Experimental Philosophy: Old and New

Over the last few months, we have been working with Dr Donald Kerr, the Special Collections Librarian at the University of Otago, to prepare a rare book exhibition on the history of experimental philosophy. We have brought together classic works of the past and cutting-edge books of the present, to illustrate the theme of experimental philosophy as it was understood and practised 350 years ago and as it is understood today.

- Our exhibition, ‘Experimental Philosophy: Old and New’, was launched a few weeks ago, to coincide with the annual conference of the Australasian Association of Philosophy (AAP). It will run until 23 September 2011, so if you are coming to Dunedin, be sure to stop by and see it.

For those who cannot come to Dunedin, we are thrilled to announce the launch of the online version of our exhibition. Notable items on display include a second edition of Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1713), Francis Bacon’s Of the Advancement Learning (1640), poet Abraham Cowley’s ‘A Proposition for the Advancement of Experimental Philosophy’ (1668), and an exciting new discovery* concerning the philosopher David Hume!

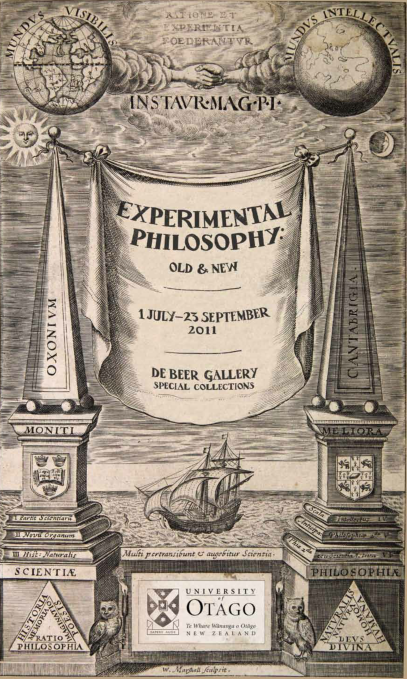

A couple of months ago, I requested your help: we needed an image for our exhibition poster. We received some excellent feedback – so thank you everyone! We eventually settled on a modified version of the frontispiece to 1640 translation of Bacon’s ‘De Augmentis Scientiarum’.

We hope you enjoy our exhibition!

* On Monday Peter Anstey will tell us all about this new discovery regarding Hume.

Experiment, Culture, and the History of Philosophy

One tremendous change over the past 27 years, which makes this redux not simply a repetition, has been the appearance, and reappearance, of experimental philosophy: that is, the emergence of experimental philosophy as a defining feature of the non-historical wing of the discipline, as well as a crucial focus of study (thanks in no small part to the work of the Otago group) for scholars studying the history of early modern philosophy.

A question of central methodological importance for the historian of philosophy concerns the appropriate relationship between the aspects of philosophy’s past that a scholar takes on, on the one hand, and on the other the current agenda of non-historical philosophy. Recently, in the results of a query launched by Mark Lance at the NewAPPS blog, my own deep worry about the state of the discipline was confirmed: a good many non-historian philosophers believe that, at the end of the day, history-of-philosophy scholarship should make itself relevant to the cluster of questions currently being investigated in philosophy. I could not disagree more strongly. To riff on John F. Kennedy’s famous line, I believe that we should not be asking what the history of philosophy can do for us, but rather what we can do for the history of philosophy. That is, we should be attempting to do justice to past thinkers by carefully reconstructing their own world of concerns. In doing so, we shall often have to move beyond the boundaries of what we consider philosophy (and even of what they considered philosophy).

I have argued in many fora that we should respect the historical usage of the term ‘philosophy’. Some have objected that it is a semantic issue –as in, a mere semantic issue– what might have been called by a certain name in another era. What is important, they say, is whether the activity so-called in fact has any continuity with what we are doing when we do philosophy. To some today, the discontinuity seems most evident when we consider early modern experimental philosophy. There simply is no meaningful sense, they maintain, in which we can think of meteorology as a proper part of philosophy, even if this is how it was conceived in the history of natural philosophy from Aristotle through (at least) Boyle.

