Francis Bampfield: an early critic of experimental philosophy

Peter Anstey writes…

In a recent article Peter Harrison has drawn our attention to the phenomenon of experimental Christianity in seventeenth-century England (‘Experimental religion and experimental science in early modern England’, Intellectual History Review, 21 (2011)). In this post I would like to take up where Harrison left off and discuss one proponent of experimental religion whom Harrison does not mention, namely Francis Bampfield (1614–1684). Bampfield provides an interesting case study because while he was a promoter of experimental Christianity, he was also a harsh critic of the new experimental natural philosophy.

In two works from 1677, All in One and SABBATIKH, Bampfield lays out his case against experimental natural philosophy. In his view the source of all useful and certain knowledge is the Scriptures.

Practical Christianity, and experimental Religion is the highest Science, and the noblest Art, and the most honourable Profession, which gives light to all inferiour knowledges, and would admit into the Royalest Society, and draw nearest in resemblance and conformity, to the glorified Fellowship in the Heavenly College above, where their knowledge is perfected in visional intuitive light. Here is the prime Truth, the original Verity, as to the manifestativeness of it in legible visible ingravings, which would carry progressively into other Learning contained therein: all here is reducible to practice and use, to life and conversation; here existences and realilties are contemplated and proved, not mere Ideas and conceits speculated as elsewhere. (All in One, p. 12)

It is the mere ideas and conceits of the new experimental philosophy of the Royal Society, or the Fellows of Gresham College, that Bampfield is concerned to expose:

How many thousands have by their wandring after such misguiders left and lost their way in the dark, where their Souls have been filled with troublesome doubts, and with tormenting fears, exposing them to violent temptations of Atheism and Unbelief? and what wonder, that it is thus with the Scholar, when some of the learnedest of the Masters themselves have resolved upon this, as the conclusion of all their knowledge, that, All things are matter of doubtful questionings, and are intricated with knotty difficulties, and do pass into amazing uncertainties, and resolve into cosmical suspicions? And this, not only is the deliberate Judgement of particular Virtuoso’s in our day, but has been the publick determination of an whole University. (All in one, p. 3)

What are these ‘knotty difficulties’ that pass into ‘amazing uncertainties’ resolving into ‘cosmical suspicions’? The alert reader will no doubt see here a direct allusion to Robert Boyle’s Tracts of 1670 in which he discusses cosmical qualities that seem to have ‘such a degree of probability, as is want to be thought sufficient to Physicall Discourses’ (Works of Robert Boyle, eds Hunter and Davis, London, 1999–2000, 6, p. 303). Boyle appended to his essay on cosmical qualities another on cosmical suspicions which contains just the sort of speculative reflections that Bampfield is alluding to here. (As far as I can determine, Boyle’s is the first work in English that uses the term ‘cosmical suspicions’.) That Bampfield was a close reader of Boyle’s writings comes out in a later passage which I quote in extenso:

There is an honourable Virtuosus, who has travelled far in Natures way, and has made some of the deepest inquiries into Experimental, Corpuscular, or Mechanical Philosophy, that in the requisites of a good Hypothesis amongst others of them, doth make this to be one of its conditions, that it fairly comport not only with all other truths, but with all other Phaenomena of Nature, as well as those ’tis fram’d to explicate, and that, not only none of the Phaenomena of Nature, which are already taken notice of do contradict it at the present, but that, no Phaenomena that may be hereafter discovered, shall do it for the future. Let it therefore from hence be considered, whether seeing, that History of Nature, which is but of human indagation and compiling, is so incomplete and uncertain, and many things may be discovered in after-times by industry, or in some other way by providential dispensing, which are not now so much as dreamed of, and which may yet overthrow Doctrines speciously enough accommodated to the Observations, that have been hitherto made (as is by himself fore-seen and acknowledged) whether now, the only prevention and remedy in this case (which is otherwise so full of just fears, of real doubts, of endless dissatisfaction, and of perplexing difficulties) be not, to bring all sorts of necessary knowledges to the Pan-sophie, the Alness of Wisdom, in the Scriptures of Truth, where none of the forementioned Scriptures have any ground to set their foot on, in regard that Word-Revelations about Natures Secrets, are the unerring products of infinite Wisdom, and of universal fore seeingness, which are always uniform and the same, in their well-established order, and stated ordinary course without any variation, by an unchangeable Law of the All-knowing Truthful Creator, and Governour, and Redeemer. (All in One, pp. 56-7)

Bampfield is, of course, referring to Boyle’s Excellency of Theology (Works, 8, p. 89) and while he is cautious not to be overtly critical of Boyle here, the thrust of his comments is to undermine the epistemic status of the experimental philosophy, calling it ‘incomplete and uncertain’. For, as he says in his sequel SABBATIKH:

the unscriptural way they take in their researches into natural Histories and experimental Philosophy, will never so attain its useful end for the true advance of profitable Learning, till more studied in the Book of Scriptures, and suiting all experiments unto this word-knowledge. (SABBATIKH, p. 53)

It is ‘word knowledge’ and not knowledge of the world that Bampfield is defending. What Boyle himself made of all of this, if it even came to his attention, we will never know. He never mentions Bampfield in any of his works or correspondence.

