Thomas Reid and the dangers of introspection

Juan Gomez writes…

In the upcoming symposium we are hosting here at the University of Otago, I will be giving a paper on the features of the experimental method in moral philosophy (you can read the abstract). One of the salient features of this method was the use of introspection as a tool to access the nature and powers of the human mind. In fact, some Scottish moral philosophers acknowledge introspection as the only way we can get to know the nature of our mind. George Turnbull and David Fordyce were proponents of such claims, as well as Thomas Reid. The latter, in the Introduction to his Inquiry into the Human Mind (1764) draws an analogy with anatomy where he tells us that, in the same way we gain knowledge of the body by dissecting and observing it, we must perform an ‘anatomy of the mind’ to “discover its powers and principles.” The problem is that unlike the anatomist who has multiple bodies to observe, the anatomist of the mind can only look into his own mind:

- It is his own mind only that he can examine with any degree of accuracy and distinctness. This is the only subject he can look into.

Reid notices that this is not good for our experimental inquiry into the human mind, since a general law or rule cannot be deduced from just one subject:

- So that, if a philosopher could delineate to us, distinctly and methodically, all the operations of the thinking principle within him, which no man was ever able to do, this would be only the anatomy of one particular subject; which would be both deficient and erroneous, if applied to human nature in general.

But this obstacle doesn’t persuade Reid to give up introspection (Reid uses the term ‘reflection’) since it is “the only instrument by which we can discern the powers of the mind.” What we have to do is be very careful:

- It must therefore require great caution, and great application of mind, for a man that is grown up in all the prejudices of education, fashion, and philosophy, to unravel his notions and opinions, till he find out the simple and original principles of his constitution… This may be truly called an analysis of the human faculties; and, till this is performed, it is in vain we expect any just system of the original powers and laws of our constitution, and an explication from them to the various phaenomena of human nature.

Scottish moral philosophers were faced with this dilemma. On one hand, in order to access the nature of the human mind, they had to rely on a tool that could only examine and observe one particular mind, making the generalization of the principles discovered impossible; on the other hand, introspection was the only way to access the human mind, since by observing others we cannot gain any knowledge of what goes on in their minds, at least not accurately. The solution, consistent with the spirit of the experimental method, was to focus only on what we can experience and observe, and follow this evidence only as far as it can take us. Therefore as Reid points out, we are to use reflection with

- caution and humility, to avoid error and delusion. The labyrinth may be too intricate, and the thread too fine, to be traced through all its windings; but, if we stop where we can trace it no farther, and secure the ground we have gained, there is no harm done; a quicker eye may in time trace it farther.

These comments by Reid show that even when the problems of relying on introspection were explicitly recognized, the Scottish moral philosophers still used it as their way to access the nature of the human mind. Since introspection was considered to be the only reliable way into the workings of the human mind, they had to be very careful with the use they made of it. This caution was achieved by following the methodology of the experimental method, where they could only go as far as their observations would take them, and their conclusions had to be confirmed by the particular experience of many. But such limits to the conclusions drawn from introspection cast doubt on the status of the exercise of reflection: could introspection really be considered ‘experimental,’ or was the justification given by the moral philosophers (Reid in particular) just a rhetorical device? This is a problem that requires a lot more space than a blog post, but if you have any particular thoughts and comments I am looking forward to receiving and discussing them with you.

Paintings as Experiments in Natural and Moral Philosophy

Juan Gomez writes…

About a month ago I published a post on George Turnbull’s Treatise on ancient Painting. There I briefly commented that Turnbull thought that paintings could work as proper samples or experiments for natural and moral philosophy (understood as the ‘science of man’). I want to expand on this issue in this post.

The whole of Turnbull’s Treatise, as he comments at the beginning of chapter seven, is designed to show the usefulness of the imitative arts for philosophy and education in general. After a recollection of the thoughts of the ancient philosophers on these arts, Turnbull dedicates the last two chapters of the book to sketch the reasons for incorporating the arts in the Liberal education program. This is where paintings can serve as samples or experiments.

