Early Modern Philosophy at the AAP

The Annual Conference of the Australasian Association of Philosophy will start in 10 days and the abstracts have just been published. We were very pleased to see that there are plenty of papers on early modern philosophy. We are re-posting the abstracts below.

As you will see, Juan, Kirsten, Peter, and I are presenting papers on early modern x-phi and the origins of empiricism. Come and say hi if you’re attending the conference. If you aren’t, but would like to read our papers, let us know and we’ll be happy to send you a draft. Our email addresses are listed here. We’d love to hear your feedback.

Peter Anstey, The Origins of Early Modern Experimental Philosophy

This paper investigates the origins of the distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy (ESP) in the mid-seventeenth century. It argues that there is a significant prehistory to the distinction in the analogous division between operative and speculative philosophy, which is commonly found in late scholastic philosophy and can be traced back via Aquinas to Aristotle. It is argued, however, the ESP is discontinuous with this operative/speculative distinction in a number of important respects. For example, the latter pertains to philosophy in general and not to natural philosophy in particular. Moreover, in the late Renaissance operative philosophy included ethics, politics and oeconomy and not observation and experiment – the things which came to be considered constitutive of the experimental philosophy. It is also argued that Francis Bacon’s mature division of the sciences, which includes a distinction in natural philosophy between the operative and the speculative, is too dissimilar from the ESP to have been an adumbration of this later distinction. No conclusion is drawn as to when exactly the ESP emerged, but a series of important developments that led to its distinctive character are surveyed.

Russell Blackford, Back to Locke: Freedom of Religion and the Secular State

For Locke, religious persecution was the problem – and a secular state apparatus was the solution. Locke argued that there were independent reasons for the state to confine its attention to “”civil interests”” or interests in “”the things of this world””. If it did so, it would not to motivated to impose a favoured religion or to persecute disfavoured ones. Taken to its logical conclusion, this approach has implications that Locke would have found unpalatable. We, however, need not hesitate to accept them.

Michael Couch, Hume’s Philosophy of Education

Hume has rarely been considered a contributor to the philosophy of education, which is unsurprising as he did not write a dedicated treastise nor make large specific comment, and so educators and philosophers have focused their attention elsewhere. However, I argue that a more careful reading of his works reveals that education is a significant concern, specificially of enriching the minds of particular people. I argue that his educational ideas occupy an important, although not major, place in his writings, and also an important place in the history of ideas as Hume fills a gap after Locke, and provides the framework for the much more educationally influential Bentham and Mill.

Gillian Crozier, Feyerabend on Newton: A defense of Newton’s empiricist method

In “Classical Empiricism,” Paul Feyerabend draws an analogy between Isaac Newton’s empiricist methodology and the Protestant faith’s primary tenet sola scriptura. He argues that the former – which dictates that ‘experience’ or the ‘book of nature’ is the sole justified basis for all knowledge of the external world – and the latter – which dictates that the sole justified basis for all religious understanding is Scripture – are equally vacuous. Feyerabend contends that Newton’s empiricism, which postures that experience is the sole legitimate foundation of scientific beliefs, serves to disguise supplementary background assumptions that are not observer-neutral but are steeped in tradition, dogma, and socio-cultural factors. He focuses on Newton’s treatment of perturbations in the Moon’s orbit, arguing that this typifies how Newton supports his theory by cherry-picking illustrations and pruning them of anomalies through the incorporation of ad hoc assumptions. We defend Newton’s notion of empirical success, arguing that Newton’s treatment of the variational inequality in the lunar orbit significantly adds to the empirical success a rival hypothesis would have to overcome.

Simon Duffy, The ‘Vindication’ of Leibniz’s Account of the Differential. A Response to Somers-Hall

In a recent article in Continental Philosophy Review, entitled ‘Hegel and Deleuze on the metaphysical interpretation of the calculus,’ Henry Somers-Hall claims that ‘the Leibnizian interpretation of the calculus, which relies on infinitely small quantities is rejected by Deleuze’(Somers-Hall 2010, 567). It is important to clarify that this claim does not entail the rejection of Leibniz’s infinitesimal, which Leibniz considered to be a useful fiction, and which continues to play a part in Deleuze’s account of the metaphysics of the calculus. In order to further clarify the terms of this debate, I will take up two further issues with Somers-Hall’s presentation of Deleuze’s account of the calculus. The first is with the way that recent work on Deleuze’s account of the calculus is reduced to what Somers-Hall refers to as ‘modern interpretations of the calculus,’ by which he means set-theoretical accounts. The second is that this reduction by Somers-Hall of ‘modern interpretations of the calculus’ to set-theoretical accounts means that his presentation of Deleuze’s account of the calculus is only partial, and the partial character of his presentation leads him to make a number of unnecessary presumptions about the presentation of Deleuze’s account of the ‘metaphysics of the calculus’.

Sandra Field, Spinoza and Radical Democracy

Antonio Negri’s radical democratic interpretation of Benedictus de Spinoza’s political philosophy has received much attention in recent years. Its central contention is that Spinoza considers the democratic multitude to have an inherent ethical power capable of grounding a just politics. In this paper, I argue to the contrary that such an interpretation gets Spinoza back to front: the ethical power of the multitude is the result of a just and fair political institutional order, not its cause. The consequences of my argument extend beyond Spinoza studies. For Spinoza gives a compelling argument for his rejection of a politics relying on the virtue of a mass subject; for him, such a politics substitutes moral posturing for understanding, and fails to grasp the determinate causes of the pathologies of human social order. Radical democrats hoping to achieve effective change would do well to lay aside a romanticised notion of the multitude and pay attention to the more mundane question of institutional design.

Juan Gomez, Hume’s Four Dissertations: Revisiting the Essay on Taste

Sixteen years ago a number of papers and discussions considering Hume’s essay on taste emerged in various journals. They deal with a number of issues that have been commonly thought to arise from the argument of the essay: some authors take Hume to be proposing two different standards of taste, other think that his argument is circular, and other focus on the role the standard and the critics play in Hume’s theory. I believe that all the issues that have been identified arise from a reading of the essay that takes it out of its context of publication, and mistakes Hume’s purpose in the essay. In this paper I want to propose an interpretation of the essay on taste that takes into account two key aspects: the unity of the dissertations that were published along with the essay on taste in 1757, under the title of Four Dissertations, and Hume’s commitment to the Experimental Philosophy of the early modern period. I believe that these two contextual aspects of the essay provide a reading of the essay on taste that besides solving the identified issues, gives us a good idea of its aim and purposes.

