Why might this box of ‘Lopchu’ tea – found in a Dunedin kitchen cupboard a few months ago – cause a historian of the Kalimpong scheme to get very excited?

In the last blog we learnt about a Presbyterian scheme that arranged for the resettlement of adolescent Anglo-Indians in Dunedin in the early 20th century. Those migrants all grew up in a residential school in Kalimpong, in Northeast India.

But where were they originally from?

Exploring the life story of one of those migrants allows us to understand the larger drivers of the Kalimpong scheme, and the extraordinary trajectories of families caught up in the expansion of the British Empire and development of the tea industry.

George Langmore’s childhood was typical of the ‘Kalimpong Kids’ who were sent to Dunedin. Born on a tea plantation in Darjeeling to a British tea planter and a Nepali tea worker, for the first few years of his life George occupied the privileged but relatively free life of the planter’s child on a large estate – living in the bungalow, cared for by his mother and an ayah (Indian nanny), mixing with the various ethnic groups who worked on the plantation, and likely picking up several languages along the way.

As idyllic as it may sound to us today, this kind of childhood would have caused considerable concern to his father. Interacting with local workers, speaking local languages, roaming around the crops and ‘jungle’, and befriending children on the plantation – these were all seen as a threat to British children’s racial status. While it is tempting to be critical of the tea planters’ actions in sending their children away from the plantation, the letters written by these men to staff of the Homes have revealed their affection for their children and difficulty in parting with them.

George was sent to the Homes in Kalimpong in 1903, when he was eight years old, and there he stayed until his arrival in Dunedin with a small group in 1911. Like all of the boys from Kalimpong he was placed on a local farm. George later secured work as an attendant at Seacliff, an asylum north of Dunedin, a position he held for more than twenty years. In 1918 George married Ellen Percy. He took Ellen to India in 1927, where they visited Kalimpong and the tea estate where he was born.

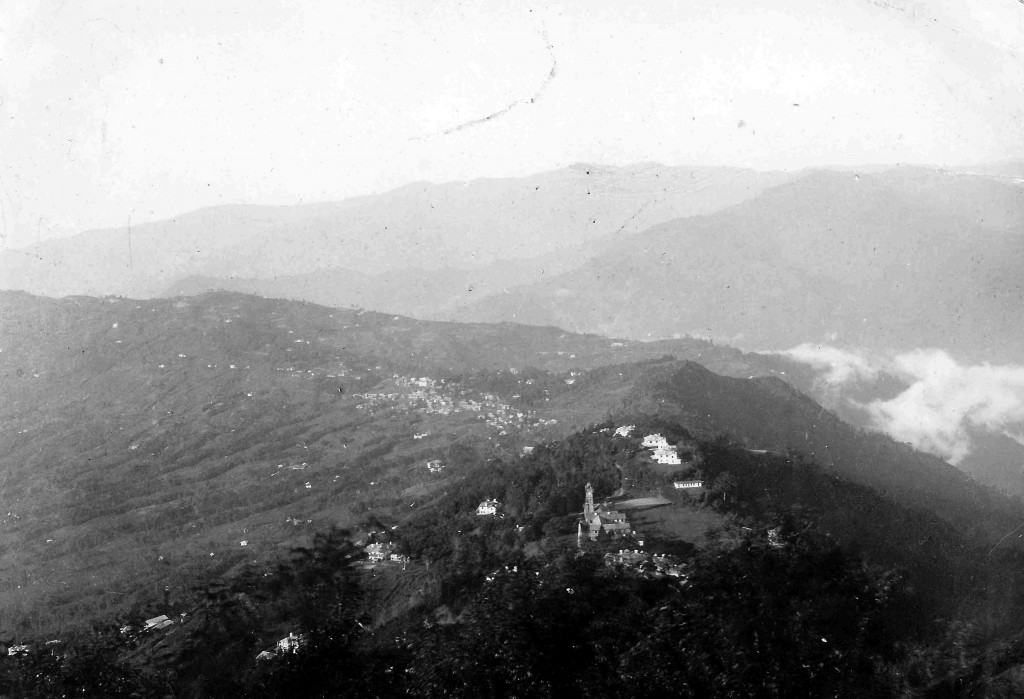

St Andrew’s Colonial Homes (foreground) and Kalimpong township (background). Photograph taken by George Langmore in 1927, and kindly supplied by the Langmore family.

George and Ellen had two daughters, and settled in Musselburgh. In 1937 John Graham, founder of the Homes, visited New Zealand with the aim of meeting again all of his graduates living there. For his week in Dunedin he stayed with George, who took him around the city to find the various graduates living here.

Graham wrote in his diary that George ‘must have done well’, noting two features of the Langmore home that attested to George’s global heritage: the fine carpets in the house were from Glasgow, and there was a sign on the gate that said ‘Lopchu Villa’. Lopchu was the name of his father’s tea estate in Darjeeling.

In their later years, many Kalimpong emigrants were reluctant to talk about their Indian heritage. But they have left clues that descendants have followed, often all the way back to Kalimpong and the tea plantations of Assam and Darjeeling.

George Langmore was relatively open about his connections to India. His descendants remember his love of cooking Indian food, and his unwillingness to settle for an ordinary cup of tea – he sourced tea (and pickles!) from India, mixing together a blend of different teas to get a ‘good cuppa’.

Beneath these quiet connections to their places of birth, the Kalimpong emigrants have held close their stories of separation from their imperial families. Archival research has enabled many descendants to reconnect with relatives in Britain, but there is little chance of tracing the maternal line of these tea plantation families.

Jane McCabe

References

http://kalimpongkids.org.nz/

Diary of John Graham, 1937, Kalimpong Papers, National Library of Scotland.

Iris McFarlane, Daughters of the Empire. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Roy Moxham, Tea: Addiction, Exploitation and Empire. New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, 2003.

Special thanks to the Langmore family for providing photographs and biographical details for George Langmore.