Paintings as Experiments in Natural and Moral Philosophy

Juan Gomez writes…

About a month ago I published a post on George Turnbull’s Treatise on ancient Painting. There I briefly commented that Turnbull thought that paintings could work as proper samples or experiments for natural and moral philosophy (understood as the ‘science of man’). I want to expand on this issue in this post.

The whole of Turnbull’s Treatise, as he comments at the beginning of chapter seven, is designed to show the usefulness of the imitative arts for philosophy and education in general. After a recollection of the thoughts of the ancient philosophers on these arts, Turnbull dedicates the last two chapters of the book to sketch the reasons for incorporating the arts in the Liberal education program. This is where paintings can serve as samples or experiments.

To understand the role of paintings, it is necessary to point out a general characteristic of Turnbull’s philosophy. He believed that human beings were made to contemplate and to imitate nature, and their happiness was mainly achieved through these two activities. If we take a look and examine all our faculties and powers, we will see that we are perfectly constituted for the study of nature. We acquire knowledge through the observation of nature, and the desire to imitate it leads us to perform experiments that will enhance our understanding of it.

Nature is also the source for the work of the artist:

- The Artist derives all his Ideas from Nature, and does not make Laws and Connexions agreeably to which he works in order to produce certain Effects, but conforms himself to such as he finds to be necessarily and unchangeably established in Nature. (Treatise on Ancient Painting, p. 137)

From this it follows that the paintings of an artist should represent (imitate) nature as it is in reality, following all its laws. With this in mind Turnbull goes on to tell us that paintings in fact serve as samples or experiments for natural and moral philosophy:

- Philosophy is rightly divided into natural and moral; and in like manner, Pictures are of two Sorts, natural and moral: The former belong to natural, and the other to moral Philosophy. For if we reflect upon the End and Use of Samples or Experiments in Philosophy, it will immediately appear that Pictures are such, or that they must have the same Effect. What are Landscapes and Views of Nature, but Samples of Nature’s visible Beauties, and for that Reason Samples and Experiments in natural Philosophy? And moral Pictures, or such as represent parts of human Life, Men Manners, Affections, and Characters; are they not Samples of moral Nature, or of the Laws and Connexions of the moral World, and therefore Samples or Experiments in moral Philosophy? (Treatise, p. 145)

Since the paintings are supposed to represent nature, it is impossible to appreciate them without comparing them to the original (reality). In this sense paintings will provide us with a proper sample of nature that will enhance our knowledge of it. Turnbull’s theory relies on the artist making exact ‘copies’ of nature, and only then can they serve as proper samples. In the case of natural pictures, he allows two sorts of ‘copies’: either exact representations of nature (like a photograph), or imaginary scenes, as long as they conform to the Laws of Nature. If they are not in these categories, then they shouldn’t be taken as proper samples for the study of nature, and in Turnbull’s case, not even as good works of art. Those works of art that do not imitate nature do not give us the pleasure derived from those that do.

Turnbull prescribes a parallel form of realism for moral paintings. These pictures should depict human nature as it really is, and through them we can gain knowledge of our actions and characters:

- Moral Pictures, as well as moral Poems, are indeed Mirrours in which we may view our inward Features and Complexions, our Tempers and Dispositions, and the various Workings of our Affections. ‘Tis true, the Painter only represents outward Features, Gestures, Airs, and Attitudes; but do not these, by an universal Language, mark the different Affections and Dispositions of the Mind? (Treatise, p. 147)

As long as the sole purpose of the arts is to imitate nature, and all the works follow the laws of nature (even in cases of imaginary scenes), Turnbull can count them as having the same effect ‘real’ samples and experiments have.

Locke’s Master-Builders were Experimental Philosophers

Peter Anstey says…

In one of the great statements of philosophical humility the English philosopher John Locke characterised his aims for the Essay concerning Human Understanding (1690) in the following terms:

- The Commonwealth of Learning, is not at this time without Master-Builders, whose mighty Designs, in advancing the Sciences, will leave lasting Monuments to the Admiration of Posterity; But every one must not hope to be a Boyle, or a Sydenham; and in an age that produces such Masters, as the Great – Huygenius, and the incomparable Mr. Newton, with some other of that Strain; ’tis Ambition enough to be employed as an Under-Labourer in clearing Ground a little, and removing some of the Rubbish, that lies in the way to Knowledge (Essay, ‘Epistle to the Reader’).

Locke regarded his project as the work of an under-labourer, sweeping away rubbish so that the ‘big guns’ could continue their work. But what is it that unites Boyle, Sydenham, Huygens and Newton as Master-Builders? It can’t be the fact that they are all British, because Huygens was Dutch. It can’t be the fact that they were all friends of Locke, for when Locke penned these words he almost certainly had not even met Isaac Newton. Nor can it be the fact that they were all eminent natural philosophers, after all, Thomas Sydenham was a physician.

