Hip-hop Dunedin: An ethnographic soundscape

A soundscape produced by Biruk Mengstu, for ANTH210 (Translating Culture)

About the soundscape:

My research question was around the influence of Hip-hop on some students in Dunedin. All these sounds were retrieved from the fieldwork (studio apartment and live underground hip hop showcase) and reconstructed to tell a story of the extent of influence hip-hop has on these students.

My research question was around the influence of Hip-hop on some students in Dunedin. All these sounds were retrieved from the fieldwork (studio apartment and live underground hip hop showcase) and reconstructed to tell a story of the extent of influence hip-hop has on these students.

About the ANTH210 process:

Throughout my high school and university life, I have always been interested in the natural science field. However, I have always wanted to learn more about my surroundings and the social science aspect. When I found out about the ANTH210 paper, I thought it would be an excellent opportunity to challenge myself and to get out of my comfort zone as I have never taken an anthropology paper before.

This paper has opened my mind to a different way of thinking and has shown me that there are so many different cultures that are all around which we sometimes don’t realise. This paper has allowed me to get in touch with my creative side, which I never really had the chance to express before. Overall I enjoyed and learned a lot by being a part of the Anthropology 210 (Translating Culture) class.

Contrasting Evils: The raising of the Soviet flag over the Reichstag building

Written by Etienne DeVilliers, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

World War two was one of if not the most costly wars in human history. It has had ongoing significance in global spaces and memory like almost no other event in human history.

The final days of this far-reaching conflict were of particular importance to two groups; the USA and the Soviet Union. In many ways both were trying to present themselves as the hegemonic power of the future [1] with the USA pushing capitalism and the Soviet Union Communism. In particular the “race for Berlin” encapsulates this – with the USA, the French and the British approaching from the western front, and the Soviet Union approaching from the Eastern Front. In many ways, in the closing days of the war the USA were facing two enemies, the remnants of the Axis (in the Japanese and Germans) but also their supposed ally, the Soviet Union [2].

The raising of the Soviet flag over the Reichstag Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raising_a_Flag_over_the_Reichstag#/media/File:Reichstag_flag_original.jpg

An image that encapsulates this complex and nuanced state was the photo of the Raising of the flag of the Soviet Union over the Reichstag building in Berlin in 1945.

Changing meanings, shifting allegiances

The image of the flag on the Reichstag represented different thing to the two hegemonic powers of the USA and the Soviet Union. To the Americans in was a symbol of the raising of a great evil, to the Soviet Union it was a symbol of victory and revenge over an unjust enemy.

The photo itself shows 3 men raising the red flag with the hammer and sickle over the Reichstag surrounded by plumes of smoke. The photographer, Yevgeny Khaldei, stated that he was heavily inspired by the American WWII photograph of the raising of the flag on Iwo Jima, and wished to do something similar. Soviet Union sensitivities meant that Yevgeny Khaldei was not known to be the photographer for many years, the identity of the three men was also unknown until relatively recently.

The imagery present in the photo has shifted meaning drastically over time, as well as having very different meanings within different countries and political alignments.

For the Allies, the Reichstag was in many ways a symbol of their enemy – being in the past the center of German government, the building itself was symbolically constructed to symbolize a unified Germany following its unification in 1871. The Reichstag was covered with statues and images linked to Germany’s mythic past. This highlights the symbolic importance of the Reichstag despite it not being built by the Nazis it reflected much of their ideology. Due to its importance in German history, identity and politics it became a symbol to the allies to – an embodiment of Nazi Germany, and a symbol of what they fought against. This was why the Reichstag was at the center of the Soviet attack on Berlin, despite the fact that it had been a shell of its former self for about 12 years after it was burnt down in 1933.

It was in late April/early May of 1945 that the Reichstag was captured by the ‘red army’ [3]. Many soviet flags were raised on the Reichstag. Out of all the flags raised only one remains in existence today; often referred to as the Victory banner, alluding to the connections of the capturing of the Reichstag and victory within the Soviet mind-set [4]. The victory banner is used at ceremonies commemorating the end of World War 2 and has become of symbol of victory over evil.

Freedom, fascism, and the communist as liberator

Another way that the specific imagery within the photo has be construed by contemporary groups is as a symbol of “Victory over Fascism” by groups such as the international Freedom Battalion (IFB) a far left militant group fighting in places such as Syria against groups such as ISIS [5]. Below is a photograph taken by the IFB in the Syrian city of Raqqa clearly echoing the photo of the Soviet flag on the Reichstag:

The raising of a soviet flag in the Syrian city of Raqqa Source: https://external-preview.redd.it/vFh4-62I3K04F-sgB3qwrxFytHBqY3hK-9BpFYFZbXU.jpg?auto=webp&s=3b37f8dab75a94068502729d08f518d10ae26cbd

To the IFB the photograph represent victory over the evil of facism and as the flag over the Reichstag represented victory over the Nazis the flag in Raqqa to them represents a victory over the Fascism of ISIS [5]. In that regard the Flag raising of the Soviet flag fits into larger trends namely the appeal of experience [7].

This photographic reproduced advances the perception of a continuing tradition of Communists working as liberators. When questioned in regards to the photo these sentiments among IFB members become even clearer “When the red flag flew over Berlin, it was the symbol of victory over nazi-fascism. We consider Raqqa to mean the defeat of Isis-fascism and ourselves to be in the same communist tradition as the liberating troops.”[5]

However, from the perspective of the USA (and many others in the Western block) the image of the communist hammer and sickle on the Reichstag must have seemed an image of two evils: the dying evil of Nazi Germany and the raising evil of the Soviet Union.

We can see this image, showing Soviet Victory over, and the evil it evoked to the Americans, as contributing to the American decision to use the only two nuclear bombs ever used in warfare [2], in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as a display of strength in the face of their greatest rival, the Soviet Union. Yet this act can be interpreted as evil as well.

Contemporary Controversies

As the power of the Nazis waned and the cold war started with the raising of the iron curtain and the division of Berlin the image of the Soviet flag over the Reichstag would have taken on a whole new meaning, a symbol of a race lost…. as well as a symbol of the division of Berlin, and by extension Europe and the world, into the Eastern block and the Western block, separated by an ‘iron curtain’. Thus it was in the wake of the Cold War that the Soviet flag became to many a symbol of evil in a new way.

This can be seen within contemporary spaces where the Soviet flag no longer commands the political power it once did, it still conveys it. To some it represents liberation and equality but to others it still represents the great other of the Cold War as well as a great evil.

An example of the complex space in which the Soviet flag now sits, its raising at the funeral of a man who had been a communist in Stalybridge, in England in 2019 [6]. From the perspectives of the family it was honoring a relative but to the wider population of the town and wider society it was a brought forth feelings of dismay and outrage [7].

The controversial raising of a Soviet flag at a funeral in Salybridge England. Source: https://twitter.com/guidofawkes/status/972131282644856834

The outcry on social media echoed these sentiments within the population as many considered it inappropriate, following a recent suspected Russian involvement in a nerve gas attack on a journalist. This is due to the intrinsic link the Soviet flag has to Russia, and by extension its connection to the suffering inflicted on people by the Russian state.

The ideas surrounding the two evils present in the photograph of the raising of the flag over the Reichstag have not remained static through history. Rather they have be reshaped by time and by space.

In contemporary Russia the photo is a symbol of righteous revenge, and victory over Nazi Germany. For the USA its meaning has shifted, with the raising of the Iron Curtain and the pressures of the Cold War to come, as a former ally became their greatest enemy. A two very different ideologies clashed, for the USA the Flag of the Soviet Union became an evil as great as the evil incapsulated by the Reichstag itself.

References

- Wallerstein, I., 1993. The world-system after the cold war. Journal of Peace Research, 30(1), pp.1-6.

- Sherwin, M.J., 1995. Hiroshima as politics and history. The Journal of American History, 82(3), pp.1085-1093.

- Hicks, J., 2017. A Holy Relic of War: The Soviet Victory Banner as Artefact. Remembering the Second World War, pp.197-216.

- Tony, L.T.M., 2013. Race for the Reichstag: The 1945 Battle for Berlin. Routledge.

- Oak, G. 2018. A red flag over Raqqa. The Morning star retrieved from: https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/red-flag-over-raqqa

- Bugby, T. 2019. Family explains flying of Soviet flag in Stalybridge retrieved from: http://www.stalybridgecorrespondent.co.uk/2018/03/10/family-explains-flying-of-soviet-flag-in-stalybridge/

- Kleinman, A. and Kleinman, J., 1996. The appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times. Daedalus, 125(1), pp.1-23.

