The Carisbrook Crusade

Superstar evangelist Dr. Billy Graham electrifies Dunedin in 1969

Carisbrook, 9 March 1969: Under a threatening clouds, twenty thousand spectators brace against the cold wind, wrapped in blankets and travelling rugs. Many have come from beyond Dunedin, by bus from smaller regional centres and still more by train from Invercargill and Christchurch. A group of Canadians and Americans, as well as a party from the North Island arrived by air earlier in the week. Present also is the minister of broadcasting, the Hon. L. R. Adams-Schneider and mayor of Dunedin Mr. J. G. Barnes. At this point, the event might be fairly mistaken for a big rugby match, save for the fact that rugby games never end with over one thousand people, eighty percent aged under twenty-five, publicly coming forward to accept Christ. This was the first and last Dunedin crusade of American evangelist Dr. Billy Graham.

Looking down on Bill Graham at the ‘Brook. J.D. Douglas, “A Tale of Two Islands,” Decision, May 1969, 8, in Roy Nelson McKenzie, “Billy Graham Crusade Newsletters 1967-1969”, 2012/18/6, DE 7/5, The Presbyterian Research Centre (PCANZ), Knox College, Dunedin.

Dr Graham’s career as an international evangelist stretched back to the mid 1940s, where his rousing speech and commanding personality transformed the humble open-air sermon into phenomenally successful mass rallies. A decade before his visit in the flesh, Graham had reached out to Dunedin via landline: his 1959 crusades in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch were relayed in real time to crowded meetings in urban and rural centres around the country, reaching over 185,000 New Zealanders in addition to the tens of thousands who personally attended his rallies. Having conducted major crusades throughout Africa, Europe, Britain, South America, Asia and the United States, by the time he personally appeared at Carisbrook a decade later, Graham was the world’s best-known evangelist.

Dr Billy Graham and his crusade team arrive aboard the “Gospel Train” at Caversham station. J.D. Douglas, “A Tale of Two Islands,” Decision, May 1969, 8 in Roy Nelson McKenzie, “Billy Graham Crusade Newsletters 1967-1969”, 2012/18/6, DE 7/5, The Presbyterian Research Centre (PCANZ), Knox College, Dunedin.

Evangelical Protestantism in New Zealand was, in turn, part of a worldwide movement that took hold in the post-war years, breathing new life into a tradition inherited from 1730s Britain by her colonies. From 1949, Billy Graham was a unifying figure in this modern movement that was built on the long-standing evangelical emphasis on justification by faith and in the primacy of the Bible. Earlier in the century Dunedin had seen the mass missions of R.A. Torrey and J. Wilbur Chapman: pre-campaign preparation, prayer meetings, the kindling of emotion with large choirs and audience participation, calculated build ups of tension, public affirmations and “follow ups” through counselling or decision cards were all well-established tactics. However, revival methods took on a new flavour in the late fifties and sixties as popular culture and mass entertainment established the compelling power of celebrity status, the exploitation of new travel networks and a mastery of modern technology as central elements of the crusade arsenal.

A rush forward. New converts join counsellors at the conclusion of the crusade – signing decision cards, receiving bible study booklets and giving their names to local church representatives. J.D. Douglas, “A Tale of Two Islands,” Decision, May 1969, 9 in Roy Nelson McKenzie, “Billy Graham Crusade Newsletters 1967-1969”, 2012/18/6, DE 7/5, The Presbyterian Research Centre (PCANZ), Knox College, Dunedin.

International air travel enabled Graham and his crusade team to conduct 419 crusades in 185 countries and territories over the course of his 58-year career. He preached before 84 million people, and reached an additional 215 million via radio, television and landline relay. While Dunedin missed out on the full impact of Graham’s presence in 1959, landline relay meetings were still successful in bring his message to Otago. New Zealanders like the rest of the world, were becoming accustomed to experiencing from afar via the latest technologies. A branch of Graham’s association, World Wide Pictures, produced impressive, full-length feature films such as “Souls in Conflict” (1954) and “For Pete’s Sake” (1969), which were used alongside footage from previous campaigns as to build interest for the crusade. These “commendable instruments of evangelism” were a hit in Dunedin: in just three screenings at His Majesty’s Theatre, Souls in Conflict was seen by 3,600 people, including many from out of town. Audiences would begin arriving up to an hour and a half before the screenings to secure a seat and many were turned away. This was 1956, over a decade before Graham’s visit and a sure sign of things to come.

However, modernity also brought worries: the Cold War, materialism, the sexualised threat of rock n’ roll, disintegration of families and a plague of foul-mouthed bodgies and widgies filling the country’s milk bars gave Graham’s message tremendous currency. To Dunedin audiences, he emphasised that the world would face catastrophe if morality was allowed to fall by the wayside, despite the technological wonders of the new age. The answer lay in Christian rebirth and devoted service to the Lord, which Graham invited his audience to undertake by stepping forward after the sermon and giving their name to one of the 600 counsellors waiting in front of the official dais. The involvement of local ministers, the Crusade Choir & solo singing by George Beverly Shea softened the gravity of Graham’s message.

The logic behind this approach had been explained to a meeting of minsters and theological students at Knox college the previous afternoon: “To communicate the gospel there must be a contagious excitement about Christ. There is little feeling in the church, it is too cold, too hard, too logical- emotion is an essential part of a crusade”. Graham’s newfangled methods, his emphasis on the power of the emotions, the universal applicability of the gospel, and the requirement for an individualistic decision to become a Christian retained a heavy presence in New Zealand ministry from the late 1950s to the 1960s, contributing to the growth of evangelical style parishes around the country. Though brief, the Carisbrook Crusade lingered in local memory for years to come – placing evangelical innovation and energy squarely in the public eye, and reflecting an undeniable drift towards new forms of Christianity in Dunedin and throughout the Western World.

Violeta Gilabert

Sources:

“Billy Graham Crusade Newsletters 1967-1969”, 2012/18/6, DE 7/5, The Presbyterian Research Centre (PCANZ), Dunedin.

Bryan D. Gilling, “‘Back to the Simplicities of Religion’: The 1959 Billy Graham Crusade in New Zealand and its Precursors.” Journal of Religious History, Vol. 17, No. 2, December 1992.

Stuart M. Lange, A Rising Tide: Evangelical Christianity in New Zealand, 1930-1965. (Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2013).

Judith Smart, “The Evangelist as Star: The Billy Graham Crusade in Australia 1959”, Journal of Popular Culture, June 1999.

The ‘Wisdom Religion’ in Dunedin

With the founding of our local Lodge of the Theosophical Society in 1893, Asian religions and traditions loomed large in the spiritual and intellectual lives of some Dunedinites.

‘Servants of the Star, 17 Dowling St., 1919-1920’. The Dunedin chapter of the Servants of The Star, a Theosophical youth organisation, with Miss Agnes Inglis, an influential Dunedin Theosophist, on the right. Dunedin Theosophical Society Collection.

Asian places, peoples and practices shaped and reshaped colonial society, playing an important part in the making of “New Zealand culture” as we know it today. Dunedin’s Theosophical Society provides a strong example of this trend: the Society brought the “oriental renaissance” to Otago as it members saw opportunities for intellectual stimulation and spiritual revivification in Asian religious traditions. Concepts such as karma, samsara (reincarnation) and nirvana offered new ways of thinking about the nature of life and its meaning. Theosophists were especially attracted to the “ancient wisdom” they believed was stored in important Indian texts like the Vedas and the Bhagavad-Gita. More generally, they were very interested in comparative religion and were deeply committed to the ‘universal brotherhood of humanity without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste, or colour’.

Initially founded in New York city in 1875, the Theosophical Society quickly emerged as a prominent international movement. Local branches or lodges flourished across the globe in the 1880s and the 1890s: the first New Zealand lodge was established in Wellington in 1888. Local lodges organised reading groups, discussion circles and public lectures and provided members with access to library collections and reading rooms. Effectively, the Lodges were sites where books, ideas and arguments were exchanged. Theosophists in New Zealand were part of a global association: they were part of the Australasian Section of the Society and built strong connections to the Theosophical Society’s international networks which had a wide reach from Adyar, in the Indian city of Madras, which became the Society’s headquarters.

Presbyterianism was a powerful influence on the development of early Dunedin, but the city also was home to a significant cohort of freethinkers and individuals interested in new religious movements, such as Theosophy. The first Dunedin name to appear on the international role of the Theosophical Society’s membership was that of Augustus William Maurais, the son of a London bookseller who arrived in Otago in 1875 and became prominent as a journalist, editor and newspaperman. His early years as a Theosophist in Dunedin were lonely ones until a chance meeting with wealthy tannery owner Grant Farquhar, who Maurais noticed on the train from Sawyers Bay to Dunedin reading a Theosophical magazine. In 1893 Maurais and Farquhar were joined as founding members of the Dunedin branch of the Theosophical Society by Robert Pairman, Frank Allan, John Oddie and Thomas Ross: their newly-established Lodge was the third in New Zealand to have a charter issued. From the 1890s, women were actively involved in the Dunedin Lodge and held a range of offices, including the position of President.

‘The Hartley Family c. 1900’, Muir & Moodie. Local pianist and music teacher John K. Hartley and his family are representative of the middle class, intellectual character of Dunedin’s early Theosophists. Dunedin Theosophical Society Collection

Although the Society’s selective approach to new membership meant that it grew slowly – with 18 members in 1896 and 39 in 1900 – its interest in non-western religions caused considerable anxiety. Dunedin’s newspapers showed a persistent interest in both the Society’s international programme and its local growth. The Evening Star ran an “exposé” column written by a London correspondent, the Otago Daily Times closely followed the activities of prominent Theosophist Annie Besant, while The Triad printed a detailed account of Theosophy with the explanation that there was so much public interest in Theosophy that this new movement could be no longer ignored. The Christian Outlook, edited by the influential Presbyterian minister and social reformer Rutherford Waddell, resentfully commented on the ‘excitement; Theosophy had induced in Dunedin.

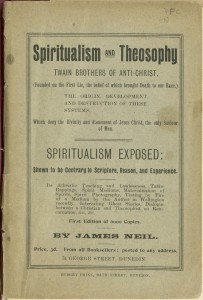

James Neil, a local chemist, produced a pamphlet Spiritualism and Theosophy Twain Brothers of the Anti-Christ that summarised the hostility that some Dunedinites felt towards this new movement: by synthesising the “ancient wisdom” of the Holy Bible with the Vedas, the Bhagavad Gita and the Koran, Neil judged Theosophy guilty of reducing “Jesus to the level of man” and “the Bible to the level of other books”. To Neil and many other Christians in Dunedin, the interest of the city’s Theosophists in the “heathen faiths” of India was a threat to the authority of the Bible, the Protestant churches, and the morality of the colony.

Although the Dunedin Lodge of the Theosophical Society remained small, until World War One it was particularly prominent in Dunedin’s intellectual and cultural life, feeding debates over a range of issues from karma to astrology, vegetarianism to the value of “occult” knowledge. Interest in these areas was in part generated by the visits of prominent Theosophists from overseas – Mrs Cooper Oakley in 1893, Annie Besant in 1894 and 1908, the Countess Wachmeister in 1895 and Colonel Olcott in 1897 – whose public lectures grew significant audiences and stimulated further controversy.

The Dunedin Lodge persisted through these public arguments and continued to support its members in exploring ancient texts and new ways of looking at the world. It also provided an important source of fellowship and sociability for a cluster of Dunedin families as well as visitors.

‘T.S. Convention, Picnic at Broad Bay, 1917’. A picnic at Broad Bay, 1917. Wm. Augustus Maurais, founding member and dedicated champion of Theosophy in Dunedin can be seen centre-left, standing with hands clasped. Dunedin Theosophical Society Collection.

Many Dunedinites will remember the impressive turreted building the Lodge occupied at 236 High Street (after moving from its earlier location in leased rooms in Dowling Street). Having just taken up residence in the old Fitzroy Hotel building on Hillside Road, the Dunedin Theosophical Society Lodge, one of city’s most enduring cultural institutions, is showing no sign of slowing down.

Violeta Gilabert

References:

A.Y. Atkinson, ‘The Dunedin Theosophical Society, 1892-1900’, BA Hons Dissertation, University of Otago, 1978.

Tony Ballantyne, ‘India in New Zealand’, in his Webs of Empire: Locating New Zealand’s Colonial Past, Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 2012, 82-104.

James Neil, Spiritualism and Theosophy Twain Brothers of the Anti-Christ, Dunedin: Budget Print, c.1901. (A copy is held in Hocken Collections).

Further InformatIon: