Probable knowledge in Butler’s Analogy

Juan Gomez writes…

In my previous post I presented Bishop Halifax’s preface to Joseph Butler’s Analogy of Religion, Natural and Revealed. I focused on the discussion regarding the method applied by Butler both in the Analogy and in his Sermons which is described as an a posteriori method that deduces all knowledge from facts and observations. In this post I examine Butler’s own description of his method in the Analogy where he justifies the usefulness of probable knowledge.

Butler spends the entire introduction to the Analogy explaining and justifying his methodology. He begins by distinguishing probable from demonstrative evidence: the former “admits of degrees; and of all variety of them, from the highest moral certainty, to the very lowest presumption.” Probable knowledge arises from our observation of facts and generates conclusions that though imperfect and not certain are suitable for imperfect beings like us; “probability is the very guide of life.” As an example of the way probable knowledge is a matter of degree he refers to an example Locke gives in the Essay (IV. xv. 5): while someone from a warm climate will not believe that water can become hard, arguing by analogy from his previous observations of water always being liquid, an Englishman will, also from analogy: (a) suppose that there may be frost in England any given day next January, (b) find it probable that there will be frost at least one day of that month, and (c) have moral certainty that there will be frost some day during winter.

The last and higher degree of probable knowledge is the one Butler tries to obtain in the Analogy. He insists that even though it provides imperfect knowledge, when it comes to human actions it is the best guide we have. For example, if there are two ways for me to get home, one of which there are rumours that it is unsafe, the other is known for its safety, it would be foolish of me to take the unsafe road even though the probability of being harmed was low. After this confirmation of the usefulness of probable knowledge Butler further specifies that this is the way arguing by analogy works: we argue from known facts to the unknown; from what reason shows to what we may know through revelation:

- …if there be an analogy or likeness between that system of things and dispensation of Providence, which revelation informs us of, and that system of things and dispensation of Providence, which experience together with reason informs us of, i.e. the known course of nature; this is a presumption, that they have both the same author and cause; at least so far as to answer objections against the former’s being from God, drawn from any thing which is analogical or similar to what is in the latter, which is acknowledged to be from him; for an Author of nature is here supposed.

This is a nice summary of Butler’s purpose in the Analogy: he wants to show that natural and revealed religion coincide, and that arguing by analogy we can confirm the wisdom and perfection of God through both. Further, he believes that this method is just because it is based on facts and observation and not on hypotheses. Butler contrasts his method with the one followed by Descartes:

- Forming our notions of the world upon reasoning without foundation for the principles which we assume, whether from the attributes of God, or any thing else, is building a world upon hypothesis, like Descartes. Forming our notions upon principles which are certain, but applied to cases to which we have no ground to apply them, (like those who explain the structure of the human body, and the nature of diseases and medicine from mere mathematics without sufficient data,) is an error much akin to the former: since what is assumed in order to make the reasoning applicable, is hypothesis. But it must be allowed just, to join abstract reasoning with the observation of facts, and argue from such facts as are known, to others that are like them; from that part of the divine government over intelligent creatures which comes under our view, to the larger and more general government over them which is beyond it; and from what is present, to collect what is likely, credible, or not incredible, will be hereafter.

Notice that Butler is not trying to claim that his method will provide certainty, but rather that his conclusions will be more credible than those derived from mere hypotheses. One of the central issues in the Analogy is the nature and existence of a future state. Butler argues that from what we know of our present stage in life through the observation of nature it is not unlikely that there is a future state. This is an interesting feature of the application of the experimental method in religion. Facts and observations are still the only sources for acquiring knowledge, but instead of the certainty they provide in natural philosophy they give us, at best, highly probable knowledge about the government of God and the future life. Butler’s discussion in this introduction is of special interest for us since he explicitly rejects the use of hypotheses and mere speculation:

- As there are some, who, instead of thus attending to what is in fact the constitution of nature, form their notions of God’s government upon hypothesis: so there are others, who indulge themselves in vain and idle speculations, how the world might possibly have been framed otherwise than it is… Let us then, instead of that idle and not very innocent employment of forming imaginary models of a world, and schemes of governing it, turn our thoughts to what we experience to be the conduct of nature with respect to intelligent creatures; which may be resolved into general laws or rules of administration, in the same way as many of the laws of nature respecting inanimate matter may be collected from experiments.