To understand the role of paintings, it is necessary to point out a general characteristic of Turnbull’s philosophy. He believed that human beings were made to contemplate and to imitate nature, and their happiness was mainly achieved through these two activities. If we take a look and examine all our faculties and powers, we will see that we are perfectly constituted for the study of nature. We acquire knowledge through the observation of nature, and the desire to imitate it leads us to perform experiments that will enhance our understanding of it.

Nature is also the source for the work of the artist:

- The Artist derives all his Ideas from Nature, and does not make Laws and Connexions agreeably to which he works in order to produce certain Effects, but conforms himself to such as he finds to be necessarily and unchangeably established in Nature. (Treatise on Ancient Painting, p. 137)

From this it follows that the paintings of an artist should represent (imitate) nature as it is in reality, following all its laws. With this in mind Turnbull goes on to tell us that paintings in fact serve as samples or experiments for natural and moral philosophy:

- Philosophy is rightly divided into natural and moral; and in like manner, Pictures are of two Sorts, natural and moral: The former belong to natural, and the other to moral Philosophy. For if we reflect upon the End and Use of Samples or Experiments in Philosophy, it will immediately appear that Pictures are such, or that they must have the same Effect. What are Landscapes and Views of Nature, but Samples of Nature’s visible Beauties, and for that Reason Samples and Experiments in natural Philosophy? And moral Pictures, or such as represent parts of human Life, Men Manners, Affections, and Characters; are they not Samples of moral Nature, or of the Laws and Connexions of the moral World, and therefore Samples or Experiments in moral Philosophy? (Treatise, p. 145)

Since the paintings are supposed to represent nature, it is impossible to appreciate them without comparing them to the original (reality). In this sense paintings will provide us with a proper sample of nature that will enhance our knowledge of it. Turnbull’s theory relies on the artist making exact ‘copies’ of nature, and only then can they serve as proper samples. In the case of natural pictures, he allows two sorts of ‘copies’: either exact representations of nature (like a photograph), or imaginary scenes, as long as they conform to the Laws of Nature. If they are not in these categories, then they shouldn’t be taken as proper samples for the study of nature, and in Turnbull’s case, not even as good works of art. Those works of art that do not imitate nature do not give us the pleasure derived from those that do.

Turnbull prescribes a parallel form of realism for moral paintings. These pictures should depict human nature as it really is, and through them we can gain knowledge of our actions and characters:

- Moral Pictures, as well as moral Poems, are indeed Mirrours in which we may view our inward Features and Complexions, our Tempers and Dispositions, and the various Workings of our Affections. ‘Tis true, the Painter only represents outward Features, Gestures, Airs, and Attitudes; but do not these, by an universal Language, mark the different Affections and Dispositions of the Mind? (Treatise, p. 147)

As long as the sole purpose of the arts is to imitate nature, and all the works follow the laws of nature (even in cases of imaginary scenes), Turnbull can count them as having the same effect ‘real’ samples and experiments have.

Turnbull’s Treatise on Ancient Painting and the Experimental/Speculative Distinction

Juan Gomez writes…

In my previous post on David Fordyce’s thoughts on education, I showed how his speech to students on the commencement of the studies embodies the commitment to the method of the experimental philosophy. This is hardly surprising given that his teacher at Marischal, George Turnbull, expressed the same commitment a year before Fordyce’s speech in his Observations upon Liberal Education (1742). In this post I want to focus on an earlier text, his Treatise on Ancient Painting (1740). In addition to trying to find out “wherein the Excellence of Painting consists,” he wants to show the usefulness of this art and its essential role in education.