Jack MacIntosh, Models and Methods in the Early Modern Period: 4 case studies

In this paper I consider the various roles of models in early modern natural philosophy by looking at four central cases: Marten on the germ theory of disease. Descartes, Boyle and Hobbes on the spring of the air; The calorific atomists, Digby, Galileo, et al. versus the kinetic theorists such as Boyle on heat and cold; and Descartes, Boyle and Hooke on perception. Did models in the early modern period have explanatory power? Were they taken literally? Did they have a heuristic function? Unsurprisingly, perhaps, consideration of these four cases (along with a brief look at some others) leads to the conclusion that the answer to each of these questions is yes, no, or sometimes, depending on the model, and the modeller, in question. I consider briefly the relations among these different uses of models, and the role that such models played in the methodology of the ‘new philosophy.’ Alan Gabbey has suggested an interesting threefold distinction among explanatory types in the early modern period, and I consider, briefly, the way in which his classification scheme interacts with the one these cases suggest.

Kari Refsdal, Kant on Rational Agency as Free Agency

Kant argued for a close relationship between rational, moral, and free agency. Moral agency is explained in terms of rational and free agency. Many critics have objected that Kant’s view makes it inconceivable how we could freely act against the moral law – i.e., how we could freely act immorally. But of course we can! Henry Allison interprets Kant so as to make his view compatible with our freedom to violate the moral law. In this talk, I shall argue that Allison’s interpretation is anachronistic. Allison’s distinction between freedom as spontaneity and freedom as autonomy superimposes on Kant a contemporary conception of the person. Thus, Allison does not succeed in explaining how an agent can freely act against the moral law within a Kantian framework.

Alberto Vanzo, Rationalism and Empiricism in the Historiography of Early Modern Philosophy

According to standard histories of philosophy, the early modern period was dominated by the struggle between Descartes’, Spinoza’s, and Leibniz’s Continental Rationalism and Locke’s, Berkeley’s, and Hume’s British Empiricism. The paper traces the origins of this account of early modern philosophy and questions the assumptions underlying it.

Kirsten Walsh, Structural Realism, the Law-Constitutive Approach and Newton’s Epistemic Asymmetry

In his famous pronouncement, Hypotheses non fingo, Newton reveals a distinctive feature of his methodology: namely, he has asymmetrical epistemic commitments. He prioritises theories over hypotheses, physical properties over the nature of phenomena, and laws over matter. What do Newton’s epistemic commitments tell us about his ontological commitments? I examine two possible interpretations of Newton’s epistemic asymmetry: Worrall’s Structural Realism and Brading’s Law-Constitutive Approach. I argue that, while both interpretations provide useful insights into Newton’s ontological commitment to theories, physical properties and laws, only Brading’s interpretation sheds light on Newton’s ontological commitment to hypotheses, nature and matter.

Eric Watkins on Experimental Philosophy in Eighteenth-Century Germany

Eric Watkins writes…

Having commented on two of Alberto Vanzo’s papers at the symposium recently held in Otago, I am happy to post an abbreviated version of my comments. The basic topic of Alberto’s papers is the extent to which one can see evidence of the experimental – speculative philosophy distinction (ESD) in two different periods in Germany, one from the 1720s through the 1740s, when Wolff was a dominant figure, and then another from the mid 1770s through the 1790s, when Tetens, Lossius, Feder, Kant, and Reinhold were all active. Alberto argues that though Wolff was aware of the works of many of the proponents of experimental philosophy and emphasized the importance of basing at least some principles on experience and experiments, he is not a pure advocate of either experimental or speculative philosophy. He then argues that some of the later figures, specifically Tetens, Lossius, Feder and various popular philosophers, undertook projects that could potentially be aligned with ESD, while others, such as Reinhold and later German Idealists, consciously rejected it, opting for the rationalism-empiricism distinction (RED) instead, which was better suited to their own agenda as well as to that of their German Idealist successors. As a result, Alberto concludes that ESD was an option available to many German thinkers, but that experimental philosophy was not a dominant intellectual movement, as it was in England and elsewhere.

I am in basic agreement with Alberto’s main claims, but I’d like to supplement the account he offers just a bit with a broader historical perspective. Two points about Wolff. First, when Wolff tries to address how the historical knowledge relates to the philosophical knowledge, which can be fully a priori, it is unclear how his account is supposed to go. As Alberto points out, Wolff thinks that data collection and theory building are interdependent, but he also thinks that we can have a priori knowledge. It’s simply not clear how these two positions are really consistent and Wolff does not, to my mind, ever address the issue clearly enough. So I am inclined to think that Wolff is actually ambiguous on a point that lies at the very heart of ESD.

Second, though Wolff was certainly a dominant figure in Germany, he is of course also not the only person of note. For one, throughout the course of the 18th century, experimental disciplines became much more widespread in Germany. So, in charting the shape and scope of ESD at the time, it would be useful to see what conceptions of knowledge and scientific methodology university professors in physics, physiology, botany, and chemistry had, if any. For another, after the resurrection of the Prussian Academy of Sciences by Frederick the Great in 1740, a number of very accomplished figures with reputations of European-wide stature, such as Leonhard Euler, Maupertuis, and Voltaire, came to ply their trade in Berlin. Virtually all of them were quite interested in experimental disciplines and several were extremely hostile towards Wolff. It would therefore be worth considering the full range of their activities to get a sense of their views on ESD.

Let me now turn to the later time period. As Alberto argued, Kant isn’t exactly the right figure to look to for the origin of the RED. Kant does not typically contrast empiricism with rationalism. Instead, when it comes to question of method and the proper use of reason, Kant’s clearest statements in the Doctrine of Method are that the fundamental views are that of dogmatism (Leibniz), skepticism (Hume), indifferentism (popular philosophers), and finally the critique of pure reason, positions that do not line up neatly with either RED or ESD.

However, it would be hasty to infer that there is no significant element of ESD in Kant. Kant dedicates the Critique of Pure Reason to Bacon, an inspiration to many of the British experimentalists. More importantly, one should keep in mind whom Kant is attacking in the first Critique, namely proponents of pure reason who use reason independently of the deliverances of the senses in their speculative endeavors. In many of these instances, the term “speculative” is synonymous with “theoretical” and is contrasted with “practical”. However, in many others Kant is indicating a use of reason that is independent of what is given through our senses, and on that issue, it is a major thrust of Kant’s entire Critical project to show that the purely speculative use of reason (pure reason) cannot deliver knowledge. In this sense, his basic project reveals fundamental similarities with experimental philosophers.

Now the British experimental philosophers would presumably object to synthetic a priori knowledge on the grounds that this is precisely the kind of philosophical speculation that one ought to avoid. But Kant would respond that he is attempting to show that experiments in particular, and experience in general, have substantive rational presuppositions, a possibility that cannot be dismissed out of hand, given its intimate connection to what the experimental philosophers hold dear. This is one of the novel and unexpected twists that make Kant’s position so interesting. So one could incorporate Kant into the ESD narrative by arguing that he is trying to save the spirit of the experimentalists against those who are overly enamored with speculation while still allowing for rational elements. On this account, then, Kant would be responding directly to the ESD, namely by trying to save it, albeit in an extremely abstract and fundamental way that original proponents of the view could never have anticipated.

ESP: Is It Really Best?

Alberto Vanzo writes…

One of the mantras of our research team is: ESP is best. But is it?