Experimental Philosophy in Spain Part II

Juan Gomez writes…

In my previous post I reviewed some texts from Spanish authors in the 17th century to show that, contrary to common opinion, intellectuals in the Iberian Peninsula were in fact acquainted with the progress and achievements of the new experimental philosophy. They did not just know of it, but actually advocated its application and called for the rejection of the old method of the scholastics. In this post I will conclude this overview of the ESD in Spain by looking at the work of the Novatores in the eighteenth century.

The texts we examined in my last post were both written by physicians. In the eighteenth century medicine remained as the forum for the promotion of experimental philosophy. The first author I will examine is Doctor Martín Martínez. He was a physician and professor of anatomy in Madrid, and royal physican to Phillip V. Besides a number of medical writings, in 1730 he published Filosofía Escéptica which consisted in a dialogue between an Aristotlian, a Cartesian, a Gassendist, and a Sceptic. In the preliminaries to this book he tells us that

- The spirit of this book is to give to the Curious Romantics an idea of the most famous philosophies that today run through Europe, relegating that Aristotle just for theological studies.

Even in the 1730’s books in Spain still included a statement of approval made by a priest or friar that confirmed that there was nothing in the book to be censured. The censorship for Filosofía Escéptica was written by Friar Agustín Sanchez and in it we find a statement in the spirit of experimental philosophy. Speaking of the account Martínez gives of the Aristotelian, Cartesian, and Gassendist positions he tells us that the Doctor

- Is determined not to follow any of them, but is inclined towards what he judges more plausible; he does not believe in what experience cannot confirm, based on the fact that words cannot reach the truth of physical and material things, nor their natures and properties; what experience cannot testify, and persuade, cannot be known by words.

Martínez begins his dialogue by giving a brief history of philosophy in Spain, blaming the Arabians for the introduction of Aristotelian philosophy,

- From which that contentious and vociferous philosophy we call Scholastic, as opposed to Experimental, has been derived.

A few lines later Martínez comments that he shares the same opinion held by Bacon:

- The most judicious Verulam also held, that of all the philosophies that have been invented, and received, so many were but fables, and Comical Scenes, each of them making the world to their liking, amassing the Elements to the measure of their palate, and arbitrarily establishing hypotheses as difficult to believe, as they are to prove.

In the case of Martín Martínez we can see the experimental philosophy and the rejection of mere speculation clearly represented. But to show that this was not an isolated case I turn now to another doctor, Andrés Piquer. Out of all the Novatores that practices medicine, Piquer was the one that published most on other topics. He published a book on logic, one on moral philosophy, and one on physics. This last one was published in 1745 under the title Física Moderna Racional, y Experimental (Modern Physics, Rational and Experimental). Piquer begins this book by giving some preliminaries about the state and history of physics and the method to follow. In his historical account he tells us that

- Physics was wrongly cultivated for many centuries, until Francis Bacon Lord Verulam, Great Chancellor of England, towards the end of the sixteenth century, started to renew it, freeing it form the superfluity of reasoning, and manifesting, that the true way to advance in it is through the path of experience.

Speaking about the proper method Piquer sets up a distinction that illustrates the presence of the ESD (in some form) in Spain:

- Modern physicists, are either Systematic, or Experimental. The former explain nature according to some system; the latter discover it through the way of experience. The Systematic form in the imagination some idea, or drawing of the principal parts of the World, of its connections, and mutual correspondence; and holding such idea, that sometimes is strictly willed, as a principle, and foundation of their Philosophy, try to explain everything that occurs in the universe according to it. This has been done by Descartes, and Newton. The Experimental work to collect many experiments, combine them, and use them as the basis of their reasonings. This is how Robert Boyle, Boerhaave, and many other philosophers of these times treat physics.

One of the interesting features of this passage is that Piquer groups Descartes and Newton together under systematic philosophers! However, I don’t have the space or time to discuss this very interesting issue in this post, but Piquer’s distinction between systematic and experimental is something worth looking into. For now, I believe I have provided some very interesting passages from early modern Spanish authors that show that they were acquainted with experimental philosophy and opposed and rejected mere speculation.

N.B. The English translation of the quotes presented here is mine

Locke’s swallows

Peter Anstey writes…

John Locke’s commitment to the experimental philosophy was extraordinary. In the 1690s, arguably the busiest decade of his life, Locke continued to make daily detailed records of the prevailing weather conditions at Oates, the house of Francis Masham where he resided from 1691.

Each day he would enter the day of the month, the hour, the temperature, barometric pressure, humidity, wind direction and speed, and the overall weather conditions. Sometimes he recorded three or four sets of data within a single day. Of course, Locke was not the only one in England who was collecting such data. He was merely a small part in a larger loosely connected project that aimed to construct a natural history of the air. The inspiration here was his mentor Robert Boyle whose A General History of the Air Locke had seen through the press in 1692 after Boyle’s death. Indeed Locke included a set of his own weather records from the 1660s in that work and perhaps it was the self-confessed incomplete nature of Boyle’s history that spurred Locke on to resume his weather charts in December 1691 (the very month in which Boyle died). The incompleteness of Boyle’s history is also the explanation of the fact that Locke had his own copy of the work interleaved and began to add new observations on the air.

One particularly interesting set of records is that for the month of September 1694. Here are the readings for the 4th of that month:

Day Hour Temp Barom Hygrom Wind Weather

| 4 | ∙9 | 5o— | 15. | 2436 | WS 3 | covered, a shower at 21 |

| 24 | 1 ∙ 7 | 29∙10. | 2233 | very fair |

The small dot to the left of the hour indicates that the first reading was made around 9.45am. There was no standard of temperature in Locke’s day, so he provides a relative reading of 5 marks above the zero mark, which was set at temperate rather then freezing. The morning wind from the WSW was evidently quite strong: Locke’s scale is from 0 to 4. And he was up late recording that there was a rain shower at 9pm and taking another set of readings at midnight. (It is interesting to note too that he used a 24-hour clock and records made at midnight are not uncommon.)

After this entry, Locke makes the following observation:

SWALLOWS. No Swallow or Martins this day plying about the house or Moat as they used to be but every now & then 3 or 4 or more appeared & after 2 or 3 turns were gone again out of sight they generally flew very high and seemed to be passengers & to take their course southward as far as I could observe whether they were plying about the house yesterday or not I did not observe.

Then on the 19th of the month he reflects back on the swallows:

SWALLOWS The observation made 4° Sept will need some further experiments to confirm it. It being hard to take notice of their flight so as to be sure they doe not return again. But this I am certain that after that day neither SWALLOWS nor Martins were so many nor so busy as before. But yet some of them though not so frequent were to be seen till the 19th & then I went to London.

Notice the talk of the need for further experiments. Here, within a project for the systematic collection of data for a Baconian natural history, a project that involves the daily use of newly invented meteorological instruments, Locke makes a further observation and conceives of it in terms of the application of the experimental method.

So thorough are Locke’s records that, by his own admission, ‘there seldom happen’d any Rain, Snow, or other remarkable change, which I did not set down’. And what was it all for? He told Hans Sloane that with enough meteorological data ‘many things relating to the Air, Winds, Health, Fruitfulness, &c. might by a sagacious man be collected from them, and several Rules and Observations concerning the extent of Winds and Rains, &c. be in time establish’d to the great advantage of Mankind.’

Shapiro and Newton on Experimental Philosophy

Kirsten Walsh writes…

In a recent post, I discussed Alan Shapiro’s paper, ‘Newton’s “Experimental Philosophy”‘, where he argues that

- the apparent continuity between Newton’s usage [of the term ‘experimental philosophy’] and that of the early Royal Society is, however, largely an illusion.

I examined his claim that ‘experimental philosophy’ was used as a synonym for ‘mechanical philosophy’ by the early Royal Society, whereas for Newton, the two terms had different meanings.

Today I’ll address another argument Shapiro makes in that paper.

Shapiro claims that Newton’s adoption of the experimental philosophy occurred quite late – while preparing the 2nd edition of Principia, published in 1713. To support this claim, Shapiro argues that, in the 1713 edition of Principia, Newton uses the term ‘experimental philosophy’ for the first time in public. Moreover, the methodology Newton describes in this context is very different to the methodology he describes in his early optical papers. Shapiro writes:

- At this time [1675] for Newton confirmation is by mathematical demonstration and secondarily – only if you think it is worth the bother – by experiment. He clearly believed that a mathematical deductive approach would lead to great certainty and that experiment could provide the requisite certain foundations for such a science, but until the eighteenth century he did not assign experiment a primary place in his methodology.

If Newton’s ‘experimental philosophy’ is a late development, then this provides additional support for Shapiro’s claim that Newton’s experimental philosophy is not continuous with the methodology of his predecessors, the early members of the Royal Society.

In this post, I’ll argue that (1) experiment is a prominent theme in Newton’s methodological statements between 1672 and 1713, and (2) Newton’s methodology has features that suggest the influence of the early Royal Society.

1. Experiment is a prominent theme between 1672 and 1713

There is a strong experimental theme in Newton’s early optical papers (1672-1675). For example, he says:

- the proper Method for inquiring after the properties of things is to deduce them from Experiments.

And:

- I drew up a series of such Experiments on designe to reduce the Theory of colours to Propositions & prove each Proposition from one or more of those Experiments by the assistance of common notions set down in the form of Definitions & Axioms in imitation of the Method by which Mathematicians are wont to prove their doctrines.

And:

- Now the evidence by which I asserted the Propositions of colours is in the next words expressed to be from Experiments & so but Physicall: Whence the Propositions themselves can be esteemed no more then Physicall Principles of a Science.

In the opening paragraph of De Gravitatione (date of composition unknown), Newton says:

- in order, moreover, that … the certainty of its principles perhaps be confirmed, I shall not be reluctant to illustrate the propositions abundantly from experiments as well…

In the 1st edition of Principia (1686), Newton says:

- The principles I have set forth are accepted by mathematicians and confirmed by experiments of many kinds.

And in the 1st edition of Opticks (1704), Newton says:

- My Design in this Book is not to explain the Properties of Light by Hypotheses, but to propose and prove them by Reason and Experiments…

Experiment doesn’t seem secondary to me!

2. Newton’s methodology suggests the influence of the early Royal Society

As we have said before, the Royal Society adopted the experimental philosophy in a Baconian form – according to the Baconian method of natural history. There is good evidence that Newton was familiar with the work of the Royal Society by the time he wrote his first optical paper in 1672: his notebooks show that he took notes from many issues of the Philosophical Transactions and he took careful notes on Boyle’s work. Newton never adopted the Baconian method of natural history. However, other features of Newton’s methodology suggest the influence of the early Royal Society. For example, he made use of queries, he adopted the familiar distinction between theory and hypothesis, he was concerned with experiments, and he rejected speculation and speculative systems.

Shapiro notices that Newton rejected speculative systems, but fails to recognise that Newton wasn’t the first member of the Royal Society to take this stance. On this blog we have provided ample evidence that the early members of the Royal Society railed against speculation. Newton’s anti-speculation and anti-hypothetical stance, while extreme, was still inside the spectrum of acceptable experimental positions. Consider this passage from Hooke’s Micrographa, addressed to the Royal Society:

- The Rules YOU have prescrib’d YOUR selves in YOUR Philosophical Progress do seem the best that have ever yet been practis’d. And particularly that of avoiding Dogmatizing, and the espousal of any Hypothesis not sufficiently grounded and confirm’d by Experiments. This way seems the most excellent, and may preserve both Philosophy and Natural History from its former Corruptions.

Whether or not Newton explicitly identified himself as such, we have good reason to think that Newton’s first optical paper in 1672 was written by an experimental philosopher.

Experimental Philosophy in Spain

Juan Gomez writes…

We have presented plenty of evidence in this blog to support our claim that the experimental/speculative distinction (ESD) provides the best terms of reference to interpret early modern philosophy. One of the worries we’ve had was that the ESD seemed to be a strictly British phenomenon. However as we have shown in this blog, the distinction is also present in the work of philosophers in other parts of Europe (France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands). In this post I want to further expand on the use of the ESD in continental Europe by exploring the case of Spain. It is a particularly interesting case due to the influence the church (the Inquisition in particular) had on the development of the country. Many of the influential books in natural philosophy (like the work of Descartes and Bacon) were banned by the Catholic Church, which also meant that the “new philosophy” was not taught at universities. Foreigners believed that the Spanish were not at all acquainted with the new philosophy and had the image that Spain was far behind the rest of Europe. Francis Willughby had travelled with his friend and botanist John Ray through Europe and decided to return via Spain in 1666. His opinion of the “backwardness of the country” was published posthumously in a book where Ray and Willughby’s travels are documented (Observations, Topographical, Moral and Physical…) (1673)

- I heard a Professor read Logick. The scholars are sufficiently insolent and very disputatious… None of them understood any thing about the New Philosophy, or had so much as heard of it. None of the new books to be found in any of their Bookseller shops: In a word the University of Valencia is just where our universities were 100 years ago… In all kind of good learning the Spaniards are behind the rest of Europe, understanding nothing at all but a little of the old wrangling Philosophy and School-divinity.

However, Willughby’s comment is not accurate. There were several circles and professors that not only knew about the “new philosophy” but actually promoted it and applied it in their works. The first field that vouched for the experimental method was medicine, but in the eighteenth century this philosophy expanded to all areas. As early as 1650 there are references to Bacon and to the new philosophy in Sebastian Izquierdo’s Pharus Scientiarium, a book about the proper way to do science. At the end of the century we find clear expression of the praise for the method of the new philosophy associated with Bacon. The following quote is from Juan de Cabriada’s 1687 Carta Philosophica (English translation is mine):

- Es regla asentada, y máxima cierta en toda medicina, que ninguna cosa se ha de admitir por verdad en ella, ni en el conocimiento de las cosas naturales, sino es aquello, que ha mostrado la experiencia mediante los sentidos exteriores: Asimismo es cierto, que el médico ha de estar instruido en tres géneros de observaciones, y experimentos, como son: anatómicos, prácticos, y chymicos.

- It is an established rule, and true maxim in all of medicine, and in the knowledge of natural things, that nothing is to be admitted as true, if it is not what has been shown by experience through the external senses: it is also certain, that the physician must be instructed in three kinds of observations, and experiments: anatomical, practical, and chymical.

The emphasis on experience and observation is clear, and de Cabriada goes on to discuss how the discovery of the circulation of the blood by William Harvey is of great advantage to science and opposes it to the Galenic theory of the blood used by the scholastics.

Diego Mateo Zapata, a doctor trained in Galenic medicine, actually published against de Cabriada and his method, but in 1690 he had embraced the new science and discarded the Galenic method. Zapata became one of the main promoters of the new philosophy in Spain. In 1701 he published his Crisis Medica, dedicated to the newly established Regia Sociedad Médica de Sevilla (Royal Medical Society of Sevilla). He tells us that the aim of the society is to show medicine

- In its full splendor, which it deserves, getting rid of the shadows that either make it stop at the theoretical, or don’t let it shine in the practical with such experimental clarity, of which it can’t be doubted if it is shadow or light… This society is useful, because it does not rely on the adornments of speech, or on authority, but on the examinations of experience… nothing is more worthy of laughter, of tears, than a drawn curation, like those the Prince (Galen) achieved through the lines of speculation, tinged only with the colors of his own opinion, regardless of whether it was shown to be contrary to experience, like the ancient doctors did.

Zapata continued the attack on the scholastics and speculative philosophy and in 1745 a posthumous publication came out titled Ocaso de las formas Aristotelicas (Twilight of Aristotelian Forms). Zapata and de Cabriada are just two examples that show that Spain was not as backwards as Willughby thought. Further, Spanish intellectuals were very much acquainted with the new philosophy and its contribution to science. Both thinkers that I have quoted today were identified by the term ‘Novatores’ that was used at the time to refer to those thinkers that opposed the scholastic way of doing philosophy. In my next post I will examine the work of the Novatores in the eighteenth century.

Teaching Experimental Philosophy in Eighteenth-century Germany: Christoph Meiners

Alberto Vanzo writes…

- Since I am convinced that experience and history are the sole authentic sources of knowledge in all sciences, apart from pure mathematics, the choice and order of the works that I recommend to the young friends of wisdom must necessarily deviate from the works that would be recommended by the men for whom pure reason or pure intellect appear to be the most reliable guides and teachers in philosophy.

These are the words with which Christoph Meiners, a German experimental philosopher, introduced his reading tips for young students in the Preface to his Foundations of Psychology, a manual that he published in 1786. In this post I will draw from Meiners’ Preface to highlight his views on the relation between natural science, philosophy, and psychology and his reading tips for young students of psychology.

Natural science, philosophy, and psychology

We have already explained in his blog how experimental philosophy saw the light as a natural-philosophical methodology and was extended to psychology by Locke and Hume and moral philosophy by Scottish thinkers. Meiners is one of the many German authors who applied the Baconian method of natural history to the field of psychology. Interestingly, in Meiners’ preface, empirical or experimental psychology expels natural history and physics [Naturkunde or Physik] from the field of philosophy. Meiners follows Hume in defining philosophy as “a science of man or a sum of cognitions that inquires into human nature not only insofar as man senses, thinks and talks, desires and hates, but also insofar as he, through his feeling and thinking, desiring and acting, becomes or makes others happier or unhappier in manifold domestic and civil contexts.” Since natural history and the experimental study of nature are not specifically about man, Meiners might have reason to deny that, as a whole, they are parts of philosophy as he understands it.

This is precisely what he does. Meiners suggest that, if one wanted to include natural history and the study of nature within philosophy, one should also include medicine and its branches within philosophy. This would have two unacceptable consequences. First, it would make the domain of philosophy so enormously large “that no human mind could encompass it”. Second, one would lose “the whole purpose for which one orders together certain sums of cognitions into sciences” distinct from one another. For Meiners, philosophy on the one hand, natural science and natural history on the other, are distinct sciences. By distinguishing the study of nature from the study of man, Meiners draws a division between natural science and philosophy that would become common only in the nineteenth century. (If you know of anyone else who explicitly denied that natural science is part of philosophy before Meiners, please get in touch.)

Meiners distinguishes between theoretical and practical philosophy. “Theoretical [philosophy] studies man preeminently as a sensing, thinking and talking being”. And Meiners “designate[s] the theory of man […], considered as a sensing, thinking, and talking creature, with the name of doctrine of the soul or psychology”. Theoretical philosophy is empirical psychology. Predictably, practical philosophy should unfold naturalistically on the foundations of empirical psychology. To Meiners, philosophy is experimental philosophy and its core is Humean empirical psychology.

Meiners’ Reading Tips

Given Meiners’ outlook, it is unsurprising that he advises young students to read works like Bonnet’s Essay de Psychologie, Condillac’s Traité des sensations, Beattie’s Philosophical Essays and Locke’s Essay, which “must remain the principal book for students of the soul”.

Somewhat surprisingly, Meiners also recommends the largely Wolffian logic of Herman Samuel Reimarus and Leibniz’s New Essays, to be read alongside Locke’s Essay. But the main reason why his students should read the New Essays is to better know the enemy. From the New Essays,

- one will not only learn the still remarkable hypotheses of one of the greatest philosophers, but also at the same time the principles and doctrine of all those men who choose not experience and history, but so-called pure reason as their first guide in philosophy.

As the reference to pure reason suggests, Meiners recommends his young students to read Leibniz to better understand Kant. He is well aware that Kantianism represented the major threat to his Humean outlook. By grouping together Kant and Leibniz as speculative enemies of Humean experimental philosophy, Meiners was employing the experimental/speculative distinction that Kant and his followers would soon eclipse and replace with the historiographical distinction between empiricism and rationalism.

Teaching experimental philosophy: the case of George Adams Jr

Peter Anstey writes…

Around 100 works were published in the eighteenth century that bore the term ‘Experimental Philosophy’ in their title. Of these more than 80 were works designed for the teaching of experimental philosophy. In my last post I examined one of the earliest of these course books, J. T. Desaguliers’ Lectures of Experimental Philosophy of 1719. In this post we turn to one of the last of the course books published in the century, namely George Adams Junior’s 5 volume Lectures on Natural and Experimental Philososphy, first published in 1794.

Before turning to the contents of this work, however, it is worth noting that 48 of the 100 works, that is nearly half of them, were published in the last 15 years of the century. So Adams’ volumes were very much part of a publishing trend and they can only be properly understood by a comparison with the spate of other publications around them.

Nevertheless, these volumes contain some interesting surprises. The first thing to note is that Adams takes a decidedly historical approach to his subject, describing the origins of, say, experiments on air pressure with Torricelli and Pascal and tracing them through Boyle and others. These historical surveys serve to highlight just how important developments in seventeenth-century experimental philosophy were to those writing toward the end of the following century.

The second thing to note is the surprisingly high profile of Francis Bacon and Robert Boyle. The many references to Boyle and the esteem in which Adams clearly held him is perhaps explained in part by the fact that Adams’ work has a theological agenda similar that of some of Boyle’s natural philosophical output. The subtitle to Adams’ book is ‘Describing, in a familiar and easy manner, the Principal Phenomena of Nature; and Shewing, that they all co-operate in Displaying the Goodness, Wisdom, and Power of God’. However, it’s a little over the top when Adams says of Boyle,

- He seems to have been a heavenly spirit in a human form descending from above, to survey the wonders of this lower frame … (vol. 1, p. 10)

This sort of praise is more often associated with Newton in the eighteenth century. Interestingly, Adams seems not to have acquiesced in the over-exuberant praise of Newton. In fact, his view of Newton is far more measured. He does regard Newton as the greatest practitioner of Bacon’s experimental philosophy

- Among those who have pursued the path pointed out in the

Novum Organum

- , Sir Isaac Newton holds the first rank (vol. 2, p. 133)

But when earlier warning against overdependence upon authority he criticizes those who have ‘an implicit faith in the opinions they have adopted’ (vol. 2, p. 104) providing the example of someone who had claimed ‘Newton … is henceforth to be considered as our only sure guide and instructor’.

Thirdly, and most interestingly, Adams includes a 40-page chapter on ‘On the method of reasoning in natural philosophy’ and here we find an enthusiastic endorsement of Bacon’s method of natural philosophy as developed in his Novum organum of 1620. It contains, among other things, a full exposition of the idols of the mind, though Adams shows no interest in Baconian natural history, alluding to it only once and then in passing (vol. 2, p. 136). It is interesting to note, in conclusion, his allusion to Bacon’s comments on the ‘empirical philosophers’. They are,

- those, who labour with great diligence and accuracy, in a few experiments; and then venture to deduce theories and build up systems, strangely wresting every thing else to these experiments. … the opinions produced by these are more deformed and monstrous than those of the sophistical kind.

There is no evidence of the post-Kantian rationalism–empiricism distinction here!

Conflating the Experimental and Mechanical Philosophies

Kirsten Walsh writes…

Recently I read Alan Shapiro’s paper, ‘Newton’s “Experimental Philosophy”’, in which he argues that

- the apparent continuity between Newton’s usage [of the term ‘experimental philosophy’] and that of the early Royal Society is, however, largely an illusion.

To support this claim, Shapiro argues that, whereas ‘experimental philosophy’ was used as a synonym for ‘mechanical philosophy’ by the early Royal Society, for Newton, the two terms had different meanings. This is demonstrated by the fact that Newton adopted the experimental philosophy, but not the mechanical philosophy.

Shapiro explains that the mechanical philosophy is characterised by adherence to some or all of the following theses:

- the world and its components behave like a machine; or, more strongly, the world can be described solely by the mathematical laws of mechanics; all causation is by contact action so that the immaterial, spiritual agents are banished; matter is composed of invisible corpuscles; and hypotheses about the properties and motions of these invisible corpuscles may be formulated to explain visible effects.

Here Shapiro is conflating mechanism and corpuscularianism. However, Peter Anstey explains in his recent book, John Locke and Natural Philosophy, that these are distinct (but related) philosophies. The leading idea of the mechanical philosophy is that natural phenomena should be explained by analogy with the functioning of machines. The corpuscularian philosophy is primarily a philosophy about the underlying nature of matter, whereby explanations of natural phenomena are constrained by appeal to the invisible corpuscles which constitute all material bodies. Thus, the former is a theory of explanation; the latter, a theory of matter. There is a significant amount of overlap between the mechanical and corpuscularian philosophies, for example the focus on shape, size, motion and texture. But, they are not interchangeable. For example, Anstey points out that it wasn’t the case that everyone who held a corpuscularian theory of matter was a mechanical philosopher.

In contrast, the experimental philosophy emphasises that we can only acquire knowledge of nature by first accumulating observations and experiments and then turning to theory and hypotheses. Thus, the experimental philosophy is a theory of method, which can be viewed as placing epistemic constraints on philosophical endeavours, as opposed to the explanatory constraints of the mechanical philosophy, or the ontological constraints of the corpuscularian philosophy. So, at least notionally, these are three distinct philosophical positions.

Shapiro argues that, in practice, the early Royal Society didn’t distinguish between these philosophical positions. As evidence, he cites a passage from the preface to Robert Hooke’s Micrographia in which Hooke runs together “the real, the mechanical, the experimental philosophy”. But if we look at Hooke’s other work for uses of the term ‘mechanical’, we find that he can and does distinguish the mechanical from the experimental.

When Hooke explicitly discusses experimental philosophy, he emphasises the importance of constructing natural histories. For example, in his ‘General Scheme’, where he sets out his “Method of Improving Natural Philosophy”, Hooke explains that the best way to proceed is according to the Baconian method of natural history. He says there are three “ways of discovering the Properties and Powers [of bodies]”:

- I. By the Help of the Naked Senses.

- II. By the Senses assisted with Instruments, and arm’d with Engines.

- III. By Induction, or comparing the collected Observations, by the two preceding Helps, and ratiocinating from them.

When he discusses III, Hooke explains that an understanding of mathematics and mechanics “will most assist the Mind in making, examining, and ratiocinating from Experiments”:

- Mechanicks also being partly Physical, and partly Mathematical, do bring the Mind more closely to the business it designs, and shews it a Pattern of Demonstration, in Physical Operations, manifests the possible Ways, how Powers may act in the moving resisting Bodies: Gives a Scheme of the Laws and Rules of Motion, and as it were enters the Mind into a Method of accurate and demonstrative Inquiry and Examination of Physical Operations. For though the Operations of Nature are more secret and abstruse; and hid from our discerning, or discovering of them, than those more gross and obvious ones of Engines, yet it seems most probable, by the Effects and Circumstances; that most of them may be as capable of Demonstration and Reduction to a certain Rule, as the Operations of Mechanicks or Arts.

Later in the same discussion, Hooke enumerates the different kinds of observations one should make when constructing natural histories:

- 25ly, To enquire and try how many Mechanical Ways there may be of working on, or altering the Proprieties of several Bodies; such as hammering, pounding, grinding, rowling, steeping, soaking, dissolving, heating, burning, freezing, melting, &c.

Hooke is using the term ‘mechanical’ in (at least) two different senses. In the first sense, the term describes the processes of machines; in the second sense, the term describes manual work. But he conflates neither of these with the experimental philosophy. They are distinct, albeit related, philosophies.

Previously on this blog we have claimed that some features of Newton’s early methodology, for example his early use of queries, suggest that he was influenced by the new experimental philosophy of the early Royal Society. I do not claim that Newton’s experimental philosophy is continuous with the experimental philosophy of the early Royal Society, so I do not take issue with Shapiro’s main claim. But I do take issue with his claim that the ‘mechanical philosophy’ and ‘experimental philosophy’ were considered by the early Royal Society to be synonymous.

Degérando’s Experimental History of Philosophy

Alberto Vanzo writes...

So far, on this blog, we have focused on a philosophical movement and a historiographical tradition. Of course, the movement was experimental philosophy. The historiographical tradition was based on the dichotomy of empiricism and rationalism and was first developed by Kantian and post-Kantian authors, like Reinhold and Tennemann, who did not belong to the movement of experimental philosophy. This post is on a historian who was an adherent of experimental philosophy and who endeavoured to employ its methodology in his history of philosophy. He is Joseph-Marie Degérando, who published a Comparative History of the Philosophical Systems, relatively to the Principles of Human Knowledge in 1804. Interestingly, this text is also influenced by the new post-Kantian historiography based on the rationalism-empiricism distinction.

Degérando intends to apply the method of natural history to the history of philosophy. Natural histories were large structured collections of facts about natural phenomena and they were to form the basis for the identification of theories and principles. Degérando’s history of philosophy is a structured collection of facts about past philosophies which will help us identify which philosophical outlook is the best.

Before starting to collect the facts, we must determine the organizing principles of the collection. Philosophers should

- imitate naturalists, who, before entering into the vast regions of natural history, give us regular and simple nomenclatures and they seek the principle of these nomenclatures in the essential characters of each production.

The “nomenclatures” that form the basis for Degérando’s natural history of past philosophers are three dichotomies: scepticism vs dogmatism, empiricism (or sensualism) vs rational (or speculative or contemplative) philosophy; and materialism vs idealism.

Armed with these nomenclatures, historians of philosophy should free themselves of all prejudices and collect historical facts in an unbiased way. Only after having completed this task should historians start philosophizing. Degérando claims to have ascertained “facts as if” he were “foreign to every opinion” and he has “later established an opinion on the basis of the sole testimony of facts”.

In doing this, Degérando does not aim to write a “simple narrative history, to use Bacon’s expression”, but an “inductive or comparative history that converts the facts into “experiences in the path of human spirit.”

- […] the work that we set out to do can be considered as the essay of a treatise of philosophy, […] a treatise conceived of according to the most cautious, albeit most neglected method, the method of experiences. Hence, we dare to offer this essay as an essay of experimental philosophy.

Degérando is strongly influenced by the post-Kantian historiography of Tennemann and other German historians. Like Tennemann, he focuses on epistemological issues concerning “the certainty of human cognitions”, “their origin” and their reality. Degérando uses the distinction between empiricism and rationalism. Like the Kantians, he criticizes them as two unilateral points of view that should be overcome by a higher philosophical standpoint. This is a form of experimental philosophy that is inspired by Bacon and Condillac and is superior to empiricism which as criticized by German historians. Empiricism stops at the facts. The philosophy of experience “transforms them” and identifies general laws.

- Empiricism does not see anything else than the exterior of the temple of nature; experience enters into its sanctuary. Empiricism is an instinct; experience is an art. Empiricism does not see anything else than phenomena, experience ascends from effects to causes. Empiricism is confined to the present; experience learns the future from the past. Empiricism obeys blindly, experience interrogates with method. Everything is mobile, fugitive for empiricism; experience discovers regular and constant combinations underneath the variable appearances. But what need is there to insist on this distinction? He who opens [a book by] Bacon will see it standing out in every page.

The philosophical upshot of Degérando’s experimental history of philosophy

- is spelled out by Bacon’s words, when he said in his preface to the Advancement of Learning: in this way we believe that we are combining, in a manner that is as stable as legitimate, the empirical and rational methods […]

According to Degérando, experimental philosophy, and not Kant’s Critical philosophy is the true, higher synthesis of empiricism and rationalism.

Teaching Experimental Philosophy: Desaguliers and Boyle

Peter Anstey writes…

According to ECCO there were one hundred books published in the eighteenth century with the term ‘experimental philosophy’ in their title. What is surprising about these books is that the majority of them are courses in or lectures on experimental philosophy: they are pedagogical works rather than works in natural philosophy per se.

According to ECCO there were one hundred books published in the eighteenth century with the term ‘experimental philosophy’ in their title. What is surprising about these books is that the majority of them are courses in or lectures on experimental philosophy: they are pedagogical works rather than works in natural philosophy per se.

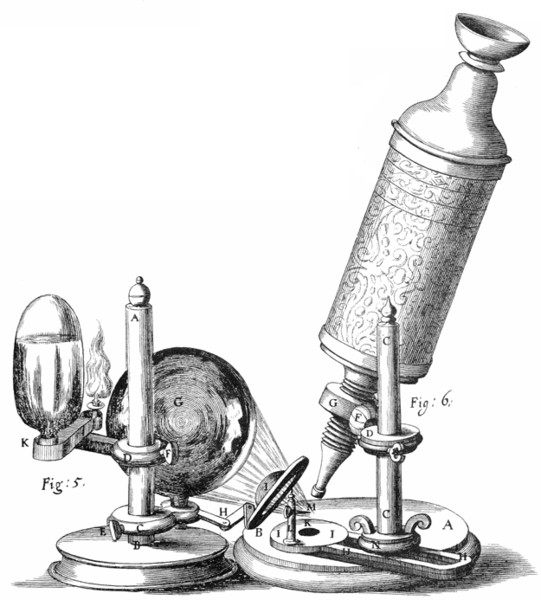

One of the earliest of these works was Lectures of Experimental Philosophy by John Theophilus Desaguliers published in 1719. This work gives the principles of mechanics, hydrostatics and optics, explaining them with descriptions of experiments that had recently been used in these disciplines.

The work is written in the spirit of the experimental philosophy and before Desaguliers launches into his exposition of mechanics, the first discipline that he discusses, he provides the reader with a sketch of the ‘principles’ of natural philosophy. What is interesting is that much of this derives without acknowledgment from Robert Boyle’s Origin of Forms and Qualities (1666/7). Thus, Desaguliers tells us that:

- 1. That the Matter of Natural Bodies is the same; namely, a Substance extended, divisible, and impenetrable. (p. 7)

In Forms and Qualities Boyle says,

- The Matter of all Natural Bodies is the Same, namely a Substance extended and impenetrable. (Works of Robert Boyle, eds Hunter & Davis, 5: 333)

If one were to quibble that Desaguliers has left out the word ‘divisible’, we need only to turn to an earlier passage in Forms and Qualities where Boyle says:

- there is one catholic or universal matter common to all bodies, by which I mean a substance extended, divisible, and impenetrable. (Works, 5: 305)

That Desaguliers read this passage is evident from his third claim:

- 3. That Local Motion is the chief Principle amongst second Causes, and the chief Agent of all that happens in Nature. (p. 8)

Boyle says in the very next paragraph,

- that Local Motion seems to be indeed the Principl amongst Second Causes, and the Grand Agent of all that happens in Nature. (Works, 5: 306)

There are other borrowings from Forms and Qualities, but space prevents me from listing them here. Two points are worth noting, however. First, it is very interesting to see concrete evidence of the influence of Boyle’s Forms and Qualities in the latter years of the second decade of the eighteenth century. Until now there has been little recognition of the impact of this specific work by Boyle, though few would doubt his enormous impact on British experimental philosophy in general.

Second, the text that Desaguliers lifts from Boyle appears in the speculative part of Forms and Qualities: it is speculative natural philosophy and is supported in the ‘historical part’ of that work by experimental observations. There is no sense of this division in Desaguliers’ treatment of these ‘principles’, though he does bring some experimental evidence to bear against the Cartesian materia subtilis. After dismissing various other speculative theories, such as Aristotelianism, Desaguliers simply introduces Boyle’s speculative theory with the following words:

- That Philosophy therefore is the most reasonable, which teaches …