Symposium on Experimental Philosophy and the Origins of Empiricism

St Margaret’s College, University of Otago, 18-19 April 2011

Monday 18 April

9.00 Introductory Session (Peter Anstey and Alberto Vanzo)

9.30 Discussion of Peter Anstey, The Origins of the Experimental/Speculative Distinction

Discussant: Gideon Manning

Chair: Alberto Vanzo

11:30 Discussion of Juan Gomez, The Experimental Method and Moral Philosophy in the Scottish Enlightenment

Discussant: Charles Pigden

Chair: Kirsten Walsh

14:30 Discussion of Kirsten Walsh, De Gravitatione and Newton’s Mathematical Method

Discussant: Keith Hutchison

Chair: Philip Catton

20:00 European Panel of Experts (video conference)

Chair: Peter Anstey

Tuesday 19 April

9:30 Discussion of Peter Anstey, Jean Le Rond d’Alembert and the Experimental Philosophy

Discussant: Anik Waldow

Chair: Juan Gomez

11:30 Discussion of Alberto Vanzo, Empiricism vs Rationalism: Kant, Reinhold, and Tennemann

Discussant: Tim Mehigan

Chair: Philip Catton

14:30 Discussion of Alberto Vanzo, Experimental Philosophy in Eighteenth Century Germany

Discussant: Eric Watkins

Chair: Peter Anstey

16:30 Final plenary session, led by Gideon Manning

17:00 Conclusion

Attendance at the symposium is free. However, space is limited, so we advise you to register early. To register and for information, please email peter.anstey@otago.ac.nz.

Abstracts of all papers are available here. If you cannot attend, but would like to read some of the papers, send us an email.

Experimental and Speculative Philosophy in Kant’s Age

Alberto Vanzo writes…

We saw in earlier posts that experimental-speculative distinction was widely present within early modern philosophy, including eighteenth century Germany. The distinction was clearly drawn in Tetens’ essay from 1775, six years before Kant published the first Critique. With that work, another distinction entered the scene. It was the distinction between empiricism and rationalism. The rationalism-empiricism distinction, developed and popularized in widespread works by Reinhold, Tennemann, and later Kuno Fischer, would eventually become the standard way of classifying early modern philosophers. The experimental-speculative distinction would fall into the almost total oblivion in which it lies today.

How did this process take place? It would be surprising if, with the publication of Kant’s first Critique in 1781, philosophers suddenly dropped the distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy altogether.

In fact, the lively debates surrounding the emergence of Critical philosophy in the late 1780s and 1790s were still framed, at least at times, in terms of the speculative-experimental distinction. In this post, I will present some evidence for this claim.

J.G.H. Feder published one of the first attacks on the first Critique in 1787, claiming that it was full “of the most abstract speculations of logic and metaphysics” (italics, here and below, are mostly mine). In Feder’s view, Kant was “too much a friend of the most abstract and profound speculations in Scholastic form”. One year earlier, Christoph Meiners criticized Kant’s “transcendentish [sic] speculations”, “independent from any experience” in the preface to a successful book.

Why did Feder and Meiners attack Kant? Because, in Feder’s words, Kant humiliated

- empirical philosophy, that is, the philosophy which is based only on observations and on the agreement of all of most human experiences, and on inferences based on the analogy between them, and fully renounces [to employ] demonstration[s] based on concepts in the study of nature […]

In other words, the philosophy that Kant allegedly humiliated was the same experimental (or as the Germans preferred to call it, observational) philosophy that Tetens had described in his essay of 1775. Feder and Meiners defended observational philosophy. By associating Kant’s name with speculation, they were categorizing Kant as an example of a speculative philosopher.

Kant’s followers accepted the classification of their philosophy as speculative. Replying to Feder in 1789, the Kantian J.C.G. Schaumann had no hesitation in calling Kant’s disciples “friends of speculation and critique”. In the same year, Reinhold opened his New Theory of the Human Capacity for Representation by claiming, against observational philosophers: “neither common understanding [scil. common sense], nor healthy understanding, but only reason guided by principles and trained through speculation could succeed in the study of experience”.

These quotes show that the experimental-speculative distinction was very much alive in Germany during the first reception of Kant’s Critical philosophy. The experimental-speculative distinction contributed to the self-understanding of the parties involved in the dispute.

The dichotomy of experiment and speculation was not the only way of categorizing the debates between Kant and experimental philosophers. A gifted Kant scholar, C.C.E. Schmid, published in 1788 “Some Remarks on Empiricism and Purism in Philosophy” to defend Kant from the criticisms of an experimental philosopher, C.G. Selle. The debate continued, with the term “empiricism” being often used to designate Kant’s opponents. The term that Schmid used to refer to Kant’s philosophy was the rather unusual term “purism”. Kant, instead, was classifying his philosophy as a form of rationalism in those very years. Clearly, the terminology was still rather fluid.