As those of you who have been reading the blog for a while will know, we are not supporting Extra-Sensory Phenomena. We are claiming that we can make better sense of a number of episodes in the history of early modern thought by reading them in the light of the distinction between Experimental and Speculative Philosophy than in the light of the empiricism-rationalism distinction.

Keith Hutchison is less than convinced. If he is correct, we’d be better off putting away our early modern x-phi hats and start working on some other idea. Should we? We’d love to know what you think, so today I’m posting Keith’s comment along with a reply.

Keith says:

- Alberto’s paper told me something very helpful about the proposal to replace the RED [rationalism-empiricism distinction] with the ESP. For it is clear that Alberto interprets ‘experimentalism’ very widely, so widely indeed that he would count (say) the observational astronomy of the eighteenth-century as ‘experimental’. In fact, he seems to use the word to mean what I routinely call ‘empiricism’. Apparently there are two senses of ’empiricism’, one a very narrow conception endorsed by that coterie of historians of thought secluded within the halls of philosophy departments, and the other a more general one, as used widely within the thinking public. It is this second notion that the Otago team propose to call ‘experimentalism’. This seems to me a very dangerous practice, one that would generate much confusion if it spread. For it clashes with one of the key connotations of the word ‘experiment’, the idea that experiments constitute a special sub-class of empirical enquiries, those that involve an experimenter, who deliberately manipulates the entities under investigation. This is the way the word is used in modern English, and it is the way the word was used in seventeenth-century English – when such experimentalism became philosophically respectable. To start using it in a radically new sense, just to avoid a problem created by the way a tiny handful of writers have (mis-?)used the word ‘empirical’ is surely mischievous.

Keith is right when he points out that, in the expression “experimental philosophy”, the adjective “experimental” does not uniquely refer to experiments. But this is in line with seventeenth-century usage. When authors like Dunton (here) and Diderot (here), spoke of the experimental philosophy or the experimental method, they did not uniquely refer to experiments. They referred to a specific way of studying the nature of the world around us and our own human nature. To understand it, experimental philosophers claimed, we cannot rely on demonstrative reasonings from principles or hypotheses lacking a broad empirical support. Instead, we must make extensive and systematic recourse on experiments and observations.

When self-declared experimental philosophers studied the human mind, they were adamant that the observations on which they rely included introspection. Juan has showed this in a post on Reid. Indeed, although some early modern authors distinguished between experiments and observations, they performed the same role within Boyle’s or Hooke’s conception of knowledge acquisition. This is why German experimental philosophers could translate “experimental philosophy” as “observational philosophy”.

So as Keith points out, in the expression “experimental philosophy”, the term “experimental” has a broad meaning. However, this is not to say that the expression “experimental philosophy” is irremediably vague or identical to a broad notion of “empiricism”. First, the self-declared early modern experimental philosophers told us what the method of experimental philosophy was. Second, authors like Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke put that method in practice in their natural-philosophical work. Third, experimental philosophy can be seen as a movement that people adhered to: they stated that they were part of that movement; they endorsed its rhetoric; they identified with its heroes (e.g., Bacon) and attacked its foes (e.g., Aristotle). When we trace the history of early modern x-phi, we are not applying notions that we have first introduced. We are taking seriously their statements on how they were studying the nature of the world and of our mind, and seeing if it is possible to better understand what they were doing by placing them within the movement that they were actually involved in than by using either the vague or the more technical notions of empiricism that can be found in the literature.

So what do you think: is ESP best? Or are we on a wrong track?

Anik Waldow on ‘Jean Le Rond d’Alembert and the experimental philosophy’

Anik Waldow writes …

Peter Anstey’s essay “Jean Le Rond d’Alembert and the experimental philosophy” sets out to confirm his claim that the distinction between experimental philosophy and speculative philosophy “provided the dominant terms of reference for early modern philosophy before Kant” (p.1) by examining the Preliminary Discourse of the Encyclopédie. Anstey comes to the conclusion that d’Alembert, who identified metaphysical speculation as the reason why experimental science had “hardly progressed” (p.3), was highly influenced by Locke and clearly reflected Newton’s anti-hypothetical stance.

The paper contains two major lines of argument, which are interconnected but possess slightly different focuses. The first is concerned with the correction of our understanding of particular philosophers and their commitment to the experimental tradition of Locke, Boyle and Newton. The second intends to alter the way we approach the history of philosophy. In this context Peter’s discussion of d’Alembert amounts to a defense of a new conceptual scheme that ought to replace the rationalist/empiricist distinction, thus enabling us to correct our knowledge of early modern philosophy in general. I will merely focus here on the first of these two points, leaving my worries concerning Anstey’s suggestion that Newton’s own experimental practice is able to clearly demarcate the line between experimental and speculative natural philosophy for another occasion.

Much of Anstey’s essay hinges on the claim that d’Alembert’s own rational mechanics is not hostile to experimentalism, but “an extreme application of the new Newtonian mathematical method that came to predominate the manner in which the experimental philosophy was understood in the mid-eighteenth century.” (p. 12) Rational mechanics is a discipline committed to an a priori methodology that seems to be diametrically opposed to the inductive practice of the experimenter and her strict quantitative treatment of observable phenomena. And even though one may argue that experiments are in some restricted sense relevant to rational mechanics, it is clear that this discipline is not committed to the kind of “systematic collection of experiments and observations” (Preliminary Discourse to the Encyclopedia of Diderot, trans and intro. Richard N. Schwab, Chicago,1995, p.24) that d’Alembert regards as the defining feature of experimental physics. To identify d’Alembert as a defender of experimentalism therefore requires Anstey to show that there is no contradiction involved in practising rational mechanics, on the one hand, and defending Lockean experimentalism, on the other.

Anstey’s argument is convincing as long as natural philosophy is treated as a whole that is able to integrate various methodologies. In this form the argument makes a good case against the rigid dichotomies that the rationalist/empiricist distinction introduces, because it shows that we need not endorse what I call an ‘either-or conception’ of experimentalism: either we are experimenters and reject rational mechanics as a speculative discipline because of its detachment from observable phenomena; or we conceive of natural philosophy as a broadly mathematical enterprise and attack experimentalism for its lack of scientific rigour.

Having said that, however, I should like to raise the following question. How well supported is Anstey’s claim that d’Alembert believed that rational mechanics, and in particular demonstrative reasoning, was not merely compatible with experimentalism, but an integral part of it? The reason I ask this question is that we must distinguish between two positions: the first accepts demonstrative mathematics as a methodology in an area of natural philosophy that, strictly speaking, does not qualify as experimental in itself; the second endorses the claim that all natural philosophy ought to be experimental. Hence, the first position regards experimentalism as a specific branch of natural philosophy, while the second takes the whole of natural philosophy to be committed to the tenets of experimentalism.