Selling Che: the commodification of a communist icon

Written by Jayden Glen, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

Images are powerful. They can inspire fear, love and even sadness. As the common saying goes, ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’. But images can be manipulated out of their original context, and be used to enforce values against their original intention, as shown by the commercial circulation of images of Che Guevara.

Giving Context to the Iconic Image

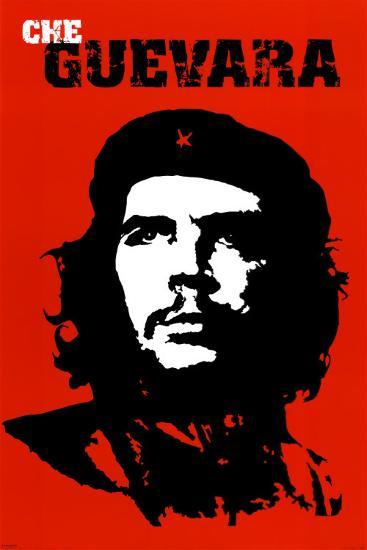

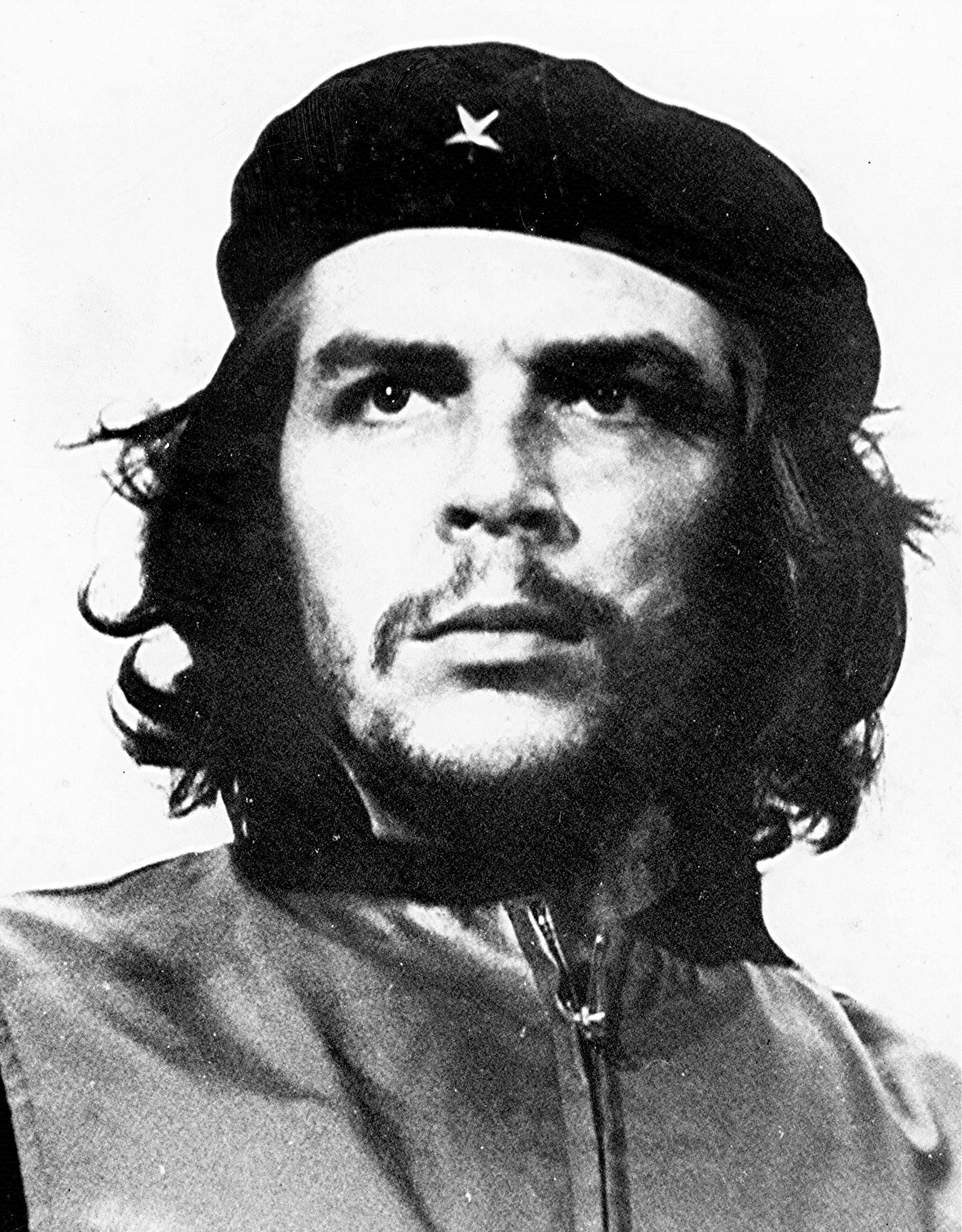

The Guerrillero Heroico or the “Heroic Guerrilla Fighter”, is an iconic photo of Che Guevara, an Argentine Marxist revolutionary from mid 1900’s Cuba.

Guevara fought for communism in Cuba, becoming a strong symbol of the revolution. He remains controversial because of the many extreme measures he took in this fight, despite being widely revered. This iconic picture of him was taken by Alberto Korda on March 5th 1960, during a funeral service for lives lost as a result of the explosion of a munitions freight boat.[1]

The photographer was, at the time, working for the Cuban newspaper Revolución. Koda explained that he was struck by Che Guevara’s powerful expression, a stare over the crowd that showed “absolute implacability”, anger and pain.[1] The newspaper never printed this photo in its coverage of the service, but Koda held on to the portrait in his own studio.[1]

It become “viral” in 1967 when Koda gave two prints to an Italian, who published it for the Cuban government. The photo then began to show up all over the world – particularly in magazines and newspaper, and then in popular culture, such as the colour poster done by Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick.[1]

Che’s later execution in October 1967 cemented his place in history, and this photo in particular would immortalize Che in popular culture too.[1] But I argue that the commercialisation of his image is itself evil, as it goes against the morals that he embodied.

The evil nature of commodifying Che

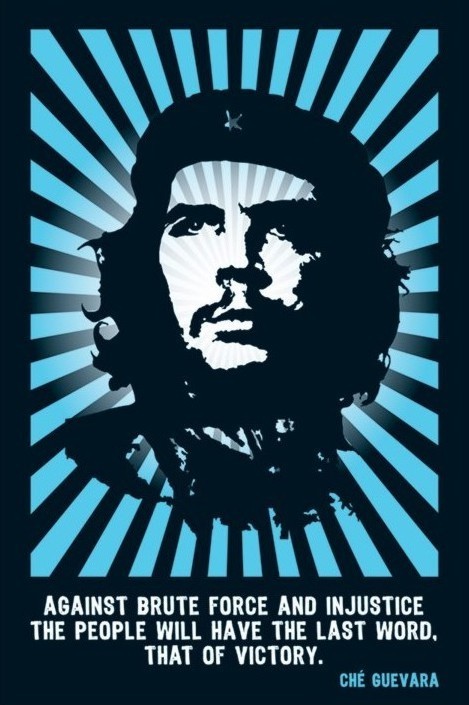

In popular culture Che Guevara’s face has become a symbol for “the power of individual expression”, reinforcing ideas of resistance to conformity and oppression.[2] These ideas resonated with many people and groups at the time, and continue to do so today. In fact, stylised as it often is into a stencil/pop-art look, as a cultural artefact the “Heroic Guerrilla Fighter” has become one of the most popular and marketable images of all time.