We might suppose that this discontinuity is bridged to some extent by the recent appearance of an activity going by the name of ‘experimental philosophy’, but of course the scope of ‘experimental’ was very different for, e.g., Margaret Cavendish than for Joshua Knobe. Nonetheless, it is certainly worthwhile to reflect on what the 17th- and 21st-century versions of experimental philosophy share, and also on what they might someday share. For now, the new experimental philosophy sees itself as having common cause principally with experimental psychology. As some philosophers sympathetic to x-phi have argued, however, the concept of ‘experiment’ could be extended much further than has been done so far. Jesse Prinz, in particular, has suggested that ‘experiment’ could be understood broadly to include what we think of as ‘experience’: thereby reuniting it with its lexical ancestor, and also reconciling with the intuitions that x-phi initially came out against.

If experiment is (re-)broadened to include experience, then willy-nilly we arrive in a situation for philosophy in which, in effect, any source of information may be deemed of interest. Such a situation, I think, is one in which history-of-philosophy scholarship could thrive. It is one in which, moreover, this branch of scholarship would find common cause with historical anthropology. It might even open itself up to non-textual sources of information (e.g., instrument design, seed collections). The text would be dethroned as the exclusive source of information about what was motivating thinkers to come up with the ideas they had.

For a long time it has seemed unnecessary to historians of philosophy to move beyond texts, since philosophy is about ideas, and where else but in texts are ideas encoded? Certainly, texts are a useful source of ideas from the past, but seed collections and instrument design are also, so to speak, fossils of past intentions, and there is no reason why they should not complement texts of philosophy, just as the layout of graves complements hieroglyphic texts in an Egyptologist’s effort to reconstruct ancient Egyptian ideas about the afterlife.

But we tend to think of an Egyptologist’s work as having to do with culture, while we do not, today, think of historians of philosophy as specialists in culture at all. Historians of philosophy are supposed to be engaging with more-or-less timeless ideas, which are not supposed to be bound by the parameters of the culture inhabited by the thinker who had them. But let’s be serious. Is, say, Leibniz’s account of the fate of the soul of a dog after death (that is, shrinking down into a microscopic organic body and floating around in the air and in the scum of ponds for all eternity) really any more viable a candidate for the true theory of life after death than the account offered in The Egyptian Book of the Dead? I don’t believe so, and when I read Leibniz’s account it is not because I am considering adopting this account myself. It is because I am interested in the range of ways people in different times and places have conceptualized the irresolvable problem of the fate of the soul. I specialize in 17th-century Christian European approaches to this mystery, but I could just as easily have been an Egyptologist.

To acknowledge that we are studying culture –not all culture, but a particular manifestation of a certain culture: the European educated elite, which leaves its traces in texts, but not only in texts– is to make a move that is exactly parallel to the one practitioners of non-historical experimental philosophy are currently making relative to the discipline that houses them. Current x-phi is putting philosophy back into culture by empirically studying the culture-bound nature of intuitions, rather than resting content with the intuitions of self-appointed experts in intuition-having. This is a welcome development, but I believe it must be seen as just one small part of a broader project of re-embedding philosophy in culture, and I believe historians of philosophy have a particularly important role to play in this project. Philosophy in history is philosophy in culture.

Even if Boyle and Cavendish meant something different by ‘experimental philosophy’ than Knobe and Nichols do, to take an interest in Boyle and Cavendish’s conception of philosophy as extending to experimental science is to contribute in a specialized way, I believe, to the overall aim of current x-phi, which is to study how people in different times and places actually think. In pursuing this aim, current x-phi practitioners have found common cause with experimental psychologists. The parallel interdisciplinary move for the historian of philosophy should be one that brings us closer to the work of historical anthropologists.