By aligning d’Alembert’s own methodology with Newton’s mathematized experimentalism, Anstey suggests that d’Alembert was a proponent of the second position. However, I think that d’Alembert’s conception of rational mechanics as the queen among the various natural philosophical disciplines reveals him to be more inclined to the first position. In thinking of rational mechanics as taking the lead in the generation of natural philosophical knowledge, d’Alembert turns experimentalism (conceived as the systematic collection of experiments and observations) into no more than a useful addition to a natural philosophical practice firmly rested on a priori reasoning. Experimentalism is here appreciated only in so far as it is able to generate solutions to problems where rational mechanics can advance no further. Or slightly differently put, experimentalism is acknowledged for its usefulness, but far from being regarded as the discipline that gives the whole of natural philosophy its tone and direction.

In short, Anstey’s paper may have shown that d’Alembert sympathized with Lockean experimentalism. However, more needs to be said in order to clarify how it is possible to think of rational mechanics as a discipline that is, in and of itself, experimental in spirit. Otherwise it is hard to see why we should agree with Anstey’s claim that d’Alembert thought of the whole of natural philosophy as an essentially experimental discipline.

Images of Experimental Philosophy (and a request for help!)

Kirsten Walsh writes…

Over the last few weeks, we have been organizing a rare book exhibition* on the history of experimental philosophy. It has been a privilege to handle dozens of antique books such as a 2nd edition of Newton’s Principia, Bacon’s Opuscula and Kepler’s Epitome. One of the striking features of early modern books is their ornate frontispieces and detailed illustrations. They give the impression that publishers spent a lot of money to acquire and print these images. This got us thinking about what images really capture the spirit of the experimental philosophy. So this week, we thought we’d do a special post on images of experimental philosophy.

One of my favourite images is Wright’s 1768 ‘An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump’. It combines several aspects of the 18th century scientific pursuit: the experimenter as a ‘show man’, natural philosophy as ‘family entertainment’, and Boyle’s air pump centre stage. If you want to see some of the experiments that Wright’s subjects might have seen, have a look at the video on air pressure over at Discovering Science.

Wright (1768), 'An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump'

Another wonderful image is Stradanus’ (1580), ‘Lapis Polaris Magnes’, also known as ‘The Philosopher in his Chamber Studying a Lodestone’.

- “the scholar in his study is surrounded by the new instruments of navigation, drafting, and surveying. An armillary sphere, a compass, an octant, several books, and other measuring tools sit on the table at left. In the left foreground, a lodestone floats on a raft of wood in a wine cooler. The model galleon suspended from the ceiling contrasts to the single-masted, oared Mediterranean vessel that can be seen through the window. The juxtaposition of instruments and books on the scholar’s desk indicates the coming together of the hitherto generally separate traditions of practice and theory. Out of their union, the new experimental philosophy emerged.” (From Experience and Experiment in Early Modern Europe.)

Stradanus (1580), ‘Lapis Polaris Magnes’

Another gallon is represented in the frontispice of Bacon’s De augmentis. It has passed through the Pillars of Hercules, venturing into the unknown and increasing our knowledge. The line beneath the ship explains: “Many shall pass through and learning shall be increased” (“Multi pertransibunt & augebitur scientia”). How shall learning be increased? By overcoming a series of oppositions: between reason and experience (the motto at the top reads “Reason and Experience have been allied together”); between the visible world and the intelligible world (the two globes at the top); between science and philosophy (the two terms at the bottom of the pillars); and even between Oxford and Cambridge (“Oxonium” and “Cantabrigia”)!

Bacon (1640), 'De Augmentis Scientiarum'

The frontispiece to Voltaire’s (1738) Elemens is not a good representation of the experimental philosophy, but it is a lovely illustration. Voltaire sits at his desk, translating Newton’s Principia. Heavenly light seems to come from Newton himself, representing his divine inspiration. The light is reflected downwards to illuminate Voltaire’s work by Voltaire’s lover and muse Émilie du Châtelet (but it was really she who translated Principia and helped Voltaire to make sense of the work).

Voltaire (1738), 'Elemens de la philosophie de Neuton'

West’s (1816) painting depicts Benjamin Franklin’s famous (or infamous) kite experiment. In 1752, Franklin flew a kite in a storm to demonstrate that lightning is a form of electricity. He almost electrocuted himself!

- “As soon as any of the thunder clouds come over the kite, the pointed wire will draw the electric fire from them, and the kite, with all the twine, will be electrified, and the loose filaments of the twine, will stand out every way, and be attracted by an approaching finger. And when the rain has wetted the kite and twine, so that it can conduct the electric fire freely, you will find it stream out plentifully from the key on the approach of your knuckle. At this key the phial may be charged: and from electric fire thus obtained, spirits may be kindled, and all the other electric experiments be performed, which are usually done by the help of a rubbed glass globe or tube, and thereby the sameness of the electric matter with that of lightning completely demonstrated.” (Written by Benjamin Franklin to Peter Collinson, October 19, 1752.)

You can read more about Franklin’s work on electricity at Skulls in the Stars.

West (1816), 'Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky'

