Buffon and the Experimental Philosophy

Peter Anstey writes …

The historiography of the Enlightenment over the last fifty years has focused heavily on the influence of the natural philosophy of Bacon and Newton and the philosophy of Locke on the French philosophes.

Surprisingly, however, the thought of Bacon, Locke and Newton has rarely been seen as part of the broader impact of the experimental philosophy movement: the focus has been on individuals and their thought and experimental philosophy has been regarded as an expression of the ‘empiricism’ of these thinkers. See for example, Jonathan Israel’s monumental Radical Enlightenment and Democratic Enlightenment, neither of which lists ‘experimental philosophy’ in its index and which tend to subordinate English experimental philosophy to empiricism. (The term gets a mere 4 entries in the index of his 983-page Enlightenment Contested.)

Now, one text that has been repeatedly cited as early evidence of the important impact of Newton is Buffon’s Translator’s Preface to his 1735 French translation of Stephen Hales’ Vegetable Staticks of 1727. But when we turn to the text itself it’s pretty clear that Newton is merely an exemplar of a broader phenomenon.

As we have argued many times on this blog, the experimental philosophy that emerged in England in the 1660s was characterized by an emphasis on observation and experiment, an aversion to theoretical systems and especially its decrying of hypotheses and principles. Let us look at Buffon’s Preface and see what he has to say about Hales’ book. He says:

- The novelty of the discoveries and the majority the ideas [of Hales’ book] will no doubt surprise natural philosophers. I know nothing better of its kind, and the genre itself is excellent, for it is only experiment and observation.

- … works founded on experiment, merit more than others. I can even say that in natural philosophy, one ought to search out experiments as much as one ought to be afraid of systems. I admit that there is nothing so good as to establish first a single principle, and then to explain the universe, and I am convinced that if one were so happy to divine it, all the pain that it takes to make experiments would be unnecessary. But sensible people see rather how much this idea is vain and chimerical: the system of nature probably depends upon several principles, principles that are unknown to us and their combination even less so.

- … It is by choice experiments, reasoned and followed, that one forces nature to reveal its secret. All the other methods have never succeeded.

- … Collections of experiments and observations are therefore the only books that can augment our understanding. Being a natural philosopher is not a matter of knowing what follows from this or that hypothesis, in supposing, for example, a subtle matter, vortices, an attractive force, etc. It is to know well that by which it comes and to understand that which is presented to our eyes. The understanding of effects will conduct us insensibly to that of their causes and will not trip us up into the absurdities that seem to characterize all systems.

- … It is this method that my author [Hales] has followed. It is that of the great Newton; that which Bacon, Galileo, Boyle, Stahl recommended and embraced; that which the Académie of Sciences has made it a law to adopt … (pp. iii–vi)

Notice the underlined words here: ‘experiment and observation’, ‘systems’, ‘vain and chimerical’, ‘hypothesis’. This passage bears all the hallmarks of an expression of the central doctrines of the experimental philosophy. This is reinforced by the gallery of greats that is listed: Bacon, Galileo, Boyle, Stahl.

The focus is not on individuals such as Newton at all, nor is it on empiricism. It is on the méthode of the experimental philosophy. This is what Voltaire had referred to just one year earlier in 1734 in his letter ‘On the Lord Bacon’ in his Letters concerning the English Nation, where he claimed that Bacon ‘is the Father of experimental philosophy’ and that ‘no one before the Lord Bacon was acquainted with experimental Philosophy’.

It is the experimental philosophy, and not Bacon or Newton, that Buffon is praising and advocating. The experimental philosophy, as discussed by Buffon, Voltaire, d’Alembert and Diderot, needs to become a central notion in our historiography of the Enlightenment.

Explicating Newton’s Natural Philosophical Methodology: Part II

This is the second part of Steffen Ducheyne’s presentation of his new book, “The main Business of Natural Philosophy:” Isaac Newton’s Natural-Philosophical Methodology. You can find the first part here.

Steffen Ducheyne writes …

In the Principia (1687), Newton developed a detailed picture of how one may deduce causes from phenomena (for the technical details I refer to Chapters 2 and 3). Newton’s expression ‘deductions from phenomena’ has oftentimes been considered as a rhetorical tool by which he sought to distance himself from his opponents. However, close scrutiny shows, I believe, that Newton’s ‘deductions from phenomena’ have profound methodological significance as well. I do not, however, endorse the view that Newton’s Principia-style methodology was therefore non-hypothetical. Rather, what makes it methodologically interesting is that it encompassed procedures to minimize speculation and inductive risk in the process of theory formation. What is distinctive of Newton’s Principia-style methodology is that he established bi-conditional dependencies between causes and their effects from the laws of motion. In other words, the causes which Newton would later infer in Book III were backed-up and constrained by the laws of motion. Given these dependencies, Newton was able to present his derivations of the centripetal forces acting in our solar system as deductions and, hence, as ‘deductions from phenomena’. I want to emphasize, however, that Newton’s proceeding from phenomena to theory, i.e. his presenting of certain inferences as deductions from phenomena, taken as such is not what makes his method essentially different from hypothetico-deductivism. Rather, proceeding from phenomena to theory is the by-product of what genuinely makes Newton’s method distinctive from hypothetico-deductivism: the establishment of systematic dependencies backed-up by the laws of motion. These systematic dependencies, in other words, mediate between experimental or astronomical results and the very causes which account for these phenomena.