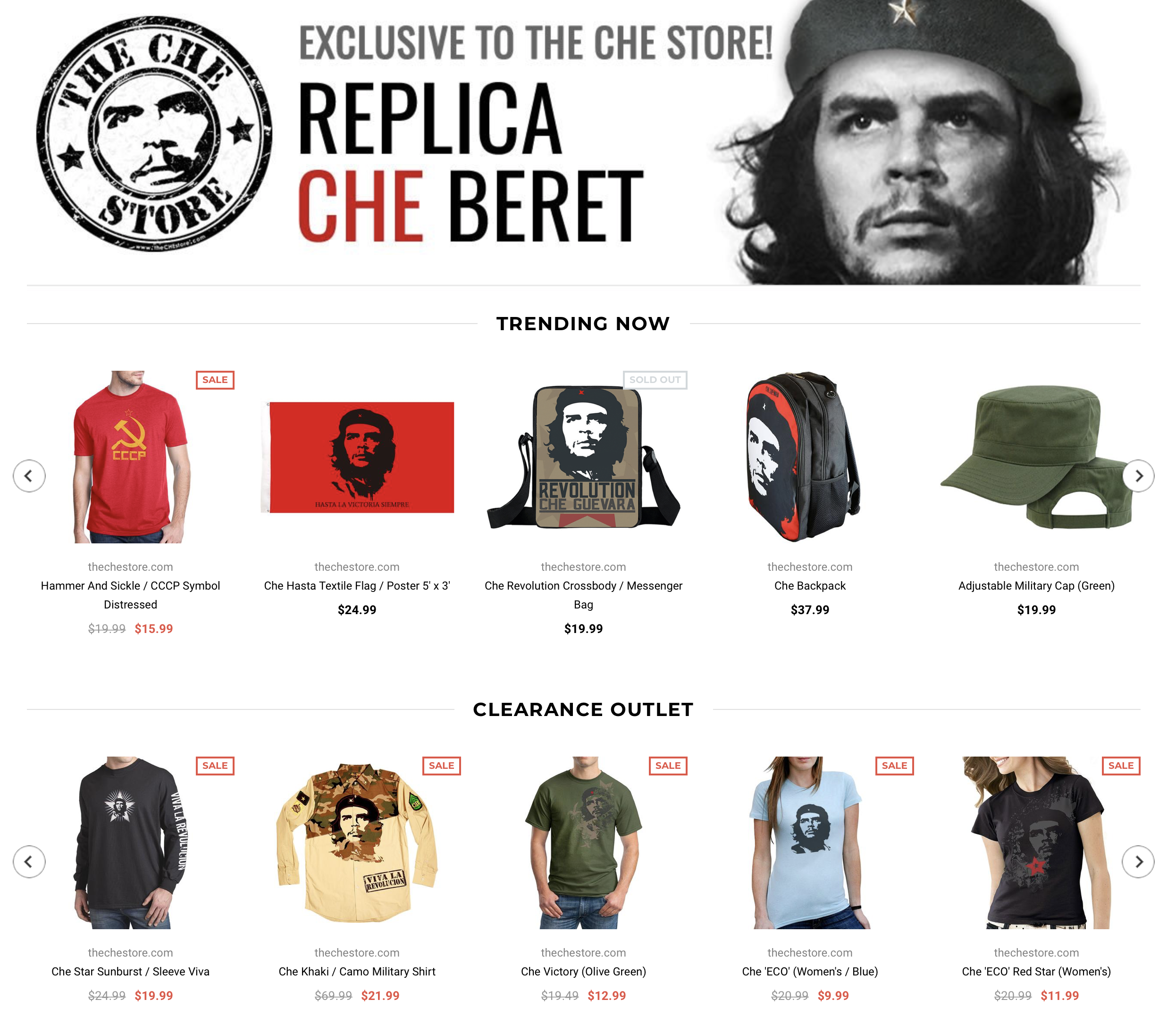

Screenshot of some of the merchandise available from www.thechestore.com, where as we can see Che Guevara’s image and other images of communism being used for profit.

Many (though not all) people may purchase these items because they share a degree of resonance with Che’s political philosophies. But the irony is that “Che would have used the royalties from any such commercial ventures to destroy the social and economic system that produced them”.[2]

The mass consumption of Che’s imagery, I believe, is reflective of what is termed “disordered capitalism”, a term used to describe how aspects of morality and politics are now intertwined with the commercial.[3] This is most observable is in the commodification of suffering, where “experiences of atrocity and abuse” have become highly profitable. This applies to the marketization of Guevara’s image primarily because his global profile occurred after his death – via execution. The significance and viral popularity, implicitly references this.

Che devoted his life to fighting against a capitalist system that in his view was significantly destroying the way of life of poorer people. As well as making money off his martyrdom to this cause, commodification of his image ignores the pain and suffering he endured through his revolutionary campaign while alive, and ignores the suffering of the people he fought for.

From an anthropological lens, this is also a case of global and local systems interacting. The image is consumed by global ‘fans’ and profited on by companies in many other countries. But the sale of his image undermines the political and ideological value that he has as a symbol to Cuban citizens in particular. The commodification of his image shows an attempt to disempower his communistic ideals.

In their analysis of suffering and its representation in media, Kleinman and Kleinman discuss suffering as “one of the existential grounds of human experience”.[3] But in a saturated media age, they argue that North American society has become de-sensitized to images of trauma.[3] Moreover many engagements with the suffering of others, via the media, are as part of a commodified system where cultural capital is gained through the presentation and circulation of trauma stories. So much so that complicated stories are reduced “to a core cultural image of victimization”.[3] Stories like Che Guevara’s become lost in an over saturation of his image, and other images of suffering – removed from context and significance, now bearing cultural and economic capital but losing moral and political potency.

A moral use of images

Frosh’s (2018) work on the way a sense of moral obligations can shape public interactions with stories and images of suffering, can help further unpack the complexities of commodifying and consuming Che Guevara’s image. In his study of Holocaust survivor testimonies, Frosh [4] reinforces that through the production and consumption of these testimonies through digital sites, individuals express and experience a “moral obligation to the past and to the dead”.

Can the same be said of Che Guevara? Should there not be a moral obligation to preserve the mindset and values of this deceased man? If so, should it be via consuming his image as a product, or by refusing to?

There are other reasons of course why this image may be rejected. Che is controversial because while he was viewed by a freedom fighter and hero by Cubans oppressed by the capitalist system of the time, he was also seen as a violent extremist and dictator: in the pursuit of revolution and freedom.

While there are many valid arguments against the man himself as, it is important to stress that even men perceived as evil can generate genuine love and admiration from people. Che is treated with and regarded as a Saint in some parts of the world due to his fight against oppressive and demeaning forces of capitalism – for example in Bolivia, where many worship him as “Saint Ernesto”, or in Cuba, where residents of Havana worship and pray to “Saint Che” by lighting a candle.[5]

As well as obligations to the dead, Frosh talks about obligations to the witness-survivor. In relation to Che Guevara, this could be examined in relation focused toward those that continue to praise and revere Che as a central part of their political ideology, and their real and personal history – in Cuba in particular, but also further afield.[4] This includes those who fought with him and for his cause, and continue to today. It includes intellectuals, workers and students.

We can apply Frosh’s idea to highlight a moral obligation to those living people connected to Che Guevara – those that remember and revere him. Including those Cubans that Che attempted to save as they were belittled and demeaned by an oppressive capitalist system. How would this additional layer of obligation be enacted, in our engagement with this image?

Concluding (and condemning)

Image retrieved from: https: //www.allposters.com/-sp/Che-Guevara-Posters_i1181_.htm accessed 8/4/19

Che Guevara was (and is) a controversial and influential figure. In examining the use of his image I have demonstrated the complexity of moral engagements with iconic political images such as this.

As a man he fought against capitalistic ideals, and has become a cultural icon. As a cultural artefact, his image on merchandise becomes a site of contention considering the moral obligations we not only have to the dead but also the living.

While debate about the evilness of Che the man remains prevalent, I conclude with the assertion that the capitalistic capture of his image for monetary gain is truly evil regardless.

References

[1] Meltzer, S. (2013). The extraordinary story behind the iconic image of Che Guevara and the photographer who took it. [online] Imaging-resource.com. Available at: https://www.imaging-resource.com/news/2013/06/06/the-extraordinary-story-behind-the-iconic-image-of-che-guevara [Accessed 11 Apr. 2019].

[2] McCormick, G. (1997). Che Guevara: The Legacy of a Revolutionary Man. World Policy Journal, [online] 14(4), pp.63-79. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40209557 [Accessed 26 Mar. 2019]. [64]

[3] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996). ‘The appeal of experience; the dismay of images: Cultural appropriations of suffering in our times.’ Daedalus, 125 (1): 1–24. [8; 1; 9; 10]

[4] Frosh, P. (2016) ‘The mouse, the screen and the Holocaust witness: Interface aesthetics and moral response’, New media and society. Sage Publications, 20(1): 351–368 [ pg.353]

[5] Lazo, O. (2016). The Story Behind Che’s Iconic Photo. [online] Smithsonian. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/iconic-photography-che-guevara-alberto-korda-cultural-travel-180960615/ [Accessed 11 Apr. 2019].

The Smell of Suffering: Portrait of a Street Boy

Written by Yi Li, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

Street photographers visualise social suffering through their artwork. They engage (themselves and us) with unfamiliar experiences: shrinking cities, strange portraits. Photographers can function as both moralists and anthropologists. They are often spectators, often self-exiles – presenting a version of evil for others to interpret, but often also fulfilling their own sense of moral obligation.