We all know who won the confrontation between anti-Kantian experimental philosophy on the one hand, Kantian and post-Kantian speculation on the other. The terms “speculation” and “speculative” soon acquired a new range of connotations in the philosophies of Schelling and Hegel. Observative or experimental philosophy lost popularity and its name was replaced by “empiricism”. Christian Garve was referring to the early stages of this process, when he wrote in 1796:

- it seems that in our time observation, which was formerly regarded as one of the first accomplishments of the philosophical spirit and the foundation of our scientific cognitions, since its object has been designated with the name of empirical, has fallen in discredit with some people.

Garve’s adjective “empirical” refers to the new term “empiricism”. “With some people” is clearly an understatement, reflecting Garve’s preference for the observational approach over Kantianism. While the historical notion of experimental or observational philosophy was falling into discredit, the historiographical dichotomy of empiricism and rationalism was on the rise. I will discuss this process in one of the next posts.

Next Monday, we’ll go back to Newton with a new post by Kirsten. Stay tuned!

Turnbull’s Treatise on Ancient Painting and the Experimental/Speculative Distinction

Juan Gomez writes…

In my previous post on David Fordyce’s thoughts on education, I showed how his speech to students on the commencement of the studies embodies the commitment to the method of the experimental philosophy. This is hardly surprising given that his teacher at Marischal, George Turnbull, expressed the same commitment a year before Fordyce’s speech in his Observations upon Liberal Education (1742). In this post I want to focus on an earlier text, his Treatise on Ancient Painting (1740). In addition to trying to find out “wherein the Excellence of Painting consists,” he wants to show the usefulness of this art and its essential role in education.

Relying heavily on texts by ancient authors, Turnbull claims that painting, and the arts in general, have always been (and should always be) connected to the study of nature. In this sense, pictures or paintings, when they reflect and are created in accordance to the laws of nature, can serve as proper samples for the study of nature. By analogy, moral paintings (which showcase the true excellence of art: Virtue) work as proper samples and ‘experiments’ for the study of human nature. (But the topic of ‘experiments’ in moral philosophy will have to wait a couple of posts, since I’m focusing strictly on the education issue first.)

The ESP distinction can be seen at work in the passages where Turnbull commends the experimental method and rejects speculation. Like he did in his Principles of Moral Philosophy, Turnbull expresses antipathy towards hypotheses and praises an emphasis on experiments and observation as the only true method for acquiring knowledge. When discussing one of the main purposes of travelling (since the Treatise on Ancient Painting was supposed to serve as a guide for young British travelers) he tells us the following:

- The Ancients travelled to see different Countries, and to have thereby Opportunities of making solid Reflexions upon various Governments, Laws, Customs and Policies, and their Effects and Consequences with regard to the Happiness or misery of States, in order to import with them into their own Country, Knowledge founded on Fact and Observation, from which, as from a Treasure of Things new and old, sure and solid Rules and Maxims might be brought forth for their Country’s Benefit on every Emergency. For this is certain, that the real Knowledge of Mankind can no more be acquired by abstract Speculation without studying human Nature itself in its many various Forms and Appearances, than the real Knowledge of the material World by framing imaginary Hypotheses and Theories, without looking into nature itself: And no less variety of Observations is necessary to infer or establish general Rules and Maxims in the one than in the other Philosophy. (Emphasis added)

In the final chapters of the book Turnbull again reminds us about the ‘true philosophy,’ this time leaning on Socrates, Bacon, and Newton for support. Arguing for the unity of natural and moral philosophy in education, Turnbull discusses the pleasure derived from the study of nature:

- Socrates long ago found fault with those pretended Enquirers into Nature, who amused themselves with unmeaning Words, and thought they were more knowing in Nature, because they could give high sounding Names to its various Effects; and did not inquire after the wise and good general Laws of Nature, and the excellent Purposes to which these steadily and unerringly work. My Lord Verulam tells us, that true Philosophy consists in gathering the Knowledge of Nature’s Laws from Experience and Observation. And Sir Isaac Newton hath indeed carried that true Science of Nature to a great height of Perfection… I shall only observe farther on this Head, that if this be the right method of improving and pursuing natural Philosophy, it must necessarily follow, that the Knowledge of the moral World ought likewise to be cultivated in the same manner, and can only be attain’d to by the like Method of enquiry: By investigating the general Laws to which, if there is any order in the moral World, or if it can be the Object of Knowledge, its Effects and Appearances must in like manner be reducible, as those in the corporeal World to theirs […]

As we can see, the works of George Turnbull and David Fordyce show evidence of the use of the ESP distinction in fields outside of natural philosophy. Beyond this, they show that the moral philosophy taught by these gentlemen in Aberdeen in the first half of the eighteenth century was driven by the characteristic attitude of the experimental method, shedding light on the development and roots of the ‘science of man’ in the eighteenth century.