Newton’s 4th Rule for Natural Philosophy

Kirsten Walsh writes…

In book three of the 3rd edition of Principia, Newton added a fourth rule for the study of natural philosophy:

- In experimental philosophy, propositions gathered from phenomena by induction should be considered either exactly or very nearly true notwithstanding any contrary hypotheses, until yet other phenomena make such propositions either more exact or liable to exceptions.

- This rule should be followed so that arguments based on induction be not be nullified by hypotheses.

Arguably this is the most important of Newton’s four rules, and it certainly sparked a lot of discussion at our departmental seminar last week. Let us see what insights we can glean from it.

Rule 4 breaks down neatly into three parts. I shall address each part in turn.

1. Propositions (acquired from the phenomena by induction) should be regarded as true or very nearly true.

While the term ‘phenomenon’ usually refers to a single occurrence or fact, Newton uses the term to refer to a generalisation from observed physical properties. For example, Phenomenon 1, Book 3:

- The circumjovial planets [or satellites of Jupiter], by radii drawn to the centre of Jupiter; describe areas proportional to the times, and their periodic times – the fixed stars being at rest – are as the 3/2 powers of their distances from that centre.

- This is established from astronomical observations…

Newton uses the term ‘proposition’ in a mathematical sense to mean a formal statement of a theorem or an operation to be completed. Thus, he further identifies propositions as either theorems or problems. Propositions are distinguished from axioms in that propositions are not self-evident. Rather, they are deduced from phenomena (with the help of definitions and axioms) and are demonstrated by experiment. For example, Proposition 1, Theorem 1, Book 3:

- The forces by which the circumjovial planets [or satellites of Jupiter] are continually drawn away from rectilinear motions and are maintained in their respective orbits are directed to the centre of Jupiter and are inversely as the squares of the distances of their places from that centre.

- The first part of the proposition is evident from phen. 1 and from prop. 2 or prop. 3 of book 1, and the second part from phen. 1 and from corol. 6 to prop. 4 of book 1.

Newton appears to be using ‘induction’ in a very loose sense to mean any kind of argument that goes beyond what is stated in the premises. As I noted above, his phenomena are generalisations from a limited number of observed cases, so his natural philosophical reasoning is inductive from the bottom up. Newton recognises that this necessary inductive step introduces the same uncertainty that accompanies any inductive generalisation: the possibility that there is a refuting instance that hasn’t been observed yet.

Despite this necessary uncertainty, in the absence of refuting instances, Newton tells us to regard these propositions as true or very nearly true. It is important to note that he is not telling us that these propositions are true, simply that we should act as though they are. Newton is simply saying that if our best theory fits the available data, then we should regard it as true until proven otherwise.

2. Hypotheses cannot refute or alter those propositions.

In a previous post I argued that, in his early optical papers, Newton was working with a clear distinction between theory and hypothesis. In Principia Newton is working with a similar distinction between propositions and hypotheses. Propositions make claims about observable, measurable physical properties, whereas hypotheses make claims about unobservable, unmeasurable causes or natures of things. Thus, propositions are on epistemically surer footing than hypotheses, because they are grounded on what we can directly experience. When faced with a disagreement between a hypothesis and a proposition, we should modify the hypothesis to fit the proposition, and not vice versa. Newton explains this idea in a letter to Cotes:

- But to admitt of such Hypotheses in opposition to rational Propositions founded upon Phaenomena by Induction is to destroy all arguments taken from Phaenomena by Induction & all Principles founded upon such arguments.

3. New phenomena may refute those propositions by contradicting them, or alter those propositions by making them more precise.

This final point highlights the a posteriori justification of Newton’s theories. In Principia, two methods of testing can be seen. The first involves straightforward prediction-testing. The second is a more sophisticated method, which involves accounting for discrepancies between ideal and actual motions by a series of steps that increase the complexity of the model.

