The Prehistory of Empiricism

Alberto Vanzo writes…

As some of you will know, I have claimed for a while that the distinction between empiricism and rationalism was first introduced by Kant in the Critique of Pure Reason. However, a quick search on Google Books reveals that there were many occurrences of “empiricism” and “rationalism” before Kant was even born. What is new about Kant’s use of these terms?

In this post I will survey early modern uses of “empiricism” and its cognates, “empiric” and “empirical”. I will argue that Kant’s new use of “empiricism” reflects a shift from the historical tradition of experimental philosophy to a new set of concerns.

Medical empiricism

Early modern authors often used “empiricism” and its cognates in medical contexts. Empirical physicians were said to depend “on experience without knowledge or art”. They did not have a good reputation. Shakespeare was expressing a common view when he wrote in All’s Well that Ends Well: “We must not corrupt our hope, To prostitute our past-cure malladie To empiricks”.

However, some defended empirical physicians. For instance, according to Johann Georg Zimmermann, the ancient physician Serapion of Alexandria was a good empiric. Why? Because he followed the method of experimental philosophy. He relied on experience and rejected idle hypotheses:

- Serapion and his followers rejected the inquiries of hidden causes and stuck to the visible ones […] So one can see that the founder of the sect of empirics had the noble purpose to band the love of hypotheses and useless quarrels from the medical art.

Political empiricism

Tetens wrote in 1777: “It has been asked in politics whether [politicians] should derive their maxims from the way the world goes, or whether they should derive them from rational insight.” Those who chose the first alternative were empirical politicians. Like empirical physicians, they were usually the target of criticism. Several writers throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth century agreed that true politicians could not be “blind empirics”.

Who opposed empirical politicians? It was the dogmatic or — as a review from 1797 called them, speculative politicians. Speculative politicians relied on “philosophical hypotheses and unilateral [i.e., insufficient] observations”, from which they rashly derived general conclusions. Once again, empirical politicians and their adversaries are implicitly identified with experimental and speculative philosophers.

Empirical people

The term “empiric” was also used in a general sense to refer to people who “owe their cognition to the senses” and “steer their actions on the basis of experience“. Leibniz famously said that we are empirics in three quarters of our actions. Bacon called empirics those who perform experiment after experiment without ever reflecting on the causes and principles that govern what they experience.

At least two of Kant’s German predecessors, Baumgarten and Mayer, coined disciplines called “empiric” that deal with the origin of our cognitions from experience or introspection. Additionally, two German historians identified an “empirical philosophy” that they contrasted with “scientific philosophy”.

Kant: what’s new in his usage?

Kant built on these linguistic uses when he introduced a new notion of empiricism:

- Like the authors referred to by some historians, Kant’s empiricists are philosophers.

- Like empirical physicians, empirical politicians, and empirical people, Kant’s empiricists rely entirely on experience.

However, Kant’s empiricism is not a generic reliance on experience, nor is it primarily related to the rejection of hypotheses and speculative reasonings. Kant’s empiricists advocate specific epistemological views (taking “epistemology” in a broad sense), that is, views on the origins and foundations of our knowledge. They deny that we can have any substantive a priori knowledge and they claim that all of our concepts derive from experience.

What is new in Kant’s notion of empiricism is the shift from a generic reference to experience and to the methodological issues that were distinctive of early modern x-phi, to broadly epistemological issues. To be sure, Kant was not concerned with epistemology for its own sake. He aimed to answer ontological and moral questions. Nevertheless, the epistemological issues that Kant’s new notion of empiricism focuses on are the issues that post-Kantian histories of philosophy, based on the dichotomy of empiricism and rationalism, would place at the centre of their narratives.

Do you think this is persuasive? I am collecting early modern uses of “empiricism” and “rationalism”, so if you know some interesting occurrence, please let me know. Also, if you are familiar with methods for performing quantitative analyses of early modern corpora, could you get in touch? I would appreciate your advice.

The Academy of Lagado and the usefulness of science

Juan Gomez writes…

In our recent book exhibition Experimental Philosophy: Old and New, there is a cabinet on literature, where we show how the experimental philosophy was depicted in the works of the literary figures of Voltaire, Alexander Pope, and Jonathan Swift. In this post I want to comment in a little bit more detail on Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels.