We can see then that the rejection of hypotheses and mere speculation was also present in discussions about religion, even when those who sided with the experimental method like Butler and Turnbull admit that all we can conclude about the future state is, at best, highly probable and hence imperfect knowledge. This was not a problem from them, since they were still arguing from things we know, and since it is suitable to the nature of human beings that we only acquire probable knowledge of the future, more perfect state. However, this was not the only way figures sympathetic to the experimental method argued about the government of God. As we mentioned in the previous post Butler’s a posteriori method is contrasted with Samuel Clarke’s a priori method, but I leave this discussion for my next post.

Joseph Butler and Method in Moral Philosophy and Religion

Juan Gomez writes…

One of the features that we have explored in our project is the application of the experimental method in areas other than natural philosophy. I have focused on the work of George Turnbull to illustrate how the method was applied in moral philosophy and religion. In my next series of posts I want to focus on the work of Joseph Butler (who was arguably one of the figures that most influenced Turnbull) and explore his ideas on method in moral and religious inquiries.

As an introductory post to this series I will focus on the preface that appeared in the 1788 edition of Butler’s Analogy of Religion (first edition 1736) by Samuel Halifax, Bishop of Gloucester. In this preface Halifax gives an account of Butler’s ‘moral and religious systems’ that serves as a summary of Butler’s main ideas.

Halifax tells us that Butler’s moral system can be found mainly in the first three of his collection of Sermons, which are on human nature. Halifax highlights the way Butler proceeds to determine human nature:

What the inward frame and constitution of man is, is a question of fact; to be determined, as other facts are, from experience, from our internal feelings and external senses, and from the testimony of others…From contemplating the bodily senses, and the organs or instruments adapted to them, we learn that the eye was given to see with, the ear to hear with. In like manner, from considering our inward perceptions and the final causes of them, we collect that the feeling of shame, for instance, was given to prevent the doing of things shameful; compassion, to carry us to relieve others in distress; anger, to resist sudden violence offered to ourselves.

The method for acquiring knowledge of our moral system must be the same we employ to discover external facts. Halifax contrasts this method that Butler adhered himself to with the one used by Samuel Clarke. Halifax and Butler both see the two methods not as opposed to each other but rather as complementary:

The reader will observe, that this way of treating the subject of morals, by an appeal to facts, does not at all interfere with that other way, adopted by Dr. Samuel Clarke and others, which begins inquiring into the relations and fitness of things, but rather illustrates and confirms it.

It is interesting that Clarke is portrayed as following an a priori method in his moral inquiries, and I will leave the analysis of this and its relation to Butler’s method for a future post where we will examine the correspondence between Butler and Clarke regarding this issue. Since this is just an introductory post, I want to finish by showing Halifax’s rendering of Butler’s method in his religious work.

Butler’s main philosophical text was his Analogy, where he deals with natural and revealed religion and argues that the former is confirmed in the latter, both giving us evidence for the divine government of the world. The way Butler proceeds in this text is by arguing by analogy from the natural to the moral realm:

This way of arguing from what is acknowledged to what is disputed, from things known to other things that resemble them, from that part of the divine establishment which is exposed to our view to that more important one which lies beyond it, is all on hands confessed to be just. By this method Sir Isaac Newton has unfolded the system of nature; by the same method Bishop Butler has explained the system of grace; and thus, to use the words of a writer, whom I quote with pleasure, has ‘formed and concluded a happy alliance between faith and philosophy.’

One of the advantages of this method of analogy is that (as we will see in my next post where we examine Butler’s Analogy in a bit more detail) it does not lead to a claim of certain knowledge about the doctrines of religion, but it rather leads to a high degree of credibility in them. This feature allows Butler to get rid of a number of objections. Further, if the analogy Butler argues for is a strong one, then all objections made against revealed religion will also count as objections to natural religion, which is a consequence the objectors will not want to admit.

As we have seen in this brief account of Halifax’s preface, it appears that a striking feature of Butler’s work in morality and religion is the methodology he applies in both areas, one that argues from facts and experience instead of hypotheses and speculations:

Instead of indulging to idle speculations, how the world might possibly have been better than it is; or, forgetful of the difference between hypothesis and fact, attempting to explain the divine economy with respect to intelligent creatures, from preconceived notions of his own; he [Butler] first inquires what the constitution of nature, as made known to us in the way of experiment, actually is; and from this, now seen and acknowledged, he endeavours to form a judgment of that larger constitution, which religion discovers to us.

In my next post we will examine Butler’s application of this method in his Analogy and his defense of probable knowledge.

Feijoo and his ‘Magisterio de la experiencia’ (lessons of experience), Part III

Juan Gomez writes…

In my last two posts I commented on an essay by Benito Feijoo. First we examined how he pictures the history of philosophy as the contest between two ladies —Solidína (experience) and Idearia (imagination) — to conquer the world. He sides with experience, and we also examined some of the arguments he gives to support the adoption of the experimental method and the rejection of mere speculation. In today’s post I want to follow Feijoo further, examining in particular his thought that just as we must abandon speculation when it is unaided by experience, we must also be cautious and keep in mind that experience without reasoning can also lead us astray in our quest for knowledge.