In short, Rule 4 tells us to prioritise propositions over hypotheses, and experiment over speculation. These are familiar and enduring themes in Newton’s work, which reflect his commitment to experimental philosophy. Rule 4 echoes the remarks made by Newton in a letter to Oldenburg almost 54 years earlier, when he wrote:

- …I could wish all objections were suspended, taken from Hypotheses or any other Heads then these two; Of showing the insufficiency of experiments to determin these Queries or prove any other parts of my Theory, by assigning the flaws & defects in my Conclusions drawn from them; Or of producing other Experiments wch directly contradict me…

Leibniz: An Experimental Philosopher?

Alberto Vanzo writes…

In an essay that he published anonymously, Newton used the distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy to attack Leibniz. Newton wrote: “The Philosophy which Mr. Newton in his Principles and Optiques has pursued is Experimental.” Newton went on claiming that Leibniz, instead, “is taken up with Hypotheses, and propounds them, not to be examined by experiments, but to be believed without Examination.”

Leibniz did not accept being classed as a speculative armchair philosopher. He retorted: “I am strongly in favour of the experimental philosophy, but M. Newton is departing very far from it”.

In this post, I will discuss what Leibniz’s professed sympathy for experimental philosophy amounts to. Was Newton right in depicting him as a foe of experimental philosophy?

To answer this question, let us consider four typical features of early modern experimental philosophers:

- self-descriptions: experimental philosophers typically called themselves such. At the very least, they professed their sympathy towards experimental philosophy.

- friends and foes: experimental philosophers saw themselves as part of a tradition whose “patriarch” was Bacon and whose sworn enemy was Cartesian natural philosophy.

- method:experimental philosophers put forward a two-stage model of natural philosophical inquiry: first, collect data by means of experiments and observations; second, build theories on the basis of them. In general, experimental philosophers emphasized the a posteriori origins of our knowledge of nature and they were wary of a priori reasonings.

- rhetoric: in the jargon of experimental philosophers, the terms “experiments” and “observations” are good, “hypotheses” and “speculations” are bad. They were often described as fictions, romances, or castles in the air.

Did Leibniz have the four typical features of experimental philosophers?

First, he declared his sympathy for experimental philosophy in passage quoted at the beginning of this post.

Second, Leibniz had the same friends and foes of experimental philosophers. He praised Bacon for ably introducing “the art of experimenting”. Speaking of Robert Boyle’s air pump experiments, he called him “the highest of men”. He also criticized Descartes in the same terms as British philosophers:

- if Descartes had relied less on his imaginary hypotheses and had been more attached to experience, I believe that his physics would have been worth following […] (Letter to C. Philipp, 1679)

Third, the natural-philosophical method of the mature Leibniz displays many affinities with the method of experimental philosophers. To know nature, a “catalogue of experiments is to be compiled” [source]. We must write Baconian natural histories. Then we should “infer a maximum from experience before giving ourselves a freer way to hypotheses” (letter to P.A. Michelotti, 1715). This sounds like the two-stage method that experimental philosophers advocated: first, collect data; second, theorize on the basis of the data.

Fourth, Leibniz embraces the rhetoric of experimental philosophers, but only in part. He places great importance on experiments and observations. However, he does not criticize hypotheses, speculations, or demonstrative reasonings from first principles as such. This is because demonstrative, a priori reasonings play an important role in Leibniz’s natural philosophy.

Leibniz thinks that we can prove some general truths about the natural world a priori: for instance, the non-existence of atoms and the law of equality of cause and effect. More importantly, a priori reasonings are necessary to justify our inductive practices.

When experimental natural philosophers make inductions, they presuppose the truth of certain principles, like the principle of the uniformity of nature: “if the cause is the same or similar in all cases, the effect will be the same or similar in all”. Why should we take this and similar principles to be true? Leibniz notes:

- [I]f these helping propositions, too, were derived from induction, they would need new helping propositions, and so on to infinity, and moral certainty would never be attained. [source]

There is the danger of an infinite regress. Leibniz avoided it by claiming that the assumption of the uniformity of nature is warranted by a priori arguments. These prove that the world God created obeys to simple and uniform natural laws.