My argument is that both the positionality of the street photographer, and the medium of the photograph, means that photos sometimes break free from the time and space, conveying a universalism of personal adversity. I use an example of street photography of homeless in Moscow to discuss this.

Down and Out

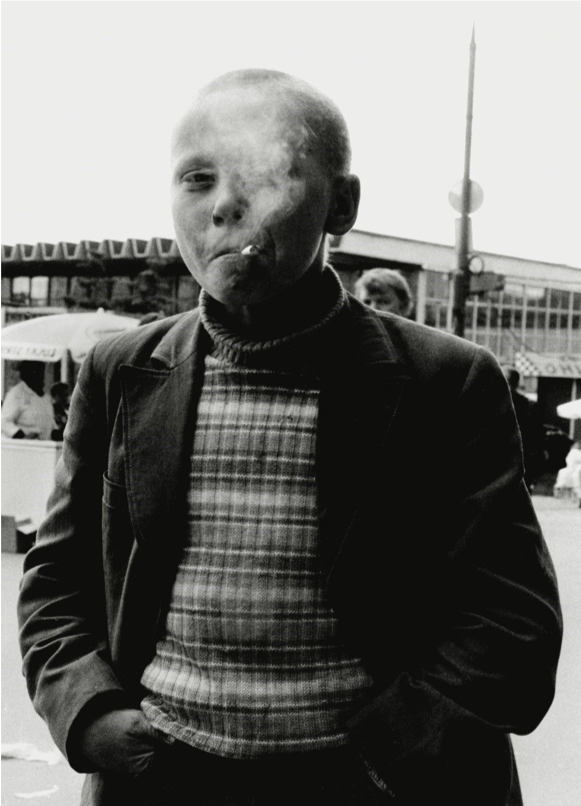

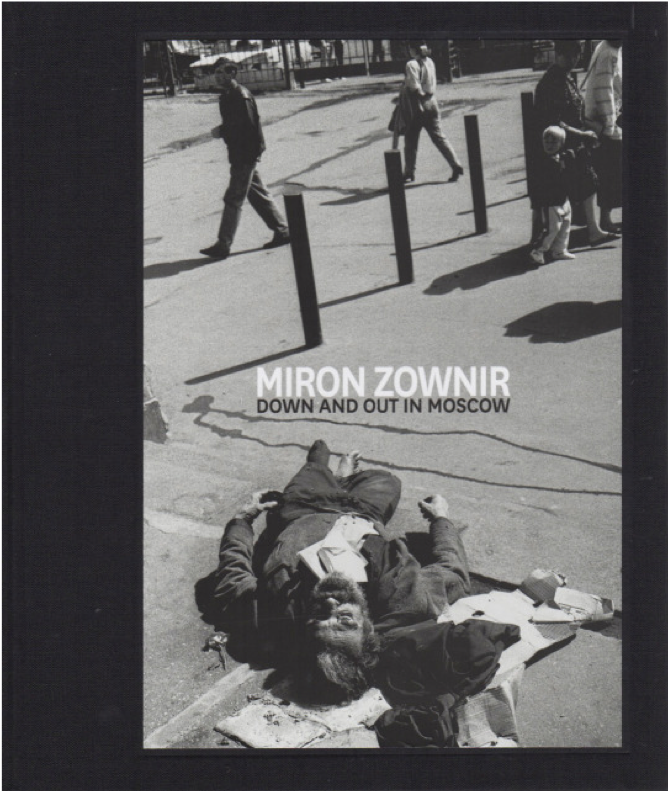

German photographer Miron Zownir is one of the most radical contemporary examples. His focus on marginal characters and the dark side of cities is rooted in his childhood. A Ukrainian-German who grew up in post-war Germany, Zownir as a teenager immersed himself in Eastern European literature without trusting any existing political systems or social stereotypes. His inherent interest in individualists inspired him to live in slum-like places, capturing streets with an anti-establishment attitude.

The street portrait is from Miron Zownir’s publication Down and Out in Moscow, a series of images that captured the homeless crisis in the Russian capital in 1995, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

I noticed the smoking boy with an adult expression to his cynical appearance when I first came across it in 2018. It is somehow different from the other challenging photos in his book. Momentarily, the encounter between Miron Zownir and the boy constructed a story about how individuals were abandoned by society. The diffusing cigarette smoke in front of the boy seems to allow me to smell the evil that permeated the city.

Kleinman & Kleinman (1996)[i] discuss the moral implications of photographs, through contextualising engagements within creators, audiences and images.

Zownir’s photographic experience runs through the technical transition: turning from black-and-white film to digital photography in the post-modern era. This photo was captured in a classic form, of black and white portraiture displayed in gallery spaces, and print journalism (books, and magazines). But it is worth noting that the extended agency of photographs can shift, depending on medium, from a momentary, regional realm to a worldwide standing discussion, through different forms of reprinting and representing.

How different would the viewers experience of this boy’s suffering be, scrolling past a small version in a social media feed? Touching his face on a tablet?

Moral Obligation in Street Photography: Unperceived Suffering as Social Experience

Anthropologists may ask: what is the basis of a photographer’s sense of moral obligation to take photos on streets?

Street photography concentrates on people and their behaviour in public, thereby also recording personal history: though without formal consent, and with the combination of spontaneity, outsider perspective, and private exploration. These subjects of circumstances are generally unaware – either stared at or ignored until they were documented. Street photography uses these collected narratives to define cultures or places, with no duty to serve a larger whole, and no limitation on how they reconstruct these places[ii].

Kleinman & Kleinman considered that photographers represent individual suffering as part of social experience, for others to access – whether these are extreme or ordinary forms of suffering. But as anthropologists, they caution that “there is no timeless or spaceless universal shape to suffering,” (1996, p:2).

In Down and Out in Moscow, Miron Zownir photographed death, sin, and a harsh lived reality. Underlying the powerless state, the rampantly violent proliferation pushed Moscow to become a hotbed of criminal forces in the 1990s; “the most aggressive and dangerous city, … people were dying right there on the street”.[iii] Such tension immediately changed Zownir’s original mission: to document Moscow’s nightlife with three-month project funding from a photographic committee.

Suffering is one of the existential grounds of human experience, and Kleinman & Kleinman suggest that moral witnessing also must involve a sensitivity to others, albeit with unspoken moral and political assumptions. Still functioning as a photographer, Zownir did not tend to query the government, or alter Moscow residents’ condition – but instead chose to live briefly in this shadowed twilight zone, to experience the nightmare.

Individual into the Universal: Reflexive Appreciation against the Silent Oblivion

How can we perceive a stranger’s suffering as universal? Here, a street boy’s sophisticated body language is beyond verbal expressions: dressing in a suit over a horizontal striped turtleneck sweater, his hands are hidden in his pants pockets like a social youth. He looks indifferent to the surroundings and unmoved by the photographer. He is clothed, unlike many beggars, and yet he was banished to a community where no-one had a home.

This portrait reminded me of the 1994 film In the Heat of the Sun. The film is based on Chinese writer Wang Shuo’s novel Wild Beast, which is set in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution, and tells how a teenage boy and his friends are free to roam the streets day and night in a period in which all the social and educational systems are extremely non-functional. Both protagonists are undergoing suffering – the film an example of the way their individual experiences can be abstracted and universalised, for the consumption of a wide variety of audiences. Yet this this also shows us how images and films can provide an insight into personal suffering that is usually invisible – although the harsh realities behind the lives they represent often go on unchanged.

The unwitting suffering of Zownir’s street boy is entangled with the political unrest in Moscow. But as a photograph, it also exists apart from the historical context: “a professional transformation of social life […] a constructed form that ironically naturalised experience.”[iv]

The frame itself cannot communicate this context. Yet it can communicate something else – the universality of human feeling event amidst diverse and ethically incommensurable [v] societies. Perhaps this is the power of portraiture – indeed the seminal psychological research of Ekman, and others, has asserted that emotional expression on faces is universal [vi] – meaning that moods and feelings may at times transcend cultural limitations, an idea often grappled with in the anthropology of emotion.

Conclusion: photography as a container of truth and imagination

Miron Zownir wrote in his poetry: When the earth returns with a thousand sunsets, the truth of the universal is darkness.[vii]

Photography blurs social facts, but seals emotions. Whether the boy would recognise the chaos, ignorance and madness that Zownir’s book communicates, in his free childhood in post-collapse Moscow, cannot be known. Yet seeing this photo as a cultural artefact, we can recognise that both the photographer and the audience as complicit in reproducing and politicising fragmented histories in photography. The photograph becomes a container for these forms of imagination.