Relying heavily on texts by ancient authors, Turnbull claims that painting, and the arts in general, have always been (and should always be) connected to the study of nature. In this sense, pictures or paintings, when they reflect and are created in accordance to the laws of nature, can serve as proper samples for the study of nature. By analogy, moral paintings (which showcase the true excellence of art: Virtue) work as proper samples and ‘experiments’ for the study of human nature. (But the topic of ‘experiments’ in moral philosophy will have to wait a couple of posts, since I’m focusing strictly on the education issue first.)

The ESP distinction can be seen at work in the passages where Turnbull commends the experimental method and rejects speculation. Like he did in his Principles of Moral Philosophy, Turnbull expresses antipathy towards hypotheses and praises an emphasis on experiments and observation as the only true method for acquiring knowledge. When discussing one of the main purposes of travelling (since the Treatise on Ancient Painting was supposed to serve as a guide for young British travelers) he tells us the following:

- The Ancients travelled to see different Countries, and to have thereby Opportunities of making solid Reflexions upon various Governments, Laws, Customs and Policies, and their Effects and Consequences with regard to the Happiness or misery of States, in order to import with them into their own Country, Knowledge founded on Fact and Observation, from which, as from a Treasure of Things new and old, sure and solid Rules and Maxims might be brought forth for their Country’s Benefit on every Emergency. For this is certain, that the real Knowledge of Mankind can no more be acquired by abstract Speculation without studying human Nature itself in its many various Forms and Appearances, than the real Knowledge of the material World by framing imaginary Hypotheses and Theories, without looking into nature itself: And no less variety of Observations is necessary to infer or establish general Rules and Maxims in the one than in the other Philosophy. (Emphasis added)

In the final chapters of the book Turnbull again reminds us about the ‘true philosophy,’ this time leaning on Socrates, Bacon, and Newton for support. Arguing for the unity of natural and moral philosophy in education, Turnbull discusses the pleasure derived from the study of nature:

- Socrates long ago found fault with those pretended Enquirers into Nature, who amused themselves with unmeaning Words, and thought they were more knowing in Nature, because they could give high sounding Names to its various Effects; and did not inquire after the wise and good general Laws of Nature, and the excellent Purposes to which these steadily and unerringly work. My Lord Verulam tells us, that true Philosophy consists in gathering the Knowledge of Nature’s Laws from Experience and Observation. And Sir Isaac Newton hath indeed carried that true Science of Nature to a great height of Perfection… I shall only observe farther on this Head, that if this be the right method of improving and pursuing natural Philosophy, it must necessarily follow, that the Knowledge of the moral World ought likewise to be cultivated in the same manner, and can only be attain’d to by the like Method of enquiry: By investigating the general Laws to which, if there is any order in the moral World, or if it can be the Object of Knowledge, its Effects and Appearances must in like manner be reducible, as those in the corporeal World to theirs […]

As we can see, the works of George Turnbull and David Fordyce show evidence of the use of the ESP distinction in fields outside of natural philosophy. Beyond this, they show that the moral philosophy taught by these gentlemen in Aberdeen in the first half of the eighteenth century was driven by the characteristic attitude of the experimental method, shedding light on the development and roots of the ‘science of man’ in the eighteenth century.

David Fordyce’s advice to students

Juan Gomez writes…

I have mentioned the name ‘David Fordyce’ a couple of times in my previous posts. The influence this thinker had in the second half of the eighteenth century (Benjamin Franklin was impresed by his works, though he mistakenly credited them to Hutcheson) usually goes unnoticed, despite the success of his main works. He is also a very good example of the adoption of the rhetoric and methodology of experimental philosophy in the field of moral philosophy.

