Revisiting our 20 theses

Peter Anstey writes …

In March 2011 we posted 20 core theses about the emergence and fate of early modern experimental philosophy. After two years of further research we have found that a number of them needed updating. We take this as a sign of progress and want to thank our readers for their hand in developing our thinking. Here is the revised set.

General

1. The distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy (ESD) provided the most widespread terms of reference for philosophy from the 1660s until Kant.

2. The ESD emerged in England in the late 1650s, and while a practical/speculative distinction in philosophy can be traced back to Aristotle, the ESD cannot be found in the late Renaissance or the early seventeenth century.

3. The main way in which the experimental philosophy was practised from the 1660s until the 1690s was according to the Baconian method of natural history.

4. The Baconian method of natural history fell into serious decline in the 1690s and is all but absent in the eighteenth century. The Baconian method of natural history was superseded by an approach to natural philosophy that emulated Newton’s mathematical experimental philosophy.

Newton

5. The ESD is operative in Newton’s work, from his early work on optics in the 1670s to the final editions of Opticks and Principia published in the 1720s.

6. In his optical work, Newton’s use of queries represents both a Baconian influence and (conversely) a break with Baconian experimental philosophy.

7. While Newton’s anti-hypothetical stance was typical of Fellows of the early Royal Society and consistent with their methodology, his mathematization of optics and claims to certainty were not.

8. In his early work, Newton’s use of the terms ‘hypothesis’ and ‘query’ are Baconian. However, as Newton’s distinctive methodology develops, these terms take on different meanings.

Scotland

9. Unlike natural philosophy, where a Baconian methodology was supplanted by a Newtonian one, moral philosophers borrowed their methods from both traditions. This is revealed in the range of different approaches to moral philosophy in the Scottish Enlightenment, approaches that were all unified under the banner of experimental philosophy.

10. Two distinctive features of the texts on moral philosophy in the Scottish Enlightenment are: first, the appeal to the experimental method; and second, the explicit rejection of conjectures and unfounded hypotheses.

11. Experimental philosophy provided learned societies (like the Aberdeen Philosophical Society and the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh) with an approach to knowledge that placed an emphasis on the practical outcomes of science.

France

12. The ESD is evident in the methodological writings of the French philosophes associated with Diderot’s Encyclopédie project, including the writings of Condillac, d’Alembert, Helvétius and Diderot himself.

Germany

13. German philosophers in the first decades of the eighteenth century knew the main works of British experimental philosophers, including Boyle, Hooke, other members of the Royal Society, Locke, Newton, and the Newtonians.

14. Christian Wolff emphasized the importance of experiments and placed limitations on the use of hypotheses. Yet unlike British experimental philosophers, Wolff held that data collection and theory building are simultaneous and interdependent and he stressed the importance of a priori principles for natural philosophy.

15. Most German philosophers between 1770 and 1790 regarded themselves as experimental philosophers (in their terms, “observational philosophers”). They regarded experimental philosophy as a tradition initiated by Bacon, extended to the study of the mind by Locke, and developed by Hume and Reid.

16. Friends and foes of Kantian and post-Kantian philosophies in the 1780s and early 1790s saw them as examples of speculative philosophy, in competition with the experimental tradition.

From Experimental Philosophy to Empiricism

17. Kant coined the now-standard epistemological definitions of empiricism and rationalism, but he did not regard them as purely epistemological positions. He saw them as comprehensive philosophical options, with a core rooted in epistemology and philosophy of mind and consequences for natural philosophy, metaphysics, and ethics.

18. Karl Leonhard Reinhold was the first philosopher to outline a schema for the interpretation of early modern philosophy based (a) on the opposition between Lockean empiricism (leading to Humean scepticism) and Leibnizian rationalism, and (b) Kant’s Critical synthesis of empiricism and rationalism.

19. Johann Gottlieb Buhle and Wilhelm Gottlieb Tennemann were the first historians to craft a detailed, historically accurate, and methodologically sophisticated history of early modern philosophy based on Reinhold’s schema.

20. Tennemann’s direct and indirect influence is partially responsible for the popularity of the standard narratives of early modern philosophy based on the conflict between empiricism and rationalism.

Any comments on or tweaks to these 20 theses would be most welcome.