Several years later after this photo was taken, when Miron Zownir was back in Moscow for his upcoming exhibition, the city’s exterior had been cleaned up. The silent responses of audiences standing in front of an enlarged version of this photograph, seemed at a vast remove from its original context. What meaning, what comfort, did it hold then? Yet the world still calls for images, as ‘the mixture of moral failures and global commerce is here to stay’ (Kleinman & Kleinman 1996: p. 7).

References:

[i] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[ii] Levy, S. (2019) ‘Street photography as a process’ in Lens Culture Guide to Street Photography, pp. 8-12

[iii] Zownir, M. (2014) ‘I was always an individualist’, Berlin Interviews, by Katerina, http://berlininterviews.com/?p=1375.

[iv] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[v] Fassin, D. (2009) ‘Beyond good and evil?: Questioning the anthropological discomfort with morals.’, Anthropological Theory. Sage, 8(4), pp. 333–344.

[vi] Ekman P, Friesen W (1976). Pictures of Facial Affect. Consulting Psychologists Press : Palo Alto.

[vii] Zownir, M. (2018) ‘Black’, Vision

Fire and Flood: Grounding disaster, trauma, and emotion

I recently read Sociologist Timothy Recuber’s (2016) book, Consuming Catastrophe: Mass Media in America’s Decade of Disaster. It is a great book, and I loved it particularly for acknowledging that media is not just informational, but involves aesthetic and performative cues for emotional response. Recuber draws on case studies of 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina, among others. His writing is specific to the USA and acknowledges its scope as such.

I recently read Sociologist Timothy Recuber’s (2016) book, Consuming Catastrophe: Mass Media in America’s Decade of Disaster. It is a great book, and I loved it particularly for acknowledging that media is not just informational, but involves aesthetic and performative cues for emotional response. Recuber draws on case studies of 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina, among others. His writing is specific to the USA and acknowledges its scope as such.

As an Antipodean social anthropologist, I am struck by the need for a cross-cultural and de-centred lens on these topics. There is space for ethnographic studies that highlight the locally situated nature of disaster and disaster-response – the way the narratives, symbols, words and meanings that make sense of catastrophes around culturally grounded and particular,

Black Saturday: reviewing art on the anniversary of disaster

Last week I attended a talk by Dr. Grace Moore, called ‘The Art of Recovery’. Before moving to Otago’s English Department, Dr Moore worked with the ARC (Australian Research Council) Centre for Excellence for the History of Emotions, her research focussing on fire in Australian historical writing and art. But timing and location meant her response also engaged heavily with the devastating Victorian bushfires of ‘Black Saturday’, in 2009. On this 10-year anniversary of the event, she presented some pieces from a collection of art created by survivors.

Last week I attended a talk by Dr. Grace Moore, called ‘The Art of Recovery’. Before moving to Otago’s English Department, Dr Moore worked with the ARC (Australian Research Council) Centre for Excellence for the History of Emotions, her research focussing on fire in Australian historical writing and art. But timing and location meant her response also engaged heavily with the devastating Victorian bushfires of ‘Black Saturday’, in 2009. On this 10-year anniversary of the event, she presented some pieces from a collection of art created by survivors.

William Strutt’s oil painting ‘Black Thursday’ (1861). Referencing the largest fires ever recorded in Australia, taking place in Victoria 1851.

Dr. Moore’s work makes some fascinating comparisons between this, and 19th century European colonists’ narratives and paintings of bushfire. As such she has been able to highlight some of the moral frameworks and social relationships (i.e. heroism, mateship) that have made sense of bushfires in a culturally-specific way. She notes also that there is a rich tradition of depicting fire among many indigenous Australian communities, which would beg deeper research.

The connection between Moore’s talk and Recuber’s book struck me, in that both addressed representations of disaster (and its aftermath), and also that both discussed the role of emotion and affect as they circulated through particular mediums of communication.

Emotion and trauma: inside, outside, on the page and screen

In Dr. Moore’s talk at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, art was framed as something used to ‘confront’ and ‘work through’ trauma. It is ‘cathartic’, and ‘therapeutic.’ The vested interest in such processes, after trauma, is not entirely individual. Amidst controversy about accountability and the inadequacies of long-term support, Grace noted the investment of local government in programmes that allow people to ‘channel their emotions’.

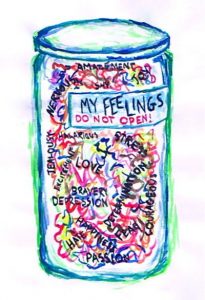

I could also say a lot here, from an anthropological perspective, about the culturally-grounded metaphors of emotion that this all relies on, and in particular the hydraulic metaphors of emotion. These are central to psychodynamic frameworks that emphasise the destructive potential of un-expressed (‘bottled up’) emotions, and the moral and therapeutic values of sharing (‘venting’) emotion.[i]

I could also say a lot here, from an anthropological perspective, about the culturally-grounded metaphors of emotion that this all relies on, and in particular the hydraulic metaphors of emotion. These are central to psychodynamic frameworks that emphasise the destructive potential of un-expressed (‘bottled up’) emotions, and the moral and therapeutic values of sharing (‘venting’) emotion.[i]

I have also written about the distinction between ‘channel’ and ‘vessel’ metaphors of emotion.[ii] In this case I think it is the intersubjectivity of affect that the frequent appearance of ‘channel’ metaphors hint at. They highlight art as not only a personal process but a relational one, a channel for survivors to connect with other people who were not present, across what is often framed as an ineffable void of experience.

Image from the DAX Centre. Source: http://castlemaineart.com/artists/konii-c-burns/konni-c-burns-dax-centre/

Alternatively perhaps the art itself is the vessel, the receptacle, which holds the emotion channelled into it. Indeed Moore noted that emotion and memories are “embedded” into the work. Regional exhibitions focussed on ‘Recording and Collecting Black Saturday’ and the longer-term efforts of DAX Centre to collect these works (and others by victims of broadly-defined ‘trauma’) could be analysed through this lens. It certainly opens up some interesting questions:

- Do these paintings and sculptures represent the materiality of suffering?

- What then, is the political or moral impetus to hold it and preserve it? To communicate it? To view, experience, or consume it?

There is considerable work still to be done examining the ‘moral economy’ of disaster communication: in mass media, and social media. Recuber’s book includes some particularly interesting work on the ‘digital archives’ that formed around the 9/11 and to Hurricane Katrina. It occurs to me that these, and the exhibitions and collections Dr Moore on, can be seen as a deliberate (and ‘high culture’) institutionalisation of the spontaneous shrine that is increasingly a mark of postmodern collective grief.[iii]

Drawing close to the flame: Empathy and its limits

Recuber talks about the ‘aura’ disaster has; the ‘haunting traces of the real’ that it leaves (p16, 26, 90). Are these possible ways to understand the social practice of collecting and preserving ‘trauma’ art?

Recuber’s idea of ‘empathetic hedonism’ also recalls itself here– “in which the desire to understand the suffering of others is pursued doggedly, through always necessarily unsatisfactorily.” (p9).

Recuber notes particular kinds of ‘stylized and idealized’ empathy evoked by mass media coverage of disaster in the contemporary USA (p19). Once again I believe comparative attention to locally situated forms of empathetic engagement in other places would be beneficial. There are undoubtedly some differences, for example, between the capitalist performative merchandise Recuber describes around the Virginia UniTech Shooter, and the patterns of charity, volunteerism, and witnessing/spectatorship specific to Black Saturday.

Stories (including Dr Moore’s own) of watching weather changes in nearby cities create what appears to me to be a distinctive, embodied, and locally-grounded experience of witnessing, mediated by the sight, smell, and taste of smoke.

In examining art made by children’ affected by the Black Saturday bushfires, Moore also poignantly highlighted the way their experience was often mediated by windows – in cars, as they fled, or in schools where they lived with constant view of devastation after the event. Windows featuring in art are indicative of “intensity, shielding, seeing” she points out. This alludes to a bigger question in the communication of catastrophe – the value (and risk) of seeing. Of empathy itself. The question of vicarious traumatisation.

In my own work with youth workers in Canterbury, after the Christchurch quake, metaphors not only of vessels and channels, but also of boundaries, were common in the stories of care, emotional labour, burnout and compassion fatigue I recorded.

Moore’s talk, I noted, included art by one psychologist who counselled survivors of Black Saturday and framed her art around experiences of “emotion oozing red and sad”. The ‘contagion’ model of emotion is heightened when it is extremely traumatic circumstances in question.