In the first part of the third voyage, Captain Lemuel Gulliver travels to the island of Laputa. As the exhibition caption for Swift’s book says, this flying island is a satirical representation of the Royal Society, criticizing how detached their members were from the real world, being too concerned with their science. To begin with, Laputa is a flying island, symbolizing the separation between the world of science and the world of ordinary people, the real world. Swift’s description of the inhabitants of the island stresses this point:

- It seems, the Minds of these People are so taken up with intense Speculations, that they neither can speak, or attend to the Discourses of others, without being rouzed by some external Taction upon the Organs of speech and Hearing […]

Not only did they have a hard time communicating with each other, but they could not even understand things that were not presented in a mathematical or scientific manner. Gulliver relates that all their food was prepared in the form of geometrical figures; the mutton was cut in the form of an equilateral triangle, the beef in rhomboids, and the bread in cones and cylinders.

Though the island is a representation of both British science and the Court, the Academy of Lagado is a clear satire of the Royal Society. Swift’s description of the Academy questions the usefulness of the experiments carried out by the society. He mentions all sort of experiments that sound ridiculous: extracting sunbeams out of a cucumber, reducing human excrement to its original food, turning limestone into gunpowder, building houses by starting with the roof, and the list goes on. Some of these experiments might not sound that ridiculous to us, but they sure would to the eighteenth-century reader.

Swift goes on with his criticism of members of the Royal Society, and even makes a reference to the Newton-Leibniz priority dispute over the calculus. The point I want to direct our attention to is the underlying criticism that questions the usefulness of the experiments of the Royal Society. Marjorie Nicholson and Nora Mohler wrote an excellent paper on Swift and science, where they show that the descriptions given by Gulliver were all inspired by actual experiments published in the Philosophical Transactions. Though Swift exaggerates and mixes some of the actual experiments, it is clear that his aim was to question their use and value for society.

This raises an interesting issue regarding Philosophical Societies and their commitment to the experimental method. Inspired by Bacon’s New Atlantis, the scientific academies adopted the experimental method in part because it was aimed at the improvement of society, unlike pure speculation. Swift’s criticisms highlight a possible tension between the aim of improving society and the focus on experiments. I think Swift is being too harsh in his satire, and some of the experiments he exaggerates and tinkers with actually had practical application to ordinary people. Not only do we see this with some of the experiments carried out by the Royal Society, but the Scottish philosophical societies provide an even clearer example of the applications of their experiments for the improvement of society.

Swift was just too impatient to wait longer for the results of the experiments he saw as ridiculous. Nevertheless, we can still question the usefulness of the experiments carried out by the experimental philosophers. As Peter Anstey commented on a previous post, after the last decade of the seventeenth-century experimental philosophers preferred Newton’s “mathematical natural philosophical method” to the Baconian method of natural histories. This change can lead to the worry that experimental philosophers would end up focusing excessively on the mathematical theory, thus detaching from the more practical side of their experiments.

I do not think this was the case. What the shift in method caused was a change from the collection of facts to the deduction of principles from facts and observation. The preference for the Newtonian method doesn’t require the neglect of observation. This being the case, the tension raised by Swift’s satire should not be a worry, since it still allows experimental philosophy to be directed towards the improvement of mankind. In fact, Swift’s criticism aimed towards the uselessness of science is exactly what experimental philosophers argued was one of the downfalls of speculative philosophy: it was detached from the real world.

Could it be the case the experimental philosophers were guilty of the very same thing they thought was a very negative aspect of their speculative counterparts? As I have mentioned here I don’t think this is the case; but I’m interested in the thoughts of our readers regarding this issue.

Thomas Sydenham, the experimental physician

Peter Anstey writes…

The London physician Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689) is regarded today as one of the greatest physicians of the seventeenth century. He is even claimed to have had an influence on the philosophy of John Locke. But what exactly is the basis of Sydenham’s reputation?

A careful study of the appearance of Sydenham’s name in the medical writings of the latter decades of the seventeenth century and the correspondence of his friends and associates reveals that during his professional years he faced constant opposition and criticism. Henry Oldenburg, Secretary of the Royal Society, said of him in a letter to Robert Boyle (24 December 1667): ‘with so mean and un-moral a Spirit I can not well associate’. Sydenham was never to become a Fellow of the Royal Society or of the College of Physicians.