Robert Saint Clair

Peter Anstey writes…

It is not uncommon for very minor contributors to early modern thought to go unnoticed, but every now and then they turn out to be worth investigating. One such person is Robert Saint Clair. A Google search will not turn up much on Saint Clair, and yet he was a servant of Robert Boyle and a signatory to and named in Boyle’s will. He promised twice to supply the philosopher John Locke with some of Boyle’s mysterious ‘red earth’ after his master’s death, and a letter from Saint Clair to Robert Hooke was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (vol. 20, 1698, pp. 378–81).

What makes Saint Clair interesting for our purposes is his book entitled The Abyssinian Philosophy Confuted which appeared in 1697. For in that book, which contains his own translation of Bernardino Ramazzini’s treatise on the waters of Modena, Saint Clair attacks Thomas Burnet’s highly speculative theory of the formation of the earth. I quote from the epistle to the reader:

I shall not care for the displeasure of these men of Ephesus [Burnet and others], whose trade it is to make Shrines to this their Diana of Hypothetical Philosophy, I mean who in their Closets make Systems of the World, prescribe Laws of Nature, without ever consulting her by Observation and Experience, who (to use the Noble Lord Verulams words) like the Spider … spin a curious Cob-web out of their Brains … (sig. a4)

The rhetoric of experimental philosophy could hardly be more obvious. Burnet and the other ‘world-makers’ are criticized for being adherents of ‘Hypothetical Philosophy’, for making ‘Systems of the World’, and for not consulting nature by ‘Observation and Experience’. He also praises Ramazzini’s work for being ‘the most admirable piece of Natural History’ (sig. a2). Saint Clair rounds off this passage with a reference to Bacon’s famous aphorism (about which we have commented before) from the New Organon comparing the spider, the ant and the bee to current day natural philosophers (I. 95).

What can we glean from Saint Clair’s critique here? First, it provides yet another piece evidence of the ubiquity of the ESD in late seventeenth-century England: the terms of reference by which Saint Clair evaluated Burnet were clearly those of experimental versus speculative philosophy.

Second, it is worth noting the term ‘Hypothetical Philosophy’. This expression was clearly ‘in the air’ in the late 1690s in England. For instance, it is found in John Sergeant’s Solid Philosophy Asserted which was also published in 1697. Indeed, it is the very term that Newton used in a draft of his letter of 28 March 1713 to Roger Cotes to describe Leibniz and Descartes years later. Clearly the term was in use as a pejorative before Newton’s attack on Leibniz.

Saint Clair has been almost invisible to early modern scholarship on English natural philosophy and yet his case is a nice example of the value of inquiring into the plethora of minor figures surrounding those canonical thinkers who still capture most of our attention. I would be grateful for suggestions as to names of others whom I might explore.

Incidentally, Saint Clair obviously thought that John Locke might be interested in his book, for we know from Locke’s Journal that he sent him a copy.

Hypotheses and political philosophy: Tenison against Hobbes

Peter Anstey writes …

Our research project at Otago on experimental philosophy has largely focused on natural philosophy. However, while early modern experimental philosophy had its origins in natural philosophy in mid-seventeenth-century England, it quickly impacted on other disciplines.

Tenison (1636-1715)

Experimental philosophers, as we have repeatedly stressed in previous posts on this blog, regarded Francis Bacon as their progenitor and promoted observation and experiment and decried speculation and the use of hypotheses and premature system building.

It is of great interest, therefore, to find elements of the method of experimental natural philosophy being applied as early as 1670 in an attack on Thomas Hobbes’ doctrine of the state of nature. The divine Thomas Tenison in his The Creed of Mr Hobbes examined, London, 1670, attacked Hobbes’ doctrine of the state of nature for being the product of Hobbes’ own imagination. Hobbes postulated in his Leviathan (1651) that before the existence of civil society all people were in a state of ‘warre, as is of every man, against every man’’ in which life is ‘solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short’. Here is how Tenison attacks him:

It is a very absurd and unsecure course to lay the ground-work of all civil Polity and formed Religion, upon such a supposed state of Nature, as hath no firmer support than the contrivance of your own fancy. (p. 131)