After spending most of his essay showing (through examples) that the proper path to knowledge is to follow the experimental method, Feijoo concludes with 3 capital errors that frequently take place in our experimental observations:

- We shall conclude this discourse, by pointing out three capital errors, which stem from lack of reflection in experimental observations. The first is that of taking for the effect that which is cause, and for cause that which is effect. The second is to take for cause something that only happens accidentally and has no influence at all. The third is, between two effects of the same cause, to take one as the cause of the other. I shall show examples of these three errors in observations pertaining to Medicine.

Of the first type of mistake Feijoo gives us a case where someone drinks water excessively to quench an overwhelming thirst. A few hours later such person suffers a fever, and it is commonly thought that the cause of the fever is the excessive consumption of water. However this is a false conclusion due to the lack of reflection when observing. If we reason, we can see that the sickness is the cause of the thirst that leads to the excessive consumption of water.

Feijoo warns us that this kind of mistake is very dangerous in medicine, since the lack of reflection and reasoning leads the physician to err in his diagnosis and prevent him from curing the disease.

The second kind of mistake takes place when we assign as the cause something that only happens accidentally. Feijoo tells us that this mistake is committed frequently by ‘superstitious souls’ that constantly assign to their diseases causes that have nothing to do with it. The most common mistaken cause in these cases is the weather. Patients frequently blame their disease on the weather: If during summer the weather is hot, the disease is taken to be caused by the excessive heat, but if summer is not hot enough, then this is also taken to be the cause of the disease.

Finally, the third kind of mistake happens when between two effects of the same cause we take one to be the cause of the other. Feijoo’s example is that of a man that performs an intense physical exercise or activity, then drinks alcohol in excess, and later suffers a fever. While most men would take the excessive drinking to be the cause of the fever, the truth is that intense exercise is more likely to cause a fever than excessive drinking.

This account of capital errors in experimental observation concludes Feijoo’s essay. So what are we to make of his thoughts on the ‘Lessons of Experience’? Well I believe that in Feijoo we have a clear example of the dispersion of the experimental method across the Iberian Peninsula in the first half of the eighteenth century. Feijoo might be the most influential figure of this period in Spain, but he certainly was not alone in the adoption and promotion of the experimental method: Andres Piquer, Manuel Martinez, Juan de Cabriada, and the circles of doctors in Seville and Valencia all shared the beliefs Feijoo expresses in his text. As we have seen in Feijoo’s work, the novatores believed that the correct path towards knowledge was the one taken by Bacon, Boyle, and Newton.

Experience and Speculation in Geminiano Montanari

Alberto Vanzo writes…

Early modern experimental philosophy was not only a British phenomenon. On this blog, we have documented its influence in France, Germany, and Italy. Many studies on natural philosophy in early modern Italy seem in line with this suggestion. They portray the Florentine Accademia del Cimento as one of the first groups “to adopt an experimental method free of speculative theoretical arguments and contentions”. However, appearances can be deceiving. As Luciano Boschiero has argued, Italian natural philosophers in the Accademia del Cimento and elsewhere did not attempt to create a merely factual, “theory-free knowledge of nature”. They all endorsed theories and hypotheses which deeply shaped their experimental activity not unlike Boyle and Hooke, self-declared experimental philosophers who also developed speculative natural philosophies. Does this mean that Italian natural philosophers had a merely verbal allegiance to the experimental philosophy? Did they live a double life, designing and interpreting their experiments in the contest of natural-philosophical speculations and concerns, but then hiding them to portray their results as authoritative and trustworthy because based purely on matters of fact, independent from any theoretical assumptions?

To address these questions, it is useful to consider the case of Geminiano Montanari, one of the most prominent natural philosophers in late seventeenth-century Italy. It is easy to find the rhetoric of experimental philosophy in his works. He explicitly praises “experimental philosophy”, the academies that practice it, and especially experience, which “alone has the privilege of being teacher”. It is from experience that we must “derive” our natural-philosophical “maxims by anatomizing, so to say, the operations of nature”. Observations and experiments must be collected in a “universal and veridical history” of the world, which will be the basis for developing natural-philosophical theories. Does this mean that, for Montanari, we should rely only on empirical facts, reason inductively on their basis, and refrain from embracing hypotheses or making speculations?