However, his posthumous reputation is markedly different. After his death, Sydenham was praised for three things: his commitment to natural histories of disease; his decrying of hypotheses and speculation; and his Hippocratic emphasis on observation. Interestingly, these are the hallmarks of the experimental philosophy. Witness, for example, what Locke says of him in a letter to Thomas Molyneux of 1 November 1692:

- I hope the age has many who will follow his example, and by the way of accurate practical observation, as he has so happily begun, enlarge the history of diseases, and improve the art of physick, and not by speculative hypotheses fill the world with useless, tho’ pleasing visions.

By the early eighteenth century Sydenham’s name could hardly be mentioned without effusive praise, such as that found in George Sewell’s ode to Sir Richard Blackmore:

- Too long have we deplor’d the Physick State, …

Then vain Hypothesis, the Charm of Youth,

Oppose’d her Idol Altars to the Truth: …

Sydenham, at length, a mighty Genius, came,

Who founded Medicine on a nobler Frame,

Who studied Nature thro’, and Nature’s Laws,

Nor blindly puzzled for the peccant Cause.

Father of Physick He—Immortal Name!

Who leaves the Grecian [Hippocrates] but a second Fame:

Sing forth, ye Muses, in sublimer Strains

A new Hippocrates in Britain reigns.

These comments are of the most general nature. There is nothing about the actual content of Sydenham’s medical theories or therapeutics, which were so harshly criticized while he was alive. It is all about his methodology and it is cashed out in terms of the experimental philosophy.

Thomas Sydenham, by a remarkable change in fortunes, came to be regarded as the archetypal experimental physician largely thanks to his posthumous promoters such as John Locke. Sydenham, for better or for worse, was the experimental physician that the promoters of the experimental philosophy had to have.

A year on…

Hello, Readers!

One year ago today, we published our first post to present our research project to the world. We were new to blogging and we weren’t quite sure how effective it would be. After twelve months and 58 posts, there is no trace of those initial doubts. Forcing ourselves to publish a new piece on our work in progress (nearly) each week has been a good exercise. It has helped us to be productive, to keep each other abreast of each other’s research, and to grow as a team. Most of all, it has been great to receive the attention and feedback of our readers. Today we’d like to thank you for being on board, to look back at where we’ve come from, and to ask for a bit more of your helpful advice.

First of all, we are most grateful for our readers’ emails, comments and posts on our project elsewhere on the Net. You have taught us about the notion of experience in early modern Aristotelianism (1 to 8), outlined the evidence for Hume’s knowledge of Berkeley better than we possibly could, expanded on our reflections on the usefulness or uselessness of the notion of empiricism, alerted us to many sources that we had not taken into account, and provided plenty of other input that helped shaping the directions of our research. We may not have succeeded to persuade you all that ESP is best yet (it is just a matter of time), but we’re learning from your objections. Keep them coming! As you will have guessed, we are all working on research projects that are related to the topics of our posts. It’s helpful to get an early idea of the weak points and potential criticisms of the arguments we’re trying to articulate.

We are especially grateful to the many colleagues whose guest posts broadened and deepened our research on a number of fronts. They taught us about Galileo, De Volder, Sturm, seventeenth-century Dutch physicians, experiment and culture in the historiography of philosophy, in addition to providing critical discussions of many of our own ideas. Stay tuned for more stimulating guest-posts!

For our part, here’s a summary of our first year of blogging:

The Big Picture

We claimed that it’s much better to interpret early modern authors as early modern experimental philosophers than as empiricists. For the details, you can read our 20 theses, tour through our images of experimental philosophy, or head towards these posts:

- Experimental Philosophy and the Origins of Empiricism

- Is x-phi old hat?

- On the Proliferation of Empiricisms

- Lost in translation

- Early modern x-phi:-a genre free zone

Seventeenth Century Britain, plus a new find

In addition to providing the big picture in the above posts, Peter blogged on the origins of x-phi and its impact on seventeenth-century natural philosophy:

- Who invented the Experimental Philosophy?

- Locke’s Master-Builders were Experimental Philosophers

- Two Forms of Natural History

- Baconian versus Newtonian experimental philosophy

- A New Hume Find (Hume’s copy of Berkeley’s Theory of Vision turned up at our uni!)

Newton’s Experimental Philosophy

Moving towards the eighteenth century, Kirsten has explored the new form of the experimental philosophy that took shape in Newton’s mathematical method and its impact on his natural philosophy, especially his optics:

- Should we call Newton a ‘Structural Realist’?