Fordyce (1711-1751) studied at Marischal College, Aberdeen, in the 1720s (the same decade George Turnbull was a regent there). He came back to his alma mater in 1742 to become a regent himself. During this period he taught, as most regents did, “all the Sciences, Logics, Metaphysics, Pneumatics, Ethics strictly so called & the Principles of the Law of Nature and Nations with natural and experimental Philosophy.” (David Fordyce to Philip Doddridge, 6 June 1743. Quoted in the Liberty Fund edition of his Elements of Moral Philosophy). This was also the period when he published his main works, the Dialogues Concerning Education (1745) and The Elements of Moral Philosophy (1748). The latter was first published as section nine of Robert Dodsley’s The Preceptor (1748), anonymously, and then published posthumously in 1754. The essay had such a good reception that it was used as the text book for moral philosophy lectures in North American universities, and it was used almost in full (only the conclusion was ommitted) for the entry on moral philosophy of the Encyclopaedia Britannica from its first edition until well into the nineteenth century.

A recent edition of the Elements also includes a speech he gave to his students at the start of the year of lectures on moral philosophy, which is the text I want to focus on. The speech is entitled A brief Account of the Nature, Progress, and Origin of Philosophy delivered by the late Mr. David Fordyce, P. P. Marish. Col: Abdn to his Scholars, before they begun their Philosophical course. Besides the explicit use of the terminology of the experimental method in his Elements (induction, hypotheses, deduction of rules from observation, etc.), his speech shows the traits that characterize the methodology of the experimental philosophy. For example:

- “It is evident that setting aside sovreign instruction, true knowledge must be acquired by slow degrees from experience & observation, & that it will always be proportionate to the largeness & extent of our Experience.”

- “The knowledge then of the nature, laws & connections of things is, as has been observed, Philosophy; and they who apply to the study of these, & from thence deduce rules for the conduct & improvement of human life, are Philosophers. They who consider things as they are or as they exist, & draw right conclusions from thence, are true Philosophers. But they who without regard to fact or nature indulge themselves in framing systems to which they afterwards reduce all appearances, are, notwithstanding their ingenuity & subtilty, to be reckoned only the corrupters & enemies of true learning.”

- “Now there is a natural & proper method of attaining to true knowledge as well as any other accomplishment, which if neglected must occasion error & contradiction. It cannot be too often repeated, that there is no real knowledge, nor any that can answer a valuable End, but what is gathered or Copyed from nature or from things themselves. That the knowledge of Nature is nothing else than the knowledge of facts or realities & their established connections. That no Rules or Precepts of life Can be given or any Scheme of Conduct prescribed, but what must suppose a settled Course of things conducted in a regular uniform manner. That in order to denominate those Rules just, & to render those Schemes successful, the Course of things must be understood & observed. & that all Philosophy, even the most didactic & practical parts of it, must be drawn from the Observation of things or at least resolved into it; Or which is the same thing, that the knowledge of truth is the knowledge of Fact, & whatever Speculations are not reduceable to the one or the other of these are Chimerical, Vague & uncertain.”

The previous are just the most telling quotes, but the whole overview Fordyce gives of the history of philosophy embodies the anti-Aristotelian, anti-hypothetical attitude of the experimental philosophy. Such was the message Fordyce delivered as a regent to his students in the 1740s, highlighting the relevance of the experimental/ speculative distinction, with the former being the only appropriate method for the progress of knowledge.

That’s it for now, but stay tuned to our blog. Pretty soon we will have a guest post by Dr. Gerhard Wiesenfeldt on a topic closely related to Fordyce’s speech: early modern universities and experimental philosophy.

Anti-Newtonianism in moral philosophy?

Juan Gomez writes…

Peter Anstey recently posted a reply to Eric Schliesser’s criticisms of the experimental/speculative distinction we are proposing. Eric posted some comments on this topic in the New APPS: Art, Politics, Philosophy, Science blog, where he expanded his criticisms by presenting a four-fold problem for our distinction. I quote the fourth point of criticism from Eric’s post:

- Fourth, and most important to the history of philosophy, when the “experimental” philosophy was introduced into moral areas (Turnbull, Hume, etc.) it was decidedly Baconian in character, and often quite hostile to Newton (but that story must await more detail later).