Sometimes keeping the channels, the windows, ‘open’ is experienced as dangerous, overwhelming, even when there appears to be a moral imperative to do so. Other times the desire to draw closer to disaster seems to overcome the distance that is safety. But all of these responses occur in situated local worlds – with their own history, their own geography, and their own socio-political contexts, as Recuber and Moore variously highlight.

In emphasising context and comparison, the anthropological lens has value here too. I am eager to see more work that ‘grounds’ disaster, and the communicative practices it generates, in this way.

Written by: Dr Susan Wardell

References:

[i] Lutz, C., White, G.M., 1986. The Anthropology of Emotions. Annual Review of Anthropology 15, 405–436. https://doi.org/10.2307/2155767

[ii] Wardell, S., 2018. Living in the Tension: Care, Selfhood, and Wellbeing Among Faith-based Youth Workers. Carolina Academic Press.

[iii] Magry, P. & Sanchez-Carretero, C. (2007) ‘Memorializing Traumatic Death’, Anthropology Today, 23(3): 1–2.

Women ‘blue’ and bleeding: Witches in contemporary East Indonesia

**Originally published on the ANTH424: Anthropology of evil blog, 22nd June 2018**

Written and visual accounts of witches have changed dramatically across cultures and time. Witches were once described by Europeans in the sixteenth century as old and evil, with wrinkled and deformed features, and are now being depicted in contemporary popular culture as feminist figures who have a pale complexion, and are glamorous and beautiful [1][2]. The visual traits of contemporary witches of East Indonesia are quite distinct from what we encounter in these European historical accounts and in popular culture.

Witches, known as dukun in Indonesia have played a fundamental role in the lives of many East Indonesians, and have impacted how they structure their communities[3]. In this post I analyse how their visual traits and characteristics relate to Mary Douglas’s[4] ideas about the relationship between the body and sociality, purity and pollution. Douglas argues that the body is a symbol of society that requires order and classification, and by referring to East Indonesian witches, one can distinguish this.

In some areas of East Indonesia, there are no distinct visual traits that set apart witches within their communities. Konstantinos Retsikas ethnography [3] concerning sorcery in East Java, Indonesia, noted that both the instigator and the sorcerer remain hidden in fear of being killed. People can only rely on rumours and whispered accusations to identify witches within East Java. As a witch, blending in is the safest approach. At the same time, they share the same motives of envy, greed and jealousy that is common in everyone, challenging people’s ability to accurately recognise the witches within their community.

In some areas of East Indonesia, there are no distinct visual traits that set apart witches within their communities. Konstantinos Retsikas ethnography [3] concerning sorcery in East Java, Indonesia, noted that both the instigator and the sorcerer remain hidden in fear of being killed. People can only rely on rumours and whispered accusations to identify witches within East Java. As a witch, blending in is the safest approach. At the same time, they share the same motives of envy, greed and jealousy that is common in everyone, challenging people’s ability to accurately recognise the witches within their community.

Although due to this lack of distinct visual traits, Retsikas found that in East Java sorcery accusations always tend to focus on one’s relatives, neighbours, friends and work colleagues. Convivial intimacy is risky and choosing one’s friends wisely is critical. Hence, their unidentifiable traits protect some witches, but also leads to uncertainty and moral panic amongst the people of East Java. The unmarked body of witches impacts the communities ability to keep things pure and in order, affecting how members of East Java respond to one another in times of conflict. Thus, this reflects on Douglas’s idea concerning how the body, whether marked or unmarked, is a key symbol in identifying how a community functions.

A key trait prominent in Kodi female hereditary witches from the coastal villages of Sumba is their association with “blue arts” [5].

In Janet Hoskins ethnography, she recognised the transformation of Kodi women into witches led to the appearance of the shade blue in and around their body. As she mentioned, “Hereditary witches have “blueness in them”, they are “bluish people” (tou morongo) whose very blood is believed to be in some way poisonous to others… Blueness is said to be deep inside the liver (ela ate dalo) of a witch, a kind of poison that can affect others even without her willing it” [5]: 322. This poisonous trait is a reflection of pollution and signifies the darkness within hereditary witches. When they are exposed to this powerful trait that can harm the community and their formal structure, it pushes witches into the margins. “Blue arts” or “blueness” found internally and externally in hereditary witches sets them apart from other Kodi women, making them vulnerable to discrimination by their community, and powerful at the same time. Thus, their polluting body has the potential to disrupt the communities social structure and create fear amongst people.

Menstrual blood is a powerful characteristic associated with witchcraft.

Both Konstantinos Retsikas and Janet Hoskins ethnographic study explore the significance of menstrual blood and how the substance has impacted how some villages in East Indonesia function today. In the Huaulu community, Hoskins found that they have strict menstrual taboos to protect their people. Menstruating women are required to stay in menstruating huts away from the men until their cycle has finished. Menstrual blood is believed to be a dangerous and contaminating substance of witches, and can lead to men becoming extremely ill if they come in contact with it. Hence, Huaulu women accept this menstrual taboo as it is seen as a way of protecting the men within their community, and keeps their village pure and clean.

Huaulu strict taboo and the significance of menstrual blood for many other East Indonesian villages relates to Mary Douglas’s idea about the relationship between the body and sociality, purity and pollution. According to Douglas, “The body is a model which can stand for any bounded system”[4]: 115. The bounded system in Huaulu expresses anxiety about the body and its fluids, while at the same time it administers care and protection for the group. Some argue that specific parts of the body, particularly menstrual blood symbolises “dirt [that] offends against order”[4]: 2. Although in Huaulu, their community members are effectively engaging with this polluted and “dirty” substance by creating strict taboos around it, leading to the development of relationships and the strengthening of social order. Therefore, the significance of menstrual blood and its association with witches impacts how Indonesians culturally construct their communities.

Although there are no distinct traits that set apart Indonesian witches in some areas, they continue to play a fundamental role for numerous citizens. Their presence within key substances, and power to cause positive change and conflict within one’s life does not go unnoticed. At the same time, their features relate to Mary Douglas’s ideas of the relationship between the body and sociality, purity and pollution in many ways, affecting how people of East Indonesia function in contemporary society.

Written by: Pulegaomalo Muliagatele-Carter

References:

[1] Briggs 2002: p.15 in Mencej, M. (2007) ‘7- Social Witchcraft: Village Witches’. In: Styrian Witches in European Perspective: Ethnographic Fieldwork, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 313-346.

[2] Buckley, C. (2017) ‘Witches in Popular Culture’. [online]. The Open University. Available from: http://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/literature/witches-popular-culture. [Accessed 14 June 2018].

[3] Retsikas, K. (2010) ‘The Sorcery of Gender: Sex, Death and Difference in East Java, Indonesia’. South East Asia Research, 18(3), pp. 471-502.

[4] Douglas, M. (1966) Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge and K. Paul.

[5] Hoskins, J. (2002) ‘The Menstrual Hut and The Witch’s Lair in Two Eastern Indonesian Societies.’ Ethnology, 41(4), pp. 317-333.

Vaccination debates and the pain of dividuality

**Post originally published on Corpus: conversations about medicine and life, August 7, 2017; with thanks to Sue Wootton for editing and for permission to republish**

Dividuality: “the close proximity and unexpected pull of others in one’s life” (Garish Daswani 2011).

My ears are full of screaming: the name-calling, the CAPS, the exclamation points!!! Whenever vaccination comes up online, and comments are enabled, the conversation quickly devolves into an extremity of outrage and vitriol that reads to me like ‘moral panic.’

My ears are full of screaming: the name-calling, the CAPS, the exclamation points!!! Whenever vaccination comes up online, and comments are enabled, the conversation quickly devolves into an extremity of outrage and vitriol that reads to me like ‘moral panic.’

Coined in the late 1960s, the term ‘moral panic’ makes no judgement on the value of the issues under discussion. Rather, it highlights the social processes in the associated public discourse: the way that story, meaning, and affect coalesce around a particular social problem. Untangling an objective sense of risk from this is nigh on impossible. Besides, people are doing stupid, risky, and harmful things to each other, directly and indirectly, all day long, and in every part of the world. The question becomes not what to think of anti-vaxers, but why the panic about this particular issue, why here, and why now? I believe the answer is not purely medical, but also social and moral.

In matters of morality the contemporary Western world cries ‘choice’ until the word is nearly meaningless. Liberalism snuggles up next to secularism. We fiercely defend our (and others’) rights to make personal decisions, based on personal beliefs. What the issue of vaccination makes horribly clear is the reality is that you can make your personal decisions, based on your personal beliefs, and they can still kill my child. There are limits to our liberalism. Is this the sore spot that the vaccination debate is poking its sordid fingers at? That the personal is social, always.