Speculative and Experimental Philosophy in Universities: (Post-)Cartesianism

This is the second post in Dr Gerhard Wiesenfeldt‘s series on speculative and experimental philosophy in early modern universities.

Gerhard Wiesenfeldt writes…

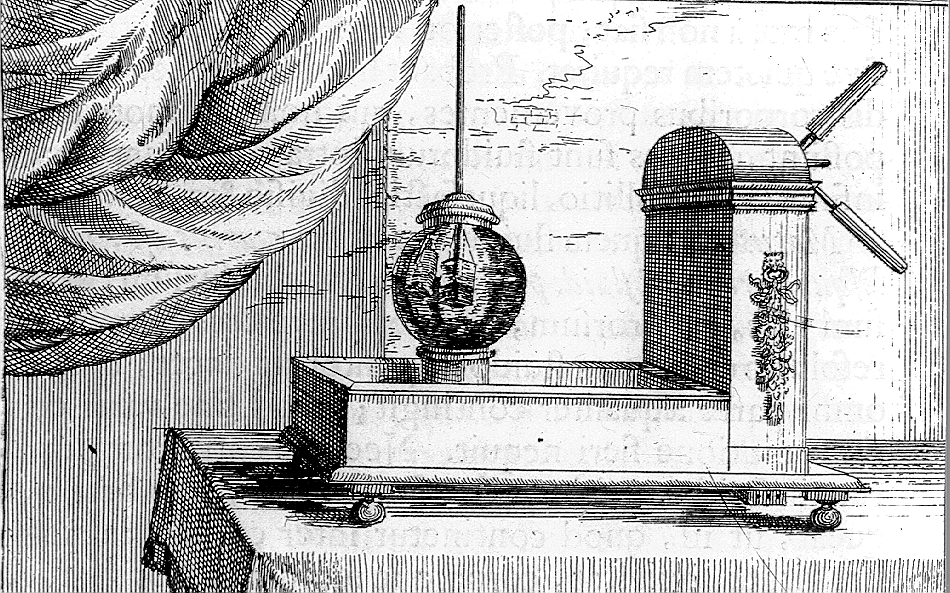

In my last post, I wrote about Johann Christoph Sturm’s experimental philosophy and his eclectic approach to speculative philosophy. A very different route to natural philosophy was taken by his colleague and friend, Burchard de Volder. De Volder was professor of philosophy at Leiden University and in 1675 became the first university lecturer to be officially charged with teaching ‘physica experimentalis’. While hardly known today, he was considered an important natural philosopher during his lifetime, he also was a correspondent of Newton, Leibniz and Huygens (who considered him to be the only other Dutchman to have understood Newton’s Principia). When he started teaching at Leiden, he was a clear-cut Cartesian with little inclination for experimental philosophy. He took up experimental philosophy only after the controversies on Cartesian philosophy at Leiden had reached such a level that the university (and in particular the faculty of philosophy) was seriously disrupted in its working. His decision to introduce experimental philosophy was probably motivated both by political considerations (the Cartesians at the university were under serious pressure and de Volder had reasons to fear being expelled) and by the urge to find ways of teaching philosophy that would not lead to conflict and even physical violence. In this he was supported by his conservative anti-Cartesian colleague Wolferd Senguerd, who started teaching experimental philosophy shortly after de Volder had began his lectures.

De Volder's airpump as illustrated by his colleague Wolferd Senguerd

While de Volder’s experimental lectures were largely based on Boyle’s New Experiments Physico-Mechanicall with some mathematical splashes from Stevin, he continued to teach speculative philosophy based solely on Descartes’ Principles of Philosophy. De Volder explicitly rejected Sturm’s eclectic approach and argued that speculative philosophy needed to be based on certain, universal principles, such as the Cartesian principle of clear and distinct ideas, in order to create a comprehensive philosophical system. Experimental and speculative philosophy had thus different foundations and remained largely unrelated. Occasionally, there were even contradictions between the two, when De Volder pointed out errors in Cartesian philosophy in his experimental lectures. Still, he maintained that natural philosophy needed to be developed in a systematic way, and that the Cartesian system was the best available.