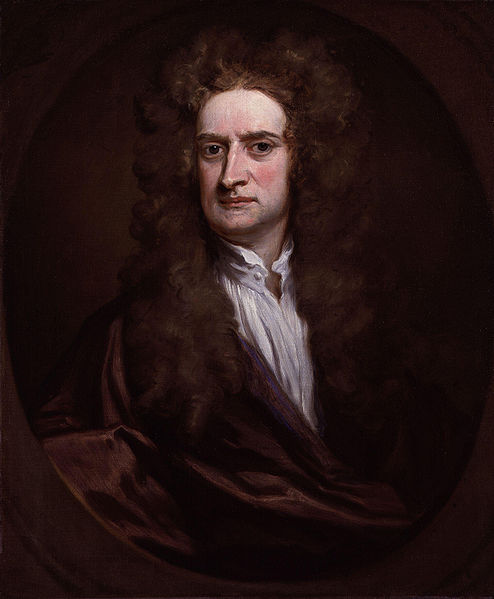

Portrait of Isaac Newton (1702)

Once he had finished the Principia, Newton returned to his optical studies, which would eventually lead to the publication of the Opticks in 1704. Could he now methodize optics according to the highly sophisticated standards which he had developed in the Principia? In my view, the answer is negative. For instance, I have argued that Newton’s argument for the heterogeneity of light rests on an argument of uniformity that cannot be licensed by Newton’s second rule of philosophizing. I have also paid considerable attention to the problem of transduction which Newton encountered in his optical studies. In mechanics, the affected entities, i.e. the explananda – bodies moving along specific trajectories, and their constituent elements, namely, the particles constituting these very bodies – all have a theoretically salient property in common, namely, mass. Because gravity is proportional to mass and because the latter is additive, gravity is likewise additive. This allowed Newton to show that a body’s overall force can be decomposed into the individual forces of each of the bodies constituting that body and vice versa. In optics, by contrast, we do not know – at least not without speculating on the matter – the constituting elements of the explananda. In the Opticks Newton could not establish ‘deductions from phenomena’ because, in contrast to the physico-mechanical theory of the Principia, a mixed science describes a given phenomenon mathematically without an accompanying explanatory story. In other words, in the Opticks the inference of causes could not be constrained by a set of laws which carry information about the proximate causes involved.

By way of outro and also as a teaser, I would like to conclude by devoting some words to the provisionalism that characterized Newton’s later methodological thought. Newton’s provisionalism pervades the third and especially the fourth regula philosophandi, which were added in the second (1713) and third (1726) edition of the Principia, respectively. The provisionalism which Newton envisioned did not apply to the ‘deductions from phenomena’, but rather to propositions ‘rendered general by induction’ – at least evidence from Newton’s manuscripts leads me to believe so. Based on a careful study of Newton’s manuscripts, I have also succeeded in clarifying what Newton understood by qualities which cannot be “intended and remitted” and, on the basis of this, I have concluded that the Cohen-Whitman translation of “intendi et remitti” as “increased and diminished” is incorrect. I could say much more about my book, but I hope that this will suffice to get you interested in reading it.

Explicating Newton’s Natural Philosophical Methodology: Part I

Steffen Ducheyne writes …

The research team at Otago has kindly invited me to discuss some of the central ideas of my recent monograph “The main Business of Natural Philosophy”: Isaac Newton’s Natural-Philosophical Methodology. My aim in this and next week’s guest post is not to give a complete overview of my book, but rather to bring some salient features of Newton’s methodology to the fore insofar as they are relevant for the speculative-experimental distinction.

Newton sought to separate hypotheses from demonstrations from within natural or experimental philosophy. This, in my view, adds an interesting dimension to the speculative-experimental distinction, for it shows how the distinction was transformed and introduced in the realm of natural philosophy. Newton’s preoccupation with methodological rigour and his distaste of hypotheses led him to explicate the conditions under which our conclusions about the physical world are to be considered as truthful. In this process, he would develop a highly sophisticated methodological position the kind of which had never been seen before.

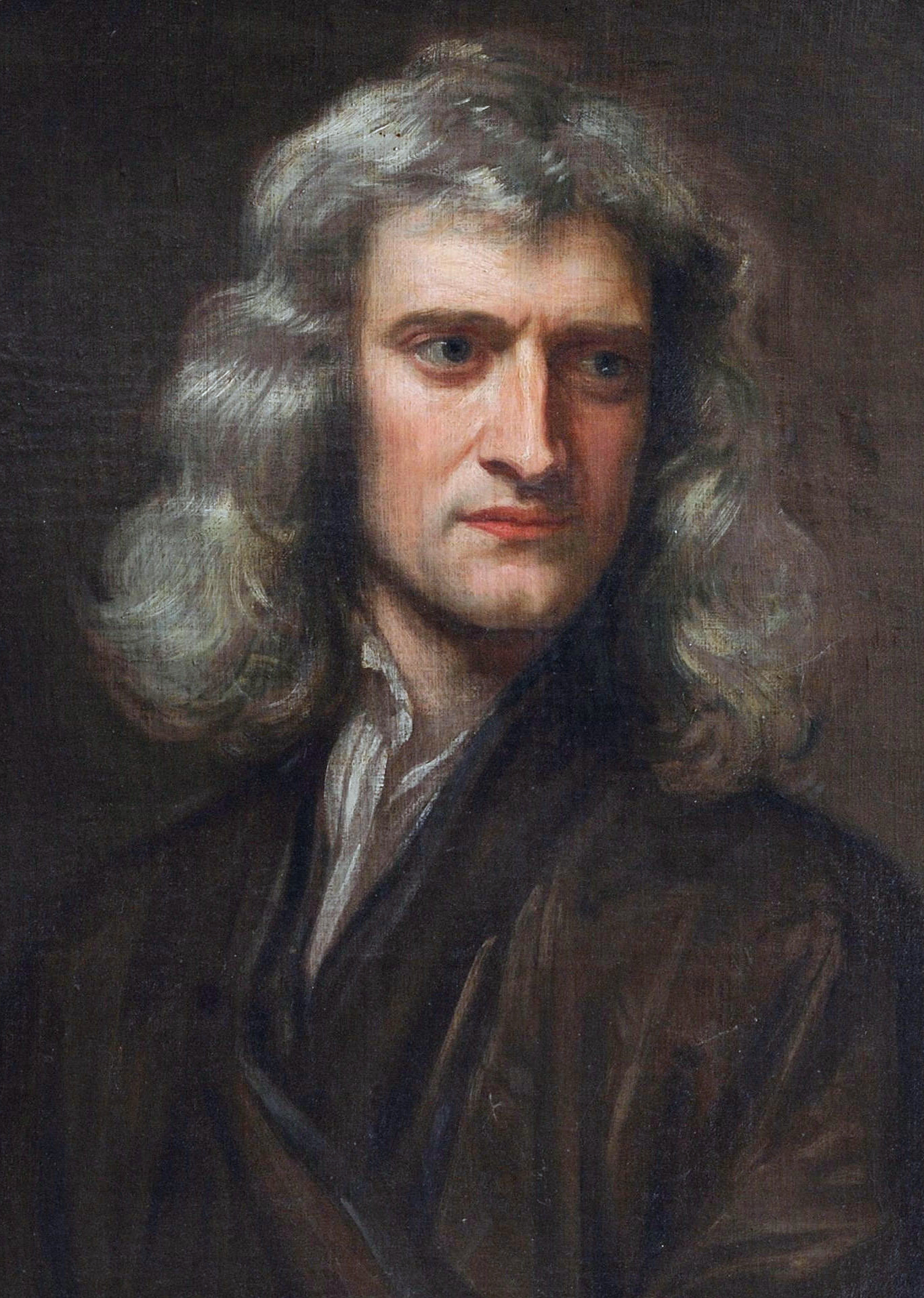

Portrait of Isaac Newton (1689)

Before turning to a discussion of Newton’s methodology proper, however, I would like to say something on how I have approached Newton’s methodology. Oftentimes, Newton’s methodology has been approached as if it was a stable given that remained fixed throughout his natural-philosophical career. In my book I have argued that Newton’s methodological views developed alongside with his natural-philosophical research. In Chapter 5, moreover, I distinguish between four distinct phases in the development of Newton’s methodological thought. Furthermore, although Newton clearly favoured his Principia-style methodology, which sets out to physico-mathematically ‘deduce’ causes from their effects, and considered it as the one to be followed ideally, Newton also relied on different methodologies. For instance, in the demonstrative parts of the Opticks he made use of a mixed mathematics treatment and in its speculative parts he proposed hypotheses to be investigated further. In my monograph I have called attention to important diachronic and synchronic differences in Newton’s methodological thought.

Newton’s first optical paper (1671/2) was not only a scientific debut, he also introduced a new methodological ideal on how knowledge about the empirical world is to be established. That ideal consisted in deducing causes from phenomena with demonstrative certainty. In the unedited version of his first optical paper, Newton stated the following on his theory of the heterogeneity of white light: “For what I shall tell concerning them [i.e. colours] is not a Hypothesis but most rigid consequence, not conjectured by barely inferring ’tis thus because not otherwise or because it satisfies all phænomena […] but evinced by ye mediation of experiments concluding directly & without any suspicion of doubt.” In the same period, he criticized the use of hypotheses in natural philosophy. At this point, important features of Newton’s methodological views were in place: his rejection of hypotheses, his ideal of deducing causes from phenomena, his conviction that by injecting mathematics into natural philosophy the latter could partake in the certainty of the former, his endeavour to draw conclusions from experiments, and his desire to treat of light ‘abstractly’, i.e. without making statements on the nature of light. Yet, as I argue in detail in Chapter 4, Newton’s methodological position was at that point still lacking elaboration and justification. That Newton did not provide much detail on how the heterogeneity of white light is derived from the experimentum crucis illustrates the lack of elaboration that characterized Newton’s early methodological views. In next week’s post I will summarize just how Newton’s methodological views developed from the publication of the first edition of the Principia in 1687.

Aberdeen’s 1755 Plan of Education

Juan Gomez writes …

One of the topics we have covered in this blog is education. I have commented on David Fordyce’s ideas, and Gerhard Wiesenfeldt contributed to the blog with two very interesting posts on Speculative and Experimental Philosophy in Universities (Post-Cartesianism and Eclecticism). In this post I want to expand on this topic and tell you about Alexander Gerard‘s Plan of Education.

As we have mentioned throughout various posts in this blog, one of the features of those allied with experimental philosophy was their disdain for the scholastic school of thought and the rejection of mere speculation. This led the regents and teachers in Colleges and Universities to revolt against the scholastic teaching system and promote a change in the way education was structured. In Aberdeen, the first stages of this project of reformation started with the teachings of George Turnbull and Colin MacLaurin in the 1720’s, but we had to wait until the 1750’s for the reform of the curriculum. It was written by Alexander Gerard and published in 1755. It gives us a good overview of what the members of the faculty found wrong with the scholastic mode of thinking and the central role experimental philosophy (and the experimental method) should take in the colleges and universities.

Gerard begins by explaining why the faculty members at Marischal college have decided to reform the method of education. The method used in most European universities, Gerard tells us, was that of the Peripatetic Philosophy ‘espoused by the Scholastics’. This is his description:

- The chief business of that Philosophy, was, to express opinions in hard and unintelligible terms; the student needed a dictionary or nomenclature of the technical words and authorized distinctions; experiment was quite neglected, science was to be reasoned out from general principles, either taken for granted, or deduced by comparison of general ideas, or founded on very narrow and inadequate observation: Ontology, which explained these terms and distinctions, and laid down these principles, was therefore introduced immediately after logic. By these two, the student was sufficiently prepared for the verbal, or at best, ideal inquiries of the other parts.

Fortunately, the state of philosophy had changed:

- [Philosophy] is become an image, not of human phantasies and conceits, but of the reality of nature, and truth of things. The only basis of Philosophy is now acknowledged to be an accurate and extensive history of nature, exhibiting an exact view of the various Phenomena for which Philosophy is to account, and on which it is to found its reasonings.

This change in Philosophy posed a problem for a system that was based on Scholastic methods. If philosophy is founded on facts and observation, from which we then derive the terms or notions, the system of education was flawed by teaching first the notions and principles without any experience of the facts they refer to. The teachers at Marischal proposed to restructure the order in which the different subjects were taught. Instead of starting with Logic and Ontology, the students “after being instructed in languages and classical learning, be made acquainted with the Elements of History, Natural and Civil, of Geography and Chronology, accompanied with the Elements of Mathematics; that they should then proceed to Natural Philosophy, and, last of all, to Morals, Politics, Logic and Metaphysics.” This new curriculum was much better suited for the pursuit of knowledge and the aims and methods of the new philosophy.

Most of the pamphlet is an attack on the scholastic system that justifies the decision of the Masters of the college to leave the teaching of Logic to the final year. There are constant references made to the importance of facts, experiments, and observations as the sole foundation of knowledge. Any sort of purely speculative way of thinking was not to be included in education. But the promoters of this reform were not claiming that logic and metaphysics were of no use at all; what we need to understand is that they are entirely dependent on all the other sciences, and if they are to contribute in our search for knowledge, then they must come after all the other sciences. The attack of the promoters of the methods of the experimental philosophy was not against speculative subjects themselves, but against the scholastic methods of education that considered speculation to be more important than our knowledge of the natural world.

Experimental Philosophy and the Straw Man Problem

Peter Anstey writes …

One common objection against the experimental–speculative distinction (ESD) as an alternative historiographical framework for understanding early modern philosophy is the Straw Man Problem. Our interlocutors are prepared to admit the importance of the emergence of the experimental philosophy in Britain in the mid-seventeenth century and its subsequent uptake across the Continent. However, they object that, in spite of all the experimental philosophers’ rhetoric, there were few, if any, speculative philosophers. The speculative philosopher, in their view, is merely a straw man, a creation of the experimental philosophers who needed someone or something to define themselves against. The claim, then, is that there was not really any substantive experimental–speculative distinction because there were not really any speculative philosophers.

In my view this objection is based upon a superficial understanding of the ESD. Moreover, I believe that providing an adequate response to the Straw Man Problem is a good way to highlight what is at the core of the ESD framework.

A weakness of the Straw Man objection is the presumption of parity: it is assumed that if we have an actual distinction then we have practitioners of, more or less, equal number on both sides of the distinction. This presumption may derive from the Kantian rationalism–empiricism historiography with its two triumvirates of Descartes, Leibniz and Spinoza versus Locke, Berkeley and Hume. Be that as it may, it is certainly true that there were very few advocates of speculative philosophy after the 1660s. In Britain, Thomas Hobbes, Margaret Cavendish and John Sergeant were all opponents of the experimental philosophy and so might be classed as speculative philosophers, but it’s hard to name any others.

Nevertheless, this lack of parity does nothing to undermine the ESD. For, what is important is that it is the method, content and characteristics of speculative philosophy that were the focus of experimental philosophers’ attacks and disdain and not, on the whole, the practitioners themselves.

The ESD is, therefore, in the first instance a distinction that pertains to natural philosophical (and later philosophical) methodology and only secondarily to individuals. A nice analogue here is found in twentieth-century philosophy of mind. From the 1970s most philosophers were materialists or physicalists about the mind and it became hard to name any substance dualists. And yet physicalists about the mind defined their position, in large part, as being distinct from and opposed to dualism. Anyone who has done even the most cursory reading in the philosophy of mind knows that there is an historical explanation of this phenomenon. The Identity Theory emerged in the 1960s on the back of the attack on the ‘ghost in the machine’ by Gilbert Ryle and others. Early materialist theories of the mind were new and radical in so far as they defined themselves against dualism, even if within a few decades there were hardly any dualists to be found.

A similar situation is to be found with the emergence and growth of early modern experimental philosophy. There had been a long tradition in philosophy of distinguishing between speculative and operative philosophy, between speculative and operative knowledge and even speculative and operative intellects. Natural philosophy had almost invariably been classified as a speculative science. The conceit of the Fellows of the early Royal Society (among others) was to claim not only that natural philosophy could also be an operative (that is, experimental) science, but that the operative method of natural philosophy is far superior to the old speculative approach.

Thus, in order to explain the nature of the ESD, we shouldn’t look forward from the mid-seventeenth century for parity among practitioners from either side, rather we should look back to the origins of the distinction. In so doing it becomes clear that the speculative philosopher is no straw man.

Experimental vs Speculative Philosophy in Early Modern Italy

Alberto Vanzo writes…

So far, we have argued in many posts that British philosophers from the 1660s onwards worked in the tradition of experimental philosophy and criticized speculative philosophy. However, the distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy was also widely employed outside the British isles. In this post, I will document the presence of the experimental-speculative distinction in Italian natural philosophy between 1667 and 1716.

The Accademia del Cimento, founded by 1657 by Prince Leopoldo de Medici in Florence, was one of the first scientific societies in Europe. In 1667 the Accademia published a collection of experimental reports with the title Saggi di naturali esperienze. The preface to this work ends with a caveat:

- We would not like anyone to believe that we presume to give to the light a complete work, or even only a perfect scheme of a great experimental history, because we know well that more time and strengths are required for such an enterprise […] if, sometimes, an even minimal allusion to anything speculative has been made, […] always take it to be a specific idea or intuition of [some] academics, but never one of the Accademia, whose only aim is to experiment and to narrate.

Note the emphasis on experiments, the references to natural histories, and the refrain from endorsing any speculation. These are all indications that the Academy was presenting its work in terms of the then nascent distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy.

Not everyone was endorsing experimental philosophy in late seventeenth-century Italy. However, some of the authors who expressed reservations towards it did so in terms of the experimental-speculative distinction. For instance, Daniello Bartoli distinguished in 1677

- the two manners of natural philosophy which nowadays are very rumored, because they fight over the glory of primacy […]: the Theoretical and the Experimental […]

On the one hand, theoretical or “purely speculative” philosophy “needs experimental [philosophy] to “see [things] by means of the senses”. On the other hand, “purely experimental” philosophy must seek the help of speculative philosophy to proceed from particular experiences to their causes.

- [E]ither [philosophy], by itself, can be defeated if the other does not help and rescue it when it may fall down. But if both are united and if they fight side by side, although they may not always win, surely they will never be defeated.

Among the Aristotelians, Giovanni Battista de Benedictis (writing under the pseudonym of Benedetto Aletino) criticized experimental philosophy for its inability to proceed from facts to causes. He claimed that experimenters were not philosophers, but mere empirics, because they failed to establish any evident, undisputed premises as the basis for a deductive scientia of nature.

- Indeed, if our Peripatetics, who only paid attention to speculative subtleties, had followed Aristotle’s teachings by directing their efforts towards experience, I have no doubt that they would have unfailingly attained the glory that the Atomists [i.e., experimental philosophers] are now seizing, not because of their knowledge, but because of the neglicence of others [the Peripetetics].

While Aletino defends the Aristotelians, he categorizes them as speculative philosophers and he rejects experimental philosophy.

Antonio Conti was a Venetian abbot who acted as intermediary in the epistolary exchange between Leibniz and Newton. He published a discussion of the relation between experimental and speculative philosophy in 1716. For Conti, experimental philosophy alone “is truly science” because it rely on experience to prove the truth of its claims. By contrast, speculative or conjectural philosophy can only establish the probability or truth-likeliness of hypotheses. Due to the endless variety of nature and the limitations of our senses, Conti did not think that experimental philosophy could eventually supplant all speculations. His fallibilism concerning hypotheses sounds rather modern:

- One makes hypotheses to establish [new] ideas and experiences; but hypotheses last only until phenomena modify or destroy them, or until a more perfect art of comparing truth-likely [statements] proves their uselessness or their imprudence.

Like Bartoli, Conti endorsed experimental philosophy without wholly rejecting the speculative approach. Bartoli and Conti, like Aletino and the compiler of the Saggi di naturali esperienze, thought of natural philosophy in terms of the experimental-speculative distinction. As in the British isles, so also in Italy the experimental-speculative distinction provided important terms of reference for thinking about nature in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

In this post, I have not discussed to what extent the experimental-speculative distinction shaped the contents, besides the rhetoric and methodology, of Italian natural philosophy. I must do more work to answer that question. In the meanwhile, let me know what you think in the comments.

Miracles and ‘Experimental Theism’

Juan Gomez writes…

Greg Dawes pointed out to me a passage in David Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion where we find the term ‘experimental theism.’ In this text, Hume seems to be referring to an argument given by one of the characters in the dialogue, Cleanthes, where the principle “like effects prove like causes” functions as a premise in an argument for a Deity. But what is really striking is that the term “experimental theism” nicely describes the approach George Turnbull takes in his religious texts, the Principles of Christian Philosophy (1749) and the earlier Philosophical Enquiry Concerning the Connexion Between the Doctrines and Miracles of Jesus Christ (1731). In this post I want to look at the earlier religious text and examine Turnbull’s exposition of what I believe is his ‘experimental theism’.

Turnbull constantly refers to the way natural philosophy is practised in order to adopt the same methods in inquiries into any kind of knowledge at all, whether moral or natural (see my previous posts here and here). His text on the Doctrines and Miracles of Jesus Christ is no exception. The interesting aspect of this text is that Turnbull draws an analogy between experiments and miracles. His argument begins by explaining how we come to know the laws of matter and motion:

- It is by experiment, that the natural philosopher shews the properties of the air, for example, or of any other body. That is, the philosopher shews certain effects which infer certain qualities: or in other words, he shews certain proper samples of the qualities he pretends the air, or any other body that he is reasoning about, hath. Thus is it we know bodies gravitate, attract, that the air is ponerous and elastic. Thus it is, in one word, we come to the knowledge of the properties of any body, and of the general laws of matter and motion.

This is the same way we can know if someone possesses a particular, skill, power, knowledge, or character:

- ’Tis by proper samples or experiments only of power and knowledge, that we can be assured, one actually possesses a certain power of knowledge. Just so it is only by samples or experiments, that we can judge of one’s honesty, benevolence, or good intention.

In the same way, “It is from the works of the Supreme Being, that we infer his infinite wisdom, power and goodness; as from so many samples and experiments, by which we may safely judge of the whole.” This is way of proving through ‘samples and experiments’ is what allows Turnbull to draw the connection between the Doctrines and the miracles. The miracles are sufficient proof of the doctrines, since they are the samples and experiments that show that Jesus has the set of powers entailed by the three kinds of doctrines of Christianity Turnbull identifies: the doctrine of future rewards and punishments, of resurrection of the dead, and of the forgiveness of sins.

Turnbull begins by examinig the doctrine of the resurrection of the dead. He tells us that Jesus has claimed that he has the power to raise the dead. How can we tell if this is the case or not? Well we need samples and experiments:

- It was necessary to give samples, or experiments, of this power he claimed. And accordingly he raised from the dead; and gave power to his apostles to raise from the dead. And to put his pretensions beyond all doubt, he himself submitted to death, that he might give an incontestible proof of his being actually possessed of that power, by rising himself from the dead the third day, according to his own prediction.

Within this theory, miracles are analogous to the experiments and facts that work as proof for theories about the natural world. Turnbull examines the other two kinds of doctrine in a similar manner and concludes that Jesus Christ has given proper proof of having the powers he has claimed to have, and as evidence Turnbull cites the many passages in the New Testament where we find anecdotes of the miracles performed by Jesus Christ. The analogy is further explained when Turnbull considers the fact that we cannot understand the nature of miracles. It is not necessary that we understand the nature of the miracle, since it is still proof of the power of performing such miracle. This is the case with attraction in natural philosophy:

- Attraction, say all the philosophers, is above our comprehension: they cannot explain how bodies attract: but experience or samples certainly prove that there is attraction. And proper experiments or samples, must equally prove the power of raising the dead, tho’ we do not understand, or cannot explain, that power.

There are many interesting aspects in Turnbull’s religious thought worth looking into, but for now I’ll leave you with the few snippets provided here. The most relevant feature of Turnbull’s explanation of miracles is that it shows how committed he was to applying the experimental method to any sort of inquiry. He did this in moral philosophy, and here he does it regarding religion. Besides the use of the rhetoric of the experimental philosophy and the consideration of miracles as experiments, he even concludes the text with a list of queries, providing us with some insight of what a work of ‘experimental Theism’ would look like.

Von Haller on hypotheses in natural philosophy

Alberto Vanzo writes…

Typically, the experimental philosophers on whom we focus in this blog promoted experiments and observations, while decrying hypotheses and system-building. This is the case for several experimental physicians, to some of whom we have devoted the last two posts. Their Swiss colleague Albrecht von Haller thought otherwise. He published an apology of hypotheses and systems in 1751.

Von Haller was a novelist, a poet, and an exceptionaly prolific writer on nearly all aspects of human knowledge. He is said to have contributed twelve thousand articles to the Göttingische gelehrte Anzeigen. However, von Haller was mainly employed as an anatomist, physiologist, and naturalist. Like his Scottish colleague Monro I, he had studied in Leyden under Boerhaave. Having achieved Europe-wide fame for his physiological and botanical discoveries, von Haller was called by George II of England, prince-elector of Hanover, to occupy the inaugural chair of medicine, anatomy, botany and surgery at the newly founded University of Göttingen. Göttingen was under the strong influence of British culture throughout the eighteenth century and would later be the main centre of German experimental philosophers. While in Göttingen, von Haller was mainly engaged in his physiological and botanical studies, besides organizing an anatomical theatre, a botanical garden, and other similar institutions.

Haller’s essay, entitled “On the Usefulness of Hypotheses”, was first published as a premise to the German edition of Buffon’s Natural History. It was reprinted posthumously in 1787. Throughout these years, several authors in the German speaking-world endorsed Newton’s radically negative attitude towards hypotheses. For instance, few years after von Haller’s essay the physician Gerard van Swieten — also a pupil of Boerhaave — published a discourse on medicine in which he cried “may hypotheses be banned!”. And in the 1780s, when von Haller’s essay was being reprinted, the anthropologist Johann Karl Wezel proclaimed in broadly Newtonian spirit: “I only relate facts”.

Von Haller was aware of this anti-hypothetical fashion. He starts his essay by describing how naturalists had come to despise hypotheses. With the success of mathematical natural philosophy (the Newtonian form of experimental philosophy that had replaced Baconian natural histories), researchers started to rely (or at least, to claim that they were only relying) on what had been mathematically proven. This happened first in England with Newton, then in Holland with Boerhaave, then in Germany and France with Maupertuis and others.

For Haller, this was not a positive development. Peopled shifted from one excess, namely abusing of hypotheses, to an other, namely rejecting them altogether, while ignoring the virtuous middle way. Yet, while researchers were despising hypotheses, they were relying heavily on them:

- The great advantage of today’s higher mathematics, this dazzling art of measuring the unmeasurable, rests on a mere hypothesis. Newton, the destroyer of arbitrary opinions, was unable to avoid them completely. […] His universal matter, the medium of light, of sound, of the senses, of elasticity — was it not a hypothesis?

Von Haller makes other examples of natural-philosophical hypotheses, in order to highlight

- the true use of hypotheses. They are certainly not the truth, but they lead to it, and I say even more: humans have not found any way that is more successful in leading them to the truth [than hypotheses], and I cannot think of any inventor who did not make use of hypotheses.

What is this “true use of hypotheses”? It is their heuristic use. Hypotheses are claims to be tested by means of experiments and observations. Sets of hypotheses form large-scale systematic pictures that provide purpose and direction to our research. Think for instance of the heuristic value of the corpuscular hypothesis for the experimental activity of the early Royal Society (this is not von Haller’s example). Additionally, hypotheses make possible a public discussion of problems that scientists could not even mention if they were only allowed to talk about were facts, as some experimental philosophers hoped.

These experimental philosophers may reply to von Haller that they do not need to employ hypotheses to achieve those aims. All that is needed are queries. Von Haller would reply that queries are nothing else than hypotheses in disguise. “In fact, Hypotheses raise questions, whose answer we demand from experience, questions that we would not have raised if we did not formulate hypotheses”.

Von Haller was not the only author in the German-speaking world to provide a qualified defense of hypotheses. Christian Wolff before him and Immanuel Kant after him made similar points. However, von Haller was much more engaged in empirical research than either of them. His work seems to me to have been very much in the spirit of experimental philosophy. Finding such an explicit and detailed defense of hypotheses by such an author reminds us that the methodological views of early modern experimentalists were not monolithic and that, even in a strongly anti-hypothetical age, some authors were aware of the benefits of a careful use of hypotheses in the study of nature.

Experimental medicine and the Monro dynasty

Juan Gomez writes…

Following Peter Anstey’s post on 17th-century experimental medicine I want to continue shedding light on the topic, but I will be focusing on 18th-century experimental medicine. In particular, I want to examine the Monro dynasty and the role they played in the instruction of medicine in Edinburgh for more than a hundred years.

From 1726 until 1846 the chair of anatomy at the University of Edinburgh was held by the members of the Monro family. Alexander Monro Primus (1697-1767) held it from 1726 until 1754; his son Alexander Monro Secundus (1733-1817) succeeded him in 1758; and Alexander Monro Tertius (1773-1859) held the chair from 1817 until 1846. While Tertius’ relevance lies on the fact that he continued the work of his father and grandfather, Primus and Secundus are one of the main reasons why the medical school at Edinburgh was considered the best of its time. Of course, the experimental method applied by the Monro’s was one of the reasons for their success.

Monro Primus studied at Leiden under Herman Boerhaave in 1718, and by in 1720 he was back at Edinburgh giving public lectures on anatomy. In 1726 he published his Anatomy of the Humane Bones, which was widely read throughout the eighteenth century. The book was intended to be used by those students attending Monro’s lectures, where he demonstrated on corpses to illustrate the theory. In fact, the Professor’s insistence on the importance of performing dissections on corpses for his lectures was such that it was suspected that Monro and his students were grave robbing. In the preface to the second edition of his book Monro claims that all the facts included in his book, even those he has taken from other authors have been confirmed by experiments:

- In executing these [parts I and II of his book], I have taken all the assistance I could from Books, but have never asserted any anatomical Fact on their Authority without consulting the Life, from which all the Descriptions are made; and therefore the Quotations from such Books, serve only to do Justice to the Authors… Besides anatomists, I have also named several other Authors [for example Boyle] to confirm my reasoning by practical Cases.

Monro Primus was a very active figure in the Edinburgh enlightenment. As the editor of the volumes of essays published by his Medical Society of Edinburgh, he calls for the emphasis on facts and observation of the experimental method to be applied in Medicine. He tells us that he ‘principal part of medicine is:

- The Knowledge and Cure of Diseases, which chiefly depend on Observations of Facts that ought to be frequently repeated before any certain Axiom in Physick can be built on them.