Montanari’s extensive discussions of the existence of atoms and the void indicate otherwise. According to Montanari, those questions were not settled by the experimental or observational evidence which was available at the time. However, he did not claim that we should refrain from speculating on them until we have found enough empirical evidence. Montanari speculated on those questions, but he seems to place three limits on our speculation. First, he only speculated on on what we cannot experience. As long as we can, we must rely on experiments and observations as the basis for our natural-philosophical claims. Second, we should be aware that speculations are risky, uncertain, and difficult. Only experience can give us “light”. Montanari compares discussions on the vacuum to walking in the dark. Speculative reasonings can allow us to make some cautious steps into that obscure territory. Finally, there is a good way and bad way of speculating. The bad way is that of the Aristotelians, who hastily embraced natural-philosophical principles and made demonstrative reasonings on their basis. The good way is starting from what we know on the basis of experience and reasoning from it with the aid of the principles of mechanics and geometry (which Montanari takes to be innate). Proceeding in this way, we may be establish whether the invisible corpuscles that make visible bodies are ever at rest, or whether they move continuously, even though we lack empirical evidence of their movements.

In conclusion, Montanari’s approach to speculative reasoning seems to me to be compatible with his experimentalist stance. Montanari did not refrain from speculating and framing hypotheses, but in a cautious, controlled way, always granting pre-eminence to the deliverances of the senses. His pronouncements on the vacuum and on atoms were not a betrayal of experimental philosophy.

Feijoo and his ‘Magisterio de la experiencia’ (lessons of experience), Part II

In my previous post I introduced a text by the Spanish priest Beníto Jerónimo Feijoo. We saw Feijoo giving his picture of the history of philosophy by telling a story of two ladies, Solidína (experience) and Ideária (Imagination), who attempt to conquer the kingdom named Cosmósia (the world). Feijoo sides with Solidína (experience) and in the rest of the essay he gives an argument for the adoption and promotion of the experimental method and the rejection of speculation unaided by experience.

The first thing he points out is

- … the little or no progress, which natural reason, unaided by experience, has made in the examination of the affairs of nature in the course of so many ages…What utility has the labours of so many men of excellent ingenuity, as have cultivated philosophy in the reasonable and speculative way, produced to the world? What art, either liberal or mechanical, of the many that are necessary for the service of man, or the good of the public, do we owe to speculative invention; and I might even say, what small advancement in any such art, has been derived from it?

Feijoo focuses on natural philosophy and medicine to show the errors of the way of philosophizing the schoolmen adhere to and teach by in the universities in Early Modern Spain. I will only consider here one of the examples he gives regarding natural philosophy. Feijoo comments on the discovery of the ‘pointing of the magnetic needle to the pole.’ His intention is to show that experience always needs to accompany all our reasonings. He tells us that the discovery of this property of the magnetic needle was first discovered in the thirteenth century, but the traditional way of philosophizing has prevented us from understanding how this property works:

- This admirable property [the pointing of the magnetic needle to the pole], which was totally unknown to the antients, was discovered in the thirteenth century, and immediately applied to the improvement of navigation. Upon its first discovery, the philosophers, according to their wonted custom of pretending to discern the causes of things, imputed this effect, as derived from an occult sympathy with the pole, contained in the very essence, form, and substance of the loadstone; and as this is supposed to be invariable, they concluded, that the direction must infallibly be invariable also.

However, experience proved them wrong and with time navigators noticed that the direction does vary and not always points directly to the pole. The philosophers had to reluctantly accept this even though they tried to discredit the observations of reliable navigators. But this didn’t deter them from making further speculations. Once it was discovered that at some places there is no variation of the direction of the needle, ‘under the meridian of the Azores,’

- … astronomers and geographers thought they had found out a fixed station, whereat to commence the first meridian… But this idea soon vanished, for a little while afterwards, they discovered two other meridians, where there was no variation… Upon this, they thought they had found out a certain principle, whereon to ground a compleat system for calculating or computing variations, by graduating them for the intermediate stations, in proportion to their greater or less distance from the mean space between the two places where there was no variation.

But once again a new discovery through experience disproved their speculations

- … they discovered, that this declination of the magnetic needle, varied more or less at the same place at different times, and that this change of variation was perpetual… In this instance, may be seen the fallibility of the most plausible reasonings unaccompanied by experiments.

Feijoo’s comments are very interesting. Notice that he is not saying that speculations themselves are the source of error, but rather he points out that they most certainly lead to error when unaided by experience. In the compass case the rules were at one instance deduced from experience, but once the speculative philosophers left experience aside they fell into error. Feijoo clarifies this thought in the following passage

- If the rules deduced from experimental observations are so fallible, that it is absolutely necessary in order to avoid all error, to pursue the thread of them so scrupulously, that reason should not venture to advance a step, without the light of an experiment appropriated to the business it is in search of; I say, if these rules are not to be relied on, what confidence can we place in those maxims, which derive their origin from our arbitrary ideas?

Feijoo is being very cautious here; he admits that even rules deduced from experience might be falsified, so we need to constantly check them with experiments and observations. Feijoo clearly prefers the method of experience, but he is also aware that experience sometimes can lead us astray. In the compass example shown above Feijoo tells us that our reasoning always needs to be aided by experimental observation. Further in the essay, as we will examine in a future post, he tells us that our senses alone are not enough for the acquisition of true knowledge, which can only be reached through reasoning and experience used together.

Feijoo and his ‘Magisterio de la experiencia’ (lessons of experience)

Juan Gomez writes…

I have posted on this blog regarding early modern experimental philosophy in Spain (here and here). Contrary to the common opinion that Spain in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was a ‘backwards’ nation when compared to France and England, I have pointed out how many Spanish thinkers were aware of and advocated for the application of the ‘new’ science. In today’s post I want to focus on a text by the thinker who is arguably one of the most influential figures in Spanish thought, Benito Jerónimo Feijoo.

Feijoo was born in 1676 and ordained under the order of Saint Benedict in 1690 after studying in the monastery of San Vicente de Salamanca. He moved to Oviedo in 1709 where he taught and developed his philosophical work. The most influential of his texts was the Teatro Crítico Universal, a nine volume work published between 1726 and 1740. Each of the volumes contains a number of essays on a variety of topics including natural philosophy, history, medicine, women, education, transubstantiation, and religion. I want to focus on a discourse from the fifth volume (1733) titled ‘El gran magisterio de la experiencia’ (The great lessons of experience).

The piece is an essay on the danger of pure speculation (‘reason unaided by experience’) and calls for the emphasis on experience and observation in all our inquiries. Feijoo begins by recounting a fable that was read to him from a French book by a foreign traveller. The story begins with the arrival of two ladies, Solidína and Ideária, in the Kingdom of Cosmósia with the intention of taking dominion over the Kingdom. Solidína was ´wise but simple,’ and her strategy for conquering the empire was the following:

- She went from house to house, making herself acquainted with everyone, teaching with clear and common voices true and useful doctrines… since everywhere she found sensible objects that examined through the ministry of the sense became the books for her lessons. Far from inspiring an indiscreet presumption among her disciples, she told them with humbleness that what she could teach was very little compared to the infinite amount there is to learn, and that to achieve even just an average knowledge of things immense work and discipline was necessary.

Ideária on the other hand was ‘ignorant but charlatan’ and had a very different strategy:

- She tried to establish an absolute despotism over her disciples, expediting an edict so that no one would believe what their eyes saw or what their hands felt… their disciples started to believe many maxims that used to be seen as impediments to knowledge: that truth can only be known through fiction; that there is a way of knowing things that a boy can learn in four days; that there is one man, that is all man (the same goes for all species), so that if one is known, all are known; that non-sensitive and inanimate things have their appetites, ears, and loves no less than sensitive and animate things… that all living beings are composed by a considerable degree of fire, not even excluding fishes, even though they are always under water.

Ideária ruled for a long time until there was a schism among her disciples. A subject named Papyráceo separated himself and introduced new dogmas:

- That all living beings (except men) are nothing but corpses; that even in man only a small part of the body entertains the presence of the soul; that the world is infinitely extended; that the movement of sub-lunar and celestial bodies is perennial; that imaginary space is a true and real body… that in all things imagination must be believed, and never the senses; and the latter deceive in all their representations; that the swan is not white, nor the crow black, nor fire hot, nor snow cold &c.

But fortunately the story does not end with Ideária’s rule. People found out that the maxims both her and Papyráceo defended were at most probable, so they remembered Solidína and brought her back to the city:

- They established her as the magnificent of the teaching rooms, where she teaches with more and more credit each day, contributing immensely to the favour of some great heroes, especially the two princes, Galindo and Anglosio, who are very fond of Solidína.

Feijoo goes on to explain the themes and characters the story alludes to, which are not that difficult to discern. Cosmósia is the world, coming from the Greek cosmos. Solidína is experience, since it ‘explains solidly its maxims with sensible demonstrations.’ Ideária is imagination, since it ‘founds its opinions on the vain representation of its ideas.’ The triumph of this kind of philosophy is represented by Pythagoras, Plato and Aristotle, out of whom came an ‘ideal physics instead of a solid and experimental one.’ The character of Papyráceo alludes to Descartes, since the former comes from the Latin word Papyrus, which is equivalent to the French ‘Carte’. Finally,

- experimental observation, which was only used before by the farmers for the cultivation of the crops, the due care of the fields and the propagation of livestock, was recently brought back pompously by some institutions set up to examine nature in this way. Among them, the most famous being the Royal Academy of the Sciences in Paris and the Royal Society of London chartered under the Monarchs of France and England, respectively, which are alluded by the princes Galindo and Anglosio, derived from the Latin terms for those nations, Gallia and Anglia.

It is clear from this introduction to Feijoo’s essay that he is promoting this picture of the history of philosophy as a very long and detrimental period where the way of doing philosophy without consideration for experiment and observation was superseded by the new method in the seventeenth century, as it is exemplified by the Royal institutions of France and England. And this just sets the scene for the rest of what Feijoo wants to say. In my next post I will explore Feijoo’s more detailed objections to the use of pure speculation and his call for experimental observation as the foundation of all knowledge.

Looking back: PATS workshop on Interdisciplinarity

Juan Gomez writes…

A few weeks ago the Early Modern Thought Research Theme here at Otago hosted a colloquium on “Practical Knowledges and Skill in Early Modern England.” After two days of great talks postgraduate students were able to take part in an ANZAMEMS sponsored workshop on “Interdisciplinarity in Medieval and Early Modern Research.” I took part in the workshop and in today’s post I want to share my thoughts on what turned out to be an outstanding event.

The main purpose of the workshop was to give postgraduate students tools to enhance current and future research projects. With this in mind the speakers shared how they had each in their own way been engaged with this interdisciplinary aspect of the Early Modern period. The talks were followed by practical sessions where we had the opportunity to think about and develop our research projects from an interdisciplinary perspective. The whole workshop was a huge success and I am sure I am not the only one that now has a better idea of how beneficial it is for research in the early modern period to look at/borrow from/collaborate with other disciplines.

Of special interest to me were the talks given by Peter Harrison on “Disciplinary boundaries in intellectual history: science, religion & philosophy” and Andrew Bradstock on “Religious language in early modern texts.” Harrison’s talk was a very clear and nice example of the interdisciplinary nature of the Early Modern period. It highlighted how the three disciplines that to our modern eyes seem very distinct drew on each other constantly. As readers of this blog know, I have done some research on George Turnbull’s work on Jesus Christ and miracles that exemplify this interaction between science, religion, and philosophy in the eighteenth century.

Andrew Bradstock’s talk made me think about how my research on Turnbull can me tremendously enhanced by drawing on the purely religious context of the time. For example,Turnbull’s Principles of Christian Philosophy draws heavily on passages from the bible, some of them that I am not that familiar with or might not know it’s significance at the time. By working with someone working on the history of religion or acquiring knowledge of it I can add another layer to my research that will enrich our understanding of Turnbull’s thought.

The workshop made it clear that crossing the boundaries of a particular discipline is not only fruitful but even necessary when engaged in early modern research. Given that there is a natural characteristic of interdisciplinarity to the early modern period we must leave the comfort zone of our own discipline if we want to carry out our research projects properly. Most of us have actually done this without noticing that we are engaged in interdisciplinary research. The workshop brought this to my attention and I started thinking about the many ways in which my research would have been improved if I had consciously made an effort to enrich my understanding of any given topic by allowing myself to explore what other disciplines have to offer. And this enrichment of knowledge works both ways; there are projects stationed in other disciplines that would be enhanced by what I have to offer as a researcher from a specific discipline, with a specific skill set.

This is not to say that early modern research cannot be carried out other than in an interdisciplinary manner, but rather that through interdisciplinarity we can enhance tremendously the research projects we are all developing from our specific discipline. Borrowing a phrase by Michael Cop at the Early Modern at Otago blog, the workshop showed that through interdisciplinarity “the future of early modern and medieval research looks promising indeed.”

Tracking Terms in the Encyclopædia Britannica: Part II

Juan Gomez writes…

In my previous post I explored the use of the terms ‘experimental philosophy’ and ’empiricism’ in the Encyclopædia Britannica. Today I will look at the terms ‘speculative’ and ‘rationalism’ throughout the first nine editions of the Encyclopædia.

Speculative

There is no entry for ‘speculative philosophy’ in any of the eighteenth and nineteenth century editions. However,the term ‘speculative’ on its own appears in the first seven editions (1771-1827). It is a very short entry, it was never expanded or modified and it disappears entirely from the 1853 edition onwards.

We can see Bacon’s contrast between speculative and practical present in this definition which remained in the exact same form in all the editions it appeared. It seems to be more of a dictionary definition pertaining to the standard meaning of the word at the time. This is also the case for the term ‘rational’ that appears only in the first edition (1771) of the Encyclopædia.

Rational/Rationalism

Although there was no entry for ‘rationalism’ until the 1853(8th) edition, we do find a brief entry for ‘rational’ in the first edition:

This is the only entry for ‘rational’ in any edition of the Encyclopædia. We can see that it does not have any connotation other than its specific use in mathematics and its use as an adjective meaning ‘reasonable.’

On the other hand, ‘rationalism’ appears for the first time in the same edition where the terms ’empiric’ and ‘experimental philosophy’ disappear, and there is no entry for ’empiricism’ yet (it first appeared in the 11th edition in 1910). We can see here that even by the mid-nineteenth century the term still had a restricted meaning that pertained specifically to religion.

As it was the case with ’empiricism,’ ‘rationalism’ only appears in its modern sense in the twentieth century, where two definitions if the term are given: one referring to it’s use regarding religion present in the quote above, and the second one regarding its use in philosophy:

It is not until the first decades of the twentieth century that we see the terms ‘rationalism’ and ’empiricism’ being used to refer to early modern philosophy, showing that the ESD framework has some considerable advantages over the RED for interpreting the Early Modern period.

Tracking Terms in the Encyclopædia Britannica

Juan Gomez writes…

Some time ago I wrote a post regarding David Fordyce’s Elements. This text was used almost in its entirety as the entry for moral philosophy in the Encyclopædia Britannica from the first edition in 1771 and until the seventh edition where it was modified and the replaced by an essay on the topic by William Alexander. I want to refer to the Encyclopædia again, this time to trace the description of four terms, namely ‘empiric,’ ‘experimental philosophy,’ ‘rational’ and ‘rationalism,’ and ‘speculative.’ I will focus on the first two terms in today’s post.

Empiric

The word ‘empiric’ appears in the first eight editions (1771 to 1898 when the ninth edition appeared). It is a very short entry and it restricts its use to method in medicine:

It is clear from the definition that the word had a different use than the one implied by the modern term ‘empiricism,’ which appeared for the first time in the eleventh edition(1910) of the Encyclopædia. In such editions the writer of the entry tells us that the term refers “in philosophy, [to] the theory that all knowledge is derived from sense-given data. It is opposed to all forms of intuitionalism, and holds that the mind is originally an absolute blank.” The last paragraph of the entry refers to the restricted definition of the term ‘empiric’ given in previous editions that I quoted above.

Experimental Philosophy

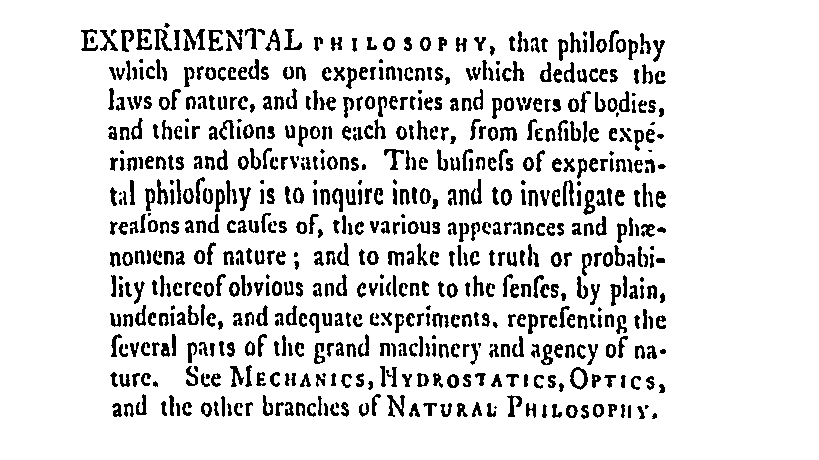

This term can be found in the first eight editions as well and disappears from the ninth edition onwards. The following is the definition from the first edition of the Encyclopædia:

However, the definition for Experimental Philosophy was substantially expanded for editions two to six, and then reduced to one small paragraph in the eighth edition. From 1778 (second edition) to 1823 (sixth edition) the entry consists in a general description and refers to seventeen items that form “the foundations of the present system of experimental philosophy.” The items are basic definitions of the object of study of experimental philosophy: natural bodies and their properties, extension, arrangement of particles, law of gravity, properties of light, and so on. For the seventh edition the entry was reduced to this:

The entry is the same for the eighth edition but from the ninth edition onwards there is no entry for ‘experimental philosophy.’