Yet, over time, his judgment on this matter changed. In the 1690s he argued that Cartesian methodology worked only in the res cogitans, i.e. in mathematics and metaphysics, but not in natural philosophy, as there was no way to establish clear and distinct ideas on the physical world with certainty. While de Volder rejected Cartesian natural philosophy, he did not take up any of the other systems. He remained reluctant about Newton’s Principia and was not persuaded by Leibniz’s attempts to win him over. Instead, he ended up with a methodology not too far from Sturm’s, in stating that one needed to divide the physical world into parts on which certain hypotheses could be developed. He did not elaborate whether this still left room for speculative natural philosophy, but it is hard to see how such a science could have been maintained under these principles.

One of the contentions of these entries on university philosophy relates to the debate in this blog on the experimental/speculative versus rationalist/empiricist distinction. In terms of early 18th century university philosophy these distinctions are on an essentially different level. The distinction between rationalism and empiricism pertains to understanding philosophy as being divided into different schools (or sects). While one might describe rationalism and empiricism as the two biggest philosophical schools (or groups of schools), they were by no means the only ones – one philosopher at Helmstedt University counted no less than 26 different philosophical schools in 1735. The distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy, however, referred to different manners to practise philosophy independent of a particular school. Sturm and de Volder practised both experimental and speculative philosophy, but maintained that they were different enterprises, as did their students Wolff, ’s Gravesande and van Musschenbroek later on. At the same time experimental philosophy transcended philosophical schools, practised by Cartesians, Newtonians, Aristotelians, and Wolffians alike.

Speculative and Experimental Philosophy in Universities: Eclecticism

This is the first of two guest posts by Dr Gerhard Wiesenfeldt on speculative and experimental philosophy in late 17th century universities. Gerhard has published on early modern Dutch science, the visual culture of experiments, science in popular movies, biographies of ‘fameless’ scientists and romantic self-experiments. He is currently working on the different local cultures of science in the 17th and 18th centuries and their mutual interactions.

Gerhard Wiesenfeldt writes…

In late 17th century universities, experimental philosophy played a significant role, yet in a different manner to the role it played in the Royal Society. One of the traditional roles of universities had been to evaluate new knowledge and new knowledge systems and relate them to the existing sciences. In this context, the relation between experimental and traditional natural philosophy had to be addressed. Here, I want to discuss one of the various ways in which this relation was maintained, a way that became influential for the development of experimental philosophy in German speaking countries.

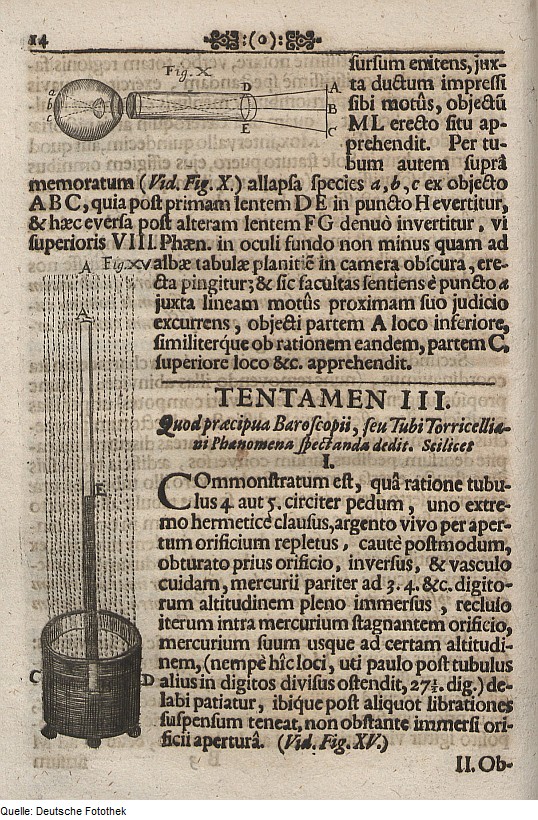

Johann Christoph Sturm, professor of mathematics and philosophy at the University of Altdorf in central Germany, was probably the leading university-based German natural philosopher of the late 17th century: he wrote the most widely read textbooks and many of his students went on to teach natural philosophy at other universities. He first taught a full course on experimental philosophy in 1672 and published its contents under the title Collegium experimentale sive curiosum in 1676. As the title suggests, the book presents a style of experimental philosophy similar to the experimental natural history of the early Royal Society. It is divided into a series of ‘tentamina’, which describe either one experiment, or a series of experiments, or an instrument. What is of particular interest, however, is Sturm’s concern with the way speculative natural philosophy ought to be taught.

