Nicolas Malebranche: Critic of Experimental Philosophy

Peter Anstey writes …

There were many critics of experimental philosophy in its early years. On this blog we have discussed the criticisms of Margaret Cavendish and Francis Bampfield, both of whom were English, and G. W. Leibniz, who was German. In this post we examine the views of the French philosopher Nicolas Malebranche who was highly critical of experimental philosophy too.

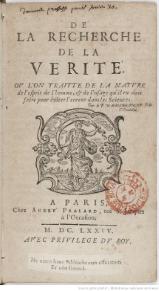

In the first edition of his The Search After Truth of 1674, Malebranche devotes the last section of Book Two to ‘Those who perform experiments’, and this section appears in all six subsequent editions of the book. (See The Search After Truth, eds T. M. Lennon and P. J. Olscamp, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 159–60.)

He opens his treatment of the subject with some general comments that apply both to chemists and ‘all those who spend their time performing experiments’. Ostensibly, the criticisms are not directed at experimental philosophy per se, but towards experimental philosophers themselves. ‘Do not blame experimental philosophy [philosophie expérimentale]’, says Malebranche; it is the errors of its practitioners that he castigates.

He then proceeds to list seven faults, though ‘there are still many other defects … we do not pretend to cover them all here’ (p. 160).

First, their experiments are normally directed by chance and not by reason.

Second, they are ‘preoccupied with curious and unusual experiments’ rather than beginning with the simplest and building up from there.

Third, they seek out those experiments that will bring them profit, lucriferous experiments, as Bacon would call them.

Fourth, they don’t take enough care to note down ‘all the particular circumstances’ that pertain to the experiment at hand, the time of day, place, quality of the materials, etc.

Fifth, they draw too many conclusions from a single experiment, whereas it’s normally the case that one conclusion can only be drawn from many experiments.

Sixth, they only consider particular effects without ascending to ‘primary notions of things that compose bodies’ (p. 159).

And seventh, they often ‘lack courage and endurance, and give up because of fatigue or expense’ (p. 160).

None of these criticisms seem very serious, after all, it is easy to find exceptions to each one in the experimental practice of experimental philosophers in the 1660s and 1670s. One could hardly accuse Newton’s of being directed by chance in the construction of his experimentum crucis for establishing the heterogeneity of white light, even if his discovery of the oblong form of the spectrum of colours in his first experiment was unexpected or discovered by chance. Nor could one accuse Boyle of giving up on account of fatigue or expense in his air-pump experiments.

Yet the heart of Malebranche’s critique is found in the final paragraph of the section on the causes of the seven defects. He lists three causes: lack of application, misuse of the imagination, and, most importantly, judging the differences and changes among bodies only by sensation (p. 160).

This third cause is Malebranche’s real reservation about, not experimental philosophers, but experimental philosophy itself: for this cause implies an over-reliance on the senses, and by implication, an under-utilisation of reason, and, in particular, reasoning from clear and distinct ideas. The whole of Book One of The Search After Truth is given over to a discussion of the unreliability of the senses. For example, one rule of thumb that he sets out in Chapter 5 is: ‘Never judge by means of the senses as to what things are in themselves …’ (p. 24).

Of course, Malebranche is not averse to appealing to experiments and observations when they reinforce a point he is making (see Book I, chap. 12, pp. 56–7), however, the prioritising of experiment and observation above reasoning from pre-established principles and hypotheses – a central tenet of experimental philosophy – is not one of his epistemic values. Malebranche was opposed to experimental philosophy in principle, and not merely because of the ‘defects’ of its practitioners.

Francis Bampfield: an early critic of experimental philosophy

Peter Anstey writes…

In a recent article Peter Harrison has drawn our attention to the phenomenon of experimental Christianity in seventeenth-century England (‘Experimental religion and experimental science in early modern England’, Intellectual History Review, 21 (2011)). In this post I would like to take up where Harrison left off and discuss one proponent of experimental religion whom Harrison does not mention, namely Francis Bampfield (1614–1684). Bampfield provides an interesting case study because while he was a promoter of experimental Christianity, he was also a harsh critic of the new experimental natural philosophy.

In two works from 1677, All in One and SABBATIKH, Bampfield lays out his case against experimental natural philosophy. In his view the source of all useful and certain knowledge is the Scriptures.

Practical Christianity, and experimental Religion is the highest Science, and the noblest Art, and the most honourable Profession, which gives light to all inferiour knowledges, and would admit into the Royalest Society, and draw nearest in resemblance and conformity, to the glorified Fellowship in the Heavenly College above, where their knowledge is perfected in visional intuitive light. Here is the prime Truth, the original Verity, as to the manifestativeness of it in legible visible ingravings, which would carry progressively into other Learning contained therein: all here is reducible to practice and use, to life and conversation; here existences and realilties are contemplated and proved, not mere Ideas and conceits speculated as elsewhere. (All in One, p. 12)

It is the mere ideas and conceits of the new experimental philosophy of the Royal Society, or the Fellows of Gresham College, that Bampfield is concerned to expose:

How many thousands have by their wandring after such misguiders left and lost their way in the dark, where their Souls have been filled with troublesome doubts, and with tormenting fears, exposing them to violent temptations of Atheism and Unbelief? and what wonder, that it is thus with the Scholar, when some of the learnedest of the Masters themselves have resolved upon this, as the conclusion of all their knowledge, that, All things are matter of doubtful questionings, and are intricated with knotty difficulties, and do pass into amazing uncertainties, and resolve into cosmical suspicions? And this, not only is the deliberate Judgement of particular Virtuoso’s in our day, but has been the publick determination of an whole University. (All in one, p. 3)

What are these ‘knotty difficulties’ that pass into ‘amazing uncertainties’ resolving into ‘cosmical suspicions’? The alert reader will no doubt see here a direct allusion to Robert Boyle’s Tracts of 1670 in which he discusses cosmical qualities that seem to have ‘such a degree of probability, as is want to be thought sufficient to Physicall Discourses’ (Works of Robert Boyle, eds Hunter and Davis, London, 1999–2000, 6, p. 303). Boyle appended to his essay on cosmical qualities another on cosmical suspicions which contains just the sort of speculative reflections that Bampfield is alluding to here. (As far as I can determine, Boyle’s is the first work in English that uses the term ‘cosmical suspicions’.) That Bampfield was a close reader of Boyle’s writings comes out in a later passage which I quote in extenso:

There is an honourable Virtuosus, who has travelled far in Natures way, and has made some of the deepest inquiries into Experimental, Corpuscular, or Mechanical Philosophy, that in the requisites of a good Hypothesis amongst others of them, doth make this to be one of its conditions, that it fairly comport not only with all other truths, but with all other Phaenomena of Nature, as well as those ’tis fram’d to explicate, and that, not only none of the Phaenomena of Nature, which are already taken notice of do contradict it at the present, but that, no Phaenomena that may be hereafter discovered, shall do it for the future. Let it therefore from hence be considered, whether seeing, that History of Nature, which is but of human indagation and compiling, is so incomplete and uncertain, and many things may be discovered in after-times by industry, or in some other way by providential dispensing, which are not now so much as dreamed of, and which may yet overthrow Doctrines speciously enough accommodated to the Observations, that have been hitherto made (as is by himself fore-seen and acknowledged) whether now, the only prevention and remedy in this case (which is otherwise so full of just fears, of real doubts, of endless dissatisfaction, and of perplexing difficulties) be not, to bring all sorts of necessary knowledges to the Pan-sophie, the Alness of Wisdom, in the Scriptures of Truth, where none of the forementioned Scriptures have any ground to set their foot on, in regard that Word-Revelations about Natures Secrets, are the unerring products of infinite Wisdom, and of universal fore seeingness, which are always uniform and the same, in their well-established order, and stated ordinary course without any variation, by an unchangeable Law of the All-knowing Truthful Creator, and Governour, and Redeemer. (All in One, pp. 56-7)

Bampfield is, of course, referring to Boyle’s Excellency of Theology (Works, 8, p. 89) and while he is cautious not to be overtly critical of Boyle here, the thrust of his comments is to undermine the epistemic status of the experimental philosophy, calling it ‘incomplete and uncertain’. For, as he says in his sequel SABBATIKH:

the unscriptural way they take in their researches into natural Histories and experimental Philosophy, will never so attain its useful end for the true advance of profitable Learning, till more studied in the Book of Scriptures, and suiting all experiments unto this word-knowledge. (SABBATIKH, p. 53)

It is ‘word knowledge’ and not knowledge of the world that Bampfield is defending. What Boyle himself made of all of this, if it even came to his attention, we will never know. He never mentions Bampfield in any of his works or correspondence.