I am going to pitch in my reply before Eric gives us more details on this hostility to Newton. In my previous post on the ‘spirit’ of experimental philosophy, I attached a document with some quotes from Turnbull’s Principles of Moral Philosophy that illustrate the opposite of Eric’s claim. The following are just the three most explicit quotes (you can check this document for more of them):

- Account for MORAL, as the great Newton has taught us to explain for NATURAL Appearances, (that is, by reducing them to good general laws) (Epistle dedicatory, i)

- The great Master [Newton], to whose truly marvelous (I had almost said more than human) sagacity and accuracy, we are indebted for all the greater improvements that have been made in Natural Philosophy, after pointing out in the clearest manner, the only way by which we can acquire real knowledge of any part of nature, corporeal or moral, plainly declares, that he looked upon the enlargement Moral Philosophy must needs receive, so soon as Natural Philosophy, in its full extent, being pursued in that only proper method of advancing it, should be brought to any considerable degree of perfection, to be the principal advantage mankind and human society would then reap from such science. (Preface, iii)

- It was by this important, comprehensive hint [Newton’s], I was led long ago to apply myself to the study of the human mind in the same way as to that of the human body, or any other part of Natural Philosophy: that is, to try whether due enquiry into moral nature would not soon enable us to account for moral, as the best of Philosophers teaches us to explain natural phenomena. (Preface, iii)

One last thought, and a preview of a post in the near future, regarding Eric’s comments: David Fordyce, regent at Marischal College for 10 years (1741-1751), studied in the same college in the 1720’s when Turnbull was a regent. His posthumous publication The Elements of Moral Philosophy might fall under Eric’s description of being ‘Baconian in character,’ but there is certainly no hostility to Newton, and it fits in nicely with our description of experimental philosophy. I leave you with a passage from Fordyce’s book. It is interesting to mention here that parts of Fordyce’s book were used by William Smellie’s for the entry on moral philosophy of his first edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, and were maintained in the following editions for decades.

- Moral Philosophy has this in common with Natural Philosophy, that it appeals to Nature or Fact; depends on Observation, and builds its Reasonings on plain uncontroverted Experiments, or upon the fullest Induction of Particulars of which the Subject will admit. We must observe, in both these Sciences, Quid faciat & ferat Natura; how Nature is affected, and what her Conduct is in such and such Circumstances. Or in other words, we must collect the Phaenomena, or Appearances of Nature in any given Instance; trace these to some General Principles, or Laws of Operation; and then apply these Principles or Laws to the explaining of other Phaenomena. (The Elements of moral Philosophy, 1754, p. 7-8)

Turnbull and the ‘spirit’ of the experimental method

Juan Gomez writes…

You will probably recognize the following phrase: ‘An attempt to introduce the experimental Method of Reasoning into moral Subjects.’ It is the subtitle of David Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature of 1739-40, and the first explicit mention of the application of the experimental method in moral topics. Many scholars have pointed to it, and claimed that Hume was the first one to go forward with this attempt. However, others (Tom Beauchamp, Alexander Broadie) have also noticed that this idea did not originate with Hume. I will show here that the ‘spirit’ of the experimental method was very much alive at least 20 years before the publication of Hume’s Treatise. In fact, contrary to the most commonly held view, Hume should not be the reference point when studying the emergence of the “science of man”. Rather, we should look at the Aberdeen philosophers, in particular at George Turnbull and his lectures at Marischal College in the 1720’s.

I will make a prima facie case for this claim with only a few quotes (available in this document), but please do contact me if you are interested in the topic, since there is more than enough evidence that I would be happy to discuss with you.