Sturm's description of the Torricellian apparatus

He wrote three different books on this subject, which show a development of the manner that he related speculative philosophy to experimentation: the Physica conciliatrix (1684), the Physica electiva sive hypothetica (1697) and finally the Physicae modernae sanioris compendium (1704). In the Physica conciliatrix, Sturm argues for philosophical eclecticism: given the variety of philosophical schools, it was improbable that one was correct in all cases, so speculative philosophy should not be based on one particular school (whether Aristotelian, Cartesian or atomistic), but take all existing hypotheses into account. While experiments would give some guidance in the matter, they could not solve the issue, because experimentation could not explain the causes of the observed phenomena (his earlier discussion of Henry More’s hylarchic spirit in Collegium experimentale exemplifies this issue for him).

The Physica electiva (later re-edited by Christian Wolff) follows on from that position, the search for causes remains the domain of speculative philosophy and cannot be based on one school, precisely because all schools have been shown to be incomplete in their explanations. The eclecticism he develops in this book is one of methodological diversity. Just as mathematics has developed different and unrelated methods that can be applied to different mathematical problems, speculative philosophy needs a variety of methods that provide a way to choose from a range of hypotheses put forward to explain a particular phenomenon.

To achieve this it was necessary to establish the principles on which these methods can be derived and justified, something that had already been established in mathematics. Philosophical analysis had to start with an account of the phenomena in question that was precise and true, but also included all circumstances. Then, all existing hypotheses explaining the phenomena had to be taken into account and analysed. Accounting for all phenomena was to be considered an argument for the truth of the hypothesis, contradiction by a single phenomenon refutes the hypothesis. Yet, even false hypotheses should be discussed further, as their refutation would lead to improved knowledge of the subject matter (see Michael Albrecht’s Eklektik for details on these principles).

While the Physicae modernae compendium was intended as a textbook that would work out this form of natural philosophy, it contains an important methodological development. Whereas the Physica electiva presents the notion of a complete speculative natural philosophy, i.e. a discussion of all known phenomena and the selection of the most probable hypotheses for each phenomenon, the preface of the Physicae modernae compendium restricts the content of ‘textbook natural philosophy’ to those phenomena that can be predicted with certainty.

Not all university philosophers went the route of eclecticism. In my next post, I will discuss the radically different approach that was developed by someone who was acquainted with Sturm from their common student days at Leiden University and later became one of his critics, Burchard de Volder.

David Fordyce’s advice to students

Juan Gomez writes…

I have mentioned the name ‘David Fordyce’ a couple of times in my previous posts. The influence this thinker had in the second half of the eighteenth century (Benjamin Franklin was impresed by his works, though he mistakenly credited them to Hutcheson) usually goes unnoticed, despite the success of his main works. He is also a very good example of the adoption of the rhetoric and methodology of experimental philosophy in the field of moral philosophy.

Fordyce (1711-1751) studied at Marischal College, Aberdeen, in the 1720s (the same decade George Turnbull was a regent there). He came back to his alma mater in 1742 to become a regent himself. During this period he taught, as most regents did, “all the Sciences, Logics, Metaphysics, Pneumatics, Ethics strictly so called & the Principles of the Law of Nature and Nations with natural and experimental Philosophy.” (David Fordyce to Philip Doddridge, 6 June 1743. Quoted in the Liberty Fund edition of his Elements of Moral Philosophy). This was also the period when he published his main works, the Dialogues Concerning Education (1745) and The Elements of Moral Philosophy (1748). The latter was first published as section nine of Robert Dodsley’s The Preceptor (1748), anonymously, and then published posthumously in 1754. The essay had such a good reception that it was used as the text book for moral philosophy lectures in North American universities, and it was used almost in full (only the conclusion was ommitted) for the entry on moral philosophy of the Encyclopaedia Britannica from its first edition until well into the nineteenth century.

A recent edition of the Elements also includes a speech he gave to his students at the start of the year of lectures on moral philosophy, which is the text I want to focus on. The speech is entitled A brief Account of the Nature, Progress, and Origin of Philosophy delivered by the late Mr. David Fordyce, P. P. Marish. Col: Abdn to his Scholars, before they begun their Philosophical course. Besides the explicit use of the terminology of the experimental method in his Elements (induction, hypotheses, deduction of rules from observation, etc.), his speech shows the traits that characterize the methodology of the experimental philosophy. For example:

- “It is evident that setting aside sovreign instruction, true knowledge must be acquired by slow degrees from experience & observation, & that it will always be proportionate to the largeness & extent of our Experience.”

- “The knowledge then of the nature, laws & connections of things is, as has been observed, Philosophy; and they who apply to the study of these, & from thence deduce rules for the conduct & improvement of human life, are Philosophers. They who consider things as they are or as they exist, & draw right conclusions from thence, are true Philosophers. But they who without regard to fact or nature indulge themselves in framing systems to which they afterwards reduce all appearances, are, notwithstanding their ingenuity & subtilty, to be reckoned only the corrupters & enemies of true learning.”