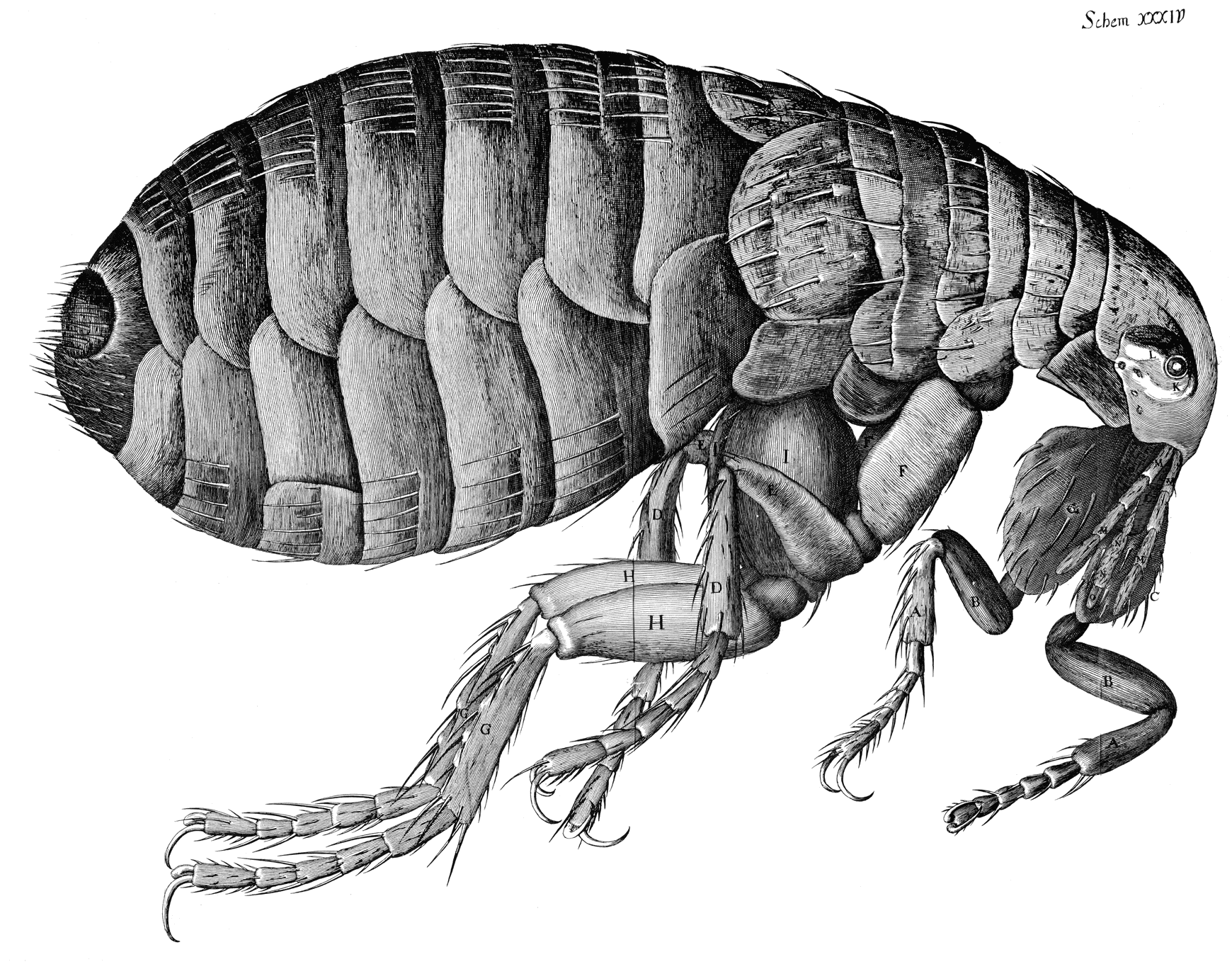

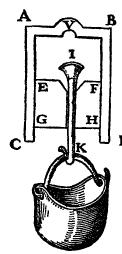

Many of the books we looked at contain beautiful illustrations of instruments and experiments. These nicely capture the experimental natural philosophy.

Adams (1787), 'Essays on the Microscope'

Boyle (1744), 'The Works of the Honourable Robert Boyle in five volumes'

Hooke (1665), 'Micrographia'

Swanenburgh (1616) 'Comfortable Bones, the Skeletons of Adam and Eve'

But we claim that experimental philosophy went beyond natural philosophy. Are there any images that capture its wider application?

Finally, I couldn’t resist adding the burning arm chair, which has special significance for our team: it is at once both a nice image of the shift from speculative to experimental philosophy, and a nod to the local ‘scarfie’ (Otago undergraduate) population of Dunedin. A favourite pastime for scarfies, here in Dunedin, is to burn couches outside their houses!

Burning the proverbial 'Philosopher's Armchair'

We’re looking for an image for our exhibition poster, and we’d like your help. Have you seen an image that captures the spirit of early modern experimental philosophy? We’d love to hear from you. (We’re giving away a one-year subscription to our blog for the reader who provides the best image!)

*The exhibition will be at the Special Collections, Central Library, University of Otago in Dunedin. It will open in early July at the annual conference of the Australasian Association of Philosophy (AAP). So don’t forget to have a look at it, if you are coming to Dunedin in July. For those who cannot come, don’t miss the online version of the exhibition. We’ll be sure to let you know as soon as it is available.

From Experimental Philosophy to Empiricism: 20 Theses for Discussion

Before our recent symposium, we decided to imitate our early modern heroes by preparing a set of queries or articles of inquiry. They are a list of 20 claims that we are sharing with you below. They summarize what we take to be our main claims and findings so far in our study of early modern experimental philosophy and the genesis of empiricism.

After many posts on rather specific points, hopefully our 20 theses will give you an idea of the big picture within which all the topics we blog about fit together, from Baconian natural histories and optical experiments to moral inquiries or long-forgotten historians of philosophy.

Most importantly, we’d love to hear your thoughts! Do you find any of our claims unconvincing, inaccurate, or plainly wrong? Do let us know in the comments!

Is there some important piece of evidence that you’d like to point our attention to? Please get in touch!

Are you working on any of these areas and you’d like to share your thoughts? We’d like to hear from you (our contacts are listed here).

Would you like to know more on some of our 20 claims? Please tell us, we might write a post on that (or see if there’s anything hidden in the archives that may satisfy your curiosity).

Here are our articles, divided into six handy categories:

General

1. The distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy (ESD) provided the most widespread terms of reference for philosophy from the 1660s until Kant.

2. The ESD emerged in England in the late 1650s, and while a practical/speculative distinction in philosophy can be traced back to Aristotle, the ESD cannot be found in the late Renaissance or the early seventeenth century.

3. The main way in which the experimental philosophy was practised from the 1660s until the 1690s was according to the Baconian method of natural history.

4. The Baconian method of natural history fell into serious decline in the 1690s and is all but absent in the eighteenth century. The Baconian method of natural history was superseded by an approach to natural philosophy that emulated Newton’s mathematical experimental philosophy.

Newton

5. The ESD is operative in Newton’s early optical papers.

6. In his early optical papers, Newton’s use of queries represents both a Baconian influence and (conversely) a break with Baconian experimental philosophy.

7. While Newton’s anti-hypothetical stance was typical of Fellows of the early Royal Society and consistent with their methodology, his mathematisation of optics and claims to absolute certainty were not.

8. The development of Newton’s method from 1672 to 1687 appears to display a shift in emphasis from experiment to mathematics.

Scotland

9. Unlike natural philosophy, where a Baconian methodology was supplanted by a Newtonian one, moral philosophers borrowed their methods from both traditions. This is revealed in the range of different approaches to moral philosophy in the Scottish Enlightenment, approaches that were all unified under the banner of experimental philosophy.

10. Two distinctive features of the texts on moral philosophy in the Scottish Enlightenment are: first, the appeal to the experimental method; and second, the explicit rejection of conjectures and unfounded hypotheses.

11. Experimental philosophy provided learned societies (like the Aberdeen Philosophical Society and the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh) with an approach to knowledge that placed an emphasis on the practical outcomes of science.

France

12. The ESD is prominent in the methodological writings of the French philosophes associated with Diderot’s Encyclopédie project, including the writings of Condillac, d’Alembert, Helvétius and Diderot himself.

Germany

13. German philosophers in the first decades of the eighteenth century knew the main works of British experimental philosophers, including Boyle, Hooke, other members of the Royal Society, Locke, Newton, and the Newtonians.

14. Christian Wolff emphasized the importance of experiments and placed limitations on the use of hypotheses. Yet unlike British experimental philosophers, Wolff held that data collection and theory building are simultaneous and interdependent and he stressed the importance of a priori principles for natural philosophy.

