Thomas Reid and the dangers of introspection

Juan Gomez writes…

In the upcoming symposium we are hosting here at the University of Otago, I will be giving a paper on the features of the experimental method in moral philosophy (you can read the abstract). One of the salient features of this method was the use of introspection as a tool to access the nature and powers of the human mind. In fact, some Scottish moral philosophers acknowledge introspection as the only way we can get to know the nature of our mind. George Turnbull and David Fordyce were proponents of such claims, as well as Thomas Reid. The latter, in the Introduction to his Inquiry into the Human Mind (1764) draws an analogy with anatomy where he tells us that, in the same way we gain knowledge of the body by dissecting and observing it, we must perform an ‘anatomy of the mind’ to “discover its powers and principles.” The problem is that unlike the anatomist who has multiple bodies to observe, the anatomist of the mind can only look into his own mind:

- It is his own mind only that he can examine with any degree of accuracy and distinctness. This is the only subject he can look into.

Reid notices that this is not good for our experimental inquiry into the human mind, since a general law or rule cannot be deduced from just one subject:

- So that, if a philosopher could delineate to us, distinctly and methodically, all the operations of the thinking principle within him, which no man was ever able to do, this would be only the anatomy of one particular subject; which would be both deficient and erroneous, if applied to human nature in general.

But this obstacle doesn’t persuade Reid to give up introspection (Reid uses the term ‘reflection’) since it is “the only instrument by which we can discern the powers of the mind.” What we have to do is be very careful:

- It must therefore require great caution, and great application of mind, for a man that is grown up in all the prejudices of education, fashion, and philosophy, to unravel his notions and opinions, till he find out the simple and original principles of his constitution… This may be truly called an analysis of the human faculties; and, till this is performed, it is in vain we expect any just system of the original powers and laws of our constitution, and an explication from them to the various phaenomena of human nature.

Scottish moral philosophers were faced with this dilemma. On one hand, in order to access the nature of the human mind, they had to rely on a tool that could only examine and observe one particular mind, making the generalization of the principles discovered impossible; on the other hand, introspection was the only way to access the human mind, since by observing others we cannot gain any knowledge of what goes on in their minds, at least not accurately. The solution, consistent with the spirit of the experimental method, was to focus only on what we can experience and observe, and follow this evidence only as far as it can take us. Therefore as Reid points out, we are to use reflection with

- caution and humility, to avoid error and delusion. The labyrinth may be too intricate, and the thread too fine, to be traced through all its windings; but, if we stop where we can trace it no farther, and secure the ground we have gained, there is no harm done; a quicker eye may in time trace it farther.

These comments by Reid show that even when the problems of relying on introspection were explicitly recognized, the Scottish moral philosophers still used it as their way to access the nature of the human mind. Since introspection was considered to be the only reliable way into the workings of the human mind, they had to be very careful with the use they made of it. This caution was achieved by following the methodology of the experimental method, where they could only go as far as their observations would take them, and their conclusions had to be confirmed by the particular experience of many. But such limits to the conclusions drawn from introspection cast doubt on the status of the exercise of reflection: could introspection really be considered ‘experimental,’ or was the justification given by the moral philosophers (Reid in particular) just a rhetorical device? This is a problem that requires a lot more space than a blog post, but if you have any particular thoughts and comments I am looking forward to receiving and discussing them with you.

Experimental Philosophy and the Origins of Empiricism: Symposium Abstracts

Hello, readers!

Below are the abstracts of the papers that we will discuss at the upcoming symposium on experimental philosophy and the origins of empiricism. The symposium will take place at the University of Otago in Dunedin, NZ, on the 18th and 19th of April and you can find the programme here.

If you would like to attend but have not registered yet, drop an email to Peter. Attendance is free, but we’d like to have an idea of how many people are coming. If you cannot attend, but are interested in some of the papers, let Alberto know. We are happy to circulate them in advance and would love to hear your comments. Also, check this blog in the weeks after the symposium. We will post discussions and commentaries on the papers. We’re looking forward to extend our discussions to the blog. We might also post the video of one of our sessions if we manage to.

Peter Anstey, The Origins of the Experimental-Speculative Distinction

This paper investigates the origins of the distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy (ESP) in the mid-seventeenth century. It argues that there is a significant prehistory to the distinction in the analogous division between operative and speculative philosophy, which is commonly found in late scholastic philosophy and can be traced back via Aquinas to Aristotle. It is argued, however, the ESP is discontinuous with this operative/speculative distinction in a number of important respects. For example, the latter pertains to philosophy in general and not to natural philosophy in particular. Moreover, in the late Renaissance operative philosophy included ethics, politics and oeconomy and not observation and experiment – the things which came to be considered constitutive of the experimental philosophy. It is also argued that Francis Bacon’s mature division of the sciences, which includes a distinction in natural philosophy between the operative and the speculative, is too dissimilar from the ESP to have been an adumbration of this later distinction. No conclusion is drawn as to when exactly the ESP emerged, but a series of important developments that led to its distinctive character are surveyed.