- “Now there is a natural & proper method of attaining to true knowledge as well as any other accomplishment, which if neglected must occasion error & contradiction. It cannot be too often repeated, that there is no real knowledge, nor any that can answer a valuable End, but what is gathered or Copyed from nature or from things themselves. That the knowledge of Nature is nothing else than the knowledge of facts or realities & their established connections. That no Rules or Precepts of life Can be given or any Scheme of Conduct prescribed, but what must suppose a settled Course of things conducted in a regular uniform manner. That in order to denominate those Rules just, & to render those Schemes successful, the Course of things must be understood & observed. & that all Philosophy, even the most didactic & practical parts of it, must be drawn from the Observation of things or at least resolved into it; Or which is the same thing, that the knowledge of truth is the knowledge of Fact, & whatever Speculations are not reduceable to the one or the other of these are Chimerical, Vague & uncertain.”

The previous are just the most telling quotes, but the whole overview Fordyce gives of the history of philosophy embodies the anti-Aristotelian, anti-hypothetical attitude of the experimental philosophy. Such was the message Fordyce delivered as a regent to his students in the 1740s, highlighting the relevance of the experimental/ speculative distinction, with the former being the only appropriate method for the progress of knowledge.

That’s it for now, but stay tuned to our blog. Pretty soon we will have a guest post by Dr. Gerhard Wiesenfeldt on a topic closely related to Fordyce’s speech: early modern universities and experimental philosophy.

Tetens on Experimental vs Speculative Philosophy

Alberto Vanzo writes…

A couple of weeks ago, I introduced Christian Wolff as an example of knowledge of experimental philosophy in Germany during the first half of the eighteenth century. Wolff knew, among others, Boyle’s, Hooke’s, and Locke’s works and he criticized Newton’s rejection of hypotheses in the field of natural philosophy.

However, the fact that Wolff knew leading experimental philosophers does not mean that he regarded them all as exponents of one and same the movement of experimental philosophy. Did eighteenth century German philosophers identify a continuous tradition of experimental philosophy? If so, what did they regard as the distinctive features of that tradition? What authors did they regard as its representatives?

Johann Nicolaus Tetens

Today I am going to sketch the answers that Johann Nicolaus Tetens gave to these questions. Tetens was one of the brightest minds in Germany in the second half of the eighteenth century. The essay on which I am going to focus was published in 1775, six years before Kant’s first Critique. It is entitled On General Speculative Philosophy. It contrasts speculative philosophy [speculativische Philosophie] with observational philosophy [beobachtende Philosophie].

Observational philosophy is a philosophy which relies on observation. Observation, in the relevant sense, is a form of introspection. It takes place when we disregard the relation of our mental representations with the objects they are about and we regard our mental representations as “something subjective, modifications of ourselves”. Observation enables us to discover truths about God, the human soul, and the world, to which we have access

- without previous general speculations on substance, space and time, etc. […] Reid, Home, Beattie, Oswald, and also several German philosophers have proven this beyond doubt with their reasonings and with the proofs that they have put forward.

This passage makes clear that Tetens’ observational philosophy is actually Scottish common sense philosophy – a movement that had a great influence in Germany in the 1770s. Scottish common sense philosophy was an incarnation of experimental philosophy. Tetens’ contrast between observational and speculative philosophy is a version of the experimental-speculative distinction.

According to Tetens, common sense and introspection provide us with a stock of hypotheses and intuitions. These form “the terrain that one must cultivate when doing speculative philosophy.” Speculative philosophers must reformulate those intuitions in well-defined terms, look for systematic links between them, assess their truth, seek for reasons to believe them to be true, and so on. The philosophy that Tetens advocates in 1775 combines an initial observational stage with a later speculative stage.

According to Tetens, this means combining the virtues of British and German philosophy. Tetens regards observational philosophy as a distinctively British movement (with French and German followers) and speculative philosophy as a distinctively German tradition:

- British philosophers could be our models in observing; but they should not be our models in speculative philosophy. … New [British] philosophy was first shaped by Bacon and later by Locke. […] Bacon’s [New] Organon, regarded as a set of directions to perform observations and to extend empirical knowledge, is a masterwork … Locke’s books on the human understanding contain an excellent model for employing that method in the knowledge of our soul and its operations. Yet both of their logics are insufficient on the other side [scil. the speculative side] … British philosophy was nearly only an observational philosophy, an empirical physics of man.

Tetens identifies a continuous tradition of experimental (or in his terms, observational) philosophers stretching from Bacon to Reid, through Locke, Hume, and Condillac. This shows that the existence of a tradition of experimental philosophy and its opposition with speculative philosophy (ESP) were known to Kant’s contemporaries in the mid-1770s.