- Newton’s Early Queries are not Hypotheses

- Newton’s ‘Crucial Experiment’

- Newton on Certainty

- Does Newton feign an hypothesis?

X-phi in Eighteenth Century Scotland: Ethics and Aesthetics

Juan has traced the presence of experimental philosophy in Scottish philosophy throughout the eighteenth century, including Turnbull, Fordyce, Reid, and the Edinburgh Philosophical Society. He has focused especially on the experimental method in ethics and aesthetics:

- Experimenting with taste and the rules of art

- Paintings as Experiments in Natural and Moral Philosophy

- Turnbull’s Treatise on Ancient Painting and the Experimental/Speculative Distinction

- Experimental Method in Moral Philosophy

German Thinkers from X-Phi to Empiricism

Alberto has looked at the influence of x-phi in Germany, especially on Leibniz, Wolff, Tetens, and Kant’s contemporaries. He then explored the development of the traditional narrative of early modern philosophy based on the distinction between empiricism an rationalism in Kant, Reinhold, and Tennemann.

For those readers who have followed us from the early days, we hope that a coherent narrative has emerged. We’d love to hear if you think that we’re up to something interesting or that we’re going off track. What better way to celebrate our anniversary than to give us some more feedback! Also, please do let us know if you have any suggestions on topics to study and directions in which we could pursue our research. You can reach us via email, Facebook, and Twitter. As always, you can keep updated via the mailing list or the RSS feed. We still have much to study and to blog about. Thanks for coming along, and we hope you’ll enjoy our future posts.

A new Hume find

Peter Anstey writes…

While the ‘Experimental Philosophy: Old and New’ exhibition was under construction, the Special Collections Librarian at Otago, Dr Donald Kerr, happened to notice that the copy of George Berkeley’s An Essay Towards a New Theory of Vision (2nd edn, 1709) that we were about to display, had the bookplate of David Hume Esquire. It has long been known that this book was in the library of the philosopher David Hume’s nephew Baron David Hume, but until now its whereabouts have been unknown. We are very pleased to announce, therefore, that it is in the Hewitson Library of Knox College at the University of Otago, New Zealand (for full bibliographic details see the online exhibition).

The question naturally arises: did the book belong to the philosopher or the Baron? What complicates matters is that David Hume the philosopher left his library to his nephew of the same name and that the latter also used a David Hume bookplate.

Now the David Hume bookplate exists in two states, A and B. They are easily distinguished because State A has a more elongated calligraphic hood on the second stem of the letter ‘H’ than that of State B. Brian Hillyard and David Fate Norton have pointed out (The Book Collector, 40 [1991], 539–45) that all of the thirteen items that they have examined with State A are on laid paper and are in books that predate the death of David Hume the philosopher. This is not the case for books bearing the State B bookplate. They propose the plausible hypothesis that all books bearing the bookplate in State A belonged to Hume the philosopher. Happily, we can report that the bookplate that here at Otago is State A on laid paper. It is almost certain, therefore, that this copy of George Berkeley’s New Theory of Vision belonged to the philosopher David Hume.

The provenance of the book provides important additional evidence that Hume was familiar with Berkeley’s writings, something that was famously denied by the historian of philosophy Richard Popkin in 1959. Popkin claimed that ‘there is no actual evidence that Hume was seriously concerned about Berkeley’s views’. He was subsequently proven wrong and retracted his claim. However, until now there has been no concrete evidence that Hume owned a copy of a work by Berkeley, let alone one as important as the New Theory of Vision.

This volume came into the possession of the Hewitson Library in 1948. Its title page bears a stamp from the ‘Presbyterian Church of Otago & Southland Theological Library, Dunedin’. So far attempts to ascertain which other books were in this theological library and when and how it arrived in New Zealand have proven fruitless. (Though the copy of William Whiston’s A New Theory of the Earth, 1722 on display bears the same stamp.) If any reader can supply further leads on these matters we would be most grateful. Meanwhile please take time to examine the images of the bookplate and title page, which are included in our online exhibition available here.

Experimental Philosophy: Old and New

Over the last few months, we have been working with Dr Donald Kerr, the Special Collections Librarian at the University of Otago, to prepare a rare book exhibition on the history of experimental philosophy. We have brought together classic works of the past and cutting-edge books of the present, to illustrate the theme of experimental philosophy as it was understood and practised 350 years ago and as it is understood today.