To begin with, Hume was not the first to allude to the application of the experimental method in moral philosophy. Francis Hutcheson had already done this in his 1725 Inquiry. The subtitle of this work explains that it contains the following:

- the Principles of the late Earl of Shaftesbury are explained and defended against the Fable of the Bees; and the Ideas of Moral Good and Evil are established, according to the Sentiments of the Ancient Moralists, with an attempt to introduce a Mathematical Calculation on subjects of Morality. (emphasis added)

Hutcheson doesn’t use the words ‘experimental method’, but saying that he will give a ‘mathematical calculation on subjects of morality’ is perfectly in line with the spirit of the experimental method (specifically with the Newtonian method). To be fair to Hume, he does recognize Hutcheson as one of the philosophers who has “begun to put the science of man on a new footing.” (Treatise (1739), Introduction, p. 6-7) So Hume might have recognized that he was not the first, but a number of modern scholars have not.

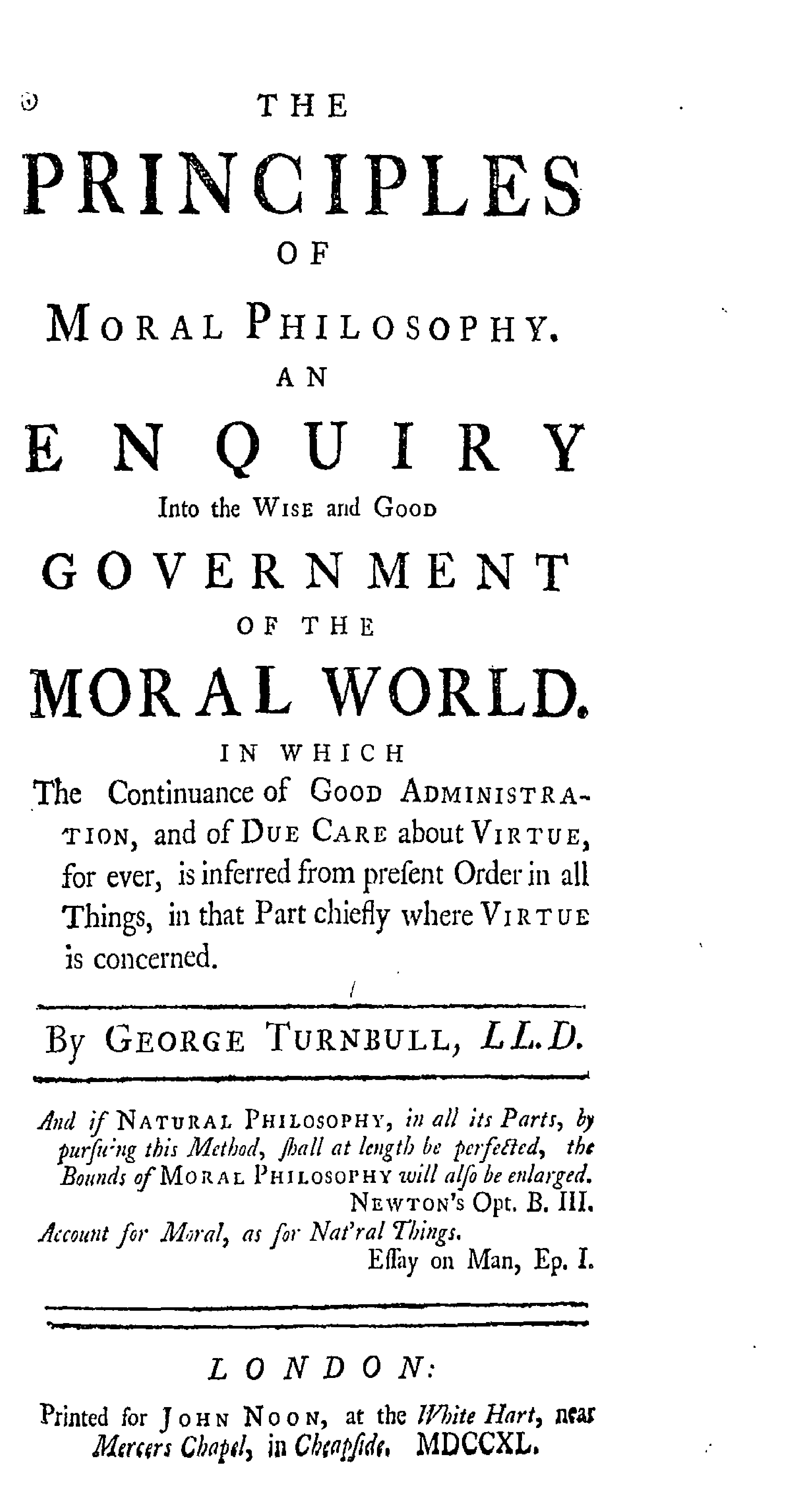

Moving on to George Turnbull, whom I believe is mistakenly underrated as a figure of the Scottish Enlightenment, published his Principles of Moral Philosophy in 1740, the same year Hume published the third volume of his Treatise, which is on Morals. This would at least lead us to think that both Hume and Turnbull were working on the application of the experimental method in morality at the same time. But as Turnbull mentions in the introduction to his Principles, his book is based on the lectures he gave at Marischal College between 1721 and 1726, around the time when Hume was a student at the University of Edinburgh. Besides the numerous remarks in the Principles that show Turnbull’s devotion to the experimental method, there is a key document that shows that he was teaching the young Aberdeen students the moral philosophy he explains in the book he published 17 years later. The document is the 1723 graduation thesis, which the graduating students (Thomas Reid among them) had to defend, titled De scientiae naturalis cum philosophia morali conjunctione (On the unity of natural science and moral philosophy).

I am currently working on the 1723 thesis, and at this moment I can let you know that it is strengthening my belief in the importance of Turnbull in the development of the ‘science of man.’ For now I’ll leave you with enough quotes from the Principles that show that if we want to study the development of the science of morals, we should start focusing more on Turnbull and Aberdeen, and less on Hume and Edinburgh.

