. “Blue arts” or “blueness” found internally and externally in hereditary witches sets them apart from other Kodi women, making them vulnerable to discrimination by their community, and powerful at the same time. Thus, their polluting body has the potential to disrupt the communities social structure and create fear amongst people.

Menstrual blood is a powerful characteristic associated with witchcraft.

Both Konstantinos Retsikas and Janet Hoskins ethnographic study explore the significance of menstrual blood and how the substance has impacted how some villages in East Indonesia function today. In the Huaulu community, Hoskins found that they have strict menstrual taboos to protect their people. Menstruating women are required to stay in menstruating huts away from the men until their cycle has finished. Menstrual blood is believed to be a dangerous and contaminating substance of witches, and can lead to men becoming extremely ill if they come in contact with it. Hence, Huaulu women accept this menstrual taboo as it is seen as a way of protecting the men within their community, and keeps their village pure and clean.

Huaulu strict taboo and the significance of menstrual blood for many other East Indonesian villages relates to Mary Douglas’s idea about the relationship between the body and sociality, purity and pollution. According to Douglas, “The body is a model which can stand for any bounded system”[4]: 115. The bounded system in Huaulu expresses anxiety about the body and its fluids, while at the same time it administers care and protection for the group. Some argue that specific parts of the body, particularly menstrual blood symbolises “dirt [that] offends against order”[4]: 2. Although in Huaulu, their community members are effectively engaging with this polluted and “dirty” substance by creating strict taboos around it, leading to the development of relationships and the strengthening of social order. Therefore, the significance of menstrual blood and its association with witches impacts how Indonesians culturally construct their communities.

Although there are no distinct traits that set apart Indonesian witches in some areas, they continue to play a fundamental role for numerous citizens. Their presence within key substances, and power to cause positive change and conflict within one’s life does not go unnoticed. At the same time, their features relate to Mary Douglas’s ideas of the relationship between the body and sociality, purity and pollution in many ways, affecting how people of East Indonesia function in contemporary society.

Written by: Pulegaomalo Muliagatele-Carter

References:

[1] Briggs 2002: p.15 in Mencej, M. (2007) ‘7- Social Witchcraft: Village Witches’. In: Styrian Witches in European Perspective: Ethnographic Fieldwork, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 313-346.

[2] Buckley, C. (2017) ‘Witches in Popular Culture’. [online]. The Open University. Available from: http://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/literature/witches-popular-culture. [Accessed 14 June 2018].

[3] Retsikas, K. (2010) ‘The Sorcery of Gender: Sex, Death and Difference in East Java, Indonesia’. South East Asia Research, 18(3), pp. 471-502.

[4] Douglas, M. (1966) Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge and K. Paul.

[5] Hoskins, J. (2002) ‘The Menstrual Hut and The Witch’s Lair in Two Eastern Indonesian Societies.’ Ethnology, 41(4), pp. 317-333.

The Red Scarf: Obedience, Governance, and Bureaucracy in Chinese Primary Schools

Posted on by smisu13p

Written by Yi Li, for an assignment on ‘administrative evil’ in ANTH424, edited and published with assistance from Dr Susan Wardell.

When I was almost six, at the beginning of primary school, my teacher told me: “You are not old enough to join the Young Pioneers.” I remember feeling depressed because this meant I could not wear a red scarf (Hong Ling Jin) until the following year. It meant that I would be separated from those marked as first-class pupils.

The Red Scarf as a symbol of youth glory

Figure 1: The Book Cover of ‘Why Wear a Red Scarf?’ Published by China Children’s Press, Photo from Google Images

In China, publications for children (as per Figure 1) and political education within the schooling system, jointly construct stories about how the Chinese martyrs and heroes’ blood dyed scarves red. Once the institutional power (of political and educational structures) authorised the narrative of ‘honour’ associated with these scarves, it was taken up as a political fashion among young people. However, only the most outstanding pupils – young people aged six to fourteen – were allowed to wear the red scarves issued by the government, as part of a movement called ‘Young Pioneers of China’. Similar movements successively appeared in many Communist countries, such as North Korea and the Soviet Republic.

The motto of the Young Pioneers of China is “To fight for the cause of communism: Be ready! Always being ready!”

This reflects the socialist construction of ‘red’ emotions, such as enthusiasm and selflessness. In turn this shows how ideology informs moral values and behaviours – forming a distinctly Chinese tradition (Kleinman and Kleinman, 1985, p. 473).

This is true even for my generation, who were born in peace-time. As children, we committed to follow the notion of the Young Pioneers: to be self-disciplined, and contribute to society. In doing so we took on forms of moral behaviour that were embedded in political systems.

In this blog post I argue the ‘administrative evil’ of Young Pioneers not only produces soft violence through formal and informal rule-making and punishments, but also generates social inequality. I also argue that the process creates a ‘shadow’ in adulthood, that I reflect on as being part of the social machinery of oppression as it functions in the collective childhood of Chinese students.

Establishing the Administration: inclusion and exclusion

Figure 2: Young Pioneers Representative offered Red Scarf to Mao Zedong on 25th June 1959, in Mao’s hometown Shaoshan, Hunan province. (Photo from People.cn http://politics.people.com.cn/GB/1026/4792695.html)

In the middle of the 20th century (Figure 2), wearing a red scarf was the least privilege for very few authorised young pioneers. Two representatives (the boy and the girl next to Mao) were able to join first-class universities in Beijing once the government processed the resumption of college entrance examination in 1978. After graduation, they were expected to marry, because of this shared honour during childhood.