- Our exhibition, ‘Experimental Philosophy: Old and New’, was launched a few weeks ago, to coincide with the annual conference of the Australasian Association of Philosophy (AAP). It will run until 23 September 2011, so if you are coming to Dunedin, be sure to stop by and see it.

For those who cannot come to Dunedin, we are thrilled to announce the launch of the online version of our exhibition. Notable items on display include a second edition of Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1713), Francis Bacon’s Of the Advancement Learning (1640), poet Abraham Cowley’s ‘A Proposition for the Advancement of Experimental Philosophy’ (1668), and an exciting new discovery* concerning the philosopher David Hume!

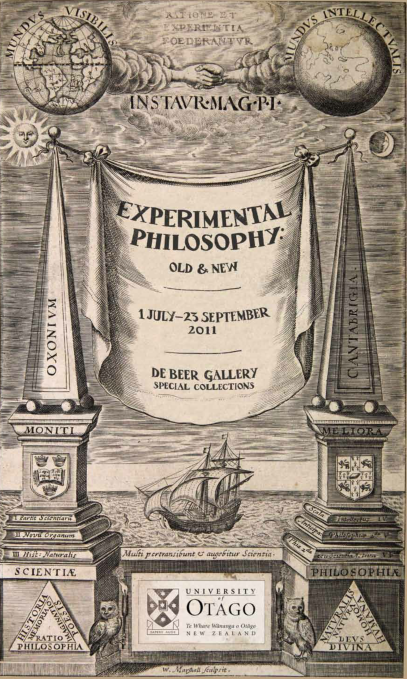

A couple of months ago, I requested your help: we needed an image for our exhibition poster. We received some excellent feedback – so thank you everyone! We eventually settled on a modified version of the frontispiece to 1640 translation of Bacon’s ‘De Augmentis Scientiarum’.

We hope you enjoy our exhibition!

* On Monday Peter Anstey will tell us all about this new discovery regarding Hume.

Experiment, Culture, and the History of Philosophy

One tremendous change over the past 27 years, which makes this redux not simply a repetition, has been the appearance, and reappearance, of experimental philosophy: that is, the emergence of experimental philosophy as a defining feature of the non-historical wing of the discipline, as well as a crucial focus of study (thanks in no small part to the work of the Otago group) for scholars studying the history of early modern philosophy.

A question of central methodological importance for the historian of philosophy concerns the appropriate relationship between the aspects of philosophy’s past that a scholar takes on, on the one hand, and on the other the current agenda of non-historical philosophy. Recently, in the results of a query launched by Mark Lance at the NewAPPS blog, my own deep worry about the state of the discipline was confirmed: a good many non-historian philosophers believe that, at the end of the day, history-of-philosophy scholarship should make itself relevant to the cluster of questions currently being investigated in philosophy. I could not disagree more strongly. To riff on John F. Kennedy’s famous line, I believe that we should not be asking what the history of philosophy can do for us, but rather what we can do for the history of philosophy. That is, we should be attempting to do justice to past thinkers by carefully reconstructing their own world of concerns. In doing so, we shall often have to move beyond the boundaries of what we consider philosophy (and even of what they considered philosophy).

I have argued in many fora that we should respect the historical usage of the term ‘philosophy’. Some have objected that it is a semantic issue –as in, a mere semantic issue– what might have been called by a certain name in another era. What is important, they say, is whether the activity so-called in fact has any continuity with what we are doing when we do philosophy. To some today, the discontinuity seems most evident when we consider early modern experimental philosophy. There simply is no meaningful sense, they maintain, in which we can think of meteorology as a proper part of philosophy, even if this is how it was conceived in the history of natural philosophy from Aristotle through (at least) Boyle.

We might suppose that this discontinuity is bridged to some extent by the recent appearance of an activity going by the name of ‘experimental philosophy’, but of course the scope of ‘experimental’ was very different for, e.g., Margaret Cavendish than for Joshua Knobe. Nonetheless, it is certainly worthwhile to reflect on what the 17th- and 21st-century versions of experimental philosophy share, and also on what they might someday share. For now, the new experimental philosophy sees itself as having common cause principally with experimental psychology. As some philosophers sympathetic to x-phi have argued, however, the concept of ‘experiment’ could be extended much further than has been done so far. Jesse Prinz, in particular, has suggested that ‘experiment’ could be understood broadly to include what we think of as ‘experience’: thereby reuniting it with its lexical ancestor, and also reconciling with the intuitions that x-phi initially came out against.