In conclusion, Leibniz really was, as he wrote, “strongly in favour of the experimental philosophy”. However, he aimed to combine it with a set of a priori, speculative reasonings. These enable us to prove some truths on the constitution of the natural world and justify our inductive practices. Leibniz’s reflections are best seen not as examples of experimental or speculative natural philosophy, but as eclectic attempts to combine the best features of both approaches. In his own words, Leibniz intended “to unite in a happy wedding theoreticians and observers so as to improve on incomplete and particular elements of knowledge” (Grundriss eines Bedenckens […], 1669-1670).

Experimenting with taste and the rules of art

Juan Gomez writes…

In 1958 Ralph Cohen published a paper titled David Hume’s Experimental Method and the Theory of Taste, where he argues that the main contribution of Hume’s essay Of the Standard of Taste (OST) was his “insistence on method, on the introduction of fact and experience to the problem of taste.” I agree with Cohen, but I think his overall interpretation of the essay on taste still falls short of giving a proper account of Hume’s theory of taste. I’d like to build on Cohen’s statement and support it with the help of the framework we are proposing in this project, where Early Modern Experimental Philosophy plays a prominent role.

Hume’s essay on taste begins with a description of the paradox of taste: It is obvious that taste varies among individuals, but it is also obvious that some judgments of taste are universally agreed upon (Hume’s example is that everyone admits that John Milton is a better writer than John Ogilby). Hume relies on the experimental method to solve the paradox. From the initial paragraphs of the essay we can see that Hume is calling for an approach to the appreciation of art works that resembles the experimental method of natural philosophy. If we are to solve the problem of taste, we need to focus on particular instances, and from them we can deduce the ‘rules of composition’ or ‘rules of art.’ This is achieved the same way natural philosophy observes the phenomena to deduce the laws of nature. The main reason for this focus on particular over the general is that Hume thinks that in matters of taste, as well as in morality founded on sentiment, “The difference among men is really greater than at first sight appear.” Although everyone approves of justice and prudence in general, when it comes to particular instances we find that “this seeming unanimity vanishes.”

The objects we appreciate as works of art, according to Hume, possess qualities that “are calculated to please, and others to displease.” The essay on taste applies the experimental method to particular experiences with artworks, and after a number of these experiences we can identify those qualities which comprise the rules of art:

- “It is evident, that none of the rules of composition are fixed by reasonings a priori, or can be esteemed abstract conclusions of the understanding, from comparing those habitudes and relations of ideas, which are eternal and immutable. Their foundation is the same with that of all the practical sciences, experience; nor are they anything but general observations, concerning what has been universally found to please in all countries and in all ages.” (OST, 210)

We need to approach matters of taste the same way we approach matters of natural philosophy: by focusing on the particular phenomena, which in this case are our interactions with works of art. Hume’s essay on taste works as a guide for the appreciation of art. It is not, as most of the scholars who comment on Hume’s essay believe, a method just for critics to apply, but rather a guide for any individual to engage in an aesthetic experience. Hume tells us that one of the aims of the essay is “to mingle some light of the understanding with the feelings of sentiment,” so the faulty of delicacy of taste takes a central role in Hume’s theory. Such faculty can and should be improved and developed, which leads us to think that the process Hume describes is not only for the critics but open to anyone.

- “But though there be naturally a very wide difference in point of delicacy between one person and another, nothing tends further to encrease and improve this talent,than practice in a particular art, and the frequent survey or contemplation of a particular species of beauty.” (OST, 220)

If we want to derive the most pleasure out of our aesthetic experiences we need to experiment with works of art in order to develop our delicacy of taste.

If we accept this reading of Hume’s essay we can shed light on its purpose. It was not the attempt to establish a standard of taste, but rather a guide for engaging with works of art and to have discussions regarding matters of taste.