In my book John Locke and Natural Philosophy, I contend that what they had in common was that they all were proponents or practitioners of the new experimental philosophy and that it was this that led Locke to group them together. In the case of Boyle, the situation is straightforward: he was the experimental philosopher par excellence. In the case of Newton, Locke had recently reviewed his Principia and mentions this ‘incomparable book’, endorsing its method in later editions of the Essay itself. Interestingly, in his review Locke focuses on Newton’s arguments against Descartes’ vortex theory of planetary motions, which had come to be regarded as an archetypal form of speculative philosophy.

In the case of Huygens, little is known of his relations with Locke, but he was a promoter of the method of natural history and he remained the leading experimental natural philosopher in the Parisian Académie. In the case of Sydenham, it was his methodology that Locke admired and, especially those features of his method that were characteristic of the experimental philosophy. Here is what Locke says of Sydenham’s method to Thomas Molyneux:

- I hope the age has many who will follow [Sydenham’s] example, and by the way of accurate practical observation, as he has so happily begun, enlarge the history of diseases, and improve the art of physick, and not by speculative hypotheses fill the world with useless, tho’ pleasing visions (1 Nov. 1692, Correspondence, 4, p. 563).

Note the references to ‘accurate practical observation’, the decrying of ‘speculative hypotheses’ and the endorsement of the natural ‘history of diseases’ – all leading doctrines of the experimental philosophy in the late seventeenth century. So, even though Sydenham was a physician, he could still practise medicine according to the new method of the experimental philosophy. In fact, many in Locke’s day regarded natural philosophy and medicine as forming a seamless whole in so far as they shared a common method. It should be hardly surprising to find that Locke held this view, for he too was a physician.

If it is this common methodology that unites Locke’s four heroes then we are entitled to say ‘Locke’s Master-Builders were experimental philosophers’. I challenge readers to come up with a better explanation of Locke’s choice of these four Master-Builders.

Galileo and Experimental Philosophy

Greg Dawes writes…

In a recent conference paper I have argued that in some key respects Galileo’s natural philosophy anticipates the experimental philosophy of the later seventeenth century. I am not claiming that Galileo uses the term “experimental philosophy.” Nor do I claim that he makes any distinction comparable to that between experimental and speculative natural philosophy. His Italian followers in the Accademia del Cimento would later do so, but he does not. Nonetheless, the way in which Galileo undertakes natural philosophy displays at least two of the features that Peter Anstey and his collaborators have argued are characteristic of experimental philosophy.

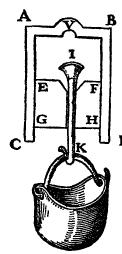

Galileo's sketch of a device to demonstrate the power of a vacuum.

The first of these has to do with the role of experiment. Much of the twentieth-century debate centred on whether Galileo actually performed the experiments about which he writes. But the more important question has to do with the role of experiments in Galileo’s thought. Like his Aristotelian predecessors, Galileo seeks to construct a demonstrative natural philosophy: one in which the conclusions follow with certainty from the premises. But unlike the Aristotelian, he relies on geometrical proofs. Like any mathematical proofs, these can be elaborated in an a priori fashion, without any reference to experience. But whether a particular proof applies to the world of experience – or, better still, whether it accurately describes the structure of the world – can only be ascertained experimentally. It is experiment which tells us which geometrical proof is to be used, even if the geometrical proof itself can be developed independently of experience. (I am relying here on the work of Martha Féher, Peter Machamer, and others.)

Perhaps more importantly, Stephen Gaukroger has argued that experimentation shaped the very way in which Galileo’s physical theories are framed and formulated. Alexander Koyré and others have argued that the laws of Galilean physics are “abstract” laws which refer to an ideal reality. It is true, of course, that in setting aside “impediments” (impedimenti), such as the resistance of the air, Galileo’s proofs do not refer to the world of everyday experience. But it is unhelpful to think of them as an idealisations of, or abstractions from, experienced reality. There is an experienced reality to which they conform. It may not be that of everyday experience, but it is that of carefully controlled physical experiments. It follows that in Galileo’s work, the task of natural philosophy is being rethought. It is no longer the study of reality as revealed to everyday observation; it is the study of that reality revealed in experimental situations.