If experiment is (re-)broadened to include experience, then willy-nilly we arrive in a situation for philosophy in which, in effect, any source of information may be deemed of interest. Such a situation, I think, is one in which history-of-philosophy scholarship could thrive. It is one in which, moreover, this branch of scholarship would find common cause with historical anthropology. It might even open itself up to non-textual sources of information (e.g., instrument design, seed collections). The text would be dethroned as the exclusive source of information about what was motivating thinkers to come up with the ideas they had.

For a long time it has seemed unnecessary to historians of philosophy to move beyond texts, since philosophy is about ideas, and where else but in texts are ideas encoded? Certainly, texts are a useful source of ideas from the past, but seed collections and instrument design are also, so to speak, fossils of past intentions, and there is no reason why they should not complement texts of philosophy, just as the layout of graves complements hieroglyphic texts in an Egyptologist’s effort to reconstruct ancient Egyptian ideas about the afterlife.

But we tend to think of an Egyptologist’s work as having to do with culture, while we do not, today, think of historians of philosophy as specialists in culture at all. Historians of philosophy are supposed to be engaging with more-or-less timeless ideas, which are not supposed to be bound by the parameters of the culture inhabited by the thinker who had them. But let’s be serious. Is, say, Leibniz’s account of the fate of the soul of a dog after death (that is, shrinking down into a microscopic organic body and floating around in the air and in the scum of ponds for all eternity) really any more viable a candidate for the true theory of life after death than the account offered in The Egyptian Book of the Dead? I don’t believe so, and when I read Leibniz’s account it is not because I am considering adopting this account myself. It is because I am interested in the range of ways people in different times and places have conceptualized the irresolvable problem of the fate of the soul. I specialize in 17th-century Christian European approaches to this mystery, but I could just as easily have been an Egyptologist.

To acknowledge that we are studying culture –not all culture, but a particular manifestation of a certain culture: the European educated elite, which leaves its traces in texts, but not only in texts– is to make a move that is exactly parallel to the one practitioners of non-historical experimental philosophy are currently making relative to the discipline that houses them. Current x-phi is putting philosophy back into culture by empirically studying the culture-bound nature of intuitions, rather than resting content with the intuitions of self-appointed experts in intuition-having. This is a welcome development, but I believe it must be seen as just one small part of a broader project of re-embedding philosophy in culture, and I believe historians of philosophy have a particularly important role to play in this project. Philosophy in history is philosophy in culture.

Even if Boyle and Cavendish meant something different by ‘experimental philosophy’ than Knobe and Nichols do, to take an interest in Boyle and Cavendish’s conception of philosophy as extending to experimental science is to contribute in a specialized way, I believe, to the overall aim of current x-phi, which is to study how people in different times and places actually think. In pursuing this aim, current x-phi practitioners have found common cause with experimental psychologists. The parallel interdisciplinary move for the historian of philosophy should be one that brings us closer to the work of historical anthropologists.

Leibniz: An Experimental Philosopher?

Alberto Vanzo writes…

In an essay that he published anonymously, Newton used the distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy to attack Leibniz. Newton wrote: “The Philosophy which Mr. Newton in his Principles and Optiques has pursued is Experimental.” Newton went on claiming that Leibniz, instead, “is taken up with Hypotheses, and propounds them, not to be examined by experiments, but to be believed without Examination.”

Leibniz did not accept being classed as a speculative armchair philosopher. He retorted: “I am strongly in favour of the experimental philosophy, but M. Newton is departing very far from it”.

In this post, I will discuss what Leibniz’s professed sympathy for experimental philosophy amounts to. Was Newton right in depicting him as a foe of experimental philosophy?

To answer this question, let us consider four typical features of early modern experimental philosophers:

- self-descriptions: experimental philosophers typically called themselves such. At the very least, they professed their sympathy towards experimental philosophy.

- friends and foes: experimental philosophers saw themselves as part of a tradition whose “patriarch” was Bacon and whose sworn enemy was Cartesian natural philosophy.

- method:experimental philosophers put forward a two-stage model of natural philosophical inquiry: first, collect data by means of experiments and observations; second, build theories on the basis of them. In general, experimental philosophers emphasized the a posteriori origins of our knowledge of nature and they were wary of a priori reasonings.