Over the following two decades, Kant adumbrated a new distinction between empiricism and rationalism. His followers (Reinhold, Tennemann) chose to privilege it over the ESP that they could find in Tetens’ text from 1775 (and elsewhere). Given their knowledge of the ESP, their choice to privilege the new distinction between empiricism and rationalism must have been a deliberate one. What reasons motivated that choice? Do let me know your thoughts in the comments!

Baconian versus Newtonian experimental philosophy

Peter Anstey writes…

Eric Schliesser’s comments about the utility of the experimental/speculative distinction, provide an opportunity for me to lay out a distinction that is absolutely central to our project. But let’s hear from Eric first: I quote from his blog post on It’s Only a Theory:

- It ignores at least one other group of philosophers, namely those that believed in (mathematical) theory mediated measurement. I am thinking of Galileo, Huygens, and Newton, among the best known. These are not best described as experimental, although all were accomplished experimentalists (and Newton’s Optics is often assimilated to experimental traditions), but their work has very different character from say, Bacon or Boyle. (They are also not best described as speculative, because all three practiced a self-restraint on published speculation.) Certainly after the Principia this approach created standing challenge to all other forms of philosophizing. So the Otago framework will run into big trouble in 18th century.

We’ve already shown that, in fact, the terminology of the experimental philosophy is very prevalent in the 18th century and, moreover, that the experimental philosophy was extended beyond natural philosophy into moral philosophy and even aesthetics. See, for example, the works of George Turnbull which are a good example of experimental moral philosophy.

But the important issue Eric raises has to do with those who practised ‘theory mediated measurement’ such as Galileo, Huygens and Newton. What our research has shown is that the experimental philosophy was practised in two quite different ways. Up until the 1690s, Boyle, Hooke and the early Royal Society practised experimental philosophy according to the method of Baconian natural history. However, from the last decade of the seventeenth century Newton’s new mathematical natural philosophical method came to be seen as the preferred method of experimental philosophy. The Baconian natural history program started to run out of steam in the 1690s and it soon came to be replaced by the Newtonian method. This is, in fact, the explanation of Newton’s common refrain ‘Natural philosophy is not natural history’. And Newton himself had a large hand in the demise of the Baconian approach to experimental philosophy both through criticism and through his own positive alternative. Far from providing an exception to our framework, Newton, the self-confessed experimental philosopher, is one of the central players!

Experiment and Hypothesis, Theory and Observation: Wolff vs Newton

Alberto Vanzo writes…

Looking for sources for knowledge of experimental philosophy in eighteenth century Germany, I found some interesting texts by relatively unknown authors (at least beyond the circle of specialists). Christian Wolff is one of them. He was the most famous German philosopher in the first half of the eighteenth century. His philosophy was taught in many universities and his works were very popular. For instance, his German Logic knew no less than 14 editions during Wolff’s life.

Wolff knew several British experimental philosophers. He cited works by Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke, he was the Locke reviewer for an important journal (the Acta eruditorum), and he polemized with the Newtonian John Keill on the existence of the vacuum. He is a good example of the fact that German thinkers were acquainted with the works and the methodological views of British experimental philosophers in the first half of the eighteenth century.

A number of Wolff’s statements might make us think that he was himself an adherent to the early modern version of x-phi. Like British experimental philosophers, Wolff criticizes Descartes’ attempt to explain a great variety of natural phenomena in the light of few general principles that he established a priori. Like Hume and Hutcheson, Wolff is eager to extend the dominion of experimental philosophy beyond the boundaries of physics. He projects the disciplines of experimental cosmology, experimental teleology, experimental theology, experimental politics, and even experimental ontology. For his philosophical system as a whole, he chooses the name of “universal experimental philosophy” (philosophia experimentalis universalis). How could Wolff have been a more enthusiastic adherent to the program of experimental philosophy?

Yet contrary to the appearances, Wolff’s views were quite different from those of his British counterparts. This can be seen by comparing him with Newton. Newton, like virtually every other early modern experimental philosopher, claimed that he did not feign any hypothesis (his famous hypotheses non fingo). Wolff rebuts that Newton

- indulges in hypotheses in those very areas in which they think he abstained from employing them […] In fact, what else is universal attraction or gravity, which is represented by a measure of attraction, if not a hypothesis which is assumed because of certain phenomena and then is extended to all matter?

According to Wolff, not only did Newton feign hypotheses, but he did well to do so. This is because natural philosophers must proceed like astronomers:

Christian Wolff

From some present events, they infer what they have to assume, in order for [the events] to follow [from it], and they posit that their hypothesis applies to all [similar] events […] To determine whether they did well to assume the hypothesis, they infer what follows from it on the basis of a correct reasoning, in order to compare it with the remaining events that they have either observed, or that they derive from observations. [They do this] in order to see whether what has been observed agrees with the hypothesis. If they find that [observations and hypothesis] are in contrast with one another, then they improve the hypothesis, and in this way they constantly move closer to the truth.

Wolff holds that there is a circular relationship between observation or experiment on the one hand, and theory on the other hand. He stresses

- how much theory owes to observations and how much, on the other hand, observations owe to theory, since observations perfect theory and theory in turn continuously perfects observations. He who is ignorant of any theory and does not have much ability to use the faculty of knowing will only discover obvious and mostly imprecise [truths] on the basis of observations. There would not be much progress, unless one could presuppose some theory; and the more [a theory] is developed, the more discoveries one will make by means of observation[s].

Unlike Newton, Wolff was no great scientist. However, the quotes above suggest that his methodology of science is worth a serious reading. His acknowledgments of the interaction between theory and observation sound modern. They sketch a version of the hypothetico-deductive method that might provide an interesting alternative to Newton’s strict inductivism.

In summary, Wolff is a good example of the Germans’ knowledge of British experimental philosophy in the first half of the eighteenth century. His views are also interesting in their own right. So are Johann Nicolaus Tetens’ comments on observational vs speculative philosophy or Johann Heinrich Lambert’s distinction between theory-testing experiments and experiments that have a life of their own – two hundred years before Ian Hacking. More on this another time.

In the next post, Kirsten will discuss Newton’s method, in particular his rejection of hypotheses and his use of queries. See you next Monday!

Turnbull and the ‘spirit’ of the experimental method

Juan Gomez writes…

You will probably recognize the following phrase: ‘An attempt to introduce the experimental Method of Reasoning into moral Subjects.’ It is the subtitle of David Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature of 1739-40, and the first explicit mention of the application of the experimental method in moral topics. Many scholars have pointed to it, and claimed that Hume was the first one to go forward with this attempt. However, others (Tom Beauchamp, Alexander Broadie) have also noticed that this idea did not originate with Hume. I will show here that the ‘spirit’ of the experimental method was very much alive at least 20 years before the publication of Hume’s Treatise. In fact, contrary to the most commonly held view, Hume should not be the reference point when studying the emergence of the “science of man”. Rather, we should look at the Aberdeen philosophers, in particular at George Turnbull and his lectures at Marischal College in the 1720’s.

I will make a prima facie case for this claim with only a few quotes (available in this document), but please do contact me if you are interested in the topic, since there is more than enough evidence that I would be happy to discuss with you.

To begin with, Hume was not the first to allude to the application of the experimental method in moral philosophy. Francis Hutcheson had already done this in his 1725 Inquiry. The subtitle of this work explains that it contains the following:

- the Principles of the late Earl of Shaftesbury are explained and defended against the Fable of the Bees; and the Ideas of Moral Good and Evil are established, according to the Sentiments of the Ancient Moralists, with an attempt to introduce a Mathematical Calculation on subjects of Morality. (emphasis added)

Hutcheson doesn’t use the words ‘experimental method’, but saying that he will give a ‘mathematical calculation on subjects of morality’ is perfectly in line with the spirit of the experimental method (specifically with the Newtonian method). To be fair to Hume, he does recognize Hutcheson as one of the philosophers who has “begun to put the science of man on a new footing.” (Treatise (1739), Introduction, p. 6-7) So Hume might have recognized that he was not the first, but a number of modern scholars have not.

Moving on to George Turnbull, whom I believe is mistakenly underrated as a figure of the Scottish Enlightenment, published his Principles of Moral Philosophy in 1740, the same year Hume published the third volume of his Treatise, which is on Morals. This would at least lead us to think that both Hume and Turnbull were working on the application of the experimental method in morality at the same time. But as Turnbull mentions in the introduction to his Principles, his book is based on the lectures he gave at Marischal College between 1721 and 1726, around the time when Hume was a student at the University of Edinburgh. Besides the numerous remarks in the Principles that show Turnbull’s devotion to the experimental method, there is a key document that shows that he was teaching the young Aberdeen students the moral philosophy he explains in the book he published 17 years later. The document is the 1723 graduation thesis, which the graduating students (Thomas Reid among them) had to defend, titled De scientiae naturalis cum philosophia morali conjunctione (On the unity of natural science and moral philosophy).

I am currently working on the 1723 thesis, and at this moment I can let you know that it is strengthening my belief in the importance of Turnbull in the development of the ‘science of man.’ For now I’ll leave you with enough quotes from the Principles that show that if we want to study the development of the science of morals, we should start focusing more on Turnbull and Aberdeen, and less on Hume and Edinburgh.