In contemporary primary schools (especially after the reform and opening-up policy in 1979), most pupils joined the Young Pioneers of China. To wear a red scarf on school days became everyone’s responsibility; for their class honour and individual dignity. Under the governance of senior pioneers, children’s obedience was cultivated by the ideological administration of youth glory.

Children who could not, or did not, join the young pioneers and wear red scarves became the minority among their peers (Figure 3). They would be excluded as outcasts for this. In this way, red scarves acted with authority, to include or exclude.

I vividly remember one day at school, when all my classmates shamed my desk-mate, for being the only person who had forgotten to wear the red scarf. A young ‘senior pioneer’ who was on duty deducted our class’ points, which led to us losing our status as ‘advanced’ level, in the final grade. My desk-mate was isolated by most classmates and mentors, for his accidental lapse. I remember that I remained silent, although I thought their behaviour toward him was wrong. Three months later, his father decided to transfer him to another school.

In this case, ordinary people like youth pioneers act appropriately to their organisational obligations, doing what those around them would agree they should be doing. Yet they participated in, or contributed to, what a critical and reasonable external observer might identify as morally wrong, in the distress they inflicted upon that one child.

What is administrative evil?

Social scientists Adams and Balfour (1998) deem that the technical-rational approach to social and political problems that characterises the modern age, has enabled a new and frightening form of evil. This evil is associated not with sadistic intention, but with harm caused by participation in the administration of everyday systems (Adams and Balfour, 1998, p. 13). Typically, and unlike many other forms of ethical failure, the appearance of ‘administrative evil’ is masked (Adams and Balfour, 1998). People can engage in acts of evil, unaware that they are doing so (Balfour and Alibašić, 2016).

Figure 3: Xi Jinping celebrated International Children’s Festival with Young Pioneers in Beijing Ethnicity Primary School on the 30th May 2014 (Credited by Xinhuanet, Photo from CCTV News http://news.cctv.com/2018/06/01/ARTISXoZr80oKgiYmjswGq3F180601.shtml)

As a child, I regarded the red scarf as the symbol of glory, as I was taught to do. But through this lens, as a scholar of anthropology now, I realise that it was a tool through which the children could enact and reinforce everyday systems of power, through bureaucratic systems within schools. In the harm it enacted on some children, it fits very closely with Adams and Balfour’s description of administrative evil.

Anthropologist Caton (2010, p.167) uses two philosophical concepts to unpack the idea of guilt or culpability in acts of evil: intentionality and contingency. These ideas highlight the way an anthropological analysis of evil should note the roots and contexts of actions; the role of both self-awareness (or lack thereof), and circumstance. In a similar way, Farmer (2004) proposes that anthropology of structural violence can often be understood as patterned by history, biology, and political economy (Farmer, 2004, p. 308), as well as individual ‘choice’.

Both of these views call for a holistic understanding of evil: linking macro forces to personal experience. Employing these theories is useful to examine the formation and social effect of Youth Pioneers movement, as an example of administrative power. In doing this I have also noted the rising collective nostalgia associated with red scarves, across now-adult populations.

The price of growth: collective nostalgia

Xiang Ge’s short film poster Hong Ling Jin (Red Scarf), 2011

In different historical contexts, both generations before and after the 1979 reform have been educated by the ideology of the red scarf – with wearing red scarves part of the recognition of excellence. When National leaders meet children who are honourees of the Young Pioneer programme, they do so knowing this glorious moment will be remembered (by the children, and others) as part of the chid’s lifelong glory.

For some individuals though, being deprived of the red scarf as a punishment has also become a part of the collective memory of a Chinese childhood.

Interestingly two different recent short films – Hong Ling Jin (2011) and The Red (2010) – both tell a story about boys were punished by confiscating their red scarves because they read cartoon books in classes. Under the punishment of the Young Pioneers, and under the institutions’ supervision, these actions cause the protagonists to fall into rebellion and self-doubt.

Li Xia, Cheng Teng’s animated short film The Red poster, 2010

Both of the film’s directors were born in 1980s’ China. They described their creations as part of “nostalgia”, representing their experience in primary schools.

The social media response to these films reflects a recognition that the heart-breaking moment of losing a red scarf has formed a deeply emotional part of Chinese people’s individual and collective identity. However other aspects of public discussion on social media tends to interpret their films as the “indictment of red scarves”.

Onwards

The red scarf, a symbol accompanied by a legend about political heroes, presents a vision of glory to Chinese children. Wearing a red scarf encouraged me to embody the moral emotions of communism. However the scarf as a visible sign of being a Youth Pioneer, also became the sign of privilege, and functioned to produce obedience at an early age, via reproducing established systems of governance though bureaucratic systems. It shaped our behaviour, even to the point of our participation in emotionally harming ‘divergent’ peers.

How can a child make a moral judgement, when he/she submits to the collective? For me, the red scarf is a reminder that I, like others, I have passed through the valley of administrative evil – where no one is innocent, and no one is exempt.

References:

Posted in ANTH424 (Anthropology of Evil), Case study, Media/political commentary | Tagged anthropology, behaviour, bureaucracy, childhood, China, Chinese, communism, emotion, film, governance, obediance, politics, Red Scarf, socialism, society | Leave a reply