- rhetoric: in the jargon of experimental philosophers, the terms “experiments” and “observations” are good, “hypotheses” and “speculations” are bad. They were often described as fictions, romances, or castles in the air.

Did Leibniz have the four typical features of experimental philosophers?

First, he declared his sympathy for experimental philosophy in passage quoted at the beginning of this post.

Second, Leibniz had the same friends and foes of experimental philosophers. He praised Bacon for ably introducing “the art of experimenting”. Speaking of Robert Boyle’s air pump experiments, he called him “the highest of men”. He also criticized Descartes in the same terms as British philosophers:

- if Descartes had relied less on his imaginary hypotheses and had been more attached to experience, I believe that his physics would have been worth following […] (Letter to C. Philipp, 1679)

Third, the natural-philosophical method of the mature Leibniz displays many affinities with the method of experimental philosophers. To know nature, a “catalogue of experiments is to be compiled” [source]. We must write Baconian natural histories. Then we should “infer a maximum from experience before giving ourselves a freer way to hypotheses” (letter to P.A. Michelotti, 1715). This sounds like the two-stage method that experimental philosophers advocated: first, collect data; second, theorize on the basis of the data.

Fourth, Leibniz embraces the rhetoric of experimental philosophers, but only in part. He places great importance on experiments and observations. However, he does not criticize hypotheses, speculations, or demonstrative reasonings from first principles as such. This is because demonstrative, a priori reasonings play an important role in Leibniz’s natural philosophy.

Leibniz thinks that we can prove some general truths about the natural world a priori: for instance, the non-existence of atoms and the law of equality of cause and effect. More importantly, a priori reasonings are necessary to justify our inductive practices.

When experimental natural philosophers make inductions, they presuppose the truth of certain principles, like the principle of the uniformity of nature: “if the cause is the same or similar in all cases, the effect will be the same or similar in all”. Why should we take this and similar principles to be true? Leibniz notes:

- [I]f these helping propositions, too, were derived from induction, they would need new helping propositions, and so on to infinity, and moral certainty would never be attained. [source]

There is the danger of an infinite regress. Leibniz avoided it by claiming that the assumption of the uniformity of nature is warranted by a priori arguments. These prove that the world God created obeys to simple and uniform natural laws.

In conclusion, Leibniz really was, as he wrote, “strongly in favour of the experimental philosophy”. However, he aimed to combine it with a set of a priori, speculative reasonings. These enable us to prove some truths on the constitution of the natural world and justify our inductive practices. Leibniz’s reflections are best seen not as examples of experimental or speculative natural philosophy, but as eclectic attempts to combine the best features of both approaches. In his own words, Leibniz intended “to unite in a happy wedding theoreticians and observers so as to improve on incomplete and particular elements of knowledge” (Grundriss eines Bedenckens […], 1669-1670).

Experimenting with taste and the rules of art

Juan Gomez writes…

In 1958 Ralph Cohen published a paper titled David Hume’s Experimental Method and the Theory of Taste, where he argues that the main contribution of Hume’s essay Of the Standard of Taste (OST) was his “insistence on method, on the introduction of fact and experience to the problem of taste.” I agree with Cohen, but I think his overall interpretation of the essay on taste still falls short of giving a proper account of Hume’s theory of taste. I’d like to build on Cohen’s statement and support it with the help of the framework we are proposing in this project, where Early Modern Experimental Philosophy plays a prominent role.

Hume’s essay on taste begins with a description of the paradox of taste: It is obvious that taste varies among individuals, but it is also obvious that some judgments of taste are universally agreed upon (Hume’s example is that everyone admits that John Milton is a better writer than John Ogilby). Hume relies on the experimental method to solve the paradox. From the initial paragraphs of the essay we can see that Hume is calling for an approach to the appreciation of art works that resembles the experimental method of natural philosophy. If we are to solve the problem of taste, we need to focus on particular instances, and from them we can deduce the ‘rules of composition’ or ‘rules of art.’ This is achieved the same way natural philosophy observes the phenomena to deduce the laws of nature. The main reason for this focus on particular over the general is that Hume thinks that in matters of taste, as well as in morality founded on sentiment, “The difference among men is really greater than at first sight appear.” Although everyone approves of justice and prudence in general, when it comes to particular instances we find that “this seeming unanimity vanishes.”