For Tenison, it is one thing for the various competing cosmological hypotheses of Ptolemy, Tycho, Copernicus and Descartes to be entertained, for, even if none of these happens to be true, ‘the interests of Men remain secure’. But it is another thing entirely to found the doctrines of civil, moral and Christian philosophy on ‘Hypotheses, framed by the imagination’. Tenison continues:

such persons who trouble the World with fancied Schemes and Models of Polity, in Oceana’s and Leviathans, ought to have in their Minds an usual saying of the most excellent Lord Bacon concerning a Philosophy advanced upon the History of Nature. That such a work is the World as God made it, and not as Men have made it: for that it hath nothing of Imagination. (pp. 131–2)

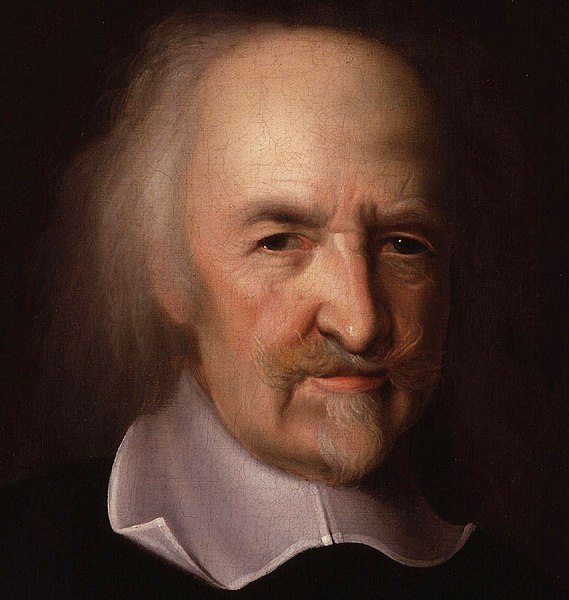

Hobbes (1588-1679)

Note the appeal to Bacon, the reference to natural history and the criticism of philosophy based upon fancies. (Note too the reference to James Harrington’s The Commonwealth of Oceana, 1656.) And yet Tenison does not appeal to observation and experiment because Hobbes’ doctrine as he conceives it is about a past state in human history. Instead he believes that civil philosophy should use ‘reason assisted with Memory touching the passed state of the World’ (p. 131).

What I would like to know is whether this the first use of aspects of the method of experimental philosophy to critique political philosophy?

Cartesian Empiricisms – a Reply

Peter Anstey writes …

The forthcoming book Cartesian Empiricisms edited by Mihnea Dobre and Tammy Nyden promises to extend our knowledge of the experimental practices and philosophy of experiment amongst many of Descartes’ followers.

Dobre, however, claims that the book will offer more than a study of these writers. He says in his recent post that what we find in these neo-Cartesians ‘seems to escape the ESD’ (experimental–speculative distinction, my italics). In what sense might it be true that Cartesians doing experiments might escape the ESD? Is it that the ESD cannot explain them? Or, more strongly, is it that their experimental practices contradict the central tenets of the actors’ categories of experimental philosophy and speculative philosophy? And what is the value of persisting with the term ‘empiricism’ to describe the neo-Cartesians’ engagement with experiment?

In my view, the fact that some Cartesians performed experiments is of great interest, but it is also grist for our mill: it actually enriches the evidential base for the claims that we have made on this blog and in recent publications. For it shows that, like all other speculative systems, Cartesian natural philosophy was also subject to the court of experiment.

We have never claimed that proponents of speculative systems like Cartesianism were necessarily opposed to experimental verification of their theories. Nor have we ever claimed that all experimental philosophers were adamantly opposed to speculation: some were, but others, like Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke, were not.

We have claimed that the Cartesian vortex theory came to be regarded by many as the archetypal speculative theory in natural philosophy. Indeed, this was the virtually the standard view in England from the late 1690s when the term ‘our vortex’ starts to disappear and Newton’s arguments against the Cartesian system began to be widely appreciated. But none of this implies that our claims about the ESD need somehow to be modified. In fact, there is evidence that distaste for speculative system building and a belief in the need for the construction of Baconian natural histories were constituents of the general methodological background to mid-seventeenth-century Parisian natural philosophy. The first article of the constitution of the Montmor academy, which met in Paris from the mid-1650s to around the time of the formation of the Académie des Sciences, says:

The purpose of the company shall not be the vain exercise of the mind on useless subtleties (subtiltés inutiles), but the company shall set before itself always the clearer knowledge of the works of God, and the improvement of the conveniences of life, in the Arts and Sciences which seek to establish them.

The anti-speculative element here is hard to miss. (Interestingly, none of the articles mention experiment.) Furthermore, it is well known that Christiaan Huygens recommended to Colbert that the newly formed Adadémie construct natural histories after the manner of Verulam.