The second way in which Galileo’s natural philosophy anticipates the later experimental philosophy is in its comparative lack of interest in the mechanisms thought to underlie phenomena. It is not that Galileo was a positivist in our modern sense. There are passages in which he engages in speculation regarding matter theory and on these occasions he favours a corpuscularian view. But such speculations are, as Salviati says in the Two New Sciences, a mere “digression.” Galileo does not consider that his new science requires them. Indeed his work on motion is almost entirely a kinematics – as he freely admits, it says nothing about the causes of motion – but Galileo does not consider it any less significant as a result.

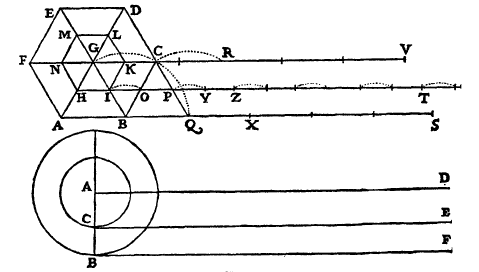

Galileo's solution of the "rota Aristotelis" paradox, demonstrating that a body could be composed of an infinite number of unquantifiable atoms.

This should not be interpreted as a general lack of interest in causation, as Stillman Drake suggests. Galileo shares the ancient desire cognoscere rerum causas (to know the causes of things). But the causal properties Galileo seeks are different from those sought by his predecessors. His causes are the mathematically describable properties of the objects whose behaviour is being explained, properties that no Aristotelian would regard as essential. (Even his atoms are more akin to mathematical points than physical objects.) It is, once again, experimentation that allows us to pick up which of those mathematically describable properties are generally operative and therefore the proper subject of a science. It is this move that allows Galileo, as it would later allow Newton, to be content with a causal account that remains on the level of phenomena, rather than speculating about a realm inaccessible to observation.

In an early dialogue, Galileo has two rustics (contadini) speculating about the new star of 1605. One of them advises his companion to listen to the mathematicians rather than the philosophers, for they can measure the sky the way he himself can measure a field. It doesn’t matter of what material the heavens are made. “If the sky were made of polenta,” he says, “couldn’t they still see it alright?” This is surely something new in the history of natural philosophy.

Postscript:

While I would still defend the individual claims contained here, my continued study of Galileo has made me increasingly cautious about the usefulness of a distinction between experimental and speculative natural philosophy. It is certainly the case that many late seventeenth-century thinkers made such a distinction, but is it a useful one for us to make? I’m not confident that it is.

Experiment certainly played an important role in Galileo’s work, although precisely what that role was continues to be contested. And it is true that Galileo has little interest in speculating about the underlying structure of the world: even if, as he writes, the sky were made of polenta, the mathematicians could still measure it. The problem is that the classical, mathematical tradition out of which he comes — that of astronomy, statics, optics, and (after Galileo) the study of local motion — cannot be helpfully characterized as either experimental or speculative. It certainly uses experiment, but it also reasons a priori, in ways that seem independent of experience.

So perhaps it would be better to have a threefold classification of early modern scientific traditions. (A classification of this kind is suggested by Casper Hakfoort in the last chapter of his Optics in the Age of Euler.) A first tradition would be that of matter theory, which is inevitably speculative insofar as it deals with matters not accessible to direct observation. (This is the realm of Newton’s “hypotheses.”) Corpuscularian proposals would fall into this category, as would Descartes’s vortex theory. A second tradition would be that of experimental natural philosophy, which regarded the results of experiment as themselves significant forms of knowledge, whether or not they could be connected with an underlying theory of the nature of matter. Finally, there is the mathematical tradition that Galileo transformed, so successfully, by producing a mathematical account of local motion.

Individual natural philosophers could engage in all three kinds of activities, but will differ according to the emphasis they place on one or other of them. So although Galileo certainly engaged in experiments, his emphasis was on the kind of reasoning characteristic of the mathematical tradition. It is this form of reasoning, I have come to believe, that cannot be easily fitted into the experimental-speculative scheme.

Newton’s Early Queries are not Hypotheses

Kirsten Walsh writes…

In an earlier post I demonstrated that, in his early optical papers, Newton is working with a clear distinction between theory and hypothesis. Newton takes a strong anti-hypothetical stance, giving theories higher epistemic status than hypotheses. Newton’s corpuscular hypothesis appears to challenge his commitment to this anti-hypothetical position. Today I will discuss a second challenge to this anti-hypotheticalism: Newton’s use of queries.

Newton’s queries have often been interpreted as hypotheses-in-disguise. But in his early optical papers, Newton’s queries are not hypotheses. In fact, he is building on the method of queries prescribed by Francis Bacon, for whom assembling queries is a specific step in the acquisition and development of natural philosophical knowledge.

To begin, what is Newton’s method of queries? In a letter to Oldenburg, Newton explains that

- “the proper Method for inquiring after the properties of things is to deduce them from Experiments.”