15. Most German philosophers between 1770 and 1790 regarded themselves as experimental philosophers (in their terms, “observational philosophers”). They regarded experimental philosophy as a tradition initiated by Bacon, extended to the study of the mind by Locke, and developed by Hume and Reid.

16. Friends and foes of Kantian and post-Kantian philosophies in the 1780s and 1790s saw them as examples of speculative philosophy, in competition with the experimental tradition.

From Experimental Philosophy to Empiricism

17. Kant coined the now-standard epistemological definitions of empiricism and rationalism, but he did not regard them as purely epistemological positions. He saw them as comprehensive philosophical options, with a core rooted in epistemology and philosophy of mind and consequences for natural philosophy, metaphysics, and ethics.

18. Karl Leonhard Reinhold was the first philosopher to outline a schema for the interpretation of early modern philosophy based (a) on the opposition between Lockean empiricism (leading to Humean scepticism) and Leibnizian rationalism, and (b) Kant’s Critical synthesis of empiricism and rationalism.

19. Wilhelm Gottlieb Tennemann was the first historian to craft a detailed, historically accurate, and methodologically sophisticated history of early modern philosophy based on Reinhold’s schema. [Possibly with the exception of Johann Gottlieb Buhle.]

20. Tennemann’s direct and indirect influence is partially responsible for the popularity of the standard narratives of early modern philosophy based on the conflict between empiricism and rationalism.

That’s it for now. Come back next Monday for Gideon Manning‘s comments on the origins of the experimental-speculative distinction.

Lost in translation

Peter Anstey writes…

Sometimes our historiographical categories can so dominate the way we approach the texts of great dead philosophers that we project them onto the texts themselves. Unhappily this is all too common among historians of early modern philosophy who take as their terms of reference the distinction between rationalism and empiricism.

For example, Stephen Priest, in The British Empiricists (2nd ed. 2006, p. 8) claims:

- Although historians of philosophy claim that Kant invented the empiricist/rationalist distinction and retrospectively imposed it on his seventeenth- and eighteenth-century predecessors, this is a historical mistake. The distinction was explicitly drawn using the words “empiricists” and “rationalists” at least as early as 1607, when the British empiricist Francis Bacon (1561–1626) wrote: “Empiricists are like ants; they collect and put to use; but rationalists are like spiders; they spin threads out of themselves” and:

Those who have handled sciences have been either men of experiment or men of dogmas. The men of experiment are like the ant; they only collect and use; the reasoners resemble spiders, who make cobwebs out of their own substance.

[…] Leaving aside the use of the words “rationalism” and “empiricism” (or similar) the distinction between the two kinds of philosophy is as old as philosophy itself. It is true that many rationalist and empiricists do not describe themselves as rationalists or empiricists but that does not matter. Calling oneself “x” is neither necessary nor sufficient for being x.

However, a careful reading of Bacon’s Latin reveals that he is not using the Latin equivalents of ‘empiricists’ and ‘rationalists’, but rather empirici and rationales, terms that have quite different meanings in Bacon. For Bacon, the empirici are those who focus too much on observation and the works of their hands (New Organon, I, 117). Quacks who prescribe chemical remedies without any knowledge of medical theory are commonly called empirici and the term is usually a pejorative in the early seventeenth century (see De augmentis scientiarum, Bk IV, chapter 2). By contrast rationales are those who ‘wrench things various and commonplace from experience… and leave the rest to meditation and intellectual agitation’ (New Organon, I, 62).

Another example of projecting the rationalism/empiricism distinction onto a text is found in the recent English edition of Diderot’s Pensées sur l’interpretation de la nature. Diderot’s work contains a very interesting discussion of philosophical methodology. Article XXIII says,

- Nous avons distingué deux sortes de philosophies, l’expérimentale et la rationnelle.

The translation in the Clinamen Press (1999, p. 44) edition reads:

- We have identified two types of philosophy – one is empirical and the other rationalist.

But Diderot doesn’t contrast empirical with rationalist. Rather the contrast is between experimental philosophy (la philosophie expérimentale) and rational and the context makes it clear that rationnelle here is used to refer to what the English called speculative philosophers. The terminology and the content of Diderot’s discussion makes far more sense when read in the light of the experimental/speculative distinction. Yet this is lost in the English translation.

Having pointed out two examples of reading the traditional historiography into the texts themselves, I should like to end with a note of caution. Those of us who regard the experimental/speculative distinction as having more explanatory value than the traditional post-Kantian terms of reference also need to be aware that we too can fall into the same trap of reading the ESD into the texts under study and not allow the texts to speak for themselves.

Experimental Philosophy and the Origins of Empiricism: Symposium Abstracts

Hello, readers!

Below are the abstracts of the papers that we will discuss at the upcoming symposium on experimental philosophy and the origins of empiricism. The symposium will take place at the University of Otago in Dunedin, NZ, on the 18th and 19th of April and you can find the programme here.

If you would like to attend but have not registered yet, drop an email to Peter. Attendance is free, but we’d like to have an idea of how many people are coming. If you cannot attend, but are interested in some of the papers, let Alberto know. We are happy to circulate them in advance and would love to hear your comments. Also, check this blog in the weeks after the symposium. We will post discussions and commentaries on the papers. We’re looking forward to extend our discussions to the blog. We might also post the video of one of our sessions if we manage to.

Peter Anstey, The Origins of the Experimental-Speculative Distinction

This paper investigates the origins of the distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy (ESP) in the mid-seventeenth century. It argues that there is a significant prehistory to the distinction in the analogous division between operative and speculative philosophy, which is commonly found in late scholastic philosophy and can be traced back via Aquinas to Aristotle. It is argued, however, the ESP is discontinuous with this operative/speculative distinction in a number of important respects. For example, the latter pertains to philosophy in general and not to natural philosophy in particular. Moreover, in the late Renaissance operative philosophy included ethics, politics and oeconomy and not observation and experiment – the things which came to be considered constitutive of the experimental philosophy. It is also argued that Francis Bacon’s mature division of the sciences, which includes a distinction in natural philosophy between the operative and the speculative, is too dissimilar from the ESP to have been an adumbration of this later distinction. No conclusion is drawn as to when exactly the ESP emerged, but a series of important developments that led to its distinctive character are surveyed.

Related posts: Who invented the Experimental Philosophy?

Juan Gomez, The Experimental Method and Moral Philosophy in the Scottish Enlightenment

One of the key aspects, perhaps the most important one, of the enlightenment in Great Britain is the scientifically driven mind set of the intellectuals of the time. This feature, together with the emphasis of the importance of the study of human nature gave rise to the ‘science of man.’ It was characterized by the application of methods used in the study of the whole of nature to inquiries about our own human nature. This view is widely accepted among scholars, who constantly mention that the way of approaching moral philosophy in the eighteenth century was by considering it as much a science as natural philosophy, and therefore the methods of the latter should be applied to the former. Nowhere is this more evident than in the texts on moral philosophy by the Scottish intellectuals. But despite the common acknowledgement of this feature, the specific details and issues of the role of the experimental method within moral philosophy have not been fully explored. In this paper I will explore the salient features of the experimental method that was applied in the Scottish moral philosophy of the enlightenment by examining the texts of a range of intellectuals.