What I am hoping to glean from Cartesian Empiricisms is an answer to the following question:

Did the Cartesians practise a form of experimental philosophy analogous to that of the Fellows of the early Royal Society?

This question is important for a number of reasons. The work of Trevor McClaughlin on Rohault, for example, has shown that early Cartesians carried out experiments. Yet we still lack a detailed assessment of the nature, theory and practice of experiments amongst the neo-Cartesians in the three decades after Descartes’ death. There is no doubt that they performed experiments for illustrative purposes and repeated many classic experiments for pedagogical purposes. But did they engage in experimental programs with a view to acquiring new knowledge of nature and to modifying and developing natural philosophical knowledge?

What makes this issue particularly pressing is that there is evidence from the late 1650s and early 1660s that the natural philosophers who met in the Parisian academies, such as the Montmor academy which included several prominent Cartesians, performed experiments, but were not really practising experimental natural philosophy. Henry Oldenburg reported to Michaelis in April 1659 that the philosophical academies in Paris: ‘are rich in promises, few in performance’ (Corresp. of Oldenburg, 1: 241). Three months later Oldenburg wrote to Boyle from Paris saying:

we have severall meetings here of philosophers and statists which I carry your nevew to, for to study men as well as books; though the French naturalists are more discursive, than active or experimentall. (Corresp. of Oldenburg, 1: 287)

My hope, therefore, is that Cartesian Empiricisms will answer this very pressing question.

Cartesian empiricisms

Mihnea Dobre from the universities of Bucharest and Nijmegen writes…

As readers of this blog know, the classic division between continental Rationalists and British Empiricists fails to provide an accurate picture of the early modern period. The Otago team has already offered extensive evidence of the complexity of seventeenth-century natural philosophy. Replacing the traditional-historiographical distinction between Rationalism and Empiricism (RED) with actor-category division of experimental versus speculative philosophy (ESD) is one step ahead in getting a more meaningful image of the philosophical debates that marked the formation of modern philosophy and science.

However, in this post, I would like to focus on a different aspect, which seems to escape the ESD distinction and further complicates our image of the late-seventeenth century. At the same time, I take this opportunity to announce a forthcoming volume, Cartesian Empiricisms, which Tammy Nyden and I are co-editing in the Springer series on the Studies in History and Philosophy of Science.

While this juxtaposition between “Cartesianism” (which for a long time has been associated with rationalism, armchair philosophizing, speculative thinking, or a purely theoretically driven philosophical approach) and “Empiricism” (which besides its traditional opposition to “Rationalism” is still preferred by many to describe an approach based on experiment and experimentation) might look odd at first, it sheds, in fact, a completely new light upon the development of natural philosophy in the second half of the seventeenth century.

Descartes’s philosophy has been discussed, interpreted and revaluated constantly in our histories of both philosophy and science. Yet, a more in-depth study of what happens after Descartes’s death is missing. We hope Cartesian Empiricisms will fill this gap, contributing to the exploration of some now-forgotten philosophical figures, which were not only prime representatives of the philosophical debates of their time but were opening the possibility of a more experimentally oriented natural philosophy.

After Descartes’s death in 1650, his philosophy was challenged in various ways and one of the most common forms of attack was to disprove it with empirical evidence. Take, for example, this curious case from the Philosophical Transactions, one of the first scientific journals. On June 3, 1667, an observational report described the puzzling case of a turtle that was still able to move even with her head missing:

there came a Letter from Florence, Written by M. Steno, which has also somewhat perplext the followers of Des Cartes. A Tortoise had its head cut off, and yet was found to move its foot three days after. Here was no Communication with the Conarium [i.e. the pineal gland]. As this seems to have given a sore blow to the Cartesian Doctrine, so the Disciples thereof are here endeavouring to heal the Wound (p. 480).