The objects we appreciate as works of art, according to Hume, possess qualities that “are calculated to please, and others to displease.” The essay on taste applies the experimental method to particular experiences with artworks, and after a number of these experiences we can identify those qualities which comprise the rules of art:

- “It is evident, that none of the rules of composition are fixed by reasonings a priori, or can be esteemed abstract conclusions of the understanding, from comparing those habitudes and relations of ideas, which are eternal and immutable. Their foundation is the same with that of all the practical sciences, experience; nor are they anything but general observations, concerning what has been universally found to please in all countries and in all ages.” (OST, 210)

We need to approach matters of taste the same way we approach matters of natural philosophy: by focusing on the particular phenomena, which in this case are our interactions with works of art. Hume’s essay on taste works as a guide for the appreciation of art. It is not, as most of the scholars who comment on Hume’s essay believe, a method just for critics to apply, but rather a guide for any individual to engage in an aesthetic experience. Hume tells us that one of the aims of the essay is “to mingle some light of the understanding with the feelings of sentiment,” so the faulty of delicacy of taste takes a central role in Hume’s theory. Such faculty can and should be improved and developed, which leads us to think that the process Hume describes is not only for the critics but open to anyone.

- “But though there be naturally a very wide difference in point of delicacy between one person and another, nothing tends further to encrease and improve this talent,than practice in a particular art, and the frequent survey or contemplation of a particular species of beauty.” (OST, 220)

If we want to derive the most pleasure out of our aesthetic experiences we need to experiment with works of art in order to develop our delicacy of taste.

If we accept this reading of Hume’s essay we can shed light on its purpose. It was not the attempt to establish a standard of taste, but rather a guide for engaging with works of art and to have discussions regarding matters of taste.

Early modern x-phi: a genre free zone

Peter Anstey writes…

One feature of early modern experimental philosophy that has been brought home to us as we have prepared the exhibition entitled ‘Experimental Philosophy: Old and New’ (soon to appear online) is the broad range of disciplinary domains in which the experimental philosophy was applied in the 17th and 18th centuries. Some of the works on display are books from what we now call the history of science, some are works in the history of medicine, some are works of literature, others are works in moral philosophy, and yet they all have the unifying thread of being related in some way to the experimental philosophy.

Two lessons can be drawn from this. First – and this is a simple point that may not be immediately obvious – there is no distinct genre of experimental philosophical writing. Senac’s Treatise on the Structure of the Heart is just as much a work of experimental philosophy as Newton’s Principia or Hume’s Enquiry concerning the Principles of Morals. To be sure, if one turns to the works from the 1660s to the 1690s written after the method of Baconian natural history, one can find a fairly well-defined genre. But, as we have already argued on this blog, this approach to the experimental philosophy was short-lived and by no means exhausts the works from those decades that employed the new experimental method.

Second, disciplinary boundaries in the 17th and 18th centuries were quite different from those of today. The experimental philosophy emerged in natural philosophy in the 1650s and early 1660s and was quickly applied to medicine, which was widely regarded as continuous with natural philosophy. By the 1670s it was being applied to the study of the understanding in France by Jean-Baptiste du Hamel and later by John Locke. Then from the 1720s and ’30s it began to be applied in moral philosophy and aesthetics. But the salient point here is that in the early modern period there was no clear demarcation between natural philosophy and philosophy as there is today between science and philosophy. Thus Robert Boyle was called ‘the English Philosopher’ and yet today he is remembered as a great scientist. This is one of the most important differences between early modern x-phi and the contemporary phenomenon: early modern x-phi was endorsed and applied across a broad range of disciplines, whereas contemporary x-phi is a methodological stance within philosophy itself.

What is it then that makes an early modern book a work of experimental philosophy? There are at least three qualities each of which is sufficient to qualify a book as a work of experimental philosophy:

- an explicit endorsement of the experimental philosophy and its salient doctrines (such as an emphasis on the acquisition of knowledge by observation and experiment, opposition to speculative philosophy);

- an explicit application of the general method of the experimental philosophy;

- acknowledgment by others that a book is a work of experimental philosophy.

Now, some of the books in the exhibition are precursors to the emergence of the experimental philosophy (such as Bacon’s Sylva sylvarum). Some of them are comments on the experimental philosophy by sympathetic observers (Sprat’s History of the Royal Society), and others poke fun at the new experimental approach (Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels). But this still leaves a large number of very diverse works, which qualify as works of experimental philosophy. Early modern x-phi is a genre free zone.