Related posts: Turnbull and the ‘spirit’ of the experimental method; David Fordyce’s advice to students.

Peter Anstey, Jean Le Rond d’Alembert and the Experimental Philosophy

If the experimental/speculative distinction provided the dominant terms of reference for early modern philosophy before Kant, one would expect to find evidence of this in mid-eighteenth-century France amongst the philosophes associated with Diderot’s Encyclopédie project. Jean Le Rond d’Alembert’s ‘Preliminary Discourse’ to the Encyclopedie provides an ideal test case for the status of the ESP in France at this time. This is because it is a methodological work in its own right, and because it sheds light on d’Alembert’s views on experimental philosophy expressed elsewhere as well as the views of others among his contemporaries. By focusing on d’Alembert and his ‘Discourse’ I argue that the ESP was central to the outlook of this philosophe and some of his eminent contemporaries.

Kirsten Walsh, De Gravitatione and Newton’s Mathematical Method

Newton’s manuscript De Gravitatione was first published in 1962, but its date of composition is unknown. Scholars have attempted to date the manuscript, but they have not yet reached a consensus. There have been two main attempts to date De Gravitatione. Hall & Hall (1962) argue for an early date of 1664 to 1668, but no later than 1675. Dobbs (1991) argues for a later date of late-1684 to early-1685. Each side lists handwriting analysis and various conceptual developments as evidence.

In the first part of this paper, I examine the evidence provided by these two attempts. I argue that the evidence presented provides a lower limit of 1668 and an upper limit of 1684. In the second part of this paper, I compare De Gravitatione‘s two-pronged methodology with the mathematical method in Newton’s early optical papers composed between 1672 and 1673. I argue that the two-pronged methodology of De Gravitatione is a more sophisticated version of the mathematical method used in Newton’s early optical papers. Given this new evidence, I conclude that Newton probably composed De Gravitatione after 1673.

Related posts: Newton’s Method in ‘De gravitatione’

Alberto Vanzo, Experimental Philosophy in Eighteenth Century Germany

The history of early modern philosophy is traditionally interpreted in the light of the dichotomy between empiricism and rationalism. Yet this distinction was first developed by Kant and his followers in the late eighteenth century. Many early modern thinkers who are usually categorized as empiricists associated themselves with the research program of experimental philosophy and labelled their opponents speculative philosophers. Did Kant and his followers know the tradition of experimental philosophy and the historical distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy? If so, what prompted them to introduce the historiographical distinction between empiricism and rationalism?

To answer these questions, the first part of the paper focuses on Christian Wolff, the most influential German philosopher of the first half of the eighteenth century. It is argued that Wolff developed his philosophy in a way that was orthogonal to the experimental-speculative distinction. The second part of the paper argues that the distinction experimental-speculative distinction was known and widely used by Kant’s contemporaries from the 1770s to the end of the century. It is concluded that Kant and his followers were well aware of experimental philosophy. Their choice not to focus on the ESD must have been a deliberate one.

Related posts: Experiment and Hypothesis, Theory and Observation: Wolff vs Newton; Tetens on Experimental vs Speculative Philosophy

Alberto Vanzo, Empiricism vs Rationalism: Kant, Reinhold, and Tennemann

Many scholars have criticized histories of early modern philosophy based on the dichotomy of empiricism and rationalism. Among the reasons for their criticism are:

- The epistemological bias: histories of philosophy which give pride of place to the rationalism-empiricism distinction (RED) overestimate the importance of epistemological issues for early modern philosophers.

- The Kantian bias: histories of early modern philosophy that embrace the RED are often biased in favour of Immanuel Kant’s philosophy. They portray Kant as the first author who uncovered the limits of rationalism and empiricism, rejected their mistakes, and incorporated their correct insights within his Critical philosophy.

- The classificatory bias: histories of philosophy based on the RED tend to classify all early modern philosophers prior to Kant into either the empiricist, or the rationalist camps. However, these classifications have proven far from convincing.

After summarizing Kant’s discussions of empiricism and rationalism, the paper argues that Kant did not have the classificatory, Kantian, and epistemological biases. However, he promoted a way of writing histories of philosophy from which those biases would naturally flow. It is argued that those biases can be found in the early Kant-inspired historiography of Karl Leonhard Reinhold and Wilhelm Gottlieb Tennemann.

Related posts: Kant, Empiricism, and Historiographical Biases; Reinhold on Empiricism, Rationalism, and the Philosophy without Nicknames

Thanks to Wordle for the word cloud above.

Locke’s Master-Builders were Experimental Philosophers

Peter Anstey says…

In one of the great statements of philosophical humility the English philosopher John Locke characterised his aims for the Essay concerning Human Understanding (1690) in the following terms:

- The Commonwealth of Learning, is not at this time without Master-Builders, whose mighty Designs, in advancing the Sciences, will leave lasting Monuments to the Admiration of Posterity; But every one must not hope to be a Boyle, or a Sydenham; and in an age that produces such Masters, as the Great – Huygenius, and the incomparable Mr. Newton, with some other of that Strain; ’tis Ambition enough to be employed as an Under-Labourer in clearing Ground a little, and removing some of the Rubbish, that lies in the way to Knowledge (Essay, ‘Epistle to the Reader’).

Locke regarded his project as the work of an under-labourer, sweeping away rubbish so that the ‘big guns’ could continue their work. But what is it that unites Boyle, Sydenham, Huygens and Newton as Master-Builders? It can’t be the fact that they are all British, because Huygens was Dutch. It can’t be the fact that they were all friends of Locke, for when Locke penned these words he almost certainly had not even met Isaac Newton. Nor can it be the fact that they were all eminent natural philosophers, after all, Thomas Sydenham was a physician.

In my book John Locke and Natural Philosophy, I contend that what they had in common was that they all were proponents or practitioners of the new experimental philosophy and that it was this that led Locke to group them together. In the case of Boyle, the situation is straightforward: he was the experimental philosopher par excellence. In the case of Newton, Locke had recently reviewed his Principia and mentions this ‘incomparable book’, endorsing its method in later editions of the Essay itself. Interestingly, in his review Locke focuses on Newton’s arguments against Descartes’ vortex theory of planetary motions, which had come to be regarded as an archetypal form of speculative philosophy.

In the case of Huygens, little is known of his relations with Locke, but he was a promoter of the method of natural history and he remained the leading experimental natural philosopher in the Parisian Académie. In the case of Sydenham, it was his methodology that Locke admired and, especially those features of his method that were characteristic of the experimental philosophy. Here is what Locke says of Sydenham’s method to Thomas Molyneux:

- I hope the age has many who will follow [Sydenham’s] example, and by the way of accurate practical observation, as he has so happily begun, enlarge the history of diseases, and improve the art of physick, and not by speculative hypotheses fill the world with useless, tho’ pleasing visions (1 Nov. 1692, Correspondence, 4, p. 563).