Such instances that do not cohere with Descartes’s natural philosophy can be found in various places in the new scientific journals, as well as in public debates and philosophical treatises. A well-known case is that of the collision rules that went through a number of critical evaluations during the 1660s. Physics, anatomy, and psychology are among the most heated areas of contestation for Descartes’s natural philosophy. Cartesians reacted to the new challenges by both trying to complement or correct Descartes’s philosophical corpus with needed additions, but also by incorporating into their practices new methods. Cartesian Empiricisms will highlight such attempts:

Ch. 1. Introduction

Section I: Cartesian Philosophy: Receptions and Context

Ch. 2. “Censorship, Condemnations, and the Spread of Cartesianism” by Roger Ariew

Ch. 3. “Was there a Cartesian Experimentalism in the 1660’s France?” by Sophie Roux

Ch. 4. “Dutch Cartesian Empiricism and the Advent of Newtonianism” by Wiep van Bunge

Ch. 5. “Heat, Action, Perception: Models of Living Beings in German Medical Cartesianism” by Justin Smith

Section II: Cartesian Disciplines

Ch. 6. “The Cartesian Psychology of Antoine Le Grand” by Gary Hatfield

Ch. 7. “Experimental Cartesianism and the Occult (1675-1720)” by Koen Vermeir

Ch. 8. “Rohault’s Cartesian Physics” by Mihnea Dobre

Ch. 9. “De Volder’s Cartesian Physics and Experimental Pedagogy” by Tammy Nyden

Ch. 10. “Empiricism without Metaphysics: Regius’ Cartesian Natural Philosophy” by Delphine Bellis

Ch. 11. “Robert Desgabets on the Physics and Metaphysics of Blood Transfusion” by Patricia Easton

Ch. 12. “Rohault, Regis and Cartesian Medicine” by Dennis Des Chene

Ch. 13. “Could a Practicing Chemical Philosopher be a Cartesian?” by Bernard Joly

It is particularly interesting how many of the individual Cartesians discussed in this volume blend theoretical and experimental elements. Experience and experimentation become – for some of them – constitutive parts of their Cartesian natural philosophies, thus making it harder to classify them with our current historiographical categories. We hope that our volume will open new discussions about such categories and will encourage the exploration of other branches of Cartesian philosophy.

Early Modern HPS Session Details

History and Philosophy of Science in Australia: Looking Forward

National Committee for History and Philosophy of Science workshop, University of Sydney, New Law School Annexe 342

27 September 2012: University of Sydney

8.50 Peter Anstey (Otago/Sydney) Introductory comment

8.50 Luciano Boschiero (Campion): History of science in the liberal arts: its tradition and future

9.08 Peter Harrison (Queensland): Early Modern HPS at UQ: Current Projects and Future Prospects

9.26 Gerhard Wiesenfeldt (Melbourne): Back to the basics? Changing perspectives in the digital age

9.45 Ofer Gal (Sydney): Passionate knowledge

10.04 John Schuster (Sydney/Campion): Descartes Studies / Scientific Revolution Studies: The Historiographical Imperatives

10.23 Alan Chalmers (Sydney): Mechanical philosophy, experimental philosophy and Descartes

10.41 Peter Anstey: Concluding remarks

Reflections on HPS

Peter Anstey writes…

It is time to restart the conversation about early modern HPS as we lead up to the Sydney conference which commences in two week’s time.

I am currently in Cambridge and have had a number of talks with philosophers and people working in HPS here and in Paris. A common theme has been that they don’t believe that there is anything particularly unique about HPS in terms of methodology and the sorts of outputs of its practitioners. They are happy to work in HPS departments and hope that the discipline continues, but they are noticing changes in the disciplinary mix with a clear shift towards the social sciences and to sciences studies.

I should like to propose a tentative historical explanation of the current situation of HPS as a disciplinary division with the university sector. I raise it for discussion rather than as my own position statement.

It is very hard to do new, innovative research on a historical period, particularly one as rich as the early modern period, without doing interdisciplinary research. In the 1950s and 1960s and there was little institutional recognition of interdiciplinary research in Anglophone universities. At the same time the philosophy of science was undergoing very exciting developments. There was the hotbed at the LSE in London and Kuhn was nearing his peak in Princeton, to choose just two obvious examples. Now what is striking about these developments in the philosophy of science is that they were inextricably bound to historical episodes in the history of science – Kuhn’s paradigm shifts needed actual examples from the history of science. The combination of these two factors, and perhaps others, led to a new form of interdisciplinary research output – a hybrid if you will – that could not be written without the intersecting of history of science and philosophy. Soon institutional niches opened up to accommodate groups of researchers who were working in this overtly interdisciplinary way. (We could add another paragraph on how sociology of science and the study of technology were soon grafted on, but you get the general picture.)