Monro Primus’ work was continued by his son. Though Secundus continued using the text written by his father in his anatomy lectures, he published and contributed to the knowledge of the brain and the nervous system. All his texts contain detailed descriptions of the experiments he performed, besides the constant use of the rhetoric of the experimental philosophy and methodological statements confirming the use of experimental methods in medicine. A lot of his work stems from experiments performed on animals, notably a number of essays published in the collection of essays of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and his 1793 book Experiments on the nervous system, with opium and metalline substances, made chiefly with the view of determining the nature and effects of animal electricity. The way such book is structured is typical of experimental philosophy. Monro begins by giving some observations on the nervous system of frogs (which he used for his experiments); this is followed by a detailed description of the experiments and then he deduces “Corollaries from the above Facts and Experiments.”

In an earlier book, where he describes in some detail his main claim to fame (the discovery of the interventricular foramen of the brain), he calls for a stop to speculation and focus instead on facts and experiments. He refers to an experiment carried out by Dr. Albrecht von Haller which he describes and then tells us:

- But instead of speculating farther, let us learn the effects of experiments and endeavour from these to draw plain conclusions.

The contrast between speculative and experimental approaches is also stated in his last major work, Three Treatises. On the Brain, the Eye and the Ear (1797):

- An anatomist, reasoning a priore, would be apt to suppose, that the Water, in the Hydrocephalus Internus, should be as often found immediately within the Dura Matter, between it and the Outer-side of the Brain, Cerebellum, and Spinal Marrow, as within the Ventricles of the Brain. Experience, however, proves that it is generally collected within the ventricles; and, as I have not met with a single instance in which the Water was entirely on the Outer-side of the Brain, (although I am far from doubting the possibility of the fact), I cannot help suspecting that this happens much more rarely than it is supposed by Authors.

We can see then that the call for the application of the experimental method in medicine that started in the seventeenth century was characteristic of the medical school at Edinburgh in the eighteenth century. With the Monro dynasty in charge, the methodology promoted by Herman Boerhaave (Primus’ teacher) became the preferred for the training and practice of physicians in Scotland, with the Edinburgh medical school rising to its reputation of the best school in the world.

Experimental medicine in mid-17th-century England

Peter Anstey writes …

In my last post I claimed that the London physician Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689) faced much opposition during his professional career, and yet his posthumous reputation was that of the experimental physician par excellence. But was Sydenham the first experimental physician, the first English Hippocrates?

This question raises, in turn, the further issue of the extent to which the experimental philosophy, which emerged in England in the late 1650s and early 1660s, influenced English medicine. The hallmarks of Sydenham’s method – at least as championed by John Locke, the Dutch physician Herman Boerhaave and the Italian Giorgio Baglivi – were his commitment to natural histories of disease, his strident opposition to hypotheses and speculation, and his strong emphasis on observation. Interestingly, each of these methodological tenets can be found in the writings of physicians, and especially the chymical physicians (who opposed the Galenists of the College of Physicians), in England from the late 1650s.

Opposition to dogmatism and speculation was focused on the Galenists who, as the polemicist Marchamont Nedham claimed:

- in a manner after their own Phantasie, framed the Art of Physick into a general Method, after the fashion of some Speculative Science; and so by this means, a copious form of Doctrin, specious enough, but fallacious and instable, was built’ (Medela medicinae, London, 1665, p. 238)

By contrast, there was a strong emphasis on observation and experiment amongst the chymical physicians. George Starkey, the American émigré, whose chymical medicine had a profound influence on Boyle, but who died of the plague in 1665, opens his Nature’s Explication (London, 1657, p. 1), which is dedicated to Boyle, with the following claim:

- What profit is there of curious speculations, which doe not lead to real experiments? to what end serves Theorie, if not appplicable unto practice.

In 1665 in his Galeno-Pale, the chymical physician George Thomson entitled his tenth chapter ‘An Expostulation why the Dogmatists will not come to the touchstone of true Experience’. Thomson explicitly identifies himself as an experimental physician in his Misochymias elenchos … with an assertion of experimental philosophy, London, 1671.

Moreover, very early in the life of the Royal Society there were calls for natural histories of disease. Christopher Wren and Robert Boyle both set this as a desideratum for medicine and saw it as part of the broader program of Baconian natural history that the Society was pursuing. And in the 1660s Bacon’s method of natural history was affirmed and practised by physicians of the likes of Timothy Clarke and Daniel Coxe. Clarke had been involved in the exciting blood transfusion experiments of the mid-1660s and Coxe was a chymical physician, who even tried, though without much success, to get Sydenham interested in chymistry.

It is pretty clear then that Sydenham was not the first English physician to adopt and employ the new method of the experimental philosophers. Indeed, from the time that it first emerged, the experimental philosophy was applied in medicine. Why is it then, that Sydenham and not Clarke, Coxe or Thomson is hailed as the English Hippocrates? Part of the answer must lie in the fact that the chymical physicians were decimated by the plague in 1665, for they stayed in London in the belief that they could cure it. Part of the answer also lies in the politics of Restoration medicine and the mixed fortunes of the College of Physicians and its vexed relations with the Royal Society. And yet there must have been other factors involved. I have documented the emergence of Sydenham’s posthumous reputation in ‘The creation of the English Hippocrates’ which appears in Medical History this month. But I am not satisfied that I have a full understanding of the Sydenham phenomenon and I look forward to hearing insights that others might have.