As far as the Encyclopædia Britannica is concerned, we can see that the terms used in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are better explained by using the ESD framework instead of the RED. The contrast between the meaning of the term ’empiric’ in the medical context and the later twentieth century entry on ’empiricism’ illustrates this nicely. As we will see in my next post, the way the terms ‘speculative’ and ‘rational’ were used gives us more evidence to prefer the ESD framework for interpreting the early modern period.

Experimental Philosophy in Spain Part II

Juan Gomez writes…

In my previous post I reviewed some texts from Spanish authors in the 17th century to show that, contrary to common opinion, intellectuals in the Iberian Peninsula were in fact acquainted with the progress and achievements of the new experimental philosophy. They did not just know of it, but actually advocated its application and called for the rejection of the old method of the scholastics. In this post I will conclude this overview of the ESD in Spain by looking at the work of the Novatores in the eighteenth century.

The texts we examined in my last post were both written by physicians. In the eighteenth century medicine remained as the forum for the promotion of experimental philosophy. The first author I will examine is Doctor Martín Martínez. He was a physician and professor of anatomy in Madrid, and royal physican to Phillip V. Besides a number of medical writings, in 1730 he published Filosofía Escéptica which consisted in a dialogue between an Aristotlian, a Cartesian, a Gassendist, and a Sceptic. In the preliminaries to this book he tells us that

- The spirit of this book is to give to the Curious Romantics an idea of the most famous philosophies that today run through Europe, relegating that Aristotle just for theological studies.

Even in the 1730’s books in Spain still included a statement of approval made by a priest or friar that confirmed that there was nothing in the book to be censured. The censorship for Filosofía Escéptica was written by Friar Agustín Sanchez and in it we find a statement in the spirit of experimental philosophy. Speaking of the account Martínez gives of the Aristotelian, Cartesian, and Gassendist positions he tells us that the Doctor

- Is determined not to follow any of them, but is inclined towards what he judges more plausible; he does not believe in what experience cannot confirm, based on the fact that words cannot reach the truth of physical and material things, nor their natures and properties; what experience cannot testify, and persuade, cannot be known by words.

Martínez begins his dialogue by giving a brief history of philosophy in Spain, blaming the Arabians for the introduction of Aristotelian philosophy,

- From which that contentious and vociferous philosophy we call Scholastic, as opposed to Experimental, has been derived.

A few lines later Martínez comments that he shares the same opinion held by Bacon:

- The most judicious Verulam also held, that of all the philosophies that have been invented, and received, so many were but fables, and Comical Scenes, each of them making the world to their liking, amassing the Elements to the measure of their palate, and arbitrarily establishing hypotheses as difficult to believe, as they are to prove.

In the case of Martín Martínez we can see the experimental philosophy and the rejection of mere speculation clearly represented. But to show that this was not an isolated case I turn now to another doctor, Andrés Piquer. Out of all the Novatores that practices medicine, Piquer was the one that published most on other topics. He published a book on logic, one on moral philosophy, and one on physics. This last one was published in 1745 under the title Física Moderna Racional, y Experimental (Modern Physics, Rational and Experimental). Piquer begins this book by giving some preliminaries about the state and history of physics and the method to follow. In his historical account he tells us that

- Physics was wrongly cultivated for many centuries, until Francis Bacon Lord Verulam, Great Chancellor of England, towards the end of the sixteenth century, started to renew it, freeing it form the superfluity of reasoning, and manifesting, that the true way to advance in it is through the path of experience.

Speaking about the proper method Piquer sets up a distinction that illustrates the presence of the ESD (in some form) in Spain:

- Modern physicists, are either Systematic, or Experimental. The former explain nature according to some system; the latter discover it through the way of experience. The Systematic form in the imagination some idea, or drawing of the principal parts of the World, of its connections, and mutual correspondence; and holding such idea, that sometimes is strictly willed, as a principle, and foundation of their Philosophy, try to explain everything that occurs in the universe according to it. This has been done by Descartes, and Newton. The Experimental work to collect many experiments, combine them, and use them as the basis of their reasonings. This is how Robert Boyle, Boerhaave, and many other philosophers of these times treat physics.

One of the interesting features of this passage is that Piquer groups Descartes and Newton together under systematic philosophers! However, I don’t have the space or time to discuss this very interesting issue in this post, but Piquer’s distinction between systematic and experimental is something worth looking into. For now, I believe I have provided some very interesting passages from early modern Spanish authors that show that they were acquainted with experimental philosophy and opposed and rejected mere speculation.

N.B. The English translation of the quotes presented here is mine