That was then. It appears that today, by contrast, there is a widespread recognition of the value and the almost ineliminable need for interdisciplinary research in the traditional disciplines themselves: history, philosophy, literature, languages, music, theology. Interdisciplinarity is everywhere and is not merely tolerated but celebrated and funded. At the same time the philosophy of and the history of science have become far more specialized and diffuse. There is no unified set of problems or approaches or dominant players that provide the fulcrum around which HPS is practised. Koyré, Kuhn, Popper, Lakatos, etc. are now part of the history itself.

The result of this higher tolerance of and wider practice of interdisciplinary research, combined with the veritable explosion of and diversification of the history of science and the philosophy of science, is that there is now far less pressure for scholars to find a separate, interdisciplinary, institutional niche within which to work and there is far less of a sense that the methodology of those who do HPS is really all that different from someone studying, say, early modern theology or literature.

A positive consequence of this for HPSers is that we can now celebrate the fact that scholars in other disciplines are working in the way we always have. A negative consequence is that it’s now harder to point out what is unique to HPS either in terms of its methodology or its research outputs. It is, therefore, harder to justify the existence of institutional niches set up for HPS on methodological grounds or in terms of research outputs. The upshot of all of this is that HPS is both in a stronger position and a weaker position. It is now better understood and appreciated because its methods are widely practised by others. Yet it is less unique, less distinctive within the disciplinary matrix in which it is situated.

Denis Diderot: the last true Baconian?

Peter Anstey writes…

There were many types of Baconianism in the eighteenth century and many philosophers and natural philosophers traced their lineage from Bacon or regarded Bacon as the progenitor of views that they espoused. And yet most of these self-proclaimed ‘Baconians’ held views that Bacon himself would hardly recognize or they adhered to what, at best, could be described as a truncated form of Baconianism. A nice example is George Adams Jr whose views on the method of reasoning in natural philosophy in his Lectures on Natural and Experimental Philosophy (1794) (discussed previously on this blog) amount to little more than a summary of the first book of Bacon’s Novum organum (1620).

What would it take then for someone to be a true Baconian? Of course, the question itself is problematic because there is no principled way of determining the necessary and sufficient conditions that would settle the issue. But let us run with the question nonetheless.

Given the prominence of Bacon’s method of natural history in his conception of how we are to acquire knowledge of nature – that is, given the quality and quantity of writings that he devoted to natural history and the efforts he expended in assembling his own exemplar histories in the last years of his life – I suggest that to be a true Baconian one must (at least) be an advocate of the Baconian method of natural history. If this is right, then as far as I am aware, the last true Baconian was the French philosophe Denis Diderot (1713–1784).

Denis Diderot (1713 - 1784)

Diderot’s ‘Prospectus’ for the Encyclopédie, was first published in 1750 and then appended in a modified form to the ‘Preliminary Discourse’ of the first volume of the Encyclopédie itself in 1751. It presents an overtly Baconian scheme of the sciences set within a tripartite faculty psychology à la Bacon, but more importantly, it shows a clear understanding and acceptance of the structure and content of Bacon’s account of the overall project of natural history. Drawing heavily on Bacon’s De augmentis scientiarum he tells us that:

The history of uniform nature is divided, following its principal objects, into: celestial history or history of the stars, of their movements, sensible appearances, etc., without explaining their cause by systems, hypotheses, etc. (It is a matter here only of pure phenomena.) Into meteorological history such as winds, rains, tempests, thunder, aurora borealis, etc. Into the history of the earth and the sea, or of mountains, rivers, streams, currents, tides, sands, soils, forests, islands, configurations of the earth, continents, etc. Into history of minerals, into history of vegetables, into history of animals. Whence results a history of the elements, of the apparent nature, sensible effects, movements, etc., of fire, air, earth, and water. (Preliminary Discourse, Chicago, 1995, 147)

(Regular readers of this blog will note the decrying of systems and hypotheses as hallmarks of a commitment to the experimental philosophy.)

Yet Diderot does not merely reproduce the structure and content of Bacon’s method of natural history, he also appreciated the heuristic structure of these histories and the fact that they needed to be subject to what Bacon called interpretatio naturae, the interpretation of nature. For, in 1754 Diderot published a work entitled On the Interpretation of Nature which, as many scholars have recognized, is very Baconian in character. It is, in effect, Diderot’s own version of Book Two of Bacon’s Novum organum. To be sure it lacks any extended discussion of Baconian induction and prerogative instances, but it is written in aphoristic form and contains many Baconian themes including advice on experimenting, the use of queries and conjectures and concrete natural philosophical examples. Surely on this evidence Diderot must qualify as a true Baconian. Was he the last?