Arthur Kleinman – psychiatrist, clinician, social anthropologist – discusses morality by looking at “what matters most” or “what is at stake”. In matters of health this includes relationships, personal values and identity. What produces such heat in the debate about vaccine-preventable diseases is that it’s not only individual biographical identities that are threatened, but deeper cultural constructions of the ‘self.’ What the debate specifically grates on is our sense of ourselves as individuals: our clung-to Western vision of the autonomous, bounded, individual self. Silos. Self-governed islands.

Arthur Kleinman – psychiatrist, clinician, social anthropologist – discusses morality by looking at “what matters most” or “what is at stake”. In matters of health this includes relationships, personal values and identity. What produces such heat in the debate about vaccine-preventable diseases is that it’s not only individual biographical identities that are threatened, but deeper cultural constructions of the ‘self.’ What the debate specifically grates on is our sense of ourselves as individuals: our clung-to Western vision of the autonomous, bounded, individual self. Silos. Self-governed islands.

Social anthropologists have compared the different notions of selfhood and personhood that emerge in diverse cultural settings. In many African communities, for example, ethnographic data paints a picture of the self as partible (capable of being divided), and porous (to both physical and spiritual substances) – not ‘individual’, but (according to ethnographers like Girish Daswani) ‘dividual’. This is quite a contrast to the ‘buffered self’ that is a feature of the Western secular age, where the ideal of healthy interpersonal relationships involves having strong interpersonal boundaries.

The vaccination debate invokes a sense of contamination and threat from other human beings. But bodies are never just bodies. They are the site of densely-packed social meanings, and the inspiration for the most accessible and powerful metaphors for pressing existential concerns. Thus the vaccination debate is not only expressive of anxieties about our biological health, but also about our social existence. As each image of an ailing child looms large on our screens, how outrageous it seems to have to acknowledge ourselves as herd animals in this way – how sickening and scary that what matters most to us is at the mercy of those around us. How intolerable. How basically, inescapably, human.

Dividuality cannot just be the folk theory of some cultures… it is the basic reality of all communities. There is an Irish proverb I have always liked:

“In the shadow of each other we must build our lives.”

Though bleak, to me its comfort is in the embrace of that inevitable entanglement with other selves. You will shadow me, just as I will shadow me. I can no sooner extract my life from the influence of others’ dreams, decisions, and faults than I can remove myself from the biological systems of immunity and disease. A relinquishing of the singular pronoun is needed: I, we, are in so many ways collective.

Robyn Maree Pickens’ beautiful essay on bees (published in Turbine/Kapohau 2016) evokes something of this; the sense of ecological interconnectedness which must be cultivated against alarm bells. She concludes by beseeching us to attend to the “nested lives of others.”

Robyn Maree Pickens’ beautiful essay on bees (published in Turbine/Kapohau 2016) evokes something of this; the sense of ecological interconnectedness which must be cultivated against alarm bells. She concludes by beseeching us to attend to the “nested lives of others.”

The air of panic that hovers over the vaccination debate reflects the existential nature of the concerns being expressed: concerns over the threat of vaccine-preventable diseases to the physical wellbeing of our children; threats also to our clung-to visions of ourselves as bounded individuals. We struggle in the grip of an impossible longing for both freedom to make our decisions and freedom from the effects of others’ decisions. Yet this is the shadow-dance we live in. Confronted with a perfect biological metonym for this crumbling dream of moral autonomy, it seems we can do nothing but scream.

Written by: Dr. Susan Wardell

References:

- Cohen, S. (2002). Folk devils and moral panics.

- Daswani, Girish. “(In-)Dividual Pentecostals in Ghana.” Journal of Religion in Africa41, no. 3 (2011): 256–79.

- Kleinman, Arthur. “Caregiving as Moral Experience.” The Lancet 380, no. 9853 (November 9, 2012): 1550–51. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61870-4.

- Pickens, R. M. (2016). We ask so much of them

“I did this, and this is anthropology!”: Interning at a Community Non-Profit

Though many of us who study social anthropology have a keen interest in helping others, from an uncomfortable seat in a crowded lecture hall it can often be difficult to envision how skills being learnt in the classroom might be applicable in a broader setting.

Here postgrad Social Anthropology student Jordan Webb interviews undergrad student Mika Young[1], about their experience participating in the new HUMS301 humanities internship practicum where they had a chance to translate anthropological theory into ‘real’ world practice at a community organisation; Life Matters Suicide Prevention Trust.

Q. Could you briefly explain the humanities internship paper?

A. I guess it’s about applying what you have learnt in class to a practical context. Every student will go out to an organisation in the community and do some sort of project for them, whether it is research or a practical project. Mine happens to be a mix between the two. Since I already have experience working with organisations in the community, I am helping Life Matters Suicide Prevention in creating a new volunteer training programme.

A. I guess it’s about applying what you have learnt in class to a practical context. Every student will go out to an organisation in the community and do some sort of project for them, whether it is research or a practical project. Mine happens to be a mix between the two. Since I already have experience working with organisations in the community, I am helping Life Matters Suicide Prevention in creating a new volunteer training programme.

Q. What initially drew you to this internship opportunity?

A. I often find it difficult to communicate with people about what anthropology can offer outside of research. So I thought because I am already interested in pursuing community work after my degree that this paper would be a good chance to learn how anthropology works in a practical sense. To get some experience in the area, and then be able to communicate to other organisations, this is what I have done and this is how I can help you.

Q. How did you use your anthropology major during your placement?

A. I drew a lot from Wollcot’s ‘3 E’s’ – experiencing, enquiring, and examining[2]. I think it is really useful drawing on your own experience, doing the research to make sure you are well informed, and also talking to people and including their experiences. So for the organisations I researched on behalf of Life Matters, it was important to hear their perspectives on their existing training programmes. That’s how I try to see anthropology, and when I am going into an organisation I make sure I’ve covered these three aspects

Q. There has been a lot of talk in the tertiary teaching community about capstone papers which consolidate entire undergraduate experiences, how does this relate to your experience?

A. I’d say very well in the final semester of my degree. That was another motivating factor as I think it helps to bridge between academic and public world beyond, particularly with anthropology as it can be difficult to communicate what your skills are. It gives you an example of, ‘I did this, and this is anthropology’!

Q. How has this experience helped you to communicate the potential applications of anthropology?

A. It’s still a challenge! I think this also a difficulty discipline wide, translating anthropology for a the general public. But it is definitely nice having this concrete example of how a practical task could be approached from an anthropological perspective. For example, one thing that I was able to offer was approaching other organisations and translating the knowledge they had already developed, in combination with my own volunteer experience, and contributing an anthropological understanding of why this information is important. It helps the organisation as much as it helps me, providing them with a new perspective.

Q. What was your overall impression of the internship and paper?

A. I thought the biggest challenge would be making the paper count toward my anthropology major, but that aspect seems to have been quite seamless. In terms of, workload, the initial groundwork and planning took a lot of time and effort, but after that three week period it became a lot easier to manage my own workload as I became more familiar with the role and the organisation.

Q. Would you recommend the paper to other students?

A. Definitely! I think it is good practice to make those conceptual links between what anthropology is in the classroom and how you can apply that to different situations. I think a lot of students struggle because anthropology is so broad, everything can be anthropology if you want it to be! So the paper helps with developing both anthropological skills and real world skills, and being able to keep an open dialogue with organisations about how anthropology can be used to help them.

A. Anyone can do the internship, but being open to adapting, developing communication, and being willing to learn will all add to the value of the paper and the role. The advice I would give to others would be to find an organisation that suits your interests and experience, and find out what works best for you.

***

Many of us are interested in translating anthropology: imagining how we might be able to benefit our communities once we finally graduate! As Mika has suggested, the humanities internship paper might be one of the ways to help negotiate this transition, and to develop and refine ethnographic skills through sharing their application with others.

As Mika remarked, “The tools we are learning are helpful in an academic context but they are also just life skills! It is challenging finding applied uses for anthropology, but ultimately it is about being human, right?”

[1] Mika Young was also the winner of the 2018 Sites Senior Student Essay Competition.Their winning essay is entitled ‘Tā Moko and the Cultural Politics of Appropriation’, and will be published in the 2018 December issue of Sites.

[2] Wolcott, H.F. (2008). Ethnography: A Way of Seeing. 2nd ed. Blueridge Summit: Altamira Press.