Note the references to ‘accurate practical observation’, the decrying of ‘speculative hypotheses’ and the endorsement of the natural ‘history of diseases’ – all leading doctrines of the experimental philosophy in the late seventeenth century. So, even though Sydenham was a physician, he could still practise medicine according to the new method of the experimental philosophy. In fact, many in Locke’s day regarded natural philosophy and medicine as forming a seamless whole in so far as they shared a common method. It should be hardly surprising to find that Locke held this view, for he too was a physician.

If it is this common methodology that unites Locke’s four heroes then we are entitled to say ‘Locke’s Master-Builders were experimental philosophers’. I challenge readers to come up with a better explanation of Locke’s choice of these four Master-Builders.

Galileo and Experimental Philosophy

Greg Dawes writes…

In a recent conference paper I have argued that in some key respects Galileo’s natural philosophy anticipates the experimental philosophy of the later seventeenth century. I am not claiming that Galileo uses the term “experimental philosophy.” Nor do I claim that he makes any distinction comparable to that between experimental and speculative natural philosophy. His Italian followers in the Accademia del Cimento would later do so, but he does not. Nonetheless, the way in which Galileo undertakes natural philosophy displays at least two of the features that Peter Anstey and his collaborators have argued are characteristic of experimental philosophy.

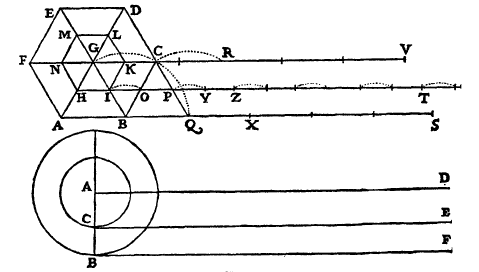

Galileo's sketch of a device to demonstrate the power of a vacuum.

The first of these has to do with the role of experiment. Much of the twentieth-century debate centred on whether Galileo actually performed the experiments about which he writes. But the more important question has to do with the role of experiments in Galileo’s thought. Like his Aristotelian predecessors, Galileo seeks to construct a demonstrative natural philosophy: one in which the conclusions follow with certainty from the premises. But unlike the Aristotelian, he relies on geometrical proofs. Like any mathematical proofs, these can be elaborated in an a priori fashion, without any reference to experience. But whether a particular proof applies to the world of experience – or, better still, whether it accurately describes the structure of the world – can only be ascertained experimentally. It is experiment which tells us which geometrical proof is to be used, even if the geometrical proof itself can be developed independently of experience. (I am relying here on the work of Martha Féher, Peter Machamer, and others.)

Perhaps more importantly, Stephen Gaukroger has argued that experimentation shaped the very way in which Galileo’s physical theories are framed and formulated. Alexander Koyré and others have argued that the laws of Galilean physics are “abstract” laws which refer to an ideal reality. It is true, of course, that in setting aside “impediments” (impedimenti), such as the resistance of the air, Galileo’s proofs do not refer to the world of everyday experience. But it is unhelpful to think of them as an idealisations of, or abstractions from, experienced reality. There is an experienced reality to which they conform. It may not be that of everyday experience, but it is that of carefully controlled physical experiments. It follows that in Galileo’s work, the task of natural philosophy is being rethought. It is no longer the study of reality as revealed to everyday observation; it is the study of that reality revealed in experimental situations.

The second way in which Galileo’s natural philosophy anticipates the later experimental philosophy is in its comparative lack of interest in the mechanisms thought to underlie phenomena. It is not that Galileo was a positivist in our modern sense. There are passages in which he engages in speculation regarding matter theory and on these occasions he favours a corpuscularian view. But such speculations are, as Salviati says in the Two New Sciences, a mere “digression.” Galileo does not consider that his new science requires them. Indeed his work on motion is almost entirely a kinematics – as he freely admits, it says nothing about the causes of motion – but Galileo does not consider it any less significant as a result.

Galileo's solution of the "rota Aristotelis" paradox, demonstrating that a body could be composed of an infinite number of unquantifiable atoms.

This should not be interpreted as a general lack of interest in causation, as Stillman Drake suggests. Galileo shares the ancient desire cognoscere rerum causas (to know the causes of things). But the causal properties Galileo seeks are different from those sought by his predecessors. His causes are the mathematically describable properties of the objects whose behaviour is being explained, properties that no Aristotelian would regard as essential. (Even his atoms are more akin to mathematical points than physical objects.) It is, once again, experimentation that allows us to pick up which of those mathematically describable properties are generally operative and therefore the proper subject of a science. It is this move that allows Galileo, as it would later allow Newton, to be content with a causal account that remains on the level of phenomena, rather than speculating about a realm inaccessible to observation.

In an early dialogue, Galileo has two rustics (contadini) speculating about the new star of 1605. One of them advises his companion to listen to the mathematicians rather than the philosophers, for they can measure the sky the way he himself can measure a field. It doesn’t matter of what material the heavens are made. “If the sky were made of polenta,” he says, “couldn’t they still see it alright?” This is surely something new in the history of natural philosophy.

Postscript:

While I would still defend the individual claims contained here, my continued study of Galileo has made me increasingly cautious about the usefulness of a distinction between experimental and speculative natural philosophy. It is certainly the case that many late seventeenth-century thinkers made such a distinction, but is it a useful one for us to make? I’m not confident that it is.

Experiment certainly played an important role in Galileo’s work, although precisely what that role was continues to be contested. And it is true that Galileo has little interest in speculating about the underlying structure of the world: even if, as he writes, the sky were made of polenta, the mathematicians could still measure it. The problem is that the classical, mathematical tradition out of which he comes — that of astronomy, statics, optics, and (after Galileo) the study of local motion — cannot be helpfully characterized as either experimental or speculative. It certainly uses experiment, but it also reasons a priori, in ways that seem independent of experience.

So perhaps it would be better to have a threefold classification of early modern scientific traditions. (A classification of this kind is suggested by Casper Hakfoort in the last chapter of his Optics in the Age of Euler.) A first tradition would be that of matter theory, which is inevitably speculative insofar as it deals with matters not accessible to direct observation. (This is the realm of Newton’s “hypotheses.”) Corpuscularian proposals would fall into this category, as would Descartes’s vortex theory. A second tradition would be that of experimental natural philosophy, which regarded the results of experiment as themselves significant forms of knowledge, whether or not they could be connected with an underlying theory of the nature of matter. Finally, there is the mathematical tradition that Galileo transformed, so successfully, by producing a mathematical account of local motion.

Individual natural philosophers could engage in all three kinds of activities, but will differ according to the emphasis they place on one or other of them. So although Galileo certainly engaged in experiments, his emphasis was on the kind of reasoning characteristic of the mathematical tradition. It is this form of reasoning, I have come to believe, that cannot be easily fitted into the experimental-speculative scheme.