The origins of ‘solar system’

Peter Anstey writes…

The Cartesian vortex theory of planetary motions came under serious suspicion in England in the early 1680s. To be sure, many still spoke of ‘our vortex’ well into the 1680s and ’90s, such as Robert Boyle in his Notion of Nature of 1686 (Works, eds. Hunter and Davis, London, 1999–2000, 10, p. 508), but by the early 1690s the new Newtonian cosmology was coming to be widely accepted and many in England thought that the vortex theory had been disproved. By that time the vortex theory of planetary motions had come to be seen as the archetypal form of speculative natural philosophy. What was required then was a new descriptor for that cosmological structure in which the earth is located. And a new term was soon deployed, namely, ‘solar system’.

Some have claimed that it was John Locke who coined the term ‘solar system’. In fact, the OED lists Locke’s Elements of Natural Philosophy, which it dates at c.1704, as the earliest occurrence. However, the term first appears in his writings in Some Thoughts concerning Education of 1693 where speaking of Newton’s ‘admirable Book’ about ‘this our Planetary World’, he says,

his Book will deserve to be read, and give no small light and pleasure to those, who willing to understand the Motions, Properties, and Operations of the great Masses of Matter, in this our Solar System, will but carefully mind his Conclusions… (Clarendon edition, 1989, p. 249)

Interestingly, a quick word search of EEBO reveals that the term was also used by Richard Bentley in his seventh Boyle lecture of 7 November 1692, but published in 1693 in a volume that Locke owned (Folly & Unreasonableness of Atheism, London). Bentley uses the term in an argument for the existence of God on the basis of the claim that the fixed stars all have the power of gravity. It is God who prevents the whole system from collapsing into a common centre:

here’s an innumerable multitude of Fixt Starrs or Suns; all of which are demonstrated (and supposed also by our Adversaries) to have Mutual Attraction: or if they have not; even Not to have it is an equal Proof of a Divine Being, that hath so arbitrarily indued Matter with a Power of Gravity not essential to it, and hath confined its action to the Matter of its own Solar System: I say, all the Fixt Starrs have a principle of mutual Gravitation; and yet they are neither revolved about a common Center, nor have any Transverse Impulse nor any thing else to restrain them from approaching toward each other, as their Gravitating Powers incite them. Now what Natural Cause can overcome Nature it self? What is it that holds and keeps them in fixed Stations and Intervals against an incessant and inherent Tendency to desert them? (p. 37, underlining added)

There is no evidence, however, that Bentley was using the term as an alternative to ‘our vortex’. In a letter to Newton of 18 February 1693 he speaks unabashedly of matter that ‘is found in our Suns Vortex’.

Who published the word first? Bentley’s seventh Boyle lecture was not published separately, but appeared in the 1693 volume, the last lecture of which was not given its imprimatur until 30 May that year. Locke’s book was advertised in the London Gazette #2886 for 6–10 July. I have not been able to establish exactly when Bentley’s volume appeared, but it’s not mentioned in the London Gazette before #2886.

Whatever the case, it is most likely that the term was already ‘in the air’ and history shows that it was soon widely used and, of course, it is a commonplace today.

(N.B. This post also appears on the Early Modern at Otago blog.)

Francis Bampfield: an early critic of experimental philosophy

Peter Anstey writes…

In a recent article Peter Harrison has drawn our attention to the phenomenon of experimental Christianity in seventeenth-century England (‘Experimental religion and experimental science in early modern England’, Intellectual History Review, 21 (2011)). In this post I would like to take up where Harrison left off and discuss one proponent of experimental religion whom Harrison does not mention, namely Francis Bampfield (1614–1684). Bampfield provides an interesting case study because while he was a promoter of experimental Christianity, he was also a harsh critic of the new experimental natural philosophy.

In two works from 1677, All in One and SABBATIKH, Bampfield lays out his case against experimental natural philosophy. In his view the source of all useful and certain knowledge is the Scriptures.