Healing the Self: Motivational Speakers as Shamans

Posted on by smisu13p

Written by: Emma Gamson

[Adapted from an essay written for ANTH228/328: Anthropology of Religion and the Supernatural]

Motivational speaking is a category of verbal performance where the goal is to inspire or motivate an audience 12. Motivational speakers tend to share self-narratives, to convey messages of hope, reassurance and success 8. There is no training or certification required; success depend on an individual speakers’ popularity 8, 9.

Tony Robbins is a highly influential motivational speaker whose messages focus on empowerment, self-transformation and “unleashing the inner-self” 14, 7.

Tony Robbins presents his talk ‘Why We Do What We Do’ at the February 2006 TED conference. The image shows Robbins open and powerful stage presence as he addresses as audience. Source: https://www.ted.com/talks/tony_robbins_asks_why_we_do_what_we_do

This post analyses some of Robbins’ performances, to argue that motivational speaking can be understood as a type of healing practice. I apply concepts from the anthropology of religion, such as liminality, communitas, and ritual, to understand how he frames the self, how he establishes legitimacy, and how he enacts healing.

Narrating your self into (a new) existence

Understandings of the ‘self’ varies cross-culturally. Greek philosophers Plato, and later Descatres, as well as much of early Christian thought, supported a dualist view of the person, in which the body is a physical, mechanical and matter of science, and the mind (in which the person or ‘self’ resides) is non-physical, spiritual and a matter of the church 16, 17. Conversely, Freud, Foucault, Sartre and Social Sciences have supported a non-dualism in which the self is made up of a body and mind immediately connected to each other, and both are subject to the influence of society and power 16. In anthropology, the ‘self’ is typically associated with the perception of one’s own existence, and is different to ‘identity’, which is more related to how ones existence is placed in relation to others 17.

Robbins uses narrative to convey themes of self-renewal, self-help and power of a true inner self, all of which he claims are controlled by state of mind and worldview 2, 15. His key argument is that “you can sculpt the person you want to be with whatever raw material you have available, so long as you acknowledge the early forces that shaped you” 15.

Processes of self are not just about the mind, but about the body too. In anthropology, embodiment theory emphasises the intimate connection between mind, body and culture (in in fact seeks to challenge these as separate categories, all together). Many motivational speakers also take a holistic view, including Tony Robbins, who treats the mind and body as distinct, but directly influencing each other 15.

Religion, ritual, and self-transformation

Ritual practice is a key feature of religion. Rituals can work to express meaning, and apply religious worldviews to daily life 11. Religious worldviews can form the framework against which individuals develop and create their self-narratives. Religious ritual deeply embeds this frameworks through embodied (implicit) and explicit knowledge of one’s self in the context of the world, consequently influencing how one perceives and acts in the world 11.

Tony Robbins on stage at one of his ‘Unleash the Power Within’ seminars. A three-and-a-half-day event oriented towards helping “you unlock and unleash the forces inside you to break through your limitations and take control of your life”. The image is a snapshot showing Robbins enthusiastic and big gestures that are incorporated into his stage performances. Source: https://www.tonyrobbins.com/events/unleash-the-power-within/

As a motivational speaker, Tony Robbins employs embodied, ritualized action in a way similar to religious practice. His talks verbally lay out a worldview in which individuals have an ‘inner power’. Then his rituals make this true by enacting the ‘unleashing’ of this power with bodily action 8, 15, 14.

Specifically, Robbins his audience to participate through verbal agreement 2, 15. Their vocal articulations are a ritual way of unleashing this power. By getting his audience to respond through an embodied ritual of call-and-response, in his talks and seminars, he is asking them to reposition their own self within this worldview; to re-write their self-narrative according to that. In shifting the framework for their story, he shifts the story and thus the self.

Why does ritual work? Hot coals and big crowds

The effectiveness of Robbin’s performance is contingent on his audience. Religion is a dynamic product of human activity that tends to revolve around a central source of legitimacy or authority, but this must be continuously performed, negotiated, reproduced and validated by participants and audience members 1.

A seminar attendee calmly walks across a path of hot coals, embodying the beliefs and ideas that have been taught by Robbins. Behind cheers him on as they people queue for their turn. Source: http://morewealthandhealth.com/tony-robbins-fire-walk-review-read-fire-walk/

Robbins continuously negotiates and reinforces his authority when he prompt action from the audience. For example, Robbins created a ritualized action of walking over hot coals to show the power of the inner self, which many people have attempted 15. The offer would be absurd if the audience did not reinforce and embody support by actually attempting the walk, thus continuing to reinforce and legitimize the authority of Robbins and his worldview.

One key feature in the effectiveness of motivational speaking, is liminality. Anthropologists understand liminality as an intermediary stage in a ‘rite of passage’ ritual, which typically focuses on shifting someone’s social positionality. Like most motivational speakers, Robbins does indeed emphasizes ‘transformation’. We can argue that he uses his events to create a liminal space in which the possibilities for transformation occurs.

Communitas can be experienced in ‘coming of age’ rituals, rock concerts, sports games, prisons, religious events, and more.

The liminal stage is the ‘in between’ stage, and when lots of people are experiencing this together, it can lead to a state called ‘communitas’. Communitas is a state of anti-structure, where usual social boundaries and identities temporarily fall away, and people feel joined by bonds of common feeling 18. Liminality and communitas can both facilitate, acute moments of self-transformation.

Despite the perception of motivational speaking as an ‘individualistic’ form of healing, communitas appears to emerge again in ritualised acts in which Robbins’ audience participants respond collectively, rather than individually 18. After all, would it work the same if we was alone in a room with someone? His seminars can become a space of communitas – the audience all are temporarily separated from their normal lives, and united with others in their intense experiences in that room. It is together that they are remade.

Healing: is Tony Robbins a shaman?

People attending Tony Robbins talks seek empowerment. It is fair to infer then that they come with some sense of deficiency or disempowerment – while their bodies may be healthy, their ‘self’ is in need.

Religion is one framework of meaning that can help individuals make sense of what it means to have or to lose health, what it means to be lacking or whole10. While not a religion, Robbin’s talks similarly offer a framework of meaning that locate the cause of problems, and their solution, within a particular set of symbols and ideas: i.e. about ‘inner power’ and how to ‘unleash it’, and what effects (on both body and mind) this can have.

A shamanic healing ceremony, showing the jhākri (Nepali shaman) alongside a woman undergoing the healing process. Behind is a group who are also participating in and supporting the ritual (Sidkey 2010, p219)

There are similarities in particular with the way Toby Robbins works, and what anthropologists have observed of some shamanic traditions. For example, Yolmo shamans define health by the aesthetics of balance, wholeness and harmony to determine health 4. These values are embodied in the daily life of Yolmo society, embedding them in the body and shaping sensory experiences of health 4, 5. Shamans may conduct rituals involving trance states with vivid imagery to deal with illness such as soul loss 4, 5. This process not only relies on the action of the shaman themselves, but also through the participation of everyone present, including the patient 4, 5. This exemplifies the dynamic relationship between the authority of the religious healer, the participants and the social embodiment of values as key in making sense of the process of healing.

Tony Robbins seems to define health as a unity between how one lives their life and the cultivation of the power of their inner-self to create fulfilment and wellbeing. For example, in a video Robbins guides Rechaud, a 30-year-old man with a stutter, through a ritualized process of searching through memories for a cause of the stutter and bringing out Rechaud’s ‘inner warrior’ 13. Rechaud emerges ‘healed’ from his stutter and delivers a speech at one of Robbins seminars, acting as a symbol of success for this method of healing, which generated intense emotional responses from the crowd 13.

A stock image under the word ‘healing’. Source: pixabay.com

As with the Shamanic trances, Robbins guides Rechaud through a ritualized process of self-narrative that taps into imagery embedded in memories and in the symbol of the self as a ‘warrior’, to transform Rechaud and unify his inner self with his physical body to overcome the stutter.

Conclusion:

Motivational speakers in Anglo-American nations are not unlike shamans in a variety of other cultural settings – they are a culturally sanctioned form of (non-biomedical) healer, with accepted social authority. In observing Tony Robbins’ techniques, we can see how he uses this authority to lead audiences through rituals that facilitate a shift in self. His motivational seminars become a liminal space in which people are taken through a process of re-making their own narratives according to the framework he lays out, and thus are able to heal body, mind, and ‘self’.

References

Posted in Case study, Media/political commentary, Undergrad coursework | Tagged anthropology, authority, communitas, embodiment, healing, health, liminality, motivational speaking, personal growth, religion, Ritual, self, self-narrative, selfhood, shaman, shamanism, Tony Robbins, wellbeing | Leave a reply