Experimental Method in Moral Philosophy

Juan Gomez writes…

This is just a quick summary of the project I’m working on, so you can get a grasp of it, hopefully get interested, and discuss related issues with us. Our Marsden project as a whole revolves around the experimental/speculative distinction in the early modern period (see project description). My interest is to trace and study such distinction within the moral philosophers and the texts produced by them. I’m trying to find answers to the following questions:

- Was the experimental method actually being applied in moral philosophy, or did they use it just as a rhetorical tool?

- Can introspection amount to more than just speculation?

These are just two of the questions that have come up in my research. I should point out here that I’m focusing only on British philosophers in the Eighteenth century, since it seems to be the most fertile ground for my interests. There is enough evidence to show that the British philosophers (Hutcheson, Turnbull, Hume, Reid, Fordyce) were using the language of experimental philosophy in their moral treatises, but this is a different thing from actually following the guidelines of the experimental method of natural philosophy and applying it in moral topics. And even when they were following such guidelines, the most important tool for acquiring knowledge of the “science of man” was introspection, and it is just not clear how different this is from plain speculation.

It seems that most of the eighteenth-century British philosophers (especially Turnbull and Hume) dealing with moral topics tried to fulfill the following ‘prediction’ made by Newton:

- if Natural Philosophy, in all its Parts, by pursuing this [experimental] Method, shall at length be perfected, the Bounds of Moral Philosophy will also be enlarged.” (Newton’s Optics. Book 3, Query 31).

We are trying to find how far they succeeded in making moral philosophy a ‘moral science’ by following the experimental method.

At the moment I’m studying George Turnbull’s Principles of Moral Philosophy (1749), and I’ve come across many interesting findings, which make me realize how important this philosopher and teacher was for the Scottish Enlightenment, and how he has been overlooked and underrated. In future posts I will tell you more about Turnbull’s philosophy, and why I believe he is of extreme importance for understanding philosophy in the Scottish Enlightenment. For the time being I leave you with this quick description of my research, and welcome any comments or questions you have.