Having obtained a theory in this way, one should proceed as follows: (1) specify queries that suggest experiments that will test the theory; and (2) carry out those experiments.

He then lists eight queries relating to his theory of light and colours, e.g.:

- “4. Whether the colour of any sort of rays apart may be changed by refraction?

“5. Whether colours by coalescing do really change one another to produce a new colour, or produce it by mixing onely?”

He ends the letter, saying:

- “To determin by experiments these & such like Queries which involve the propounded Theory seemes the most proper & direct way to a conclusion. And therefore I could wish all objections were suspended, taken from Hypotheses or any other Heads than these two; Of showing the insufficiency of experiments to determin these Queries or prove any other parts of my Theory, by assigning the flaws & defects in my Conclusions drawn from them; Or of producing other Experiments which directly contradict me, if any such may seem to occur. For if the Experiments, which I urge be defective it cannot be difficult to show the defects, but if valid, then by proving the Theory they must render all other Objections invalid.”

While Newton’s method of queries is experimental, it does not appear to be strictly Baconian. For the Baconian-experimental philosopher, queries serve “to provoke and stimulate further inquiry”. Thus, for the Baconian-experimental philosopher, queries are part of the process of discovery. However, for Newton, queries serve to test the theory and to answer criticisms. Thus, they are part of the process of justification.

Newton uses queries to identify points of difference between his theory and its opponents. For example, in a letter to Hooke he writes:

- “I shall now in the last place proceed to abstract the difficulties involved in Mr Hooks discourse, & without having regard to any Hypothesis consider them in general termes. And they may be reduced to these three Queries. [1] Whether the unequal refractions made without respect to any inequality of incidence, be caused by the different refrangibility of several rays, or by the splitting breaking or dissipating the same ray into diverging parts; [2] Whether there be more then two sorts of colours; & [3] whether whitenesse be a mixture of all colours.”

And in a letter to Huygens, Newton says:

- “Meane time since M. Hu[y]gens seems to allow that white is a composition of two colours at least if not of more; give me leave to rejoyn these Quæres.

“1. Whether the whiteness of the suns light be compounded of the like colours?

“2. Whether the colours that emerg by refracting that light be those component colours separated by the different refrangibility of the rays in which they inhere?”

In both cases, Newton is using queries to steer the debate towards claims that can be tested and resolved by experiment. On both occasions, Newton devotes a considerable amount of space to discussing the experiments that might determine these queries.

These early queries are not hypotheses. Rather, they are empirical questions that may be resolved by experiment. This is not merely a matter of semantics. In the same letter to Hooke, Newton demonstrates this by distinguishing between philosophical queries and hypothetical queries. A philosophical query is one that can be determined by experiment, a hypothetical query cannot. Newton argues that philosophical queries are the only acceptable queries. He equates hypothetical queries with begging the question.

In his later work, Newton’s queries become increasingly speculative, suggesting that they function as de facto hypotheses. Does Newton ultimately reject his early ‘method of queries’?

Next Monday we’ll have a guest post from Greg Dawes on Galileo and the Experimental Philosophy.

Symposium on Experimental Philosophy and the Origins of Empiricism

St Margaret’s College, University of Otago, 18-19 April 2011

Monday 18 April

9.00 Introductory Session (Peter Anstey and Alberto Vanzo)

9.30 Discussion of Peter Anstey, The Origins of the Experimental/Speculative Distinction

Discussant: Gideon Manning

Chair: Alberto Vanzo

11:30 Discussion of Juan Gomez, The Experimental Method and Moral Philosophy in the Scottish Enlightenment

Discussant: Charles Pigden

Chair: Kirsten Walsh

14:30 Discussion of Kirsten Walsh, De Gravitatione and Newton’s Mathematical Method

Discussant: Keith Hutchison

Chair: Philip Catton

20:00 European Panel of Experts (video conference)

Chair: Peter Anstey

Tuesday 19 April

9:30 Discussion of Peter Anstey, Jean Le Rond d’Alembert and the Experimental Philosophy

Discussant: Anik Waldow

Chair: Juan Gomez

11:30 Discussion of Alberto Vanzo, Empiricism vs Rationalism: Kant, Reinhold, and Tennemann

Discussant: Tim Mehigan

Chair: Philip Catton

14:30 Discussion of Alberto Vanzo, Experimental Philosophy in Eighteenth Century Germany

Discussant: Eric Watkins

Chair: Peter Anstey

16:30 Final plenary session, led by Gideon Manning

17:00 Conclusion

Attendance at the symposium is free. However, space is limited, so we advise you to register early. To register and for information, please email peter.anstey@otago.ac.nz.

Abstracts of all papers are available here. If you cannot attend, but would like to read some of the papers, send us an email.