Related posts: Who invented the Experimental Philosophy?

Juan Gomez, The Experimental Method and Moral Philosophy in the Scottish Enlightenment

One of the key aspects, perhaps the most important one, of the enlightenment in Great Britain is the scientifically driven mind set of the intellectuals of the time. This feature, together with the emphasis of the importance of the study of human nature gave rise to the ‘science of man.’ It was characterized by the application of methods used in the study of the whole of nature to inquiries about our own human nature. This view is widely accepted among scholars, who constantly mention that the way of approaching moral philosophy in the eighteenth century was by considering it as much a science as natural philosophy, and therefore the methods of the latter should be applied to the former. Nowhere is this more evident than in the texts on moral philosophy by the Scottish intellectuals. But despite the common acknowledgement of this feature, the specific details and issues of the role of the experimental method within moral philosophy have not been fully explored. In this paper I will explore the salient features of the experimental method that was applied in the Scottish moral philosophy of the enlightenment by examining the texts of a range of intellectuals.

Related posts: Turnbull and the ‘spirit’ of the experimental method; David Fordyce’s advice to students.

Peter Anstey, Jean Le Rond d’Alembert and the Experimental Philosophy

If the experimental/speculative distinction provided the dominant terms of reference for early modern philosophy before Kant, one would expect to find evidence of this in mid-eighteenth-century France amongst the philosophes associated with Diderot’s Encyclopédie project. Jean Le Rond d’Alembert’s ‘Preliminary Discourse’ to the Encyclopedie provides an ideal test case for the status of the ESP in France at this time. This is because it is a methodological work in its own right, and because it sheds light on d’Alembert’s views on experimental philosophy expressed elsewhere as well as the views of others among his contemporaries. By focusing on d’Alembert and his ‘Discourse’ I argue that the ESP was central to the outlook of this philosophe and some of his eminent contemporaries.

Kirsten Walsh, De Gravitatione and Newton’s Mathematical Method

Newton’s manuscript De Gravitatione was first published in 1962, but its date of composition is unknown. Scholars have attempted to date the manuscript, but they have not yet reached a consensus. There have been two main attempts to date De Gravitatione. Hall & Hall (1962) argue for an early date of 1664 to 1668, but no later than 1675. Dobbs (1991) argues for a later date of late-1684 to early-1685. Each side lists handwriting analysis and various conceptual developments as evidence.

In the first part of this paper, I examine the evidence provided by these two attempts. I argue that the evidence presented provides a lower limit of 1668 and an upper limit of 1684. In the second part of this paper, I compare De Gravitatione‘s two-pronged methodology with the mathematical method in Newton’s early optical papers composed between 1672 and 1673. I argue that the two-pronged methodology of De Gravitatione is a more sophisticated version of the mathematical method used in Newton’s early optical papers. Given this new evidence, I conclude that Newton probably composed De Gravitatione after 1673.

Related posts: Newton’s Method in ‘De gravitatione’

Alberto Vanzo, Experimental Philosophy in Eighteenth Century Germany

The history of early modern philosophy is traditionally interpreted in the light of the dichotomy between empiricism and rationalism. Yet this distinction was first developed by Kant and his followers in the late eighteenth century. Many early modern thinkers who are usually categorized as empiricists associated themselves with the research program of experimental philosophy and labelled their opponents speculative philosophers. Did Kant and his followers know the tradition of experimental philosophy and the historical distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy? If so, what prompted them to introduce the historiographical distinction between empiricism and rationalism?

To answer these questions, the first part of the paper focuses on Christian Wolff, the most influential German philosopher of the first half of the eighteenth century. It is argued that Wolff developed his philosophy in a way that was orthogonal to the experimental-speculative distinction. The second part of the paper argues that the distinction experimental-speculative distinction was known and widely used by Kant’s contemporaries from the 1770s to the end of the century. It is concluded that Kant and his followers were well aware of experimental philosophy. Their choice not to focus on the ESD must have been a deliberate one.

Related posts: Experiment and Hypothesis, Theory and Observation: Wolff vs Newton; Tetens on Experimental vs Speculative Philosophy

Alberto Vanzo, Empiricism vs Rationalism: Kant, Reinhold, and Tennemann

Many scholars have criticized histories of early modern philosophy based on the dichotomy of empiricism and rationalism. Among the reasons for their criticism are:

- The epistemological bias: histories of philosophy which give pride of place to the rationalism-empiricism distinction (RED) overestimate the importance of epistemological issues for early modern philosophers.

- The Kantian bias: histories of early modern philosophy that embrace the RED are often biased in favour of Immanuel Kant’s philosophy. They portray Kant as the first author who uncovered the limits of rationalism and empiricism, rejected their mistakes, and incorporated their correct insights within his Critical philosophy.

- The classificatory bias: histories of philosophy based on the RED tend to classify all early modern philosophers prior to Kant into either the empiricist, or the rationalist camps. However, these classifications have proven far from convincing.