Practical Christianity, and experimental Religion is the highest Science, and the noblest Art, and the most honourable Profession, which gives light to all inferiour knowledges, and would admit into the Royalest Society, and draw nearest in resemblance and conformity, to the glorified Fellowship in the Heavenly College above, where their knowledge is perfected in visional intuitive light. Here is the prime Truth, the original Verity, as to the manifestativeness of it in legible visible ingravings, which would carry progressively into other Learning contained therein: all here is reducible to practice and use, to life and conversation; here existences and realilties are contemplated and proved, not mere Ideas and conceits speculated as elsewhere. (All in One, p. 12)

It is the mere ideas and conceits of the new experimental philosophy of the Royal Society, or the Fellows of Gresham College, that Bampfield is concerned to expose:

How many thousands have by their wandring after such misguiders left and lost their way in the dark, where their Souls have been filled with troublesome doubts, and with tormenting fears, exposing them to violent temptations of Atheism and Unbelief? and what wonder, that it is thus with the Scholar, when some of the learnedest of the Masters themselves have resolved upon this, as the conclusion of all their knowledge, that, All things are matter of doubtful questionings, and are intricated with knotty difficulties, and do pass into amazing uncertainties, and resolve into cosmical suspicions? And this, not only is the deliberate Judgement of particular Virtuoso’s in our day, but has been the publick determination of an whole University. (All in one, p. 3)

What are these ‘knotty difficulties’ that pass into ‘amazing uncertainties’ resolving into ‘cosmical suspicions’? The alert reader will no doubt see here a direct allusion to Robert Boyle’s Tracts of 1670 in which he discusses cosmical qualities that seem to have ‘such a degree of probability, as is want to be thought sufficient to Physicall Discourses’ (Works of Robert Boyle, eds Hunter and Davis, London, 1999–2000, 6, p. 303). Boyle appended to his essay on cosmical qualities another on cosmical suspicions which contains just the sort of speculative reflections that Bampfield is alluding to here. (As far as I can determine, Boyle’s is the first work in English that uses the term ‘cosmical suspicions’.) That Bampfield was a close reader of Boyle’s writings comes out in a later passage which I quote in extenso:

There is an honourable Virtuosus, who has travelled far in Natures way, and has made some of the deepest inquiries into Experimental, Corpuscular, or Mechanical Philosophy, that in the requisites of a good Hypothesis amongst others of them, doth make this to be one of its conditions, that it fairly comport not only with all other truths, but with all other Phaenomena of Nature, as well as those ’tis fram’d to explicate, and that, not only none of the Phaenomena of Nature, which are already taken notice of do contradict it at the present, but that, no Phaenomena that may be hereafter discovered, shall do it for the future. Let it therefore from hence be considered, whether seeing, that History of Nature, which is but of human indagation and compiling, is so incomplete and uncertain, and many things may be discovered in after-times by industry, or in some other way by providential dispensing, which are not now so much as dreamed of, and which may yet overthrow Doctrines speciously enough accommodated to the Observations, that have been hitherto made (as is by himself fore-seen and acknowledged) whether now, the only prevention and remedy in this case (which is otherwise so full of just fears, of real doubts, of endless dissatisfaction, and of perplexing difficulties) be not, to bring all sorts of necessary knowledges to the Pan-sophie, the Alness of Wisdom, in the Scriptures of Truth, where none of the forementioned Scriptures have any ground to set their foot on, in regard that Word-Revelations about Natures Secrets, are the unerring products of infinite Wisdom, and of universal fore seeingness, which are always uniform and the same, in their well-established order, and stated ordinary course without any variation, by an unchangeable Law of the All-knowing Truthful Creator, and Governour, and Redeemer. (All in One, pp. 56-7)

Bampfield is, of course, referring to Boyle’s Excellency of Theology (Works, 8, p. 89) and while he is cautious not to be overtly critical of Boyle here, the thrust of his comments is to undermine the epistemic status of the experimental philosophy, calling it ‘incomplete and uncertain’. For, as he says in his sequel SABBATIKH:

the unscriptural way they take in their researches into natural Histories and experimental Philosophy, will never so attain its useful end for the true advance of profitable Learning, till more studied in the Book of Scriptures, and suiting all experiments unto this word-knowledge. (SABBATIKH, p. 53)

It is ‘word knowledge’ and not knowledge of the world that Bampfield is defending. What Boyle himself made of all of this, if it even came to his attention, we will never know. He never mentions Bampfield in any of his works or correspondence.