After summarizing Kant’s discussions of empiricism and rationalism, the paper argues that Kant did not have the classificatory, Kantian, and epistemological biases. However, he promoted a way of writing histories of philosophy from which those biases would naturally flow. It is argued that those biases can be found in the early Kant-inspired historiography of Karl Leonhard Reinhold and Wilhelm Gottlieb Tennemann.

Related posts: Kant, Empiricism, and Historiographical Biases; Reinhold on Empiricism, Rationalism, and the Philosophy without Nicknames

Thanks to Wordle for the word cloud above.

Who invented the Experimental Philosophy?

Peter Anstey writes…

Sometimes the question ‘Who invented X?’ has no determinate answer, in spite of claims of particular individuals. One thinks of questions like ‘Who invented the internet?’ and the various dubious claims to this honour. Christoph Lüthy has argued quite convincingly that ‘the microscope was never invented’ (Early Science and Medicine, 1, 1996, p. 2). I suggest that the same probably goes for the experimental philosophy: there is no single person or group of people who created it, rather it somehow ‘emerged’ in Europe sometime between the death of Francis Bacon in 1626 and the founding of the Royal Society in 1660. One place to look for answers is to trace the early uses of the term ‘experimental philosophy’.

Here is the evidence that I am aware of for the emergence of the term ‘experimental philosophy’ in early modern England. The first English work to use the term ‘experimental philosophy’ according to EEBO was Robert Boyle’s Spring of the Air in 1660. Interestingly, the term philosophia experimentalis had already appeared in the title of Nicola Cabeo’s Latin commentary on Aristotle’s Meteorology of 1646 and Boyle cites Cabeo’s book twice in Spring of the Air. The first English book to use the term in its title was Abraham Cowley’s A Proposition for the Advancement of Experimental Philosophy of 1661. From then on, however, books about experimental philosophy start to roll off the presses of England. Boyle’s Usefulness of Experimental Natural Philosophy and Henry Power’s Experimental Philosophy, both published in 1663, got the ball rolling. (Incidentally, Cabeo’s book was reprinted in Rome in 1686 under the title Philosophia experimentalis.) As for manuscript sources, the earliest use of the term ‘experimental philosophy’ that I have found is in Samuel Hartlib’s Ephemerides in 1635.

Another place to look for evidence for the inventor of the experimental philosophy is in discussions of natural philosophy and of experiment. It appears that Francis Bacon never used the term ‘experimental philosophy’, but he did develop a conception of experientia literata (learned experience), which might be thought to be a precursor of the experimental philosophy. This appears in Book 5 of his De augmentis scientiarum of 1623, where it is distinguished from interpretatio naturae (interpretation of nature). The experientia literata is a method of discovery proceeding from one experiment to another, whereas interpretatio naturae involves the transition from experiments to theory. But this doesn’t resemble the distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy very closely. For example, the experimental philosophy was, on the whole, opposed to speculation and hypotheses and there is no sense of opposition or tension in Bacon’s distinction.

Furthermore, a distinction between operative (or practical) and speculative philosophy was commonplace in scholastic divisions of knowledge in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, and this, no doubt provided the basic dichotomy on which the experimental/speculative distinction was based. But the operative/speculative distinction doesn’t map very well onto the experimental/speculative distinction, not least because by ‘operative sciences’ the scholastics meant ethics, politics and oeconomy (that is, management of society) and not observation and experiment.

Who invented the experimental philosophy? I don’t think that there is a determinate answer to this question, but I’m happy to be corrected and am keen for suggestions as to where to look for more evidence.

Newton’s Method in ‘De gravitatione’

Kirsten Walsh writes…

Newton’s manuscript De Gravitatione (‘De Grav.’ for short) was published for the first time in 1962, but no one knows when it was written. Some scholars have argued that Newton wrote De Grav. as early as 1664, others, as late as 1685, and there have been arguments for almost every period in between.

Ostensibly, the topic of De Grav. is “the science of the weight and of the equilibrium of fluids and solids in fluids”. Newton discusses this topic in the form of definitions, axioms, propositions, corollaries, and finally a scholium. However, the scholium ends abruptly and the manuscript is unfinished. One of the most notable features of this manuscript is what Hall & Hall describe as a “structural failure”: what begins as a brief discussion of a definition turns into a lengthy and detailed attack on the Cartesian conception of space and time. This digression is significant. Firstly, it is useful for understanding the development of Newton’s thoughts on many topics. Secondly, it supports the view that, in Principia, Newton’s intended opponent was Cartesian, rather than Leibnizian.

In this post, I am not going to talk about Newton’s 23-page digression (which may well form the basis of another post). Rather, I am interested in the opening paragraph of this manuscript, in which Newton describes his method. He begins:

- “It is fitting to treat the science of the weight and of the equilibrium of fluids and solids in fluids by a twofold method.”

The first, he tells us, is a geometrical method. He says he plans to demonstrate his propositions “strictly and geometrically” by:

- Abstracting the phenomena from physical considerations;

- Establishing a strong foundation of definitions, axioms and postulates; and

- Formulating lemmas, propositions and corollaries.

The second is a natural philosophical method. He says he plans to explicate and confirm the certainty of his propositions by the use of experiments. He says that these discussions will be restricted to scholia, to ensure that the two methods are kept separate.

This twofold method bears striking resemblance to two other aspects of Newton’s work:

- It accurately describes the method and structure of Principia; and

- It resembles the quasi-mathematical method he uses to ‘prove’ his theory of colours.

The first point is uncontroversial – almost boring, given how many times it has been mentioned in the literature. But it shows that this method is in use by Newton at least by the mid-1680s. My second point, however, requires some explanation.

In an earlier post I argued that, at least in the early 1670s, Newton’s goal is absolute certainty. He hopes to achieve certainty in the science of colours by making it ‘mathematical’. The clearest demonstration of his quasi-mathematical method is found in Newton’s reply to Huygens, where he sets out his theory of colours in a series of definitions and propositions, in the style of a geometrical proof.

Despite the resemblance, this is not precisely the same method that Newton is advocating in De Grav. Experiment appears to play a different role.

In his early optical work, propositions are founded on experiment. So experiment should be the first step in any inquiry. For example, in a letter written in 1673, Newton says:

- “I drew up a series of such Expts on designe to reduce the Theory of colours to Propositions & prove each Proposition from one or more of those Expts by the assistance of common notions set down in the form of Definitions & Axioms in imitation of the Method by which Mathematicians are wont to prove their doctrines.”

But in De Grav., Newton says that experiment is employed to ‘illustrate and confirm’ the propositions. That is, experiment is supposed to occur as a later step.

This raises several questions about Newton’s methodology. Is there any practical difference between the two methods? Does this represent a significant shift in the role Newton assigned to experiment? Can methodology shed any light on the dating of De Grav.? What do you think?

Next week, we’ll hear from Peter Anstey.

Reinhold on Empiricism, Rationalism, and the Philosophy without Nicknames

Alberto Vanzo writes…

There is a traditional way of narrating the development of early modern philosophy. I first studied it in high school and no doubt you are familiar with it. According to this narrative, the central dispute within early modern philosophy concerned epistemological matters:

- Do we have a priori knowledge of the world?

- Do we have innate concepts?

Rationalists answered that we do, whereas empiricists denied it. Eventually came Kant, who refuted empiricists and rationalists, sentenced the end of those movements, and embodied their insights within his own transcendental philosophy.

These days, this sort of narrative is regularly attacked for overstating the importance of epistemological matters and for being biased in favour of Kant’s philosophy. Who first framed that narrative? Some say it was Kant. Yet I argued in an earlier post that this is not the case. While Kant introduces the terms “empiricism” and “rationalism”, he does not view empiricism and rationalism as purely epistemological views. Moreover, he does not take his thought to be above empiricism and rationalism. He takes himself to be a rationalist.

Karl Leonhard Reinhold

Karl Leonhard Reinhold first spelled out the traditional historiographical framework in works from the early 1790s (such as On the Foundation of Philosophical Knowledge and the Contributions toward Correcting the Previous Misunderstandings of Philosophers, from which I will quote). In these years, Reinhold was articulating his own system, “Elementary Philosophy”. He distinguished it from Kant’s philosophy with these words:

- The Elementary Philosophy is therefore essentially different from the Critique of Pure Reason. And the philosophy of which it is a part […] can no more be called critical than it can empirical, rationalist or sceptical. It is philosophy without nicknames.

At this point, Reinhold makes some bold historiographical claims:

- The insufficiency of empiricism brought about rationalism, and the insufficiency of the latter sustained the other in turn. Humean scepticism unveiled the insufficiency of both of theses dogmatic systems, and thus occasioned Kantian criticism. The latter overturned one-sided dogmatism and dogmatic skepticism.

How did this all happen? First came Locke’s empiricism and Leibniz’s rationalism:

- The two philosophers laid down, one in the simple representations drawn from experience and the other in innate representations […], the only foundation of philosophical knowledge possible for the empiricists [on the one hand] and the rationalists [on the other.] And while their followers were busy disagreeing about the external details and the refinements of their systems, David Hume came along

and revealed their mistake. This was believing that we are able to know mind-independent things, either on the basis of simple mental representations drawn from experience (empiricism), or by means of innate concepts and principles (rationalism).

- Hume confronted this crucial issue about the conformity of impressions to their objects; this was what everybody had taken for granted without proof before his time, and he demonstrated that no proof can be offered that is without contradiction.

Hume’s mistake was assuming, like Locke and Leibniz, that the objects that impressions must conform to be true are mind-independent or, in Kant’s terms, things in themselves. Kant rejected that “groundless assumption by proving “that objective truth is entirely possible without knowledge of things in themselves”. Reinhold’s Kant takes objective truth to be the correspondence of our mental representations with mind-dependent, phenomenal objects. On the basis of this view, Kant answered the central question of what are the extension and limits of our cognitive powers. For Reinhold, answering this question enabled Kantians to solve the disputes in the fields of ethics and natural law, and even theology.

With his account, Reinhold places Kant above and beyond empiricism and rationalism. Reinhold takes epistemological issues on the foundation and limits of knowledge to be central to the whole philosophy of early modern age. In short, Reinhold has the epistemological and Kantian biases.

It is easy to see why Reinhold’s potted history of early modern philosophy was attractive for Reinhold’s contemporaries. From a historiographical point of view, it places four works that Reinhold’s contemporaries held in great esteem (Locke’s Essay, Leibniz’s New Essays, Hume’s Treatise, and Kant’s first Critique) within a single, coherent narrative. From a philosophical point of view, Reinhold places Kantian and post-Kantian philosophies that had become increasingly popular at the summit of the development of human reason.

Reinhold’s history of early modern philosophy is very sketchy. The first historian to flesh it out in great detail was Wilhelm Gottlieb Tennemann. Next time I will tell you about him.

Paintings as Experiments in Natural and Moral Philosophy

Juan Gomez writes…

About a month ago I published a post on George Turnbull’s Treatise on ancient Painting. There I briefly commented that Turnbull thought that paintings could work as proper samples or experiments for natural and moral philosophy (understood as the ‘science of man’). I want to expand on this issue in this post.

The whole of Turnbull’s Treatise, as he comments at the beginning of chapter seven, is designed to show the usefulness of the imitative arts for philosophy and education in general. After a recollection of the thoughts of the ancient philosophers on these arts, Turnbull dedicates the last two chapters of the book to sketch the reasons for incorporating the arts in the Liberal education program. This is where paintings can serve as samples or experiments.

To understand the role of paintings, it is necessary to point out a general characteristic of Turnbull’s philosophy. He believed that human beings were made to contemplate and to imitate nature, and their happiness was mainly achieved through these two activities. If we take a look and examine all our faculties and powers, we will see that we are perfectly constituted for the study of nature. We acquire knowledge through the observation of nature, and the desire to imitate it leads us to perform experiments that will enhance our understanding of it.

Nature is also the source for the work of the artist:

- The Artist derives all his Ideas from Nature, and does not make Laws and Connexions agreeably to which he works in order to produce certain Effects, but conforms himself to such as he finds to be necessarily and unchangeably established in Nature. (Treatise on Ancient Painting, p. 137)

From this it follows that the paintings of an artist should represent (imitate) nature as it is in reality, following all its laws. With this in mind Turnbull goes on to tell us that paintings in fact serve as samples or experiments for natural and moral philosophy:

- Philosophy is rightly divided into natural and moral; and in like manner, Pictures are of two Sorts, natural and moral: The former belong to natural, and the other to moral Philosophy. For if we reflect upon the End and Use of Samples or Experiments in Philosophy, it will immediately appear that Pictures are such, or that they must have the same Effect. What are Landscapes and Views of Nature, but Samples of Nature’s visible Beauties, and for that Reason Samples and Experiments in natural Philosophy? And moral Pictures, or such as represent parts of human Life, Men Manners, Affections, and Characters; are they not Samples of moral Nature, or of the Laws and Connexions of the moral World, and therefore Samples or Experiments in moral Philosophy? (Treatise, p. 145)

Since the paintings are supposed to represent nature, it is impossible to appreciate them without comparing them to the original (reality). In this sense paintings will provide us with a proper sample of nature that will enhance our knowledge of it. Turnbull’s theory relies on the artist making exact ‘copies’ of nature, and only then can they serve as proper samples. In the case of natural pictures, he allows two sorts of ‘copies’: either exact representations of nature (like a photograph), or imaginary scenes, as long as they conform to the Laws of Nature. If they are not in these categories, then they shouldn’t be taken as proper samples for the study of nature, and in Turnbull’s case, not even as good works of art. Those works of art that do not imitate nature do not give us the pleasure derived from those that do.

Turnbull prescribes a parallel form of realism for moral paintings. These pictures should depict human nature as it really is, and through them we can gain knowledge of our actions and characters:

- Moral Pictures, as well as moral Poems, are indeed Mirrours in which we may view our inward Features and Complexions, our Tempers and Dispositions, and the various Workings of our Affections. ‘Tis true, the Painter only represents outward Features, Gestures, Airs, and Attitudes; but do not these, by an universal Language, mark the different Affections and Dispositions of the Mind? (Treatise, p. 147)

As long as the sole purpose of the arts is to imitate nature, and all the works follow the laws of nature (even in cases of imaginary scenes), Turnbull can count them as having the same effect ‘real’ samples and experiments have.

Locke’s Master-Builders were Experimental Philosophers

Peter Anstey says…

In one of the great statements of philosophical humility the English philosopher John Locke characterised his aims for the Essay concerning Human Understanding (1690) in the following terms:

- The Commonwealth of Learning, is not at this time without Master-Builders, whose mighty Designs, in advancing the Sciences, will leave lasting Monuments to the Admiration of Posterity; But every one must not hope to be a Boyle, or a Sydenham; and in an age that produces such Masters, as the Great – Huygenius, and the incomparable Mr. Newton, with some other of that Strain; ’tis Ambition enough to be employed as an Under-Labourer in clearing Ground a little, and removing some of the Rubbish, that lies in the way to Knowledge (Essay, ‘Epistle to the Reader’).

Locke regarded his project as the work of an under-labourer, sweeping away rubbish so that the ‘big guns’ could continue their work. But what is it that unites Boyle, Sydenham, Huygens and Newton as Master-Builders? It can’t be the fact that they are all British, because Huygens was Dutch. It can’t be the fact that they were all friends of Locke, for when Locke penned these words he almost certainly had not even met Isaac Newton. Nor can it be the fact that they were all eminent natural philosophers, after all, Thomas Sydenham was a physician.

In my book John Locke and Natural Philosophy, I contend that what they had in common was that they all were proponents or practitioners of the new experimental philosophy and that it was this that led Locke to group them together. In the case of Boyle, the situation is straightforward: he was the experimental philosopher par excellence. In the case of Newton, Locke had recently reviewed his Principia and mentions this ‘incomparable book’, endorsing its method in later editions of the Essay itself. Interestingly, in his review Locke focuses on Newton’s arguments against Descartes’ vortex theory of planetary motions, which had come to be regarded as an archetypal form of speculative philosophy.

In the case of Huygens, little is known of his relations with Locke, but he was a promoter of the method of natural history and he remained the leading experimental natural philosopher in the Parisian Académie. In the case of Sydenham, it was his methodology that Locke admired and, especially those features of his method that were characteristic of the experimental philosophy. Here is what Locke says of Sydenham’s method to Thomas Molyneux:

- I hope the age has many who will follow [Sydenham’s] example, and by the way of accurate practical observation, as he has so happily begun, enlarge the history of diseases, and improve the art of physick, and not by speculative hypotheses fill the world with useless, tho’ pleasing visions (1 Nov. 1692, Correspondence, 4, p. 563).

Note the references to ‘accurate practical observation’, the decrying of ‘speculative hypotheses’ and the endorsement of the natural ‘history of diseases’ – all leading doctrines of the experimental philosophy in the late seventeenth century. So, even though Sydenham was a physician, he could still practise medicine according to the new method of the experimental philosophy. In fact, many in Locke’s day regarded natural philosophy and medicine as forming a seamless whole in so far as they shared a common method. It should be hardly surprising to find that Locke held this view, for he too was a physician.

If it is this common methodology that unites Locke’s four heroes then we are entitled to say ‘Locke’s Master-Builders were experimental philosophers’. I challenge readers to come up with a better explanation of Locke’s choice of these four Master-Builders.

Galileo and Experimental Philosophy

Greg Dawes writes…

In a recent conference paper I have argued that in some key respects Galileo’s natural philosophy anticipates the experimental philosophy of the later seventeenth century. I am not claiming that Galileo uses the term “experimental philosophy.” Nor do I claim that he makes any distinction comparable to that between experimental and speculative natural philosophy. His Italian followers in the Accademia del Cimento would later do so, but he does not. Nonetheless, the way in which Galileo undertakes natural philosophy displays at least two of the features that Peter Anstey and his collaborators have argued are characteristic of experimental philosophy.

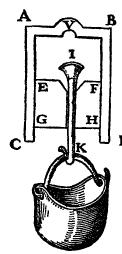

Galileo's sketch of a device to demonstrate the power of a vacuum.

The first of these has to do with the role of experiment. Much of the twentieth-century debate centred on whether Galileo actually performed the experiments about which he writes. But the more important question has to do with the role of experiments in Galileo’s thought. Like his Aristotelian predecessors, Galileo seeks to construct a demonstrative natural philosophy: one in which the conclusions follow with certainty from the premises. But unlike the Aristotelian, he relies on geometrical proofs. Like any mathematical proofs, these can be elaborated in an a priori fashion, without any reference to experience. But whether a particular proof applies to the world of experience – or, better still, whether it accurately describes the structure of the world – can only be ascertained experimentally. It is experiment which tells us which geometrical proof is to be used, even if the geometrical proof itself can be developed independently of experience. (I am relying here on the work of Martha Féher, Peter Machamer, and others.)

Perhaps more importantly, Stephen Gaukroger has argued that experimentation shaped the very way in which Galileo’s physical theories are framed and formulated. Alexander Koyré and others have argued that the laws of Galilean physics are “abstract” laws which refer to an ideal reality. It is true, of course, that in setting aside “impediments” (impedimenti), such as the resistance of the air, Galileo’s proofs do not refer to the world of everyday experience. But it is unhelpful to think of them as an idealisations of, or abstractions from, experienced reality. There is an experienced reality to which they conform. It may not be that of everyday experience, but it is that of carefully controlled physical experiments. It follows that in Galileo’s work, the task of natural philosophy is being rethought. It is no longer the study of reality as revealed to everyday observation; it is the study of that reality revealed in experimental situations.

The second way in which Galileo’s natural philosophy anticipates the later experimental philosophy is in its comparative lack of interest in the mechanisms thought to underlie phenomena. It is not that Galileo was a positivist in our modern sense. There are passages in which he engages in speculation regarding matter theory and on these occasions he favours a corpuscularian view. But such speculations are, as Salviati says in the Two New Sciences, a mere “digression.” Galileo does not consider that his new science requires them. Indeed his work on motion is almost entirely a kinematics – as he freely admits, it says nothing about the causes of motion – but Galileo does not consider it any less significant as a result.

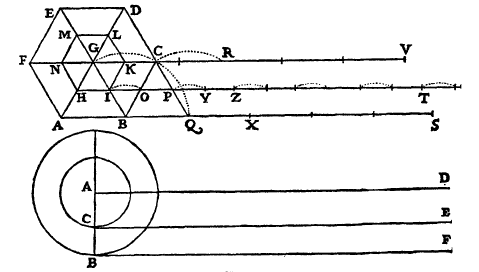

Galileo's solution of the "rota Aristotelis" paradox, demonstrating that a body could be composed of an infinite number of unquantifiable atoms.

This should not be interpreted as a general lack of interest in causation, as Stillman Drake suggests. Galileo shares the ancient desire cognoscere rerum causas (to know the causes of things). But the causal properties Galileo seeks are different from those sought by his predecessors. His causes are the mathematically describable properties of the objects whose behaviour is being explained, properties that no Aristotelian would regard as essential. (Even his atoms are more akin to mathematical points than physical objects.) It is, once again, experimentation that allows us to pick up which of those mathematically describable properties are generally operative and therefore the proper subject of a science. It is this move that allows Galileo, as it would later allow Newton, to be content with a causal account that remains on the level of phenomena, rather than speculating about a realm inaccessible to observation.

In an early dialogue, Galileo has two rustics (contadini) speculating about the new star of 1605. One of them advises his companion to listen to the mathematicians rather than the philosophers, for they can measure the sky the way he himself can measure a field. It doesn’t matter of what material the heavens are made. “If the sky were made of polenta,” he says, “couldn’t they still see it alright?” This is surely something new in the history of natural philosophy.

Postscript:

While I would still defend the individual claims contained here, my continued study of Galileo has made me increasingly cautious about the usefulness of a distinction between experimental and speculative natural philosophy. It is certainly the case that many late seventeenth-century thinkers made such a distinction, but is it a useful one for us to make? I’m not confident that it is.

Experiment certainly played an important role in Galileo’s work, although precisely what that role was continues to be contested. And it is true that Galileo has little interest in speculating about the underlying structure of the world: even if, as he writes, the sky were made of polenta, the mathematicians could still measure it. The problem is that the classical, mathematical tradition out of which he comes — that of astronomy, statics, optics, and (after Galileo) the study of local motion — cannot be helpfully characterized as either experimental or speculative. It certainly uses experiment, but it also reasons a priori, in ways that seem independent of experience.

So perhaps it would be better to have a threefold classification of early modern scientific traditions. (A classification of this kind is suggested by Casper Hakfoort in the last chapter of his Optics in the Age of Euler.) A first tradition would be that of matter theory, which is inevitably speculative insofar as it deals with matters not accessible to direct observation. (This is the realm of Newton’s “hypotheses.”) Corpuscularian proposals would fall into this category, as would Descartes’s vortex theory. A second tradition would be that of experimental natural philosophy, which regarded the results of experiment as themselves significant forms of knowledge, whether or not they could be connected with an underlying theory of the nature of matter. Finally, there is the mathematical tradition that Galileo transformed, so successfully, by producing a mathematical account of local motion.

Individual natural philosophers could engage in all three kinds of activities, but will differ according to the emphasis they place on one or other of them. So although Galileo certainly engaged in experiments, his emphasis was on the kind of reasoning characteristic of the mathematical tradition. It is this form of reasoning, I have come to believe, that cannot be easily fitted into the experimental-speculative scheme.

Newton’s Early Queries are not Hypotheses

Kirsten Walsh writes…

In an earlier post I demonstrated that, in his early optical papers, Newton is working with a clear distinction between theory and hypothesis. Newton takes a strong anti-hypothetical stance, giving theories higher epistemic status than hypotheses. Newton’s corpuscular hypothesis appears to challenge his commitment to this anti-hypothetical position. Today I will discuss a second challenge to this anti-hypotheticalism: Newton’s use of queries.

Newton’s queries have often been interpreted as hypotheses-in-disguise. But in his early optical papers, Newton’s queries are not hypotheses. In fact, he is building on the method of queries prescribed by Francis Bacon, for whom assembling queries is a specific step in the acquisition and development of natural philosophical knowledge.

To begin, what is Newton’s method of queries? In a letter to Oldenburg, Newton explains that

- “the proper Method for inquiring after the properties of things is to deduce them from Experiments.”

Having obtained a theory in this way, one should proceed as follows: (1) specify queries that suggest experiments that will test the theory; and (2) carry out those experiments.

He then lists eight queries relating to his theory of light and colours, e.g.:

- “4. Whether the colour of any sort of rays apart may be changed by refraction?

“5. Whether colours by coalescing do really change one another to produce a new colour, or produce it by mixing onely?”

He ends the letter, saying:

- “To determin by experiments these & such like Queries which involve the propounded Theory seemes the most proper & direct way to a conclusion. And therefore I could wish all objections were suspended, taken from Hypotheses or any other Heads than these two; Of showing the insufficiency of experiments to determin these Queries or prove any other parts of my Theory, by assigning the flaws & defects in my Conclusions drawn from them; Or of producing other Experiments which directly contradict me, if any such may seem to occur. For if the Experiments, which I urge be defective it cannot be difficult to show the defects, but if valid, then by proving the Theory they must render all other Objections invalid.”

While Newton’s method of queries is experimental, it does not appear to be strictly Baconian. For the Baconian-experimental philosopher, queries serve “to provoke and stimulate further inquiry”. Thus, for the Baconian-experimental philosopher, queries are part of the process of discovery. However, for Newton, queries serve to test the theory and to answer criticisms. Thus, they are part of the process of justification.

Newton uses queries to identify points of difference between his theory and its opponents. For example, in a letter to Hooke he writes:

- “I shall now in the last place proceed to abstract the difficulties involved in Mr Hooks discourse, & without having regard to any Hypothesis consider them in general termes. And they may be reduced to these three Queries. [1] Whether the unequal refractions made without respect to any inequality of incidence, be caused by the different refrangibility of several rays, or by the splitting breaking or dissipating the same ray into diverging parts; [2] Whether there be more then two sorts of colours; & [3] whether whitenesse be a mixture of all colours.”

And in a letter to Huygens, Newton says:

- “Meane time since M. Hu[y]gens seems to allow that white is a composition of two colours at least if not of more; give me leave to rejoyn these Quæres.

“1. Whether the whiteness of the suns light be compounded of the like colours?

“2. Whether the colours that emerg by refracting that light be those component colours separated by the different refrangibility of the rays in which they inhere?”

In both cases, Newton is using queries to steer the debate towards claims that can be tested and resolved by experiment. On both occasions, Newton devotes a considerable amount of space to discussing the experiments that might determine these queries.

These early queries are not hypotheses. Rather, they are empirical questions that may be resolved by experiment. This is not merely a matter of semantics. In the same letter to Hooke, Newton demonstrates this by distinguishing between philosophical queries and hypothetical queries. A philosophical query is one that can be determined by experiment, a hypothetical query cannot. Newton argues that philosophical queries are the only acceptable queries. He equates hypothetical queries with begging the question.

In his later work, Newton’s queries become increasingly speculative, suggesting that they function as de facto hypotheses. Does Newton ultimately reject his early ‘method of queries’?

Next Monday we’ll have a guest post from Greg Dawes on Galileo and the Experimental Philosophy.

Symposium on Experimental Philosophy and the Origins of Empiricism

St Margaret’s College, University of Otago, 18-19 April 2011

Monday 18 April

9.00 Introductory Session (Peter Anstey and Alberto Vanzo)

9.30 Discussion of Peter Anstey, The Origins of the Experimental/Speculative Distinction

Discussant: Gideon Manning

Chair: Alberto Vanzo

11:30 Discussion of Juan Gomez, The Experimental Method and Moral Philosophy in the Scottish Enlightenment

Discussant: Charles Pigden

Chair: Kirsten Walsh

14:30 Discussion of Kirsten Walsh, De Gravitatione and Newton’s Mathematical Method

Discussant: Keith Hutchison

Chair: Philip Catton

20:00 European Panel of Experts (video conference)

Chair: Peter Anstey

Tuesday 19 April

9:30 Discussion of Peter Anstey, Jean Le Rond d’Alembert and the Experimental Philosophy

Discussant: Anik Waldow

Chair: Juan Gomez

11:30 Discussion of Alberto Vanzo, Empiricism vs Rationalism: Kant, Reinhold, and Tennemann

Discussant: Tim Mehigan

Chair: Philip Catton

14:30 Discussion of Alberto Vanzo, Experimental Philosophy in Eighteenth Century Germany

Discussant: Eric Watkins

Chair: Peter Anstey

16:30 Final plenary session, led by Gideon Manning

17:00 Conclusion

Attendance at the symposium is free. However, space is limited, so we advise you to register early. To register and for information, please email peter.anstey@otago.ac.nz.

Abstracts of all papers are available here. If you cannot attend, but would like to